This document provides an abstract and table of contents for an MBA thesis that examines how Starbucks integrates corporate social responsibility (CSR) into its business strategy in China. The thesis investigates how CSR has contributed to Starbucks' success in China by analyzing the company using the EFQM CSR framework, value chain analysis, and Porter's Diamond framework. Through a qualitative case study of Starbucks, the research aims to advance understanding of the role of CSR and international culture in the company's China operations.

![Building

a

resource

saving

and

environmentally

friendly

society

is

one

of

the

Chinese

government’s

top

priorities

during

the

current

12th

five-‐year

period.

To

achieve

this,

a

large

range

of

issues

have

been

raised,

including

the

necessity

for

proactively

addressing

climate

change,

resource

conservation

and

management,

developing

a

circular

economy,

promoting

ecological

protection

and

restoration,

improving

water

resources,

and

heightening

disaster

prevention

and

mitigation

systems.

Developing

a

skilled

population

is

also

of

great

significance

to

China.

MNCs

can

respond

to

this

objective

through

personnel

(occupational)

training

and

investment

in

education

through

philanthropic

programs.

China

is

working

to

promote

community

self-‐governance

as

well

as

improving

the

mechanisms

for

safeguarding

people’s

right

(Bu

et

al.,

2013,

p.

54)

2.7

Guanxi.

The

term

Guanxi

refers

to

a

person’s

connections;

in

particular,

to

people

in

influential

or

higher

positions

who

may

be

willing

to

perform

favors

for

you,

with

the

understanding

that

these

favors

will

undoubtedly

be

reciprocated

sometime

in

the

future.

2.8

Mianzi.

Meaning

“face”,

“Mian

Zi”

represents

a

person’s

reputation

and

feelings

of

prestige

(both

real

and

imagined)

within

their

family

unit

and

among

friends,

at

their

workplace

and

in

society.

The

concept

of

“face”

is

be

more

deeply

understood

if

one

recalls

that

China

has

traditionally

been

(and

continues

to

be)

a

highly

hierarchical

society.

The

position

a

Chinese

person

occupies

relative

to

others

is

typically

thought

to

command

a

certain

degree

of

respect

and

requires

certain

types

of

behavior

(Upton-‐McLaughlin,

2013,

p.

1).

2.9

The

Chinese

coffee

market

The

Chinese

consumer

market

for

coffee

is

still

in

the

early

stages

of

maturation.

The

retail

sales

volume

of

coffee

in

China

was

slightly

more

than

30,000

tons

in

2009.

This

translates

to

just

over

0.02

kg

per

capita

per

year.

It

is

China’s

growing

urban

population

of

600

million

people

that

accounts

for

an

estimated

90%

of

coffee

consumption

in

the

country.

This

would

place

annual

per

capita

consumption

by

the

target

consumer

market

at

around

0.05

kg

(International

Trade

center

[ITC],

2010,

p.

8).

For

comparison,

figure

3

shows

the

coffee

consumption

in

other

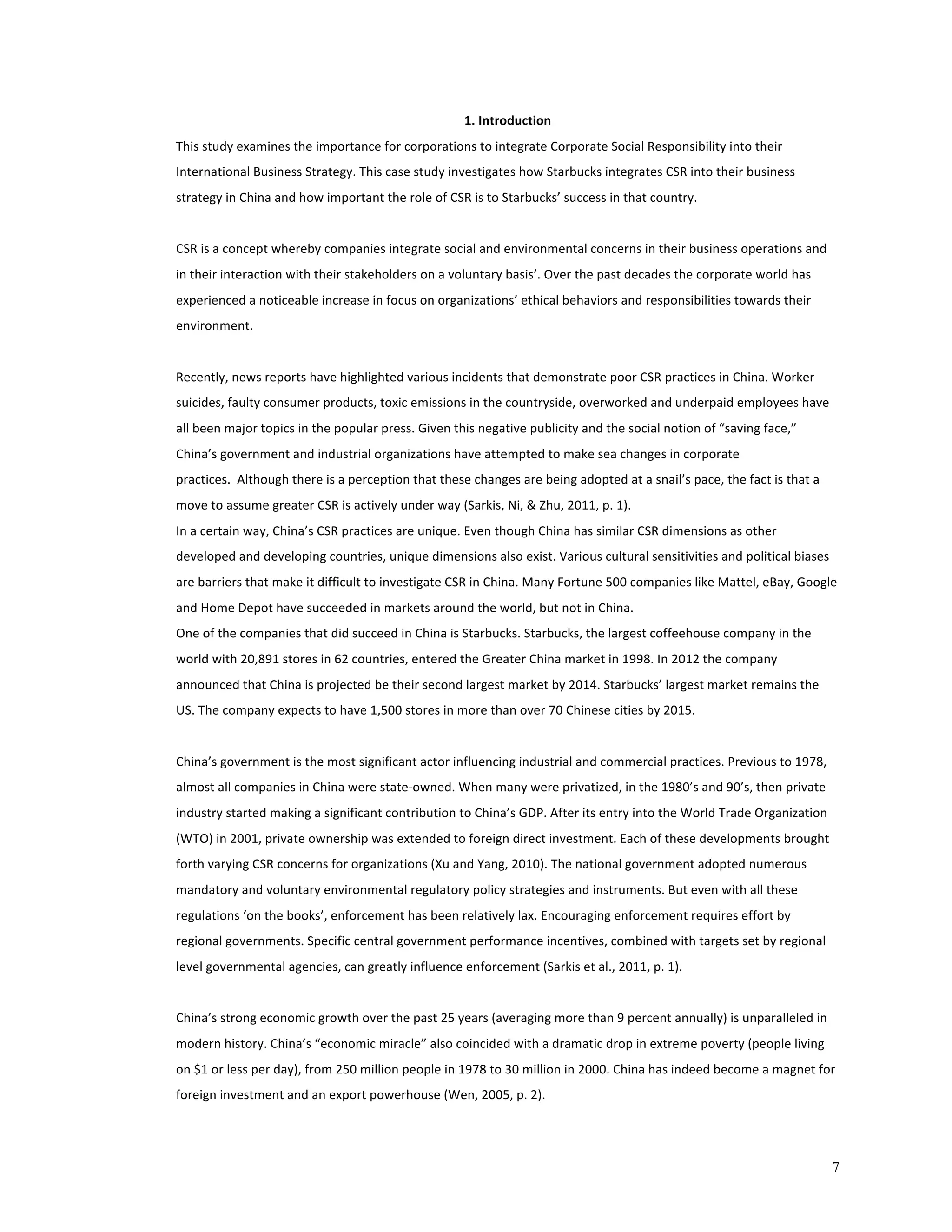

countries.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-21-2048.jpg)

![quality

coffee

that

is

responsibly

grown

and

ethically

traded.

The

cornerstone

of

our

approach

are

the

C.A.F.E.

Practices,

our

comprehensive

coffee-‐buying

program

that

ensures

coffee

quality

while

promoting

social,

economic

and

environmental

standards.”

These

standards

were

developed

in

partnership

with

Conservation

International,

a

Virginia-‐based

nonprofit

that

aims

to

protect

the

earth’s

biodiversity.

Critics

say

that

C.A.F.E.

standards

are

simply

a

set

of

guidelines

co-‐created

and

audited

by

Starbucks

for

larger

coffee

farms.

Starbucks

self-‐auditing

cannot

be

reasonably

considered

as

a

Fair

Trade

means

of

business

certification

when

the

company

operates

on

such

a

global

scale

and

directly

reaps

the

benefits

of

its

auditing

(Rhiannonkate,

2013,

p.

1).

“Unlike

Fair

Trade,

their

standards

do

not

include

a

guaranteed

minimum

price

to

the

producer,”

according

to

Marie-‐Christine

Renard,

a

sociologist

from

the

University

of

Chapingo

in

Mexico

State

(Paley,

2012,

p.

1).

In

2008

Starbucks

made

a

$7.5

million

multi-‐year

commitment

to

CI

and

critics

see

something

unseemly

about

this

deal.

Nonprofit

groups

taking

cash

from

big

companies

are

unlikely

to

push

their

donors

very

hard

(Gunther,

2008,

p.

1).

C.

MacDonald,

the

writer

of

the

book

‘Green

Inc.’

who

worked

for

CI

for

one

year,

accuses

CI

of

green

washing,

(MacDonald,

2008,

p.

89).

Other

critics

argue

that

CI

is

nothing

more

than

a

green

PR

company

and

that

they

should

be

stripped

of

their

UN

NGO

Observer

Status

and

expelled

from

the

various

NGO

caucuses

within

the

UNFCCC

[United

Nations

Framework

Convention

on

Climate

Change]

(Lang,

2011,

p.

1).

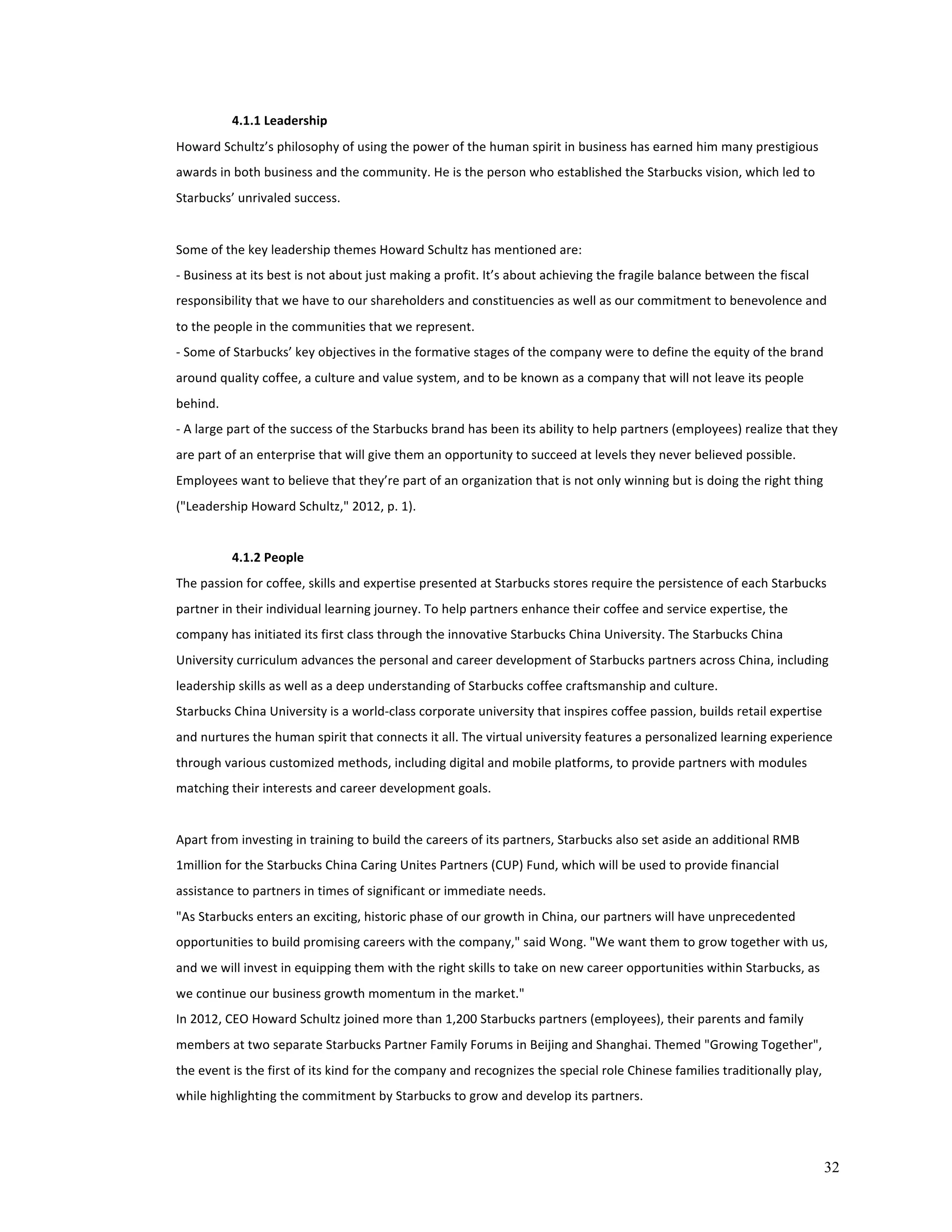

4.3

Porters'

Diamond

Framework

–

looking

outside-‐in.

The

outside-‐in

perspective

is

based

on

the

assumption

that

entrepreneurial

activity

not

only

influences

society

but

that

conversely

social

conditions

also

impact

a

business’s

ability

to

compete.

The

Diamond

Model,

developed

by

Porter,

based

on

the

four

interdependent

areas

of

strategy

and

competition,

production

factors,

supporting

industries,

and

demand

conditions

is

used

to

analyze

the

competitive

environment

for

opportunities

for

CSR

initiatives

("Doing

good

and

deriving

benefit,"

2012).

In

addition

to

understanding

the

social

ramifications

of

the

value

chain,

effective

CSR

requires

an

understanding

of

the

social

dimensions

of

the

company's

competitive

context

-‐

the

"outside-‐in"

linkage

that

affect

its

ability

to

improve

productivity

and

execute

strategy

(Porter

&

Kramer,

2006,

p.

9).

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-45-2048.jpg)

![years

after

Burger

King

first

entered

the

China

market

in

2005,

the

company

has

only

63

restaurants

in

China,

falling

far

short

of

its

own

plan

of

opening

250

to

300

restaurants

by

2012.

According

to

Edelman

partnering

with

NGOs

in

the

APAC

region

brings

credibility

to

CSR,

particularly

if

the

NGO

partner

becomes

an

advocate

for

the

company.

Starbucks

established

partnerships

with

several

Chinese

NGOs.

The

Edelman

Trust

barometer

shows

that

in

China,

where

only

five

years

ago

trust

in

NGO’s

was

48

percent;

today

it

is

81

percent

(Edelman,

2013,

p.

4).

Nonetheless

there

is

criticism.

Critics

say

that

C.A.F.E.

standards,

which

where

developed

in

partnership

with

CI,

a

nonprofit

that

aims

to

protect

the

earth’s

biodiversity,

are

simply

a

set

of

guidelines

co-‐created

and

audited

by

Starbucks

for

larger

coffee

farms.

Moreover

the

reputation

of

CI

is

doubtful,

the

nonprofit

is

accused

of

green

washing

and

critics

argue

that

the

organization

should

be

stripped

of

its

UN

NGO

Observer

Status

and

expelled

from

the

various

NGO

caucuses

within

the

UNFCCC

[United

Nations

Framework

Convention

on

Climate

Change]

(Lang,

2011,

p.

1).

Starbucks

also

has

been

strongly

criticized

by

the

government

for

their

high

prices

and

for

their

lack

of

cultural

sensitivity

on

several

occasions.

The

most

important

criticism

was

having

a

coffee

shop

in

the

Forbidden

City.

A

doubtful

reputation

can

have

significant

consequences

in

China

where

consumers

consider

social

and

environmental

issues

in

major

decisions,

including

where

to

work

(80%)

and

what

to

buy

or

where

to

shop

(83%).

48

What

is

the

role

of

international

culture

to

Starbucks’

success

in

China?

International

culture

is

of

importance

but

adjusting

to

the

local

culture

significantly

contributes

to

Starbucks’

success.

The

company

recognized

that

establishing

and

maintaining

a

global

brand

does

not

mean

having

a

global

platform

or

uniform

global

products.

Starbucks

concentrates

on

finding

the

perfect

balance

of

cultural

integration

and

tradition

for

the

Chinese

market.

Companies

like

Mattel,

eBay,

Google

and

Home

Depot

have

thrived

in

markets

around

the

world,

but

are

not

successful

in

China.

-‐

Why?

-‐

“It’s

a

lack

of

understanding

of

the

legal

and

cultural

environment

that

leads

to

most

failures,”

says

Shawn

Mahoney,

managing

director

of

the

EP

China

consulting

group

(Carlson,

2013,

p.

1).

How

do

China’s

CSR

requirements

influence

Starbucks'

CSR

strategy?

Saving

resources

and

protecting

the

environment

are

top

priorities

for

the

Chinese

government

during

the

current

five-‐year

plan

and

it

has

been

clearly

demonstrated

that

business

entities

with

good

CSR

practice

will

receive

more

support

from

the

authorities

(Bu

et

al.,

2013,

p.

55).

Not

only

the

government

but

also

the

public

demands

social

responsible

behavior.

Ninety

percent

of

Chinese

consumers

use

social

media

to

engage

with

companies

around

critical

issues.

They

are

leveraging

social

channels

to

share

both

positive

(58%)

and

negative

(49%)

information

with

their

networks

(Cone

Communication,

2013,

p.

51).

The

power

of

social

media

was

made

clear

after

the

massive

earthquake

in

Sichuan

in

2008,

which

claimed

the

lives

of

70,000

people

and

left

five

million

homeless.

Shortly

after

the

earthquake

a

list

titled

‘international

iron

rooster’

was

widely

circulated

via

the

Internet.

The

companies

on

that

list

were

accused

of

making

profits

in

China

but](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-50-2048.jpg)

![50

References

Anderlini,

J.

(2013).

China:

Red

restoration.

Retrieved

from

www.cnbc.com

Barford,

V.,

&

Holt,

G.

(2013).

Google,

Amazon,

Starbucks:

The

rise

of

’tax

shaming’.

Retrieved

from

www.bbc.co.uk

Bartiromo,

M.

(2013).

Starbucks’

Schultz

eyes

global

growth.

Retrieved

from

www.usatoday.com

Barton,

D.,

Chen,

Y.,

&

Jin,

A.

(2013).

Mapping

China’s

middle

class.

Retrieved

from

www.mckinsey.com

Bianchi,

P.

(2005).

Corporate

Sustainable

Development.

Retrieved

from

www.eop.org

Brammer,

S.,

Millington,

A.,

&

Rayton,

B.

(2005).

The

contribution

of

corporate

social

responsibility

to

organisational

commitment.

University

of

Bath

School

of

Managemenr

working

paper.

Retrieved

from

www.bath.ac.uk

Branding

in

China

~

The

challenge

of

selling

Starbucks

coffee

in

a

tea-‐drinking

nation

and

other

lessons

.

(2009).

Retrieved

from

www.nzcta.co.nz

Bu,

L.,

Bloomfield,

M.,

&

An,

J.

(2013).

CSR

guide

for

multinational

corporations

in

China.

Retrieved

from

harmony

foundation:

www.harmonyfdn.ca

Burke,

L.,

&

Logsdon,

J.

M.

(1996,

August).

How

corporate

social

responsibility

pays

off,

Long

Range

Planning.

Sciencedirect,

29,

495-‐502.

http://dx.doi.org//10.1016/0024-‐6301(96)00041-‐6

CNBC

Mad

Money.

(2013).

www.cnbc.com

Cambridge

Dictionaries

Online.

(n.d.).

dictionary.cambridge.org

Carlson,

B.

(2013).

Why

big

American

businesses

fail

in

China.

Retrieved

from

www.globalpost.com

Carroll,

A.

B.,

&

Buchholz,

A.

B.

(2001).

Business

and

Society:

Ethics

and

Stakeholders

Management.

:

Cengage

Learning.

Carter,

C.

R.,

&

Jennings,

M.

M.

(2002).

Social

responisibility

and

supply

chain

relationships.

Transport

Research

Part

E,

38,

37-‐52.

Retrieved

from

www.elsevier.com

Chao,

S.

(2012).

A

guide

to

doing

business

in

China

for

Small-‐

and

Medium-‐

Sized

Companies.

[Kindle

DX].

Retrieved

from

www.amazon.com

Chatterjee,

P.,

Purkayasthra,

D.,

&

Indu,

P.

(2009).

Starbucks’

success

story

in

China.

,

BSTR/306,

25.

Retrieved

from

http://www.ecch.com

Chiu,

C.,

Ip,

C.,

&

Silverman,

A.

(2012).

Understanding

social

media

in

China.

Retrieved

from

www.mckinsey.com

Climate

Counts.

(2013).

Methods.

Climate

counts

annual

company

scorecard

report.

Retrieved

from

www.climatecounts.org

Cohen,

E.

(2011,

April

19).

according

to

Starbucks

GRI

Index

[Blog

post].

Retrieved

from

Starbucks

sustainability

reporting

challenges:

csr-‐reporting.blogspot.in

Cone

Communication.

(2013).

Global

CSR

study.

Retrieved

from

cone

communication

website:

www.conecomm.com

Cooke,

J.

A.

(2010).

From

bean

to

cup:

How

Starbucks

transformed

its

supply

chain.

Retrieved

from

www.supplychainquarterly.com

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

(CSR).

(2013).

Retrieved

from

www.wbcsd.org

Craves,

J.

(Ed.).

(2010).

Growing

coffee

in

China.

Retrieved

from

www.coffeehabitat.com

Davis,

J.

(1992).

Ethics

and

evironmental

marketing.

Journal

of

Business

Ethics,

11:2,

81-‐87.

DeVault,

G.

(2012).

Market

Research

Case

Study

-‐

Starbucks’

Entry

into

China.

Retrieved

from

http://marketresearch.about.com

Definition

of

green

washing.

(2014).

Retrieved

from

lexicon.ft.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-52-2048.jpg)

![51

Doing

good

and

deriving

benefit.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.solyp.com

EFQM

Excllence

Model.

(n.d.).

http://www.proveandimprove.org

Edelman.

(2013).

Trust

in

institutions

-‐

NGOs,

media,

government

and

business.

2013

Edelman

Trust

Barometre

executive

summary.

Retrieved

from

www.edelman.com

Fang,

Y.

(2010).

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

in

China:

A

Study

on

corporate

social

responsibility

for

multinational

corporations

in

China

(Doctoral

dissertation,

School

of

Communication

American

University).

Retrieved

from

www.american.edu

Ferdman,

R.

(2013).

Good

morning

China!

Starbucks

will

soon

be

selling

frappuccinos

in

your

grocery

stores.

Retrieved

from

qz.com/84493

Food

services.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

www.climatecounts.org

For

all

the

coffee

in

China.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.economist.com

Fujimori,

F.

(2013,

February

12).

Starbucks’

approach

to

recycle

supply

chain

[Blog

post].

Retrieved

from

Supply

Chain

Management:

cmuscm.blogspot.com

Gasparro,

A.

(2012).

Starbucks:

China

to

Become

No.

2

Market.

Retrieved

from

blogs.wsj.com

Gibson,

D.

T.

(2013).

Can

Coffee

Make

Yunnan

a

Model

for

Chinese

Agricultural

Reform?

Retrieved

from

www.newsecuritybeat.org

Gibson,

D.

T.

(2013).

Exploring

Water-‐Energy-‐Food

Confrontations

in

Southwestern

China.

Retrieved

from

www.wilsoncenter.org

Girrbach,

C.

(2010).

How

Starbucks

took

the

lead

on

LEED.

Retrieved

from

www.greenbiz.com

Global

practices.

(2014).

Retrieved

from

www.edelman.com

Globalization

is

the

international

integration

of

intercultural

ideas,

perspectives,

product/services,

culture,

and

technology.

(n.d.).

Retrieved

from

www.boundless.com

Gossage,

B.

(2011).

Howard

Schultz

on

How

to

Lead

a

Turnaround.

Retrieved

from

www.inc.com

Green,

D.

(2007).

Culture

change

for

sustainable

commercial

buildings.

Retrieved

from

www.yourbuilding.org

Gunther,

M.

(2008).

Corporate

ties

bedevil

green

groups.

Retrieved

from

money.cnn.com

Hamann,

R.,

&

Kapelus,

P.

(2004).

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

in

mining

in

South

Africa:

fair

accountability

or

greenwash?

Society

for

international

development

Local/Global

encounter,

47(3),

85-‐92.

Retrieved

from

www.sidint.org

Harjono,

T.

W.,

&

Marrewijk,

M.

V.

(2001,

).

The

Social

Dimensions

of

BusinessExcellence.

Corporate

environmental

strategy,

8(4),

10.

Hedley,

M.

(2013).

Entering

Chinese

Business-‐to-‐Business

markets:

The

challenges

&

opportunities

.

Retrieved

from

www.b2binternational.com

Hofstede,

G.

(2011).

Dimensionalizing

Cultures:

The

Hofstede

Model

in

Context.

Online

reading

in

psychology

and

culture,

2(1),

26.

http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/2307-‐0919.1014

Hofstede,

G.

(n.d.).

What

about

China?

Retrieved

from

geert-‐hofstede.com

Howard

Schultz

on

Leaderschip.

(2011).

www.youtube.com

International

Trade

center.

(2010).

The

coffee

sector

in

China

-‐

an

overview

of

production,

trade

and

consumption

(SC-‐10-‐188.E).

Retrieved

from

http://goo.gl/6eyLp](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-53-2048.jpg)

![52

Kupke,

S.,

Schneider,

A.,

&

Lattemann,

C.

(2007).

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

and

its

Impact

on

the

Competitiveness

of

Regions.

www.uni-‐potsdam.de,

2.

La

Monica,

P.

R.

(2013).

Is

Howard

Schultz

of

Starbucks

the

best

CEO

ever?

Retrieved

from

buzz.money.cnn.com

Lang,

C.

(2011).

Are

they

any

more

than

a

green

PR

company?

Retrieved

from

www.redd-‐monitor.org

Lara,

A.

N.

(2011).

Starbucks

Cup

Recycling:

What’s

the

Holdup?

Retrieved

from

earth911.com

Legendary

Chinese

judge

has

a

case

against

popular

Starbucks

coffee

mugs.

(2011).

Retrieved

from

english.peopledaily.com.cn

Li-‐Wen,

L.

(2010).

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

in

China:

Window

Dressing

or

Structural

Change.

Berkeley

J.

Int’l

Law,

28(64).

Retrieved

from

scholarship.law.berkeley.edu

Lifestyle

coffee

drinkers

to

keep

demand

growing

in

China.

(2011).

Retrieved

from

chinabevnews.wordpress.com

Lozanova,

S.

(2009).

Starbucks

Coffee:

Green

or

Greenwashed?

Retrieved

from

www.greenbiz.com

MacDonald,

C.

(2008).

Green,

Inc.

Retrieved

from

www.amazon.com

Matten,

D.,

&

Moon,

J.

(2008).

“Implicit”

and

“explicit”

CSR:

A

conceptual

framework

for

a

comparative

understanding

of

corporate

social

responsibility.

Academy

of

management

review,

33(2),

404-‐424.

Retrieved

from

amr.aom.org/content/33/2/404.short

McElhaney,

K.

(2008).

Just

Good

Business:

The

Strategic

Guide

to

Aligning

Corporate

Responsibility

and

Brand.

Retrieved

from

http://www.scribd.com

Mianzi

-‐

how

to

make

&

keep

’Face“

in

China.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

learnchinesebusiness.com

Morrison,

M.

(2013).

McDonald’s

sales

drop

despite

aggressive

discounting.

Retrieved

from

adage.com

Neergard,

P.,

&

Pedersen,

E.

R.

(2012).

The

business

excellence

mdel

got

CSR

implementation?

[journal].

Nang

Yan

Business

Journal,

1

-‐

08,

54.

Retrieved

from

www.hkbs.edu.hk

OSIO.

(2013,

November

16).

China’s

City

Tier

System

[Blog

post].

Retrieved

from

osio-‐china.com

O’Brian,

R.

(2012).

In

China,

Starbucks

balances

global

image,

local

needs:

personal

and

marketing.

Retrieved

from

contextchina.com

Paley,

D.

(2012).

Green

monopolist:

Starbucks

and

Conservation

International

in

Chiapas.

Retrieved

from

wrongkindofgreen.org

Porter,

M.

E.

(1993).

Nationale

Wettbewerbsvorteile,

Erfolgreich

konkurrieren

auf

dem

Weltmarkt.

Austria:

Verlag

Carl

Ueberreuter.

Porter,

M.

E.,

&

Kramer,

M.

R.

(2006,

December).

Strategy

and

society

-‐

the

link

between

competitive

advantage

and

Corporate

Social

Responsibility.

Harvard

Business

Review,

84(12),

1-‐15.

Retrieved

from

http://www.thailca.com

Porter’s

Diamond

of

National

Advantage.

(2010).

Retrieved

from

www.quickmba.com

Q+A

John

Culver.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

www.chinadaily.com.cn

QualityUNE-‐EN

15038,

ISO

9001:2008,

EFQM.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.star-‐spain.com

Rabinovitch,

S.

(2013,

October

21).

Chinese

steam

over

pricey

Starbucks

coffee.

Financial

Times.

Retrieved

from

www.ft.com

Rangan,

V.

K.

(2012).

Why

every

company

needs

a

CSR

strategy

and

how

to

built

it.

Retrieved

from

hbswk.hbs.edu

Rein,

S.

(2012).

Why

Starbucks

Succeeds

in

China

.

Retrieved

from

www.cnbc.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-54-2048.jpg)

![53

Rhiannonkate

(2013).

Starbucks

coffee

company:

a

sustainable

corporation?

Retrieved

from

www.brownbearcafe.com

Riley,

C.

(2013).

China

trouble

deepens

for

Yum

Brands.

Retrieved

from

money.cnn.com

Sarkis,

J.,

Ni,

N.,

&

Zhu,

Q.

(2011).

Winds

of

change:

Corporate

Social

Respnsibility

in

China.

Retrieved

from

iveybusinessjournal.com

Scorecard

Starbucks.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

http://climatecounts.org/searchresults.php?p=term&term=Starbucks

Shao,

H.

(2013).

Critique

Of

Starbucks

By

China’s

State

Broadcaster

Backfires.

Retrieved

from

www.forbes.com

Shobert,

B.

(2013).

Starbucks

China

University:

Learning

the

Culture

of

Service.

Retrieved

from

contextchina.com

Shurtleff,

M.

G.

(1998).

Building

trust.

United

States:

CrispLearing.

Sisco,

C.,

Chorn,

B.,

&

Pruzan-‐Jorgensen,

P.

M.

(2010).

Supply

chain

sustainability

.

A

practical

guide

for

continuous

improvement.

Retrieved

from

www.unglobalcompact.org

Smith,

M.

(2011,

June

1).

Responsibility

Reporting:

A

Glance

at

Starbucks

[Blog

post].

Retrieved

from

Project

CSR:

projectcsr.wordpress.com

Stapledon,

T.

(2012).

Why

infrastructure

sustainability

is

good

for

business.

Retrieved

from

www.wfeo.net

Starbucks.

(2001).

Corporate

Social

Respnsibility

Annual

Report.

Retrieved

from

http://www.starbucks.com/responsibility/global-‐report

Starbucks

CEO

Howard

Schulz.

(2012,

October

19).

Business

model

[Blog

post].

Retrieved

from

http://tanyaoyi.blogspot.com

Starbucks

China.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

www.chinacsrmap.org

Starbucks

Corporation

Fiscal

2012

Annual

Report

[Annual

report

2012].

(2012).

Retrieved

from

investor.starbucks.com

Starbucks

Heads

for

Smaller

China

Cities

as

Coffee

Shops

Triple.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.bloomberg.com

Starbucks

Opens

First

Farmer

Support

Center

in

Yunnan,

China;

Strengthening

Commitment

to

China

Farming

Communities.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.businesswire.com

Starbucks,

Tata

Coffee

open

roasting

plant

in

Karnataka.

(2013).

Retrieved

from

articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com

Starbucks

closes

coffeehouse

in

Beijing’s

Forbidden

City.

(2007).

Retrieved

from

www.nytimes.com

Starbucks

joins

UN

Global

Compact.

(2004).

Retrieved

from

http://www.greenbiz.com

Starbucks

strengthens

commitment

to

China

employment

growth.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

www.fastcasual.com

Tang,

B.

(2012).

Contemporary

Corporate

Social

Responsibility

(CSR)

inChina:

a

case

study

of

a

Chinese

compliant.

Moral

Cents,

1(2),

13-‐22.

Retrieved

from

http://sevenpillarsinstitute.org

Tang,

L.,

&

Li,

H.

(2009,

September).

Corporate

social

responsibility

communication

of

Chinese

and

global

corporations

in

China.

Public

Relation

Review,

35,

199-‐212.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.016

The

pathway

to

be

an

excellent

leader.

(2012).

Retrieved

from

poppycsr.tripod.com

Timeline

-‐

greater

China.

(2010).

Retrieved

from

http://news.starbucks.com

Turker,

D.

(2009).

How

corporate

social

responsibility

influences

organizational

commitment.

Journal

of

Business

Ethics,

89,

189-‐204.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-‐008-‐9993-‐8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-55-2048.jpg)

![54

Turker,

D.

(2009).

Measuring

corporate

social

responsibility:

A

scale

development

study.

Journal

of

Business

Ethics,

85,

411-‐427.

Tyler

Gibson,

D.

(2013).

Sustainable

coffee

growing

in

Yunan.

Retrieved

from

www.wilsoncenter.org

UN

Procurement

Division.

(2004).

http://www.un.org

University

Petru

Maior

Targu

Mures.

(2006).

Studies

and

research

regarding

implemetation

of

CSR

in

organizations.

Retrieved

from

UPM:

www.upm.ro

Upton-‐McLaughlin,

S.

(2013).

Mianzi

-‐

how

to

make

&

keep

’Face’

in

China.

Retrieved

from

learnchinesebusiness.com

Verbeke,

A.

(2009).

International

Business

Strategy

Rethinking

the

Foundations

of

Global

Corporate

Success.

[]..

Retrieved

from

http://tinyurl.com/p6zae6h

Wang,

H.

H.

(2012,

October

8).

Five

things

Starbucks

did

to

get

China

right.

Forbes.

Retrieved

from

www.forbes.com

Wang,

H.

H.

(2013).

How

Burger

King

can

recover

in

China.

Retrieved

from

Wen,

D.

(2005,

December).

China

Copeswith

GlobalizationA

mixed

review.

The

international

forum

on

globalization,

51.

Retrieved

from

www.ifg.org

Wu,

V.

(2012).

Starbucks

in

the

grinder

over

water

use.

Retrieved

from

www.scmp.com

Yang,

Q.,

&

Crowther,

D.

(2012).

The

relationship

between

CSR,

profitability

and

sustainability

in

China.

In

Developments

in

corporate

governance

and

responsibility,

pp.

155-‐175).

[].

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108

Yin,

R.

K.

(2003).

Applications

of

case

study

research

(2nd

ed.).

California:

Sage

Publications.

Zhang,

P.

(2009,

April

1,

2009).

Rethinking

the

impact

of

globalization

and

cultural

identity

in

China.

China

Media

Research.

Retrieved

from

http://www.thelibrary.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesisstarbucks-141105011208-conversion-gate01/75/Integrating-Corporate-Social-Responsibility-into-International-Business-Strategy-56-2048.jpg)