The document serves as a mathematics primer aimed at refreshing essential topics such as calculus, linear algebra, differential equations, and probability & statistics. It defines fundamental mathematical concepts and functions, emphasizing functions' roles in mapping domains to ranges, along with discussions on various types of functions and their properties. Additionally, the document covers limits, exponential and logarithmic functions, and trigonometric functions, illustrating mathematical behaviors and identities.

![(a; b) = a < x < b open interval

[a; b] = a x b closed interval

(a; b] = a < x b semi-open/closed interval

[a; b) = a x < b semi-open/closed interval

So typically we would write x 2 (a; b) :

Examples

1 < x < 1 ( 1; 1)

1 < x b ( 1; b]

a x < 1 [a; 1)

Page 4

1.2 Functions

This is a term we use very loosely, but what is a function? Clearly it is a type of

black box with some input and a corresponding output. As long as the correct

result comes out we usually are not too concerned with what happens ’

inside’

.

A function denoted f (x) of a single variable x is a rule that assigns each ele-

ment of a set X (written x 2 X) to exactly one element y of a set Y (y 2 Y ) :

A function is denoted by the form y = f (x) or x 7! f (x) :

We can also write f : X ! Y; which is saying that f is a mapping such that

all members of the input set X are mapped to elements of the output set Y:

So clearly there are a number of ways to describe the workings of a function.

For example, if f (x) = x3; then f ( 2) = 23 = 8:

Page 5

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

-4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4

We often write y = f (x) where y is the dependent variable and x is the

independent variable.

Page 6

The set X is called the domain of f and the set Y is called the image (or

range), written Domf and Im f; in turn. For a given value of x there should

be at most one value of y. So the role of a function is to operate on the

domain and map it across uniquely to the range.

So we have seen two notations for the same operation.

The …rst y = f (x) suggests a graphical representation whilst the second

f : X ! Y establishes the idea of a mapping.

Page 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-2-320.jpg)

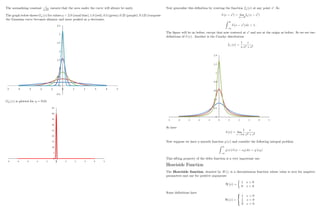

![1.3.2 Trigonometric/Circular Functions

sinx and cosx

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

-8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8

sin x is an odd function, i.e. sin ( x) = sin x:

It is periodic with period 2 : sin (x + 2 ) = sin x. This means that after

every 360 it repeats itself.

sin x = 0 () x = n 8n 2 Z

Page 28

Dom (sin x) =R and Im (sin x) = [ 1; 1]

cos x is an even function, i.e. cos ( x) = cos x:

It is periodic with period 2 : cos (x + 2 ) = cos x.

cos x = 0 () x = (2n + 1) 2 8n 2 Z

Dom (cos x) =R and Im (cos x) = [ 1; 1]

tan x =

sin x

cos x

This is an odd function: tan ( x) = tan x

Periodic: tan (x + ) = tan x

Page 29

Dom = fx : cos x 6= 0g =

n

x : x 6= (2n + 1) 2; n 2 Z

o

= R

n

(2n + 1) 2; n 2 Z

o

Trigonometric Identities:

cos2 x + sin2 x = 1; sin (x y) = sin x cos y cos x sin y

cos (x y) = cos x cos y sin x sin y; tan (x + y) =

tan x + tan y

1 tan x tan y

Exercise: Verify the following sin x + 2 = cos x; cos 2 x = sin x:

The reciprocal trigonometric functions are de…ned by

sec x =

1

cos x

; csc x =

1

sin x

; cot x =

1

tan x

Page 30

More examples on limiting:

lim

x!0

sin x ! 0; lim

x!0

sin x

x

! 1; lim

x!0

jxj ! 0

What about lim

x!0

jxj

x

?

lim

x!0+

jxj

x

= 1

lim

x!0

jxj

x

= 1

therefore

jxj

x

does not tend to a limit as x ! 0:

Page 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![1.6.2 The De…nite Integral

The de…nite integral,

Z b

a

f (x) dx;

is the area under the graph of f (x) ; between x = a and x = b; with

positive values of f (x) giving positive area and negative values of f (x)

contributing negative area. It can be computed if the inde…nite integral is

known. For example

Z 3

1

x3dx =

1

4

x4

3

1

=

1

4

34 14 = 20;

Z 1

1

exdx = [ex]1

1 = e 1=e:

Note that the de…nite integral is also linear in the sense that

Z b

a

(Af (x) + Bg (x)) dx = A

Z b

a

f (x) dx + B

Z b

a

g (x) dx:

Page 80

Note also that a de…nite integral

Z b

a

f (x) dx

does not depend on the variable of integration, x in the above, it only depends

on the function f and the limits of integration (a and b in this case); the

area under a curve does not depend on what we choose to call the horizontal

axis.

So

Z b

a

f (x) dx =

Z b

a

f (y) dy =

Z b

a

f (z) dz:

We should never confuse the variable of integration with the limits of integra-

tion; a de…nite integral of the form

Z x

a

f (x) dx;

use dummy variable.

Page 81

If a < b < c then

Z c

a

f (x) dx =

Z b

a

f (x) dx +

Z c

b

f (x) dx:

Also

Z a

c

f (x) dx =

Z c

a

f (x) dx:

Page 82

1.6.3 Integration by Substitution

This involves the change of variable and used to evaluate integrals of the form

Z

g (f (x)) f0 (x) dx;

and can be evaluated by writing z = f (x) so that dz=dx = f0 (x) or

dz = f0 (x) dx: Then the integral becomes

Z

g (z) dz:

Examples:

Z

x

1 + x2

dx : z = 1 + x2 ! dz = 2xdx

Z

x

1 + x2

dx =

1

2

log (z) + C =

1

2

log 1 + x2 + C

= log

q

1 + x2 + C

Page 83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-21-320.jpg)

![R

xe x2

dx : z = x2 ! dz = 2xdx

Z

xe x2

dx =

1

2

Z

ezdz

=

1

2

ez + C =

1

2

e x2

+ C

Z

1

x

log (x) dx =

Z

z dz =

1

2

z2 + C

=

1

2

(log (x))2

+ C

with z = log (x) so dz = dx=x and

Z

ex+ex

dx =

Z

exeex

dx =

Z

ezdz

= ez + C = eex

+ C

with z = ex so dz = exdx:

Page 84

The method can be used for de…nite integrals too. In this case it is usually more

convenient to change the limits of integration at the same time as changing

the variable; this is not strictly necessary, but it can save a lot of time.

For example, consider

Z 2

1

ex2

2xdx:

Write z = x2; so dz = 2xdx: Now consider the limits of integration; when

x = 2; z = x2 = 4 and when x = 1; z = x2 = 1: Thus

Z x=2

x=1

ex2

2xdx =

Z z=4

z=1

ezdz

= [ez]z=4

z=1 = e4 e1:

Page 85

Further examples: consider

Z x=2

x=1

2xdx

1 + x2

:

In this case we could write z = 1 + x2; so dz = 2xdx and x = 1

corresponds to z = 2, x = 2 corresponds to z = 5; and

Z x=2

x=1

2x

1 + x2

dx =

Z z=5

z=2

dz

z

= [ln (z)]z=5

z=2 = log (5) ln (2)

= ln (5=2)

We can solve the same problem without change of limit, i.e.

n

ln 1 + x2

ox=2

x=1

! ln 5 ln 2 = ln 5=2:

Page 86

Or consider

Z x=e

x=1

2

log (x)

x

dx

in which case we should choose z = log (x) so dz = dx=x and x = 1

gives z = 0; x = e gives z = 1 and so

Z x=e

x=1

2

log (x)

x

dx =

Z z=1

z=0

2zdz =

h

z2

iz=1

z=0

= 1:

Page 87](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![the …rst non-zero entry of each row increases row by row.

A matrix A is said to be row equivalent to a matrix B; written A B

if B can be obtained from A from a …nite sequence of operations called

elementary row operations of the form:

[ER1]: Interchange the i th and j th rows: Ri $ Rj

[ER2]:Replace the i th row by itself multiplied by a non-zero constant k :

Ri ! kRi

[ER3]:Replace the i th row by itself plus k times the j th row: Ri ! Ri+kRj

These have no a¤ect on the solution of the of the linear system which gives

the augmented matrix.

Page 152

Examples:

Solve the following linear systems

1.

2x + y 2z = 10

3x + 2y + 2z = 1

5x + 4y + 3z = 4

9

>

=

>

;

Ax = b with

A =

0

B

@

2 1 2

3 2 2

5 4 3

1

C

A and b =

0

B

@

10

1

4

1

C

A

The augmented matrix for this system is

0

B

@

2 1 2

3 2 2

5 4 3

10

1

4

1

C

A

R2!2R2 3R1

R3!2R3 5R1

0

B

@

2 1 2

0 1 10

0 3 16

10

28

42

1

C

A

Page 153

R3!R3 3R2

R1!R1 R2

0

B

@

2 0 12

0 1 10

0 0 14

38

28

42

1

C

A

14z = 42 ! z = 3

y + 10z = 28 ! y = 28 + 30 = 2

x 6z = 19 ! x = 19 18 = 1

Therefore solution is unique with

x =

0

B

@

1

2

3

1

C

A

Page 154

2.

x + 2y 3z = 6

2x y + 4z = 2

4x + 3y 2z = 14

9

>

=

>

;

0

B

@

1 2 3

2 1 4

4 3 2

6

2

14

1

C

A

R2!R2 2R1

R3!R3 4R1

0

B

@

1 2 3

0 5 10

0 5 10

6

10

10

1

C

A

R3!R3 R2

R2!0:5R2

0

B

@

1 2 3

0 1 2

0 0 0

6

2

0

1

C

A

Number of equations is less than number of unknowns.

y 2z = 2 so z = a is a free variable) y = 2 (1 + a)

x + 2y 3z = 6 ! x = 6 2y + 3z = 2 a

Page 155](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-39-320.jpg)

![( 1)1+1

A11 jM11j + ( 1)1+2

A12 jM12j + ( 1)1+3

A13 jM13j

= 1

2 1

1 3

1

1 1

0 3

+ 0

1 2

0 1

= (2 3 1 1) (1 3 1 0) + 0 = 5 3

= 2

Here we have expanded about the 1st row - we can do this about any row. If

we expand about the 2nd row - we should still get jAj = 2:

We now calculate the adjoint:

( 1)1+1

M11 = +

2 1

1 3

( 1)1+2

M12 =

1 1

0 3

( 1)1+3

M13 = +

1 2

0 1

( 1)2+1

M21 =

1 0

1 3

( 1)2+2

M22 = +

1 0

0 3

( 1)2+3

M23 =

1 1

0 1

( 1)3+1

M31 = +

1 0

2 1

( 1)3+2

M32 =

1 0

1 1

( 1)3+3

M33 = +

1 1

1 2

Page 160

adj A =

0

B

@

5 3 1

3 3 1

1 1 1

1

C

A

T

We can now write the inverse of A (which is symmetric)

A 1 =

1

2

0

B

@

5 3 1

3 3 1

1 1 1

1

C

A

Elementary row operations (as mentioned above) can be used to simplify a

determinant, as increased numbers of zero entries present, requires less calcu-

lation. There are two important points, however. Suppose the value of the

determinant is jAj ; then:

[ER1]: Ri $ Rj ) jAj ! jAj

[ER2]: Ri ! kRi ) jAj ! k jAj

Page 161

2.5 Orthogonal Matrices

A matrix P is orthogonal if

PPT = PTP =I:

This means that the rows and columns of P are orthogonal and have unit

length. It also means that

P 1 = PT:

In two dimensions, orthogonal matrices have the form

cos sin

sin cos

!

or

cos sin

sin cos

!

for some angle and they correspond to rotations or re‡ections.

Page 162

So rows and columns being orthogonal means row i row j = 0; i.e. they are

perpendicular to each other.

(cos ; sin ) ( sin ; cos ) =

cos sin + sin cos = 0

(cos ; sin ) (sin ; cos ) =

cos sin sin cos = 0

v = (cos ; sin )T

! jvj = cos2 + ( sin )2

= 1

Finally, if P =

cos sin

sin cos

!

then

P 1 =

1

cos2 sin2

| {z }

=1

cos sin

sin cos

!

= PT :

Page 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-41-320.jpg)

![Hence K = 1

30 (1 i) to give

yp =

1

30

Re (1 i) (cos 3x + i sin 3x)

=

1

30

(cos 3x + i sin 3x i cos 3x + sin 3x)

so general solution becomes

y = e x + e6x 1

30

(cos 3x + sin 3x)

Page 220

3.5.1 Failure Case

Consider the DE y00 5y0 + 6y = e2x, which has a CF given by y (x) =

e2x + e3x. To …nd a PI, if we try yp = Ae2x, we have upon substitution

Ae2x [4 10 + 6] = e2x

so when k (= 2) is also a solution of the C.F , then the trial solution yp =

Aekx fails, so we must seek the existence of an alternative solution.

Page 221

Ly = y00 + ay0 + b = ekx - trial function is normally yp = Cekx:

If k is a root of the A.E then L Cekx = 0 so this substitution does not

work. In this case, we try yp = Cxekx - so ’

go one up’

.

This works provided k is not a repeated root of the A.E, if so try yp = Cx2ekx,

and so forth ....

Page 222

3.6 Linear ODE’

s with Variable Coe¢ cients - Euler Equa-

tion

In the previous sections we have looked at various second order DE’

s with

constant coe¢ cients. We now introduce a 2nd order equation in which the

coe¢ cients are variable in x. An equation of the form

L y = ax2d2y

dx2

+ x

dy

dx

+ cy = g (x)

is called a Cauchy-Euler equation. Note the relationship between the coe¢ cient

and corresponding derivative term, ie an (x) = axn and

d ny

dxn

, i.e. both power

and order of derivative are n.

Page 223](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-56-320.jpg)

![The equation is still linear. To solve the homogeneous part, we look for a

solution of the form

y = x

So y0 = x 1 ! y00 = ( 1) x 2 , which upon substitution yields the

quadratic, A.E.

a 2 + b + c = 0

[where b = ( a)] which can be solved in the usual way - there are 3 cases

to consider, depending upon the nature of b2 4ac.

Page 224

Case 1: b2 4ac > 0 ! 1, 2 2 R - 2 real distinct roots

GS y = Ax 1 + Bx 2

Case 2: b2 4ac = 0 ! = 1 = 2 2 R - 1 real (double fold) root

GS y = x (A + B ln x)

Case 3: b2 4ac < 0 ! = i 2 C - pair of complex conjugate

roots

GS y = x (A cos ( ln x) + B sin ( ln x))

Page 225

Example 1 Solve x2y00 2xy0 4y = 0

Put y = x ) y0 = x 1 ) y00 = ( 1) x 2 and substitute

in DE to obtain (upon simpli…cation) the A.E. 2 3 4 = 0 !

( 4) ( + 1) = 0

) = 4 & 1 : 2 distinct R roots. So GS is

y (x) = Ax4 + Bx 1

Example 2 Solve x2y00 7xy0 + 16y = 0

So assume y = x

A.E 2 8 + 16 = 0 ) = 4 , 4 (2 fold root)

’

go up one’

, i.e. instead of y = x , take y = x ln x to give

y (x) = x4 (A + B ln x)

Page 226

Example 3 Solve x2y00 3xy0 + 13y = 0

Assume existence of solution of the form y = x

A.E becomes 2 4 + 13 = 0 ! =

4

p

16 52

2

=

4 6i

2

1 = 2 + 3i, 2 = 2 3i i ( = 2, = 3)

y = x2 (A cos (3 ln x) + B sin (3 ln x))

Page 227](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-57-320.jpg)

![1.7 Probability Distributions 1 PROBABILITY

a) Find k and Sketch the probability distribution

b) Find P(X ≤ 1.5)

a)

Z +∞

∞

f(x)dx = 1

1 =

Z 2

1

kdx +

Z 4

2

k(x − 1)dx

1 = [kx]2

1 +

kx2

2

− kx

4

2

1 = 2k − k + [(8k − 4k) − (2k − 2k)]

1 = 5k

∴ k =

1

5

19

1.8 Cumulative Distribution Function 1 PROBABILITY

b)

P(X ≤ 1.5) =

Z 1.5

1

1

5

dx

=

hx

5

i1.5

1

=

1

10

1.8 Cumulative Distribution Function

The CDF is an alternative function for summarising a

probability distribution. It provides a formula for P(X ≤

x), i.e.

F(x) = P(X ≤ x)

1.8.1 Discrete Random variables

Example

Consider the probability distribution

x 1 2 3 4 5 6

P(X = x) 1

2

1

4

1

8

1

16

1

32

1

32

F(X) = P(X ≤ x)

Find:

a) F(2) and

b) F(4.5)

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-70-320.jpg)

![1.9 Expectation and Variance 1 PROBABILITY

For a discrete random variable

V ar(X) = E(X2

) − [E(X)]2

Now, for previous example

E(X2

) = 12

×

1

2

+ 22

×

1

4

+ 32

× 18 + 42

×

1

8

E(X) =

15

18

∴ V ar(X) =

71

64

= 1.10937...

Standard Deviation = 1.05(3s.f)

1.9.2 Continuous Random Variables

For a continuous random variable

E(X) =

Z

allx

xf(x)dx

and

V ar(X) = E(X2

) − [E(X)]2

=

Z

allx

x2

f(x)dx −

Z

allx

xf(x)dx

2

Example

if

f(x) =

3

32(4x − x2

) 0 ≤ x ≤ 4

0 otherwise

27

1.9 Expectation and Variance 1 PROBABILITY

Find E(X) and V ar(X)

E(X) =

Z 4

0

x.

3

32

(4x − x2

)dx

=

3

32

Z 4

0

4x − x2

dx

=

3

32

4x3

3

−

x4

4

4

0

=

3

32

4(4)3

3

−

44

4

− (0)

= 2

V ar(X) = E(X2

) − [E(X)]2

=

Z 4

0

x2

.

3

32

(4x − x2

)dx − 22

=

3

32

4x4

4

−

x5

5

4

0

− 4

=

3

32

44

−

45

5

− 4

=

4

5

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-74-320.jpg)

![1.10 Expectation Algebra 1 PROBABILITY

1.10 Expectation Algebra

Suppose X and Y are random variables and a,b and c

are constants. Then:

• E(X + a) = E(X) + a

• E(aX) = aE(X)

• E(X + Y ) = E(X) + E(Y )

• V ar(X + a) = V ar(X)

• V ar(aX) = a2

V ar(X)

• V ar(b) = 0

If X and Y are independent, then

• E(XY ) = E(X)E(Y )

• V ar(X + Y ) = V ar(X) + V ar(Y )

29

1.11 Moments 1 PROBABILITY

1.11 Moments

The first moment is E(X) = µ

The nth

moment is E(Xn

) =

R

allx xn

f(x)dx

We are often interested in the moments about the

mean, i.e. central moments.

The 2nd

central moment about the mean is called the

variance E[(X − µ)2

] = σ2

The 3rd

central moment is E[(X − µ)3

]

So we can compare with other distributions, we scale

with σ3

and define Skewness.

Skewness =

E[(X − µ)3

]

σ3

This is a measure of asymmetry of a distribution. A

distribution which is symmetric has skew of 0. Negative

values of the skewness indicate data that are skewed to

the left, where positive values of skewness indicate data

skewed to the right.

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-75-320.jpg)

![1.11 Moments 1 PROBABILITY

The 4th

normalised central moment is called Kurtosis

and is defined as

Kurtosis =

E[(X − µ)4

]

σ4

A normal random variable has Kurtosis of 3 irrespec-

tive of its mean and standard deviation. Often when

comparing a distribution to the normal distribution, the

measure of excess Kurtosis is used, i.e. Kurtosis of

distribution −3.

Intiution to help understand Kurtosis

Consider the following data and the effect on the Kur-

tosis of a continuous distribution.

xi µ ± σ :

The contribution to the Kurtosis from all data points

within 1 standard deviation from the mean is low since

(xi − µ)4

σ4

1

e.g consider

x1 = µ +

1

2

σ

then

(x1 − µ)4

σ4

=

1

2

4

σ4

σ4

=

1

2

4

=

1

16

xi µ ± σ :

31

1.11 Moments 1 PROBABILITY

The contribution to the Kurtosis from data points

greater than 1 standard deviation from the mean will

be greater the further they are from the mean.

(xi − µ)4

σ4

1

e.g consider

x1 = µ + 3σ

then

(x1 − µ)4

σ4

=

(3σ)4

σ4

= 81

This shows that a data point 3 standard deviations

from the mean would have a much greater effect on the

Kurtosis than data close to the mean value. Therefore,

if the distribution has more data in the tails, i.e. fat tails

then it will have a larger Kurtosis.

Thus Kurtosis is often seen as a measure of how ’fat’

the tails of a distribution are.

If a random variable has Kurtosis greater than 3 is

is called Leptokurtic, if is has Kurtosis less than 3 it is

called platykurtic

Leptokurtic is associated with PDF’s that are simul-

taneously peaked and have fat tails.

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-76-320.jpg)

![1.11 Moments 1 PROBABILITY

33

1.12 Covariance 1 PROBABILITY

1.12 Covariance

The covariance is useful in studying the statistical de-

pendence between two random variables. If X and Y

are random variables, then theor covariance is defined

as:

Cov(X, Y ) = E [(X − E(X))(Y − E(Y ))]

= E(XY ) − E(X)E(Y )

Intuition

Imagine we have a single sample of X and Y, so that:

X = 1, E(X) = 0

Y = 3, E(Y ) = 4

Now

X − E(X) = 1

and

Y − E(Y ) = −1

i.e.

Cov(X, Y ) = −1

So in this sample when X was above its expected value

and Y was below its expected value we get a negative

number.

Now if we do this for every X and Y and average

this product, we should find the Covariance is negative.

What about if:

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-77-320.jpg)

![2 STATISTICS

2 Statistics

2.1 Sampling

So far we have been dealing with populations, however

sometimes the population is too large to be able to anal-

yse and we need to use a sample in order to estimate the

population parameters, i.e. mean and variance.

Consider a population of N data points and a sample

taken from this population of n data points.

We know that the mean and variance of a population

are given by:

population mean, µ =

PN

i=1 xi

N

and

population variance, σ2

=

PN

i=1 (xi − x̄)2

N

51

2.1 Sampling 2 STATISTICS

But how can we use the sample to estimate our pop-

ulation parameters?

First we define an unbiased estimator. An unbiased

estimator is when the expected value of the estimator is

exactly equal to the corresponding population parame-

ter, i.e.

if x̄ is the sample mean then the unbiased estimator is

E(x̄) = µ

where the sample mean is given by:

x̄ =

PN

i=1 xi

n

If S2

is the sample variance, then the unbiased esti-

mator is

E(S2

) = σ2

where the sample variance is given by:

S2

=

Pn

i=1 (xi − x̄)2

n − 1

2.1.1 Proof

From the CLT, we know:

E(X̄) = µ

and

V ar(X̄) =

σ2

n

Also

V ar(X̄) = E(X̄2

) − [E(X̄)]2

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-86-320.jpg)

![2.3 Regression and Correlation 2 STATISTICS

2.3 Regression and Correlation

2.3.1 Linear regression

We are often interested in looking at the relationship be-

tween two variables (bivariate data). If we can model

this relationship then we can use our model to make pre-

dictions.

A sensible first step would be to plot the data on a

scatter diagram, i.e. pairs of values (xi, yi)

Now we can try to fit a straight line through the data.

We would like to fit the straight line so as to minimise

the sum of the squared distances of the points from the

line. The different between the data value and the fitted

line is called the residual or error and the technique of

often referred to as the method of least squares.

59

2.3 Regression and Correlation 2 STATISTICS

If the equation of the line is given by

y = bx + a

then the error in y, i..e the residual of the ith

data point

(xi, yi) would be

ri = yi − y

= yi − (bxi + a)

We want to minimise

Pn=∞

n=1 r2

i , i.e.

S.R =

n=∞

X

n=1

r2

i =

n=∞

X

n=1

[yi − (bxi + a)]2

We want to find the b and a that minimise

Pn=∞

n=1 r2

i .

S.R =

X

y2

i − 2yi(bxi + a) + (bxi + a)2

=

X

y2

i − 2byixi − 2ayi + b2

x2

i + 2baxi + a2

or

= n ¯

y2 − 2bn ¯

xy − 2anȳ + b2

n ¯

x2 + 2banx̄ + na2

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-90-320.jpg)

![Mathematical Preliminaries

Introduction to Probability

Preliminaries

Randomness lies at the heart of …nance and whether terms uncertainty or risk are used, they refer to the

random nature of the …nancial markets. Probability theory provides the necessary structure to model the

uncertainty that is central to …nance. We begin by de…ning some basic mathematical tools.

The set of all possible outcomes of some given experiment is called the sample space. A particular

outcome ! 2 is called a sample point.

An event is a set of outcomes, i.e. .

To a set of basic outcomes !i we assign real numbers called probabilities, written P (!i) = pi: Then for

any event E;

P (E) =

X

!i2E

pi

Example 1

Experiment: A dice is rolled and the number appearing on top is observed. The sample space consists

of the 6 possible numbers:

= f1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6g

If the number 4 appears then ! = 4 is a sample point, clearly 4 2 .

Let 1, 2, 3 = events that an even, odd, prime number occurs respectively.

So

1 = f2; 4; 6g ; 2 = f1; 3; 5g ; 3 = f2; 3; 5g

1 [ 3 = f 2; 3; 4; 5; 6g event that an even or prime number occurs.

2 3 = f3; 5g event that odd and prime number occurs.

c

3 = f1; 4; 6g event that prime number does not occur (complement of event).

Example 2

Toss a coin twice and observe the sequence of heads (H) and tails (T) that appears. Sample space

= fHH, TT, HT, THg

Let 1 be event that at least one head appears, and 2 be event that both tosses are the same:

1 = fHH, HT, THg , 2 = fHH, TTg

1 2 = fHHg

Events are subsets of , but not all subsets of are events.

1

The basic properties of probabilities are

1. 0 pi 1

2. P ( ) =

X

i

pi = 1 (the sum of the probabilities is always 1).

Random Variables

Outcomes of experiments are not always numbers, e.g. 2 heads appearing; picking an ace from a deck

of cards. We need some way of assigning real numbers to each random event. Random variables assign

numbers to events.

Thus a random variable (RV) X is a function which maps from the sample space to the set of real

numbers

X : ! 2 ! R;

i.e. it associates a number X (!) with each outcome !:

Consider the example of tossing a coin and suppose we are paid £ 1 for each head and we lose £ 1 each time

a tail appears. We know that P (H) = P (T) =

1

2

: So now we can assign the following outcomes

P (1) =

1

2

P ( 1) =

1

2

Mathematically, if our random variable is X; then

X =

+1 if H

1 if T

or using the notation above X : ! 2 fH,Tg ! f 1; 1g :

The probability that the RV takes on each possible value is called the probability distribution.

If X is a RV then

P (X = a) = P (f! 2 : X (!) = ag)

is the probability that a occurs (or X maps onto a).

P (a X b) = probability that X lies in the interval [a; b] =

P (f! 2 : a X (!) bg)

X :

Domain

! R

Range (…nite)

X ( ) = fx1; ::::; xng = fxig1 i n

P [xi] = P [X = xi] = f (xi) 8 i:

So the earlier coin tossing example gives

P (X = 1) =

1

2

; P (X = 1) =

1

2

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-97-320.jpg)

![f (xi) is the probability distribution of X:

This is called a discrete probability distribution.

xi x1 x2 :::::::::::: xn

f (xi) f (x1) f (x2) :::::::::::: f (xn)

There are two properties of the distribution f (xi)

(i) f (xi) 0 8 i 2 [1; n]

(ii)

n

P

i=1

f (xi) = 1; i.e. sum of all probabilities is one.

Mean/Expectation

The mean measures the centre (average) of the distribution

= E [X] =

n

P

i=1

xi f (xi)

= x1f (x1) + x2f (x2) + ::::: + xnf (xn)

which is equal to the weighted average of all possible values of X together with associated probabilities.

This is also called the …rst moment.

Example:

xi 2 3 8

f (xi) 1

4

1

2

1

4

= E [X] =

3

P

i=1

xif (xi) = 2

1

4

+ 3

1

2

+ 8

1

4

= 4

Variance/Standard Deviation

This measures the spread (dispersion) of X about the mean.

Variance V [X] =

E (X )2

= E X2 2

=

n

P

i=1

x2

i f (xi) 2

= 2

E (X )2

is also called the second moment about the mean.

From the previous example we have = 4; therefore

V [X] = 22 1

4

+ 32 1

2

+ 82 1

4

16

= 5:5 = 2

! = 2:34

Rules for Manipulating Expectations

Suppose X; Y are random variables and ; ; 2 R are constant scalar quantities. Then

3

E [ X] = E [X]

E [X + Y ] = E [X] + E [Y ] ; (linearity)

V [ X + ] = 2

V [X]

E [XY ] = E [X] E [Y ] ;

V [X + Y ] = V [X] + V [Y ]

The last two are provided X; Y are independent.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-98-320.jpg)

![Continuous Random Variables

As the number of discrete events becomes very large, individual probabilities f (xi) ! 0: Now look at the

continuous case.

Instead of f (xi) we now have p (x) which is a continuous distribution called as probability density function,

PDF.

P (a X b) =

Z b

a

p (x) dx

The cumulative distribution function F (x) of a RV X is

F (x) = P (X x) =

Z x

1

p (x) dx

F (x) is related to the PDF by

p (x) =

dF

dx

(fundamental theorem of calculus) provided F (x) is di¤erentiable. However unlike F (x) ; p (x) may

have singularities (and may be unbounded).

Special Expectations:

Given any PDF p (x) of X:

Mean = E [X] =

Z

R

xp (x) dx:

Variance 2

= V [X] = E (X )2

=

Z

R

x2

p (x) dx 2

(2nd

moment about the mean).

The nth

moment about zero is de…ned as

n = E [Xn

]

=

Z

R

xn

p (x) dx:

In general, for any function h

E [h (X)] =

Z

R

h (x) p (x) dx:

where X is a RV following the distribution given by p (x) :

Moments about the mean are given by

E [(X )n

] ; n = 2; 3; :::

The special case n = 2 gives the variance 2

:

5

Skewness and Kurtosis

Having looked at the variance as being the second moment about the mean, we now discuss two further

moments centred about ; that provide further important information about the probability distribution.

Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of a distribution (i.e. lack of symmetry) about its mean. A

distribution that is identical to the left and right about a centre point is symmetric.

The third central moment, i.e. third moment about the mean scaled with 3

. This scaling allows us to

compare with other distributions.

E (X )3

3

is called the skew and is a measure of the skewness (a non-symmetric distribution is called skewed).

Any distribution which is symmetric about the mean has a skew of zero.

Negative values for the skewness indicate data that are skewed left and positive values for the skewness

indicate data that are skewed right.

By skewed left, we mean that the left tail is long relative to the right tail. Similarly, skewed right means

that the right tail is long relative to the left tail.

The fourth centred moment scaled by the square of the variance, called the kurtosis is de…ned

E (X )4

4

:

This is a measure of how much of the distribution is out in the tails at large negative and positive values

of X:

The 4th

central moment is called Kurtosis and is de…ned as

Kurtosis =

E (X )4

4

normal random variable has Kurtosis of 3 irrespective of its mean and standard deviation. Often when

comparing a distribution to the normal distribution, the measure of excess Kurtosis is used, i.e. Kurtosis

of distribution 3.

If a random variable has Kurtosis greater than 3 is called Leptokurtic, if is has Kurtosis less than 3 it

is called platykurtic Leptokurtic is associated with PDF’

s that are simultaneously peaked and have fat tails.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-99-320.jpg)

![Normal Distribution

The normal (or Gaussian) distribution N ( ; 2

) with mean and standard deviation and 2

in turn

is de…ned in terms of its density function

p (x) =

1

p

2

exp

(x )2

2 2

!

:

For the special case = 0 and = 1 it is called the standard normal distribution N (0; 1) :

This is also veri…ed by making the substitution

=

x

in p (x) which gives

( ) =

1

p

2

exp

1

2

2

and clearly has zero mean and unit variance:

E

X

=

1

E [X ] = 0;

V

X

= V

X

Now V [ X + ] = 2

V [X] (standard result), hence

1

2

V [X] =

1

2

: 2

= 1

Its cumulative distribution function is

F (x) =

1

p

2

Z x

1

e

1

2

2

d = P ( 1 X x) :

The skewness of N (0; 1) is zero and its kurtosis is 3:

7

Correlation

The covariance is useful in studying the statistical dependence between two random variables. If X; Y are

RV’

s, then their covariance is de…ned as:

Cov (X; Y ) = E

2

6

4

0

@X E (X)

| {z }

= x

1

A

0

B

@Y E (Y )

| {z }

= y

1

C

A

3

7

5

= E [XY ] x y

which we denote as XY : Note:

Cov (X; X) = E (X x)2

= 2

:

X; Y are correlated if

E (X x) Y y 6= 0:

We can then de…ne an important dimensionless quantity (used in …nance) called the correlation coe¢ cient

and denoted as XY (X; Y ) where

XY =

Cov (X; Y )

x y

:

The correlation can be thought of as a normalised covariance, as j XY j 1; for which the following

conditions are properties:

i. (X; Y ) = (Y; X)

ii. (X; X) = 1

iii. 1 1

XY = 1 ) perfect negative correlation

XY = 1 )perfect correlation

XY = 0 ) X; Y uncorrelated

Why is the correlation coe¢ cient bounded by 1? Justi…cation of this requires a result called the Cauchy-

Schwartz inequality. This is a theorem which most students encounter for the …rst time in linear algebra

(although we have not discussed this). Let’

s start o¤ with the version for random variables (RVs) X and

Y , then the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality is

[E [XY ]]2

E X2

E Y 2

:

We know that the covariance of X; Y is

XY = E [(X X) (Y Y )]

If we put

V [X] = 2

X = E (X X)2

V [Y ] = 2

Y = E (Y Y )2

:

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-100-320.jpg)

![From Cauchy-Schwartz we have

(E [(X X) (Y Y )])2

E (X X)2

E (Y Y )2

or we can write

2

XY

2

X

2

Y

Divide through by 2

X

2

Y

2

XY

2

X

2

Y

1

and we know that the left hand side above is 2

XY , hence

2

XY =

2

XY

2

X

2

Y

1

and since XY is a real number, this implies j XY j 1 which is the same as

1 XY +1:

Central Limit Theorem

This concept is fundamental to the whole subject of …nance.

Let Xi be any independent identically distributed (i.i.d) random variable with mean and variance 2

;

i.e. X D ( ; 2

) ; where D is some distribution: If we put

Sn =

n

P

i=1

Xi

Then

(Sn n )

p

n

has a distribution that approaches the standard normal distribution as n ! 1:

The distribution of the sum of a large number of independent identically distributed variables will be

approximately normal, regardless of the underlying distribution. That is the beauty of this result.

Conditions:

The Normal distribution is the limiting behaviour if you add many random numbers from any basic-building

block distribution provided the following is satis…ed:

1. Mean of distribution must be …nite and constant

2. Standard deviation of distribution must be …nite and constant

This is a measure of how much of the distribution is out in the tails at large negative and positive values

of X:

9

Moment Generating Function

The moment generating function of X; denoted MX ( ) is given by

MX ( ) = E e X

=

Z

R

e x

p (x) dx

provided the expectation exists. We can expand as a power series to obtain

MX ( ) =

1

X

n=0

n

E (Xn

)

n!

so the nth

moment is the coe¢ cient of n

=n!; or the nth

derivative evaluated at zero.

How do we arrive at this result?

We use the Taylor series expansion for the exponential function:

Z

R

e x

p (x) dx =

Z

R

1 + x +

( x)2

2!

+

( x)3

3!

+ ::::::

!

p (x) dx

=

Z

R

p (x) dx

| {z }

1

+

Z

R

xp (x) dx

| {z }

E(X)

+

2

2!

Z

R

x2

p (x) dx

| {z }

E(X2)

+

3

3!

Z

R

x3

p (x) dx

| {z }

E(X3)

+ ::::

= 1 + E (X) +

2

2!

E X2

+

3

3!

E X3

+ ::::

=

1

X

n=0

n

E (Xn

)

n!

:

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-101-320.jpg)

![Calculating Moments

The kth

moment mk of the random variable X can now be obtained by di¤erentiating, i.e.

mk = M

(k)

X ( ) ; k = 0; 1; 2; :::

M

(k)

X ( ) =

dk

d k

MX ( )

=0

So what is this result saying? Consider MX ( ) =

1

X

n=0

n

E(Xn)

n!

MX ( ) = 1 + E [X] +

2

2!

E X2

+

3

3!

E X3

+ :::: +

n

n!

E [Xn

]

As an example suppose we wish to obtain the second moment; di¤erentiate twice with respect to

d

d

MX ( ) = E [X] + E X2

+

2

2

E X3

+ :::: +

n 1

(n 1)!

E [Xn

]

and for the second time

d2

d 2 MX ( ) = E X2

+ E X3

+ :::: +

n 2

(n 2)!

E [Xn

] :

Setting = 0; gives

d2

d 2 MX (0) = E X2

which captures the second moment E [X2

]. Remember we will already have an expression for MX ( ) :

A useful result in …nance is the MGF for the normal distribution. If X N ( ; 2

), then we can construct

a standard normal N (0; 1) by setting =

X

=) X = + :

The MGF is

MX ( ) = E e x

= E e ( + )

= e E e

So the MGF of X is therefore equal to the MGF of but with replaced by :This is much nicer than

trying to calculate the MGF of X N ( ; 2

) :

E e =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e x

e x2=2

dx =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e x x2=2

dx

=

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2 (x2 2 x+ 2 2

)dx =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

(x )2

+ 1

2

2

dx

= e

1

2

2 1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

(x )2

dx

Now do a change of variable - put u = x

E e = e

1

2

2 1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

u2

du

= e

1

2

2

11

Thus

MX ( ) = e E e

= e + 1

2

2 2

To get the simpler formula for a standard normal distribution put = 0; = 1 to get MX ( ) = e

1

2

2

:

We can now obtain the …rst four moments for a standard normal

m1 =

d

d

e

1

2

2

=0

= e

1

2

2

=0

= 0

m2 =

d2

d 2 e

1

2

2

=0

= 2

+ 1 e

1

2

2

=0

= 1

m3 =

d3

d 3 e

1

2

2

=0

= 3

+ 3 e

1

2

2

=0

= 0

m4 =

d4

d 4 e

1

2

2

=0

= 4

+ 6 2

+ 3 e

1

2

2

=0

= 3

The latter two are particularly useful in calculating the skew and kurtosis.

If X and Y are independent random variables then

MX+Y ( ) = E e (x+y)

= E e x

e y

= E e x

E e y

= MX ( ) MY ( ) :

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-102-320.jpg)

![Review of Di¤erential Equations

Cauchy Euler Equation

An equation of the form

Ly = ax2 d2

y

dx2

+ x

dy

dx

+ cy = g (x)

is called a Cauchy-Euler equation.

To solve the homogeneous part, we look for a solution of the form

y = x

So y0

= x 1

! y00

= ( 1) x 2

, which upon substitution yields the quadratic, A.E.

a 2

+ b + c = 0;

where b = ( a) which can be solved in the usual way - there are 3 cases to consider, depending upon

the nature of b2

4ac.

Case 1: b2

4ac 0 ! 1, 2 2 R - 2 real distinct roots

GS y = Ax 1

+ Bx 2

Case 2: b2

4ac = 0 ! = 1 = 2 2 R - 1 real (double fold) root

GS y = x (A + B ln x)

Case 3: b2

4ac 0 ! = i 2 C - pair of complex conjugate roots

GS y = x (A cos ( ln x) + B sin ( ln x))

Example

Consider the following Euler type problem

1

2

2

S2 d2

V

dS2

+ rS

dV

dS

rV = 0;

V (0) = 0; V (S ) = S E

where the constants E; S ; ; r 0. We are given that the roots of A.E m are real with m 0 m+:

Look for a solution of the form General Solution is

V (S) = ASm+

+ BSm

:

V (0) = 0 =) B = 0 else we have division by zero

V (S) = ASm+

15

To …nd A use the second condition V (S ) = S E

V (S ) = A (S )m+

= S E ! A =

S E

(S )m+

hence

V (S) =

S E

(S )m+

(S)m+

= (S E)

S

S

m+

:

Similarity Methods

f (x; y) is homogeneous of degree t 0 if f ( x; y) = t

f (x; y) :

1. f (x; y) =

p

(x2 + y2)

f ( x; y) =

q

( x)2

+ ( y)2

=

p

[(x2 + y2)] = f (x; y)

g (x; y) = x+y

x y

then

g ( x; y) = x+ y

x y

= 0 x+y

x y

= 0

g (x; y)

2. h (x; y) = x2

+ y3

h ( x; y) = ( x)2

+ ( y)3

= 2

x2

+ 3

y3

6= t

x2

+ y3

for any t. So h is not homogeneous.

Consider the function

F (x; y) = x2

x2+y2

If for any 0 we write

x0

= x; y0

= y

then

dy0

dx0

=

dy

dx

; x2

x2+y2 = x02

x02

+y02 :

We see that the equation is invariant under the change of variables. It also makes sense to look for a

solution which is also invariant under the transformation. One choice is to write

v =

y

x

=

y0

x0

so write

y = vx:

De…nition The di¤erential equation

dy

dx

= f (x; y) is said to be homogeneous when f (x; y) is homogeneous

of degree t for some t:

Method of Solution

Put y = vx where v is some (as yet) unknown function. Hence we have

dy

dx

=

d

dx

(vx) = x

dv

dx

+ v

dx

dx

= v0

x + v

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-104-320.jpg)

![Using a Binomial random walk

The earlier results can also be obtained using a symmetric random walk. Consider the following (two step)

binomial random walk. So the random variable can either rise or fall with equal probability.

y is the random variable and t is a time step. y is the size of the move in y:

P [ y] = P [ y] = 1=2:

Suppose we are at (y0

; t0

) ; how did we get there? At the previous step time step we must have been at one

of (y0

+ y; t0

t) or (y0

y; t0

t) :

So

p (y0

; t0

) = 1

2

p (y0

+ y; t0

t) + 1

2

p (y0

y; t0

t)

Taylor series expansion gives

p (y0

+ y; t0

t) = p (y0

; t0

)

@p

@t0

t +

@p

@y0

y + 1

2

@2

p

@y02 y2

+ :::

p (y0

y; t0

t) = p (y0

; t0

)

@p

@t0

t

@p

@y0

y + 1

2

@2

p

@y02 y2

+ :::

Substituting into the above

p (y0

; t0

) = 1

2

p (y0

; t0

)

@p

@t0

t +

@p

@y0

y + 1

2

@2

p

@y02 y2

+1

2

p (y0

; t0

)

@p

@t0

t

@p

@y0

y + 1

2

@2

p

@y02 y2

33

0 =

@p

@t0

t + 1

2

@2

p

@y02 y2

@p

@t0

= 1

2

y2

t

@2

p

@y02

Now take limits. This only makes sense if y2

t

is O (1) ; i.e. y2

O ( t) and letting y; t ! 0 gives the

equation

@p

@t0

= 1

2

@2

p

@y02

This is called the forward Kolmogorov equation. Also called Fokker Planck equation.

It shows how the probability density of future states evolves, starting from (y; t) :

A particular solution of this is

p (y; t; y0

; t0

) =

1

p

2 (t0 t)

exp

(y0

y)2

2 (t0 t)

!

At t0

= t this is equal to (y0

y). The particle is known to start from (y; t) and its density is normal

with mean y and variance t0

t:

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-113-320.jpg)

![Mathematical Preliminaries

Introduction to Probability - Moment Generating Function

The moment generating function of X; denoted MX ( ) is given by

MX ( ) = E e x

=

Z

R

e x

p (x) dx

provided the expectation exists. We can expand as a power series to obtain

MX ( ) =

1

X

n=0

n

E (Xn

)

n!

so the nth

moment is the coe¢ cient of n

=n!; or the nth

derivative evaluated at zero.

How do we arrive at this result?

We use the Taylor series expansion for the exponential function:

Z

R

e x

p (x) dx =

Z

R

1 + x +

( x)2

2!

+

( x)3

3!

+ ::::::

!

p (x) dx

=

Z

R

p (x) dx

| {z }

1

+

Z

R

xp (x) dx

| {z }

E(X)

+

2

2!

Z

R

x2

p (x) dx

| {z }

E(X2)

+

3

3!

Z

R

x3

p (x) dx

| {z }

E(X3)

+ ::::

= 1 + E (X) +

2

2!

E X2

+

3

3!

E X3

+ ::::

=

1

X

n=0

n

E (Xn

)

n!

:

1

Calculating Moments

The kth

moment mk of the random variable X can now be obtained by di¤erentiating, i.e.

mk = M

(k)

X ( ) ; k = 0; 1; 2; :::

M

(k)

X ( ) =

dk

d k

MX ( )

=0

So what is this result saying? Consider MX ( ) =

1

X

n=0

n

E(Xn)

n!

MX ( ) = 1 + E [X] +

2

2!

E X2

+

3

3!

E X3

+ :::: +

n

n!

E [Xn

]

As an example suppose we wish to obtain the second moment; di¤erentiate twice with respect to

d

d

MX ( ) = E [X] + E X2

+

2

2

E X3

+ :::: +

n 1

(n 1)!

E [Xn

]

and for the second time

d2

d 2 MX ( ) = E X2

+ E X3

+ :::: +

n 2

(n 2)!

E [Xn

] :

Setting = 0; gives

d2

d 2 MX (0) = E X2

which captures the second moment E [X2

]. Remember we will already have an expression for MX ( ) :

A useful result in …nance is the MGF for the normal distribution. If X N ( ; 2

), then we can construct

a standard normal N (0; 1) by setting =

X

=) X = + :

The MGF is

MX ( ) = E e x

= E e ( + )

= e E e

So the MGF of X is therefore equal to the MGF of but with replaced by :This is much nicer than

trying to calculate the MGF of X N ( ; 2

) :

E e =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e x

e x2=2

dx =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e x x2=2

dx

=

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2 (x2 2 x+ 2 2

)dx =

1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

(x )2

+ 1

2

2

dx

= e

1

2

2 1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

(x )2

dx

Now do a change of variable - put u = x

E e = e

1

2

2 1

p

2

Z 1

1

e

1

2

u2

du

= e

1

2

2

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-116-320.jpg)

![Di¤usion Process

G is called a di¤usion process if

dG (t) = A (G; t) dt + B (G; t) dW (t) (1)

This is also an example of a Stochastic Di¤erential Equation (SDE) for the process G and consists of two

components:

1. A (G;t) dt is deterministic –coe¢ cient of dt is known as the drift of the process.

2. B (G; t) dW is random – coe¢ cient of dW is known as the di¤usion or volatility of the process.

We say G evolves according to (or follows) this process.

For example

dG (t) = (G (t) + G (t 1)) dt + dW (t)

is not a di¤usion (although it is a SDE)

A 0 and B 1 reverts the process back to Brownian motion

Called time-homogeneous if A and B are not dependent on t:

dG 2

= B2

dt:

We say (1) is a SDE for the process G or a Random Walk for dG:

The di¤usion (1) can be written in integral form as

G (t) = G (0) +

Z t

0

A (G; ) d +

Z t

0

B (G; ) dW ( )

Remark: A di¤usion G is a Markov process if - once the present state G (t) = g is given, the past

fG ( ) ; tg is irrelevant to the future dynamics.

We have seen that Brownian motion can take on negative values so its direct use for modelling stock prices

is unsuitable. Instead a non-negative variation of Brownian motion called geometric Brownian motion

(GBM) is used

If for example we have a di¤usion G (t)

dG = Gdt + GdW (2)

then the drift is A (G; t) = G and di¤usion is B (G; t) = G:

The process (2) is also called Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM).

Brownian motion W (t) is used as a basis for a wide variety of models. Consider a pricing process

fS (t) : t 2 R+g: we can model its instantaneous change dS by a SDE

dS = a (S; t) dt + b (S; t) dW (3)

By choosing di¤erent coe¢ cients a and b we can have various properties for the di¤usion process.

A very popular …nance model for generating asset prices is the GBM model given by (2). The instantaneous

return on a stock S (t) is a constant coe¢ cient SDE

dS

S

= dt + dW (4)

where and are the return’

s drift and volatility, respectively.

5

An Extension of Itô’

s Lemma (2D)

Now suppose we have a function V = V (S; t) where S is a process which evolves according to (4) : If

S ! S + dS; t ! t + dt then a natural question to ask is what is the jump in V ? To answer this we

return to Taylor, which gives

V (S + dS; t + dt)

= V (S; t) +

@V

@t

dt +

@V

@S

dS +

1

2

@2

V

@S2

dS2

+ O dS3

; dt2

So S follows

dS = Sdt + SdW

Remember that

E (dW) = 0; dW2

= dt

we only work to O (dt) - anything smaller we ignore and we also know that

dS2

= 2

S2

dt

So the change dV when V (S; t) ! V (S + dS; t + dt) is given by

dV =

@V

@t

dt +

@V

@S

[S dt + S dW] +

1

2

2

S2 @2

V

@S2

dt

Re-arranging to have the standard form of a SDE dG = a (G; t) dt + b (G; t) dW gives

dV =

@V

@t

+ S

@V

@S

+

1

2

2

S2 @2

V

@S2

dt + S

@V

@S

dW. (5)

This is Itô’

s Formula in two dimensions.

Naturally if V = V (S) then (5) simpli…es to the shorter version

dV = S

dV

dS

+

1

2

2

S2 d2

V

dS2

dt + S

dV

dS

dW. (6)

Examples: In the following cases S evolves according to GBM.

Given V = t2

S3

obtain the SDE for V; i.e. dV: So we calculate the following terms

@V

@t

= 2tS3

;

@V

@S

= 3t2

S2

!

@2

V

@S2

= 6t2

S:

We now substitute these into (5) to obtain

dV = 2tS3

+ 3 t2

S3

+ 3 2

S3

t2

dt + 3 t2

S3

dW.

Now consider the example V = exp (tS)

Again, function of 2 variables. So

@V

@t

= S exp (tS) = SV

@V

@S

= t exp (tS) = tV

@2

V

@S2

= t2

V

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-118-320.jpg)

![Substitute into (5) to get

dV = V S + tS +

1

2

2

S2

t2

dt + ( StV ) dW:

Not usually possible to write the SDE in terms of V but if you can do so - do not struggle to …nd a

relation if it does not exist. Always works for exponentials.

One more example: That is S (t) evolves according to GBM and V = V (S) = Sn

: So use

dV = S

dV

dS

+

1

2

2

S2 d2

V

dS2

dt + S

dV

dS

dW.

V 0

(S) = nSn 1

! V 00

(S) = n (n 1) Sn 2

Therefore Itô gives us dV =

SnSn 1

+

1

2

2

S2

n (n 1) Sn 2

dt + SnSn 1

dW

dV = nSn

+

1

2

2

n (n 1) Sn

dt + [ nSn

] dW

Now we know V (S) = Sn

; which allows us to write

dV = V n +

1

2

2

n (n 1) dt + [ n] V dW

with drift = V n + 1

2

2

n (n 1) and di¤usion = nV:

7

Important Cases - Equities and Interest Rates

If we now consider S which follows a lognormal random walk, i.e. V = log(S) then substituting into (6)

gives

d ((log S)) =

1

2

2

dt + dW

Integrating both sides over a given time horizon ( between t0 and T )

Z T

t0

d ((log S)) =

Z T

t0

1

2

2

dt +

Z T

t0

dW (T t0)

we obtain

log

S (T)

S (t0)

=

1

2

2

(T t0) + (W (T) W (t0))

Assuming at t0 = 0, W (0) = 0 and S (0) = S0 the exact solution becomes

ST = S0 exp

1

2

2

T +

p

T . (7)

(7) is of particular interest when considering the pricing of a simple European option due to its non path

dependence. Stock prices cannot become negative, so we allow S, a non-dividend paying stock to evolve

according to the lognormal process given above - and acts as the starting point for the Black-Scholes

framework.

However is replaced by the risk-free interest rate r in (7) and the introduction of the risk-neutral measure

- in particular the Monte Carlo method for option pricing.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-119-320.jpg)

![Interest rates exhibit a variety of dynamics that are distinct from stock prices, requiring the development

of speci…c models to include behaviour such as return to equilibrium, boundedness and positivity. Here we

consider another important example of a SDE, put forward by Vasicek in 1977. This model has a mean

reverting Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process for the short rate and is used for generating interest rates, given by

drt = ( rt) dt + dWt. (8)

So drift = ( rt) and volatility = .

refers to the reversion rate and (= r) denotes the mean rate, and we can rewrite this random walk (7)

for dr as

drt = (rt r) dt + dWt.

By setting t = rt r, t is a solution of

d t = tdt + dWt; 0 = ; (9)

hence it follows that t is an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process and an analytic solution for this equation exists.

(9) can be written as d t + tdt = dWt:

Multiply both sides by an integrating factor e t

e t

(d t + t) dt = e t

dWt

d e t

t = e t

dWt

Integrating over [0; t] gives

Z t

0

d (e s

s) =

Z t

0

e s

dWs

e s

sjt

0 =

Z t

0

e s

dWs ! e t

t 0 =

Z t

0

e s

dWs

t = e t

+

Z t

0

e (s t)

dWs: (10)

By using integration by parts, i.e.

Z

v du = uv

Z

u dv we can simplify (10).

u = Ws

v = e (s t)

! dv = e (s t)

ds

Therefore Z t

0

e (s t)

dWs = Wt

Z t

0

e (s t)

Ws ds

and we can write (10) as

t = e t

+ Wt

Z t

0

e (s t)

Ws ds

allowing numerical treatment for the integral term.

9

Higher Dimensional Itô

Consider the case where N shares follow the usual Geometric Brownian Motions, i.e.

dSi = iSidt + iSidWi;

for 1 i N: The share price changes are correlated with correlation coe¢ cient ij: By starting with a

Taylor series expansion

V (t + t; S1 + S1; S2 + S2; :::::; SN + SN ) =

V (t; S1; S2; :::::; SN ) + @V

@t

+

N

P

i=1

@V

@Si

dSi +

1

2

N

P

i=1

N

P

j=i

@2V

@Si@Sj

+ ::::

which becomes, using dWidWj = ijdt

dV =

@V

@t

+

N

P

i=1

iSi

@V

@Si

+

1

2

N

P

i=1

N

P

j=i

i j ijSiSj

@2

V

@Si@Sj

!

dt +

N

P

i=1

iSi

@V

@Si

dWi:

We can integrate both sides over 0 and t to give

V (t; S1; S2; :::::; SN ) = V (0; S1; S2; :::::; SN ) +

Z t

0

@V

@

+

N

P

i=1

iSi

@V

@Si

+ 1

2

N

P

i=1

N

P

j=i

i j ijSiSj

@2V

@Si@Sj

!

d

+

Z t

0

N

P

i=1

iSi

@V

@Si

dWi:

Discrete Time Random Walks

When simulating a random walk we write the SDE given by (6) in discrete form

S = Si+1 Si = rSi t + Si

p

t

which becomes

Si+1 = Si 1 + r t +

p

t : (11)

This gives us a time-stepping scheme for generating an asset price realization if we know S0, i.e. S (t) at

t = 0: N (0; 1) is a random variable with a standard Normal distribution.

Alternatively we can use discrete form of the analytical expression (7)

Si+1 = Si exp r

1

2

2

t +

p

t :

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-120-320.jpg)

![So we now start generating random numbers. In C++ we produce uniformly distributed random variables

and then use the Box Muller transformation (Polar Marsaglia method) to convert them to Gaussians.

This can also be generated on an Excel spreadsheet using the in-built random generator function RAND().

A crude (but useful) approximation for can be obtained from

12

X

i=1

RAND () 6

where RAND() U [0; 1] :

A more accurate (but slower) can be computed using NORMSINV(RAND ()) :

11

Dynamics of Vasicek Model

The Vasicek model

drt = (r rt) dt + dWt

is an example of a Mean Reverting Process - an important property of interest rates. refers to the

reversion rate (also called the speed of reversion) and r denotes the mean rate.

acts like a spring. Mean reversion means that a process which increases has a negative trend ( pulls

it down to a mean level r), and when rt decreases on average pulls it back up to r:

In discrete time we can approximate this by writing (as earlier)

ri+1 = ri + (r ri) t +

p

t

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5

To gain an understanding of the properties of this model, look at dr in the absence of randomness

dr = (r r) dt

Z

dr

(r r)

=

Z

dt

r (t) = r + k exp ( kt)

So controls the rate of exponential decay.

One of the disadvantages of the Vasicek model is that interest rates can become negative. The Cox Ingersoll

Ross (CIR) model is similar to the above SDE but is scaled with the interest rate:

drt = (r rt) dt +

p

rtdWt:

If rt ever gets close to zero, the amount of randomness decreases, i.e. di¤usion ! 0; therefore the drift

dominates, in particular the mean rate.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-121-320.jpg)

![Producing Standardized Normal Random Variables

Consider the RAND() function in Excel that produces a uniformly distributed random number over 0 and

1; written Unif[0;1]: We can show that for a large number N,

lim

N!1

r

12

N

N

P

1

Unif[0;1]

N

2

N (0; 1) :

Introduce Ui to denote a uniformly distributed random variable over [0; 1] and sum up. Recall that

E [Ui] = 1

2

V [Ui] = 1

12

The mean is then

E

N

P

i=1

Ui = N=2

so subtract o¤ N=2; so we examine the variance of

N

P

1

Ui

N

2

V

N

P

1

Ui

N

2

=

N

P

1

V [Ui]

= N=12

As the variance is not 1, write

V

N

P

1

Ui

N

2

for some 2 R: Hence 2 N

12

= 1 which gives =

p

12=N which normalises the variance. Then we achieve

the result r

12

N

N

P

1

Ui

N

2

:

Rewrite as

N

P

1

Ui N 1

2

q

1

12

p

N

:

and for N ! 1 by the Central Limit Theorem we get N (0; 1)

13

Generating Correlated Normal Variables

Consider two uncorrelated standard Normal variables 1 and 2 from which we wish to form a correlated

pair 1; 2 ( N (0; 1)), such that E [ 1 2] = : The following scheme can be used

1. E [1] = E [2] = 0 ; E [2

1] = E [2

2] = 1 and E [12] = 0 (* 1; 2 are uncorrelated) :

2. Set 1 = 1 and 2 = 1 + 2 (i.e. a linear combination).

3. Now

E [ 1 2] = = E [1 ( 1 + 2)]

E [1 ( 1 + 2)] =

E 2

1 + E [12] = ! =

E 2

2 = 1 = E ( 1 + 2)2

= E 2

2

1 + 2

2

2 + 2 12

= 2

E 2

1 + 2

E 2

2 + 2 E [12] = 1

2

+ 2

= 1 ! =

p

1 2

4. This gives 1 = 1 and 2 = 1+

p

1 2 2 which are correlated standardized Normal variables.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-122-320.jpg)

![Transition Probability Density Functions for Stochastic Di¤erential Equa-

tions

To match the mean and standard deviation of the trinomial model with the continuous-time random walk

we choose the following de…nitions for the probabilities

+

(y; t) =

1

2

t

y2

B2

(y; t) + A (y; t) y ;

(y; t) =

1

2

t

y2

B2

(y; t) A (y; t) y

We …rst note that the expected value is

+

( y) + ( y) + 1 +

(0)

= +

y

We already know that the mean and variance of the continuous time random walk given by

dy = A (y; t) dt + b (y; t) dW

is, in turn,

E [dy] = Adt

V [dy] = B2

dt:

So to match the mean requires

+

y = A t

The variance of the trinomial model is E [u2

] E2

[u] and hence becomes

( y)2 +

+ + 2

( y)2

= ( y)2 +

+ + 2

:

We now match the variances to get

( y)2 +

+ + 2

= B2

t

First equation gives

+

= + A t

y

which upon substituting into the second equation gives

( y)2

+ + +

2

= B2

t

where = A t

y

: This simpli…es to

2 + 2

= B2 t

( y)2

which rearranges to give

=

1

2

B2 t

( y)2 + 2

=

1

2

B2 t

( y)2 + A t

y

2

A t

y

=

1

2

t

( y)2 B2

+ A2

t A y

15

t is small compared with y and so

=

1

2

t

( y)2 B2

A y :

Then

+

= + A t

y

=

1

2

t

( y)2 B2

+ A y :

Note

+

+ ( y)2

= B2

t

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-123-320.jpg)

![about the eventual outcome ! of the three coin tosses. All one can say is that ! =

2 ; and ! 2 and so

F0 = f ; ;g.

Now de…ne the following two subsets of :

AU = fUUU; UUD; UDU; UDDg ; AD = fDUU; DUD; DDU; DDDg :

We see AU is the subset of outcomes where a Head appears on the …rst throw, AD is the subset of outcomes

where a Tail lands on the …rst throw. After the …rst trading period t = 1,(11am) we know whether the

initial move was an up move or down move. Hence

F1 = f ; ;; AU ; ADg

De…ne also

AUU = fUUU; UUDg ; AUD = fUDU; UDDg ;

ADU = fDUU; DUDg ; ADD = fDDU; DDDg

corresponding to the events that the …rst two coin tosses result in HH; HT; TH; TT respectively. This

is the information we have at the end of the 2nd trading period t = 2,(1 pm). This means at the end of

the second trading period we have accumulated increasing information. Hence

F2 = f ; ;; AU ; AD; AUU ; AUD; ADU ; ADD + all unions of theseg ;

which can be written as follows

F2 = f ; ;; AU ; AD; AUU ; AUD; ADU ; ADD

AUU [ ADU ; AUU [ ADD; AUD [ ADU ; AUD [ ADD

Ac

UU ; Ac

UD; Ac

DU ; Ac

DDg

We see

F0 F1 F2

Then F2 is a algebra which contains the information of the …rst two tosses of the information up to

time 2. This is because, if you know the outcome of the …rst two tosses, you can say whether the outcome

! 2 of all three tosses satis…es ! 2 A or ! =

2 A for each A 2 F2:

Similarly, F3 F; the set of all subsets of ; contains full information about the outcome of all three

tosses. The sequence of increasing algebras F = fF0; F1; F2; F3g is a …ltration.

Adapted Process A stochastic process St is said to be adapted to the …ltration Ft (or Ft measurable or

Ft adapted) if the value of S at time t is known given the information set Ft:

We place a probability measure P on f ; Fg : P is a special type of function, called a measure which

assigns probabilities to subsets (i.e. the outcomes); the theory also comes from Measure Theory. Whereas

cumulative density functions (CDF) are de…ned on intervals such as R; probability measures are de…ned

on general sets, giving greater power, generalisation and ‡

exibility. A probability measure P is a function

mapping P : F ! [0; 1] with the properties

(i) P ( ) = 1;

(ii) if A1; A2; :::: is a sequence of disjoint sets in F; then P (

S1

k=1 Ak) =

1

X

k=1

P (Ak) :

11

Example Recall the usual coin toss game with the earlier de…ned results. As the outcomes are equiprobable

the probability measure de…ned as P (!1) = 1

2

= P (!2) :

The interpretation is that for a set A 2F there is a probability in [0; 1] that the outcome of a random

experiment will lie in the set A: We think of P (A) as this probability. The A 2F is called an event. For

A 2F we can de…ne

P (A) :=

X

!2A

P (!) ; (*)

as A has …nitely many elements. Letting the probability of H on each coin toss be p 2 (0; 1) ; so that the

probability of T is q = 1 p. For each ! = (!1; !2; : : : !n) 2 we de…ne

P (!) := pNumber of H in !

qNumber of T in !

:

Then for each A 2F we de…ne P (A) according to ( ) :

In the …nite coin toss space, for each t 2 T let Ft be the algebra generated by the …rst t coin tosses.

This is a algebra which encapsulates the information one has if one observes the outcome of the …rst

t coin tosses (but not the full outcome ! of all n coin tosses). Then Ft is composed of all the sets A such

that Ft is indeed a algebra, and such that if the outcome of the …rst t coin tosses is known, then we

can say whether ! 2 A or ! =

2 A; for each A 2 Ft: The increasing sequence of algebras (Ft)t2T is an

example of a …ltration. We use this notation when working in continuous time.

When moving to continuous time we will write (Ft)t2[0;T] :

If we are concerned with developing a more measure theory based rigorous approach then working structures

such as algebras becomes more important - so we do not need to worry too much about this in our

…nancial mathematics setting.

We can compute the probability of any event. For instance,

P (AU ) = P (H on …rst toss) = P fUUU; UUD; UDU; UDDg

= p3

+ 2p2

q + pq2

= p;

and similarly P (AT ) = q: This agrees with the mathematics and our intuition.

Explanation of probability measure: If the number of basic events is very large we may prefer to

think of a continuous probability distribution. As the number of discrete events tends to in…nity, the

probability of any individual event usually tends to zero. In terms of random variables, the probability

that the random variable X takes a given value tends to zero.

So, the individual probabilities pi are no longer useful. Instead we have a probability density function p (x)

with the property that

Pr (x X x + dx) = p (x) dx

for any in…nitesimal interval of length dx (think of this as a limiting process starting with a small interval whos

It is also called a density because it is the probability of …nding X on an interval of length dx divided by

the length of the interval. Recall that the following are analogous

Z 1

1

p (x) dx = 1

X

i

pi = 1:

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matematicasciffdob-240629235208-7f2b1627/85/Matematicas-FINANCIERAS-CIFF-dob-pdf-131-320.jpg)

![The (cumulative) distribution function of a random variable is de…ned by

P (x) = Pr (X x) :