1) Imaging plays a fundamental role in diagnosing and monitoring Marfan syndrome by evaluating features in the cardiovascular, skeletal, and other organ systems.

2) Echocardiography, CT, and MRI are used to monitor dilation of the aorta and risk of dissection, with surgery recommended when the ascending aorta reaches 5 cm.

3) Post-operative imaging with CT or MRI is used to define graft anatomy and identify complications after aortic root replacement surgery for Marfan syndrome.

![Page 2 of 44

Learning objectives

The purpose of our educational exhibit is to:

1)be familiar with the clinical presentation and radiological manifestations of Marfan

syndrome;

2)understand the role of echocardiography, ECG-gated multidector computed

tomography and MRI imaging for the evaluation of aortic involvement;

3)illustrate the different radiological findings for the different organs affected by Marfan

syndrome including cardiovascular system, chest and spine;

4)describe the normal and pathological findings in patients with chronic aortic dissection

or after surgery.

Background

Marfan's syndrome is a multisystemic connective tissue disorder of autosomal dominant

heritance. Fig. 1 on page 3

It exhibits complete penetrance and variable expression. The birth incidence is around 1

in 9800. About 25% of cases represent sporadic mutations [1].

In 1991, fibrillin-1 gene mutation on chromosome 15q21 was identified as a cause

of Marfan syndrome. FBN1 gene encodes the microfibrillar protein fibrillin 1. Many

mutations of FBN1 gene can lead to defects in the synthesis of protein fibrillin [2]. These

defects induce dysfunction of microfibrills and impairment of elastic tissue homeostasis.

It produces structural disintegration of vascular connective tissue, which results in

aneurysm formation and dissection[3].

Recently, mutations in the transforming growth factor #-receptor 2 gene (TGFBR2) on

chromosome 3p24 and in the TGFBR1 on chromosome 9 were also found in patients

with apparent Marfan syndrome .

Despite the progress made in the molecular basis, the diagnosis continues to depend

on clinical features. It is based on the Berlin classification of 1988 , which was revised](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-2-320.jpg)

![Page 3 of 44

to create the Ghent nosology in 1996. A diagnosis of marfan syndrome requires 2 major

features in two different systems and one minor feature of a third system, or one major

and four minor features[4]. Fig. 2 on page 4

A further revision of the Ghent nosology was proposed in 2010. More weight was given

to aortic root aneurysm or dissection, ectopia lentis, and molecular genetic screening

for FBN1 and TGFBR1 or 2;and a concept that additional diagnostic considerations are

required was introduced if a patient shows unusual findings[5]. This new nosology seems

to led to different diagnosis in 15% to 30% of cases[5, 6]. Fig. 3 on page 5

Cardiovascular manifestations include annuloaortic ectasia with or without aortic

valve insufficiency, aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, mitral valve prolapse, and

pulmonary artery dilatation. Musculoskeletal manifestations include scoliosis, chest

wall deformity, arachnodactyly, and acetabular protrusion. Possible central nervous

system manifestations include dural ectasia with or without meningocele. Pneumothorax

and bullae are potential pulmonary manifestations. Ectopia lentis, severe myopia and

retinal detachment may occur. The possible integumentary manifestations include striae

atrophicae and recurrent or incisional hernia.

Imaging is fundamental to diagnose marfan syndrome, to follow-up and to establish a

prognosis. Traditional imaging studies have included:

- echocardiography to evaluate the cardiovascular system

- plain radiography for the skeletal system

- computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging for the aorta and for dural

ectasia. [7].

Young patients with a family history of Marfan syndrome and younger Marfan-like patients

with no family history who present diagnostic criteria by one system should be offered

repeat evaluations, at least at ages 5, 10 and 15 years until age 18 [1]. Imaging alone is

enough for the diagnosis in one quarter of patients.

Images for this section:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-3-320.jpg)

![Page 7 of 44

Findings and procedure details

1-Cardiovascular system:

Cardiovascular system is involved in 90% of death and the most common cause of death

is aortic dissection. [8].

• Annuloaortic ectasia

Progressive sinus enlargement is present in 50 to 60% of adults at the mean age of 35

years with Marfan syndrome, with a greater prevalence in males than in females [9]. It

usually begins with dilatation of the aortic sinuses, which progress into the sinotubular

junction and into the aortic annulus. Fig. 4 on page 14

An aneurysm can be present, it is defined as a localized area of aortic dilatation having

a diameter greater than 50% of the normal diameter [10].

The risk of aortic dissection increases with aortic dilatation, therefore lifetime imaging is

recommended:

- transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is performed at diagnosis to establish aortic

dimensions, ventricular and valvular function, and abnormal aortic compliance. It should

be repeated at 6 months to establish the rate of change of aortic parameters. If there

is significant aortic expansion or if the initial aortic diameter is >4.5 cm, more frequent

imaging is recommended[11].

-CT can be used to evaluate the entire aorta and periaortic structures.As a minimum

measurements include aortic annulus, sinus of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, ascending

and descending diameters at the level of the pulmonary artery.

Sinus of Valsalva is compared to normal values based on age and body surface

area. Normal values for aortic annulus,sinotubular junction, and ascending aorta are

respectively 19mm (range 14-26), 24mm (17-34), and 26mm (21-34).

ECG-gated CT can also assess aortic valve regurgitation on end-systolic images with

triangular coaptation defect [12] Fig. 5 on page 14 .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-7-320.jpg)

![Page 8 of 44

-MRI is not limited by acoustic window and delivers no ionising radiations, and was

validated as ideal for follow-up of patients. ECG-gated end-diastolic black-blood images

using spin echo , SSFP-based cine images and a contrast-enhanced MRA can be

used to assess anatomy and morphology of the aorta. Report has to contain the same

measurements than in CT analysis[8].

• Descending aorta

Dilatation of the descending aorta is another recognized cardiovascular features of

Marfan syndrome, reason why monitoring of the entire aorta is essential for the

management[4, 13].

Descending aorta is considered to be dilated if diameter is over 30mm in the thorax and

24mm in the abdomen[7]. Fig. 6 on page 15

#-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce the systolic ejection and

therefore, the rate of aortic dilatation and dissection.

• Postoperative aspects

Prophylactic surgery is recommended when:

-the diameter of the ascending aorta at the sinus of Valsalva reaches 5 cm or when there

is a rapid dilatation (2mm or 5% a year)

-there is a family history of aortic dissection

-there is a severe aortic valve regurgitation with associated symptoms or progressive

ventricular dilatation or dysfunction [14].

The original operation of aortic root replacement is the Bentall composite graft introduced

in 1968. This includes aortic root and valve replacement with either a biological

or a mechanical valve and requires coronary artery reimplantation . It stays the

standard because of a low rate of reoperation[15] but pose a risk of endocarditis and

thromboembolic disease demanding long-term anticoagulation. Fig. 7 on page 17

Therefore, if the valves cusps are normal, the aortic valve can be implanted into the

vascular graft in a way described by David or can be remodeled into it as in the Yacoub

technique[16].

CT or MRI with SSFP-based cine images can be used for the follow up after prosthetic

replacement. Imaging serves to define post-operative anatomy, to identify haematoma](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-8-320.jpg)

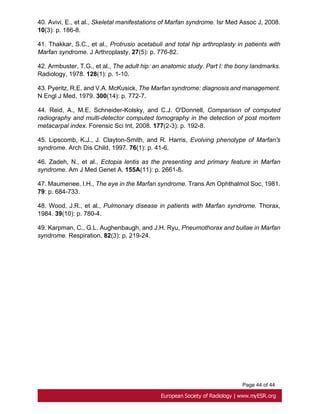

![Page 9 of 44

or leak at proximal and distal graft anastomoses and at coronary reimplantation site [17].

Fig. 8 on page 17, Fig. 9 on page 18, Fig. 10 on page 19

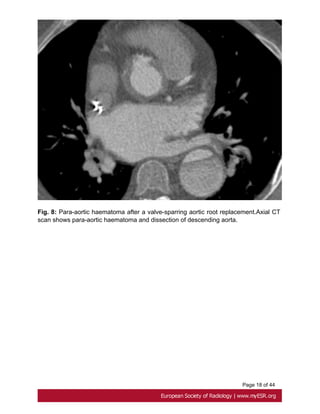

• Aortic dissection

Aortic dissection is characterized by separation of the layers of the aortic media initiated

by a primary intimal tear[10].

Stanford type A dissection, which involves the ascending aorta, should be treated as a

surgical emergency.

Uncomplicated Stanford type B dissection, which is confined to the aortic arch and the

descending aorta, can be treated with medical therapy[18]. Fig. 11 on page 20

ECG-gated CT is the first line investigation in acute dissection. Procedure include a non

contrast study to look for intramural hematoma, and a contrast study. CT shows the false

lumen which is separated from the true lumen by an 'intimal flap", and the extension of

the dissection and any involvement of aortic branch vessels. Fig. 12 on page 21

MRI is recommended for long-term for follow up patients with Stanford B dissection, to

appreciate changes in the size of the dissected aorta .Its use in the acute dissection is

limited by a prolonged study duration [19]. Fig. 13 on page 23

• Bicuspid aortic valve

Prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in Marfan patients is about 5% whereas it is 1-2% in

the general population. A bicuspid valve has two cusps instead of three; most commonly

they are unequal size because of congenital fusion of one of the valves commissures [20].

Bicuspid aortic valve is generally detected by transthoracic echocardiography.

ECG gated and contrast-enhanced CT shows two completely developed cusps and

commissures [21]. Fig. 14 on page 23

• Mitral valve

About 65 % of patients with Marfan's syndrome have mitral valve prolapse. Compared

with myxomatous disease patients, Marfan patients have longer and thinner mitral valve

leaflets, less posterior leaflet prolapsed and more anterior or bileaflet prolapse[22].

• Pulmonary artery](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-9-320.jpg)

![Page 10 of 44

A less common cardiovascular manifestation of Marfan syndrome is dilatation of the main

pulmonary artery. The upper values have been established at 24 mm at the pulmonary

artery bifurcation and 34mm at the pulmonary artery root[23]. Fig. 15 on page 24

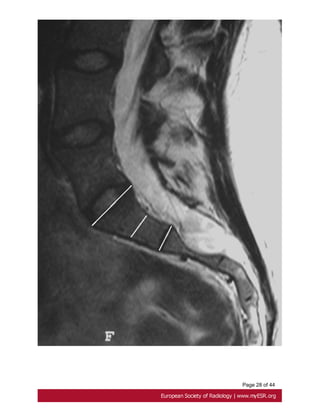

2- Dural ectasia

Dural ectasia (DE) is one of the major criteria of Marfan syndrome in the Ghent nosology.

It has a prevalence in Marfan syndrome of about 60% and its severity increases with

aging[24]. It is a widening of the dural sac or spinal nerve root sleeves, usually associated

with bony erosions of the posterior vertebral body, increased thinning of the cortex of the

pedicles and laminae, widening of the neural foramina, or presence of a meningocele[25].

Ahn Criteria

Ahn et al. described that dural ectasia is present if one major or two minor criteria are

present.

Major criteria:

- width of the dural sac at a level below S1 greater than that above L4. Fig. 16 on page

25

- Presence of an anterior sacral meningocele. It is present when there is a herniation of

the dural sac through a defect in the anterior surface of the sacrum or when the sacral

meninges are herniating anteriorly into the pelvis through a widened foramen[26]. Fig.

17 on page 27

Minor criteria:

-scalloping greater than 3.5 mm at the level of S1. Fig. 18 on page 27

- nerve root sleeve diameter greater than 6.5 mm at the level of L5[27].

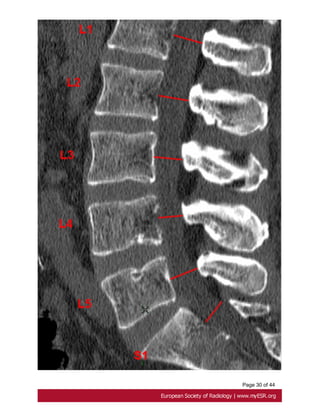

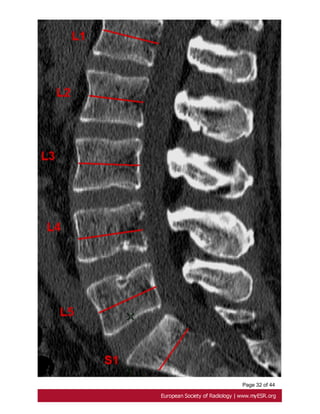

Oosterhof criteria

According to Oosterhof et al, dural sac ratio from levels L1 through S1 in adult patients

have to be greater than respectively 0.64, 0.55, 0.47, 0.48, 0.48, and 0,57 in dural ectasia.

A dural sac ratio is calculated for each level by dividing the sagittal dural sac diameter by

the midsagittal vertebral body diameter [28]. Fig. 19 on page 29, Fig. 20 on page 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-10-320.jpg)

![Page 11 of 44

3- Musculo-skelettal manifestations

The alteration in fibrillin leads to flaccidity in the joint ligaments driving to joint hy-

permobility and reduction in the control of bone growth[29].

• Scoliosis

Scoliosis affects around 62% of Marfan patients. In Marfan patients, there is a higher

prevalence of double thoracic and triple major curves[30], and sagittal alignment is more

often hyperkyphotic[31].

Conventional X-ray with anterioposterior and lateral radiography of the entire spine are

used for measuring the Cobb angle. Scoliosis over 20° is a major Ghent criterion[7].

Reformatted CT scan shows the progressive deformation of the thoraco-lumbar

vertebrae, with loss of the normal vertebral concavity, progressive antero-lateral growth

reduction, vertebral flattening, and development of marginal osteophytes which suggest

secondary spinal arthritis[32]. Fig. 21 on page 33

MR imaging looks for abnormalities of the spinal cord and the nerve roots.

Brace treatment is the initial management in children with moderate scoliosis, while the

definitive treatment is arthrodesis for most progressive curves of more than 40°[33].

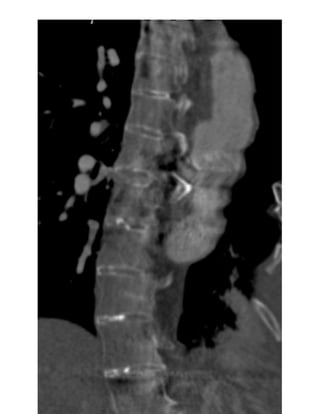

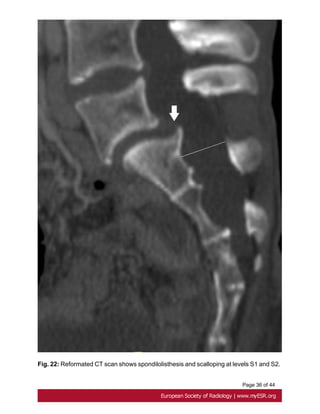

• Spondylolisthesis

Analysis of the Marfan lumbar spine found a higher prevalence of spondylolisthesis,

corresponding to the displacement of a vertebra in relation to the vertebrae [5]below[30].

Fig. 22 on page 35

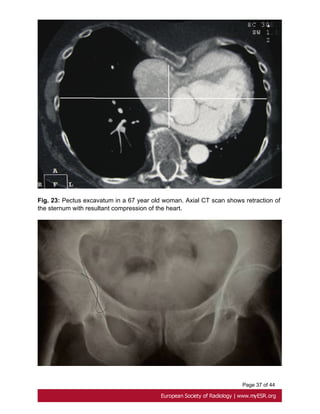

• Pectus deformities

-Pectus excavatum is present in two thirds of patients with Marfan syndrome although

the incidence in general population is between 1 in 400 and 1 in 1000 births[34]. It results

from the displacement of the sternum and costosternal joints.

Pectus excavatum is considered severe if Haller index is above 3.25, which is the

ratio between the lateral distance of the chest wall at inner margins and the narrowest

anteroposterior distance between the vertebrae and sternum [35]. Fig. 23 on page 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-11-320.jpg)

![Page 12 of 44

CT scanning is commonly used for this purpose but MRI and even standard radiographs,

with anteroposterior and lateral incidences, have a high diagnostic accuracy. [36, 37].

- Pectus carinatum, an anterior protrusion of the upper portion of the sternum, does not

narrow the anterioposterior diameter of the chest and therefore does not displace the

heart. It is usually repaired for cosmetic reason[38].

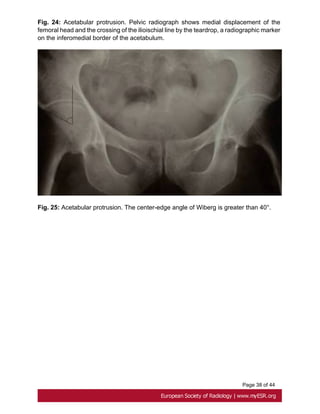

• Acetabular Protrusion

Intrapelvic acetabular protrusion is a deformity of the hip joint in which the medial wall

of the acetabulum invades the pelvic cavity with associated medial displacement of the

femoral head [39]. Progressive protrusion can lead to early osteoarthritis by a loss of

posteroinferior joint space[40].

Acetabular protrusion can be assessed with three methods on pelvic radiographs:

- the crossing of the ilioischial line by the teardrop, a radiographic marker on the

inferomedial border of the acetabulum just superior to the obturator foramen [40]. Fig.

24 on page 37

-the center-edge angle of Wiberg : an angle between a vertical line drawn through the

center of the femoral head and another line drawn from the center of the femoral head

through the lateral margin of the acetabulum is greater than or equal 40° Fig. 25 on page

38

-the acetabular-ilioischial distance is greater than or equal to 3 mm in men and greater

than or equal to 6 mm in women (method of Armbuster)[41, 42].

Treatment of this abnormality comprises both conservative ( weight extension on an

abduction frame and reeducation) and surgical methods.

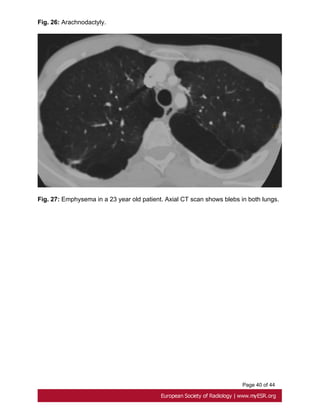

• Arachnodactyly

Arachnodactyly is a very common characteristic of Marfan syndrome.

The metacarpal index is calculated by the average central length of the second to fifth

metacarpals divided by the average narrowest widths of the second to fifth metacarpals.

An index greater than 8,4 is considered abnormal [12, 44]. Fig. 26 on page 38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-12-320.jpg)

![Page 13 of 44

The Steinberg thumb sign test consists of requesting the patient to perform an adduction

of the thumb and flexion of fingers and the test is considered positive when the distal

phalanx of the thumb surpassed the palmar area[43].

The Walker-Murdoch wrist test can also be used. Patients are requested to hold the wrist

with the contralateral hand and it is considered positive when the little finger and thumb

overlap.

• Dolichostenomelia

A positive dolichostenomelia is determined as a value of arm span on height index less

or equal to 1.05 [29].

• Flat feet

"Pes planovalgus" or flat feet is frequently associated with joint hypermobility which most

common symptom is a tendency for the ankle to turn over easily[45].

4-Ocular manifestations

• Ectopia lentis

Ectopia lentis is the most common ocular abnormality in MFS in which there is

displacement of the lens, and the ciliary zonular filaments are stretched or discontinuous

with disrupted microfibrills. Lenses tend to be bilaterally dislocated upward[46].

• Retinal detachement

Other ocular manifestations include retinal detachement which complicates high myopia

and increased axial length of the globe [47].

5-Pulmonary manifestations

• Emphysema

It is relatively more frequent in Marfan patients than in the general population. Pulmonary

elastic fiber changes result from cyclical tissue stresses in tissue lacking mechanical

support.[48]. Fig. 27 on page 40

• Spontaneous pneumothorax](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-13-320.jpg)

![Page 14 of 44

The prevalence of spontaneous pneumothorax is higher in Marfan patients and is

reported to be 4 to 11%. It has been suggested that blebs and bullae have no

predictive value for recurrence in patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax and

that peripheral airway obstruction with airtrapping may be the main mechanism for

pneumothorax [48, 49].

Images for this section:

Fig. 4: Annuloaortic ectasia in a 23-year-old man. Reformatted CT image shows marked

dilatation of the Valsalva sinus and the sinotubular junction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-14-320.jpg)

![Page 42 of 44

11. Baumgartner, H., et al., ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital

heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J. 31(23): p. 2915-57.

12. Ha, H.I., et al., Imaging of Marfan syndrome: multisystemic manifestations.

Radiographics, 2007. 27(4): p. 989-1004.

13. Engelfriet, P.M., et al., Beyond the root: dilatation of the distal aorta in Marfan's

syndrome. Heart, 2006. 92(9): p. 1238-43.

14. Akin, I., et al., Current role of endovascular therapy in Marfan patients with previous

aortic surgery. Vasc Health Risk Manag, 2008. 4(1): p. 59-66.

15. Aomi, S., et al., Aortic root replacement using composite valve graft in patients with

aortic valve disease and aneurysm of the ascending aorta: twenty years' experience of

late results. Artif Organs, 2002. 26(5): p. 467-73.

16. Bechtel, J.F., et al., [Reconstructive surgery of the aortic valve: the Ross, David, and

Yacoub procedures]. Herz, 2006. 31(5): p. 413-22.

17. Mesana, T.G., et al., Late complications after prosthetic replacement of the ascending

aorta: what did we learn from routine magnetic resonance imaging follow-up? Eur J

Cardiothorac Surg, 2000. 18(3): p. 313-20.

18. Ueda, T., et al., A pictorial review of acute aortic syndrome: discriminating and

overlapping features as revealed by ECG-gated multidetector-row CT angiography.

Insights Imaging. 3(6): p. 561-71.

19. Listijono, D.R. and J.R. Pepper, Current imaging techniques and potential biomarkers

in the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection. JRSM Short Rep. 3(11): p. 76.

20. Bennett, C.J., J.J. Maleszewski, and P.A. Araoz, CT and MR imaging of the aortic

valve: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 32(5): p. 1399-420.

21. Glockner, J.F., D.L. Johnston, and K.P. McGee, Evaluation of cardiac valvular

disease with MR imaging: qualitative and quantitative techniques. Radiographics, 2003.

23(1): p. e9.

22. Bhudia, S.K., et al., Mitral valve surgery in the adult Marfan syndrome patient. Ann

Thorac Surg, 2006. 81(3): p. 843-8.

23. Nollen, G.J. and B.J. Mulder, What is new in the Marfan syndrome? Int J Cardiol,

2004. 97 Suppl 1: p. 103-8.

24. Ahn, N.U., et al., Dural ectasia and conventional radiography in the Marfan

lumbosacral spine. Skeletal Radiol, 2001. 30(6): p. 338-45.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/marfansecr-180805163526/85/Marfans-ecr-42-320.jpg)