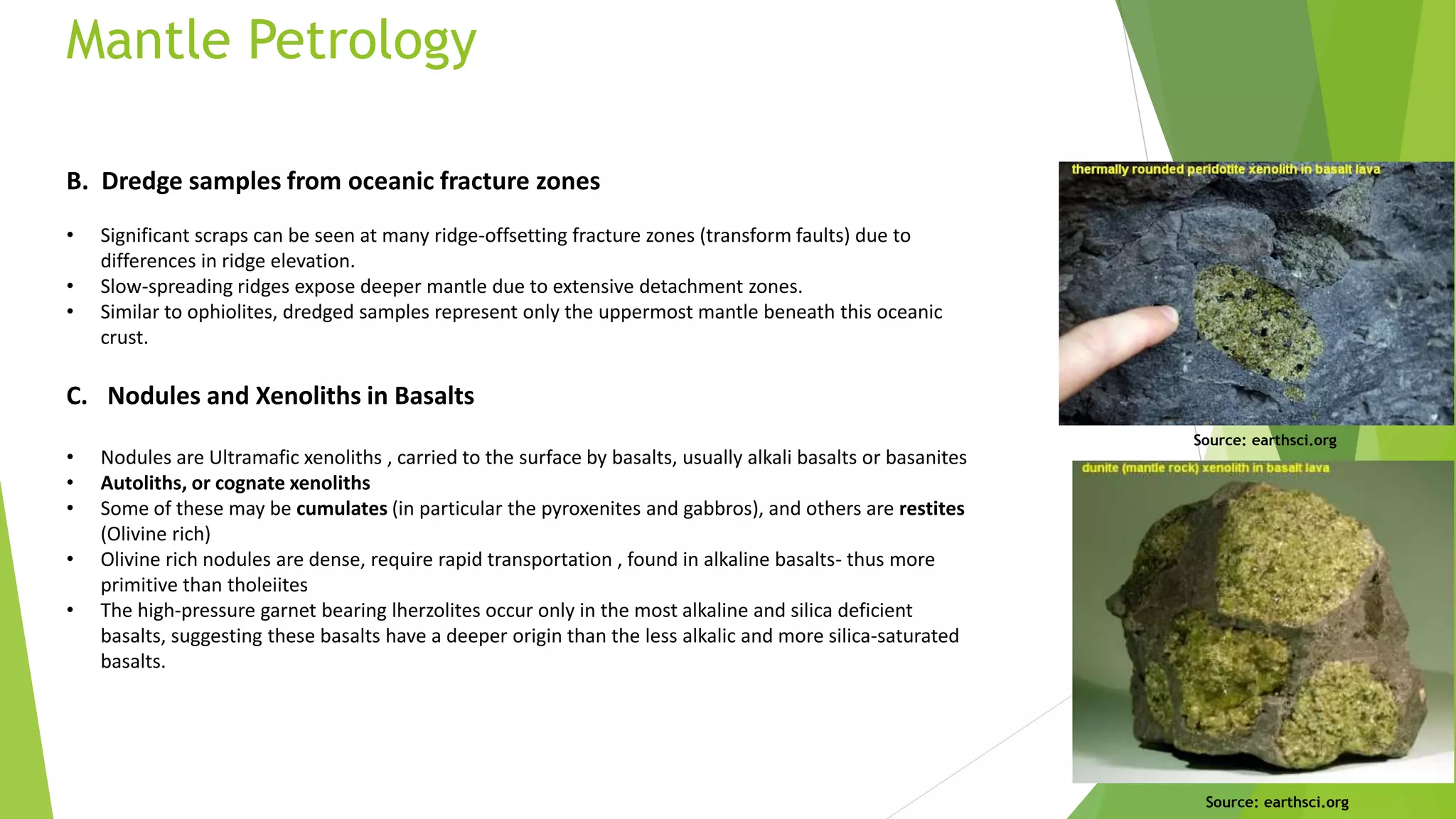

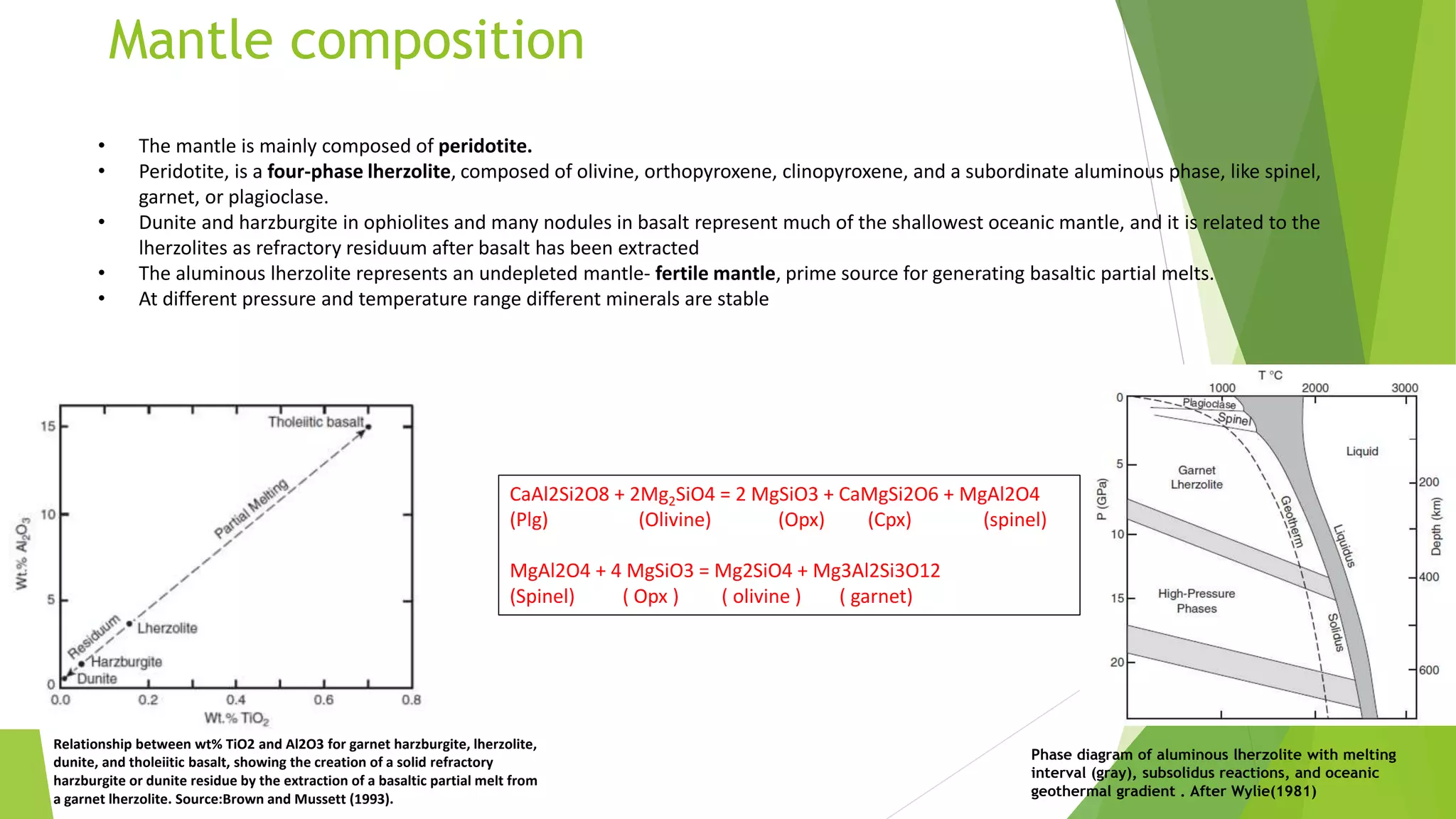

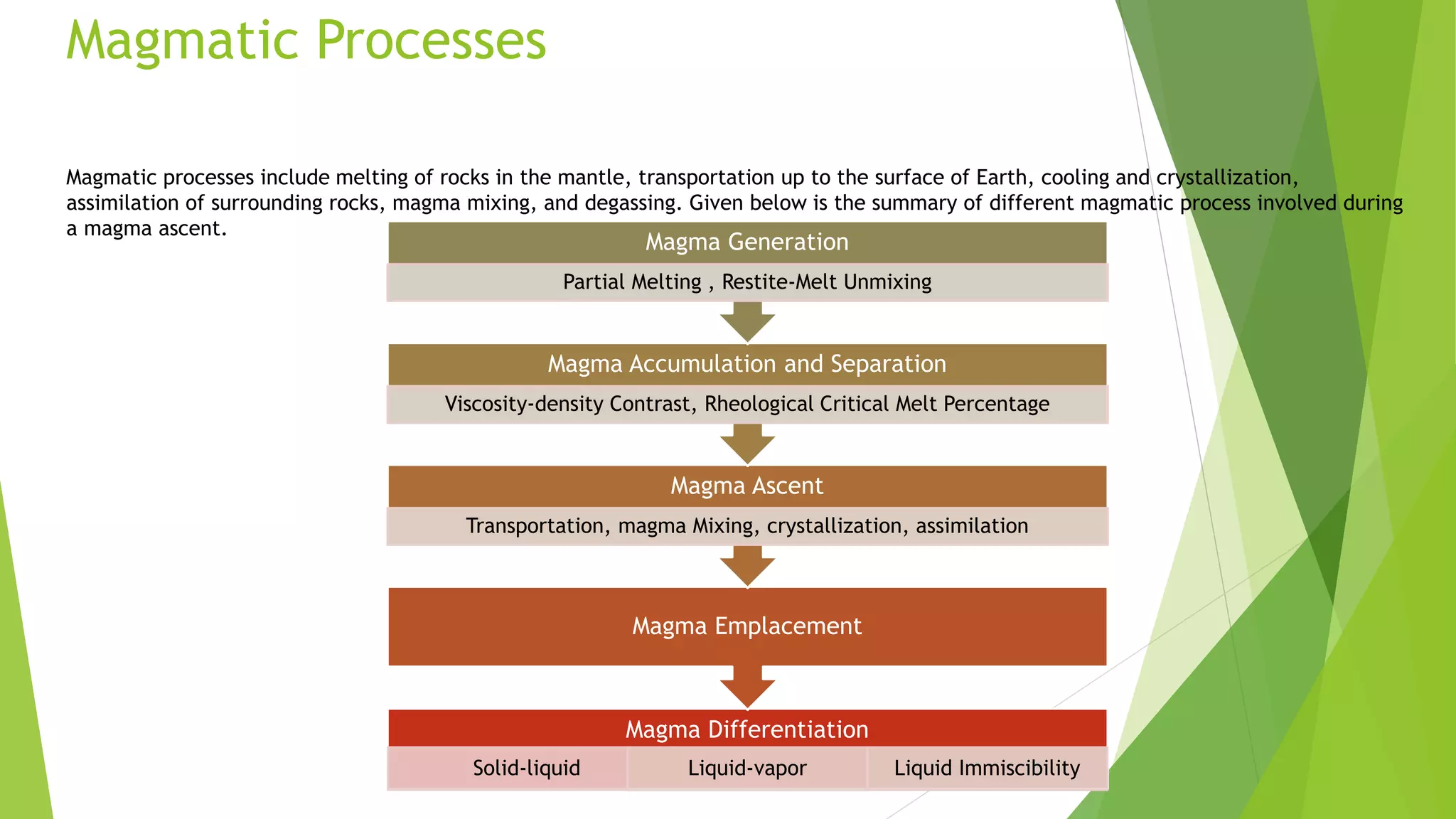

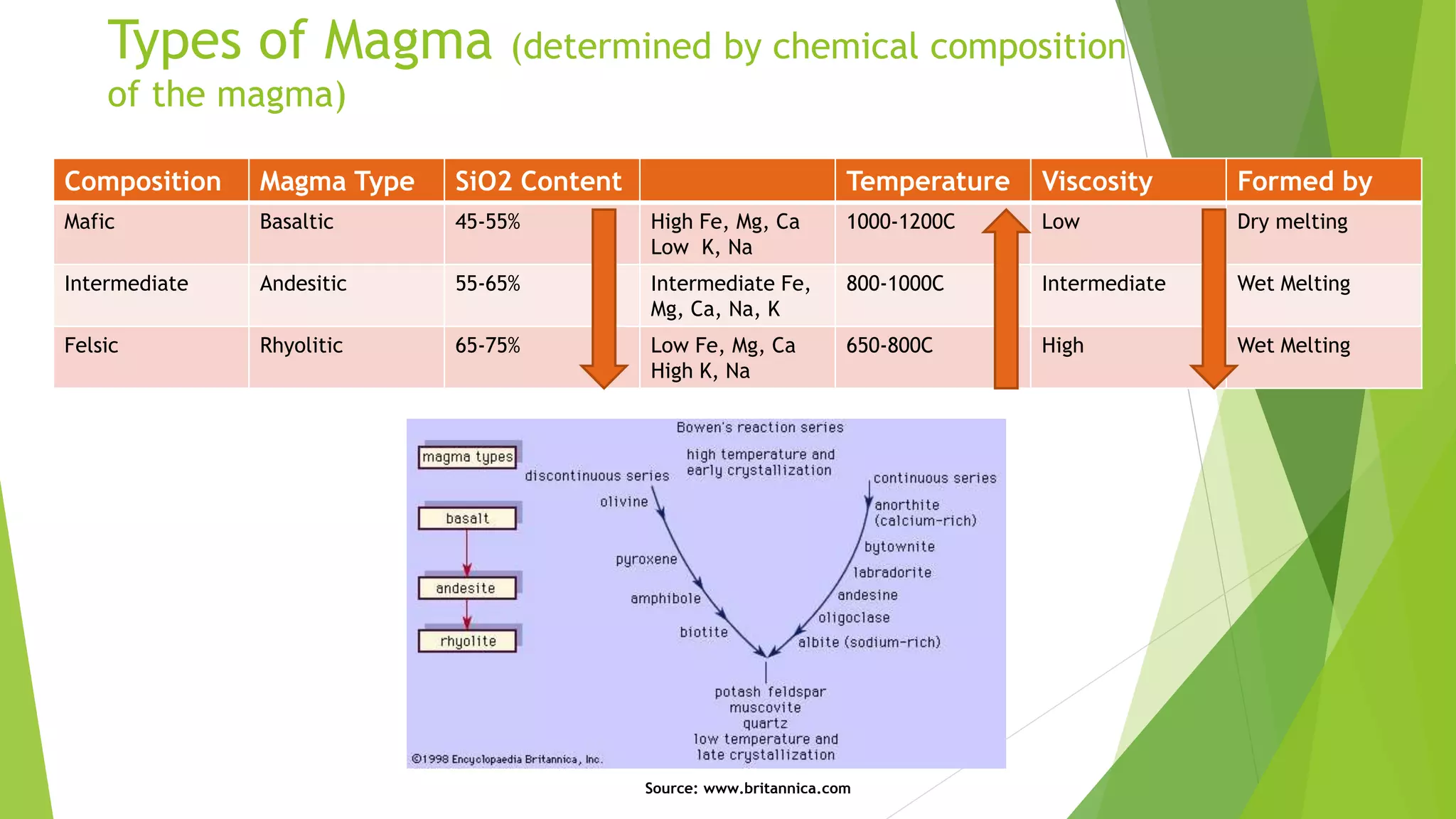

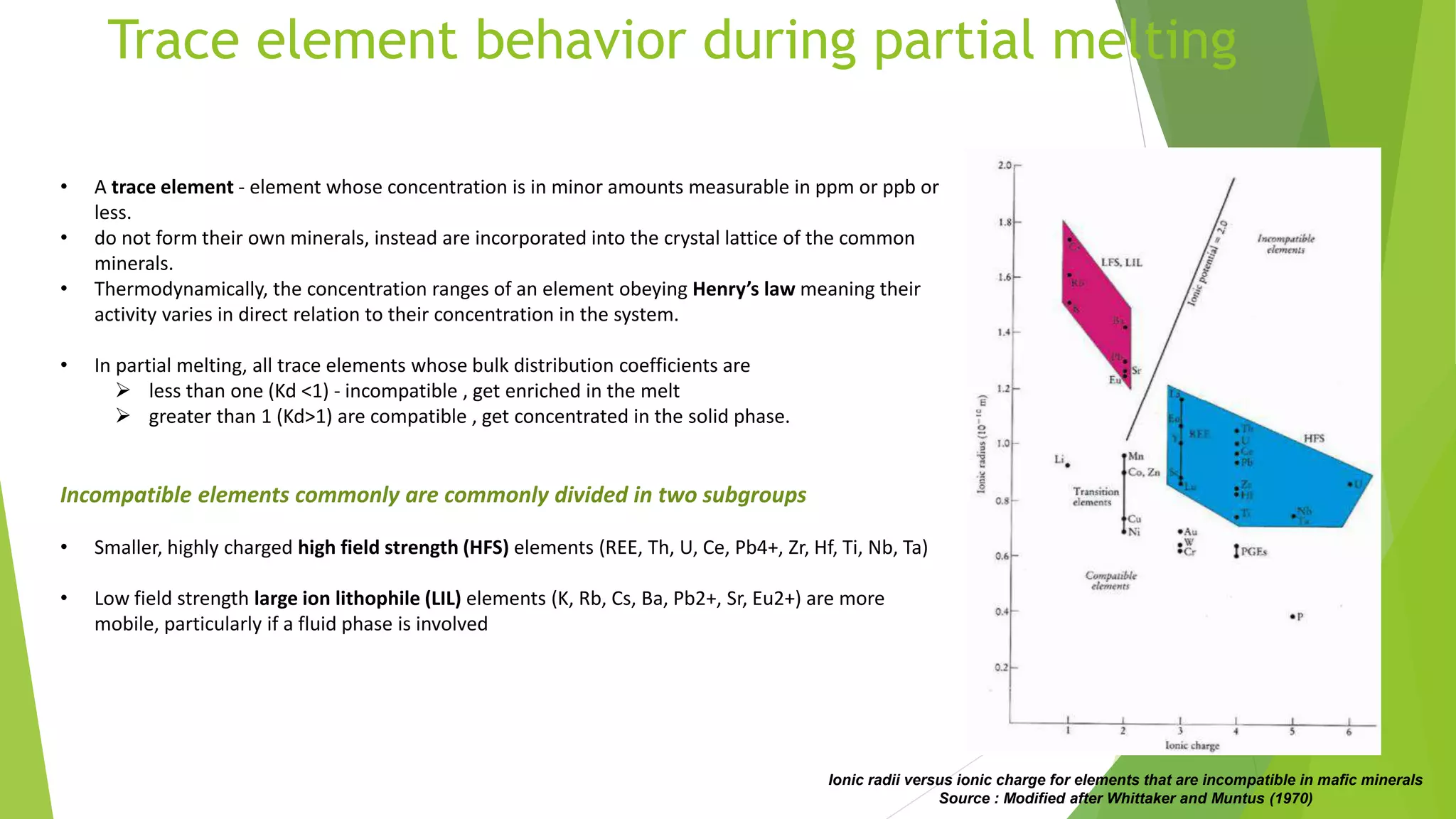

This document discusses mantle melting and magmatic processes. It begins by describing the composition and petrology of the mantle, obtained from samples such as ophiolites, dredged rocks, and mantle xenoliths. Mantle melting can occur through heat-induced melting, adiabatic decompression melting, or flux melting through the addition of volatiles. Magmatic processes include partial melting, magma accumulation and separation, mixing, emplacement, and differentiation during solidification. Magmas are classified based on their composition into mafic, intermediate, and felsic types. Trace elements are enriched or depleted during partial melting depending on their bulk distribution coefficients. Models of magma evolution include batch and fractional melting.

![Models of Magma Evolution

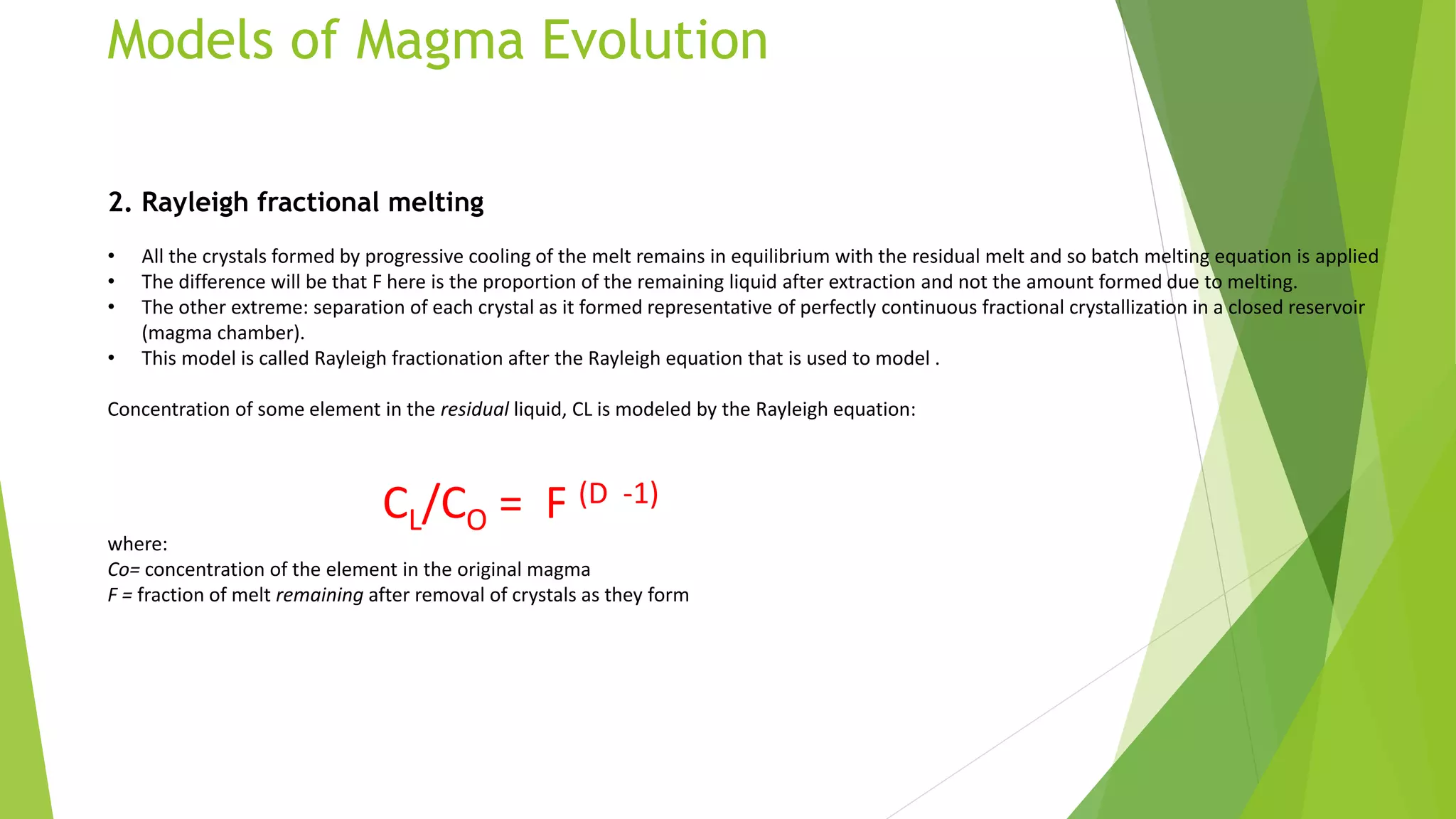

1. Batch Melting:

• It is the simplest model for equilibrium process that involve solid and liquid.

• The melt remains resident (in equilibrium) until at some point it is released and moves upward from

the residue as independent system.

• So it is Equilibrium melting process with variable % melting

• Equation to model batch melting derived by Shaw (1970):

Where:

Co = original concentration of the trace element

F = weight fraction of melt produced [ melt/(melt + rock)]

3 possible cases

• When D<1 (Highly incomaptib)

• When D>1 (Compatible )

• As F->1 , CL/CO = 1 Variation in the relative concentration of a trace element in a

liquid versus source rock as a function of and the

fraction melted

C

C

1

Di (1 F) F

L

O

=

- +](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mantlemelting-211126053709/75/Mantle-melting-and-Magmatic-processes-16-2048.jpg)