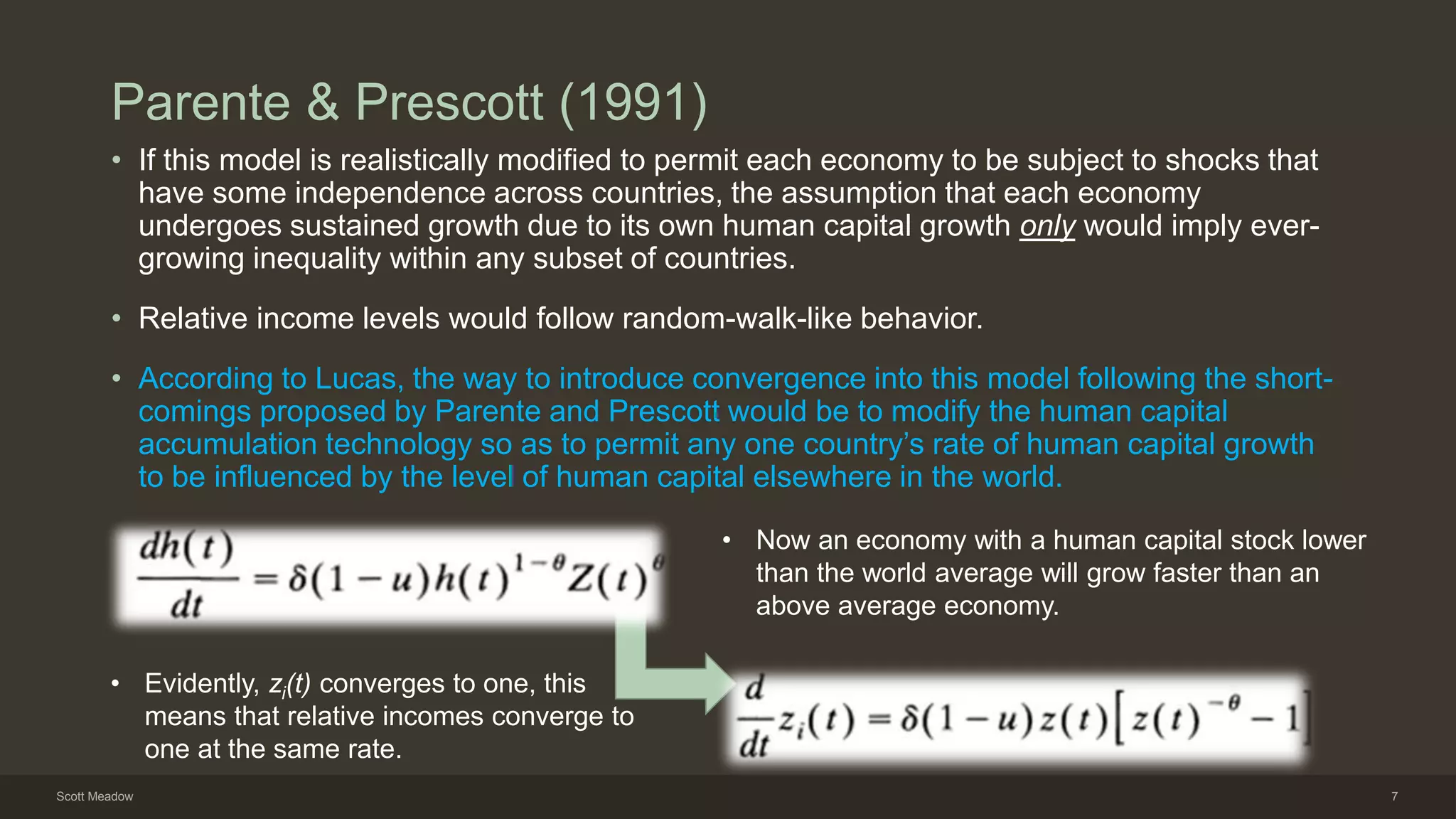

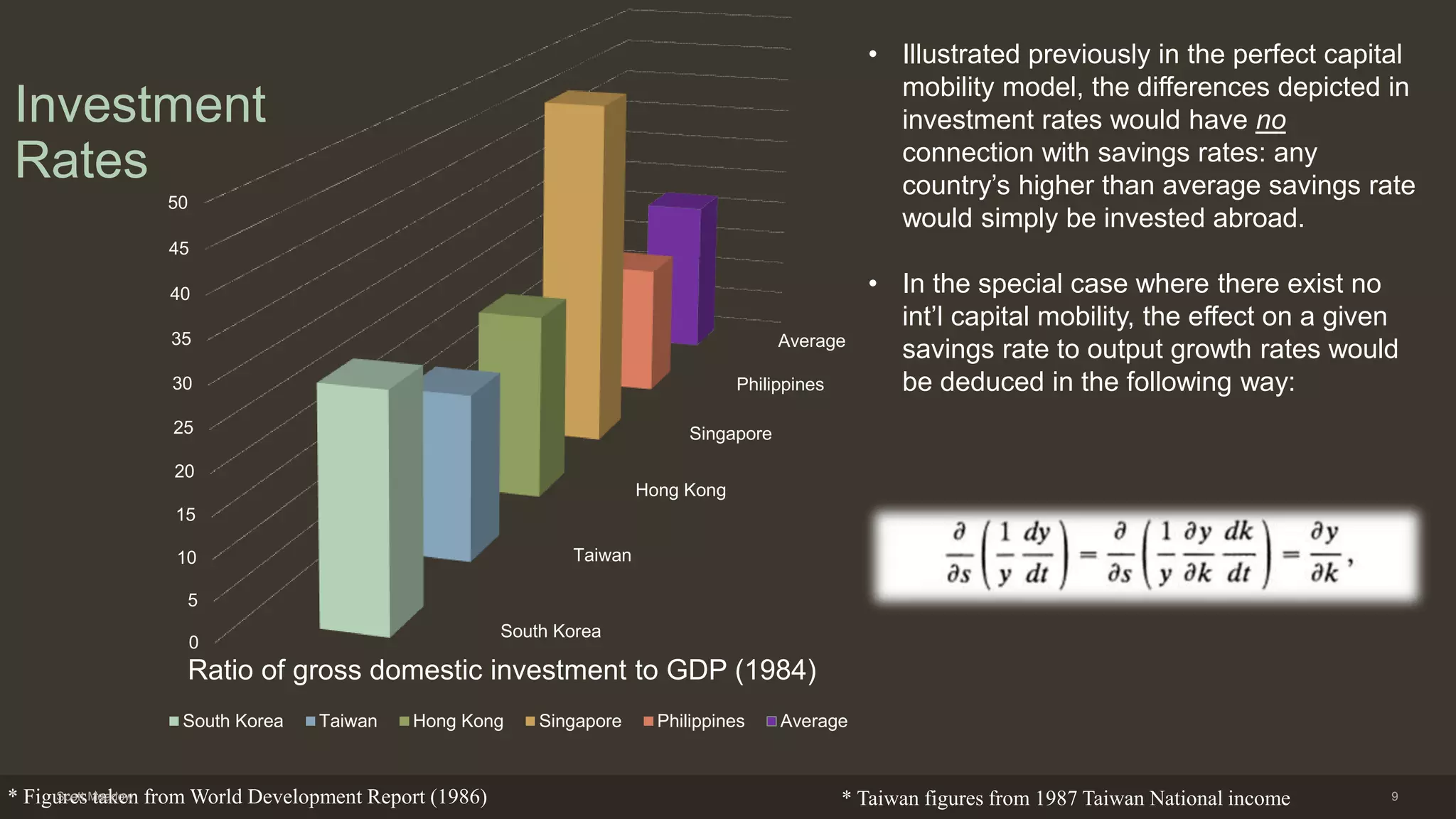

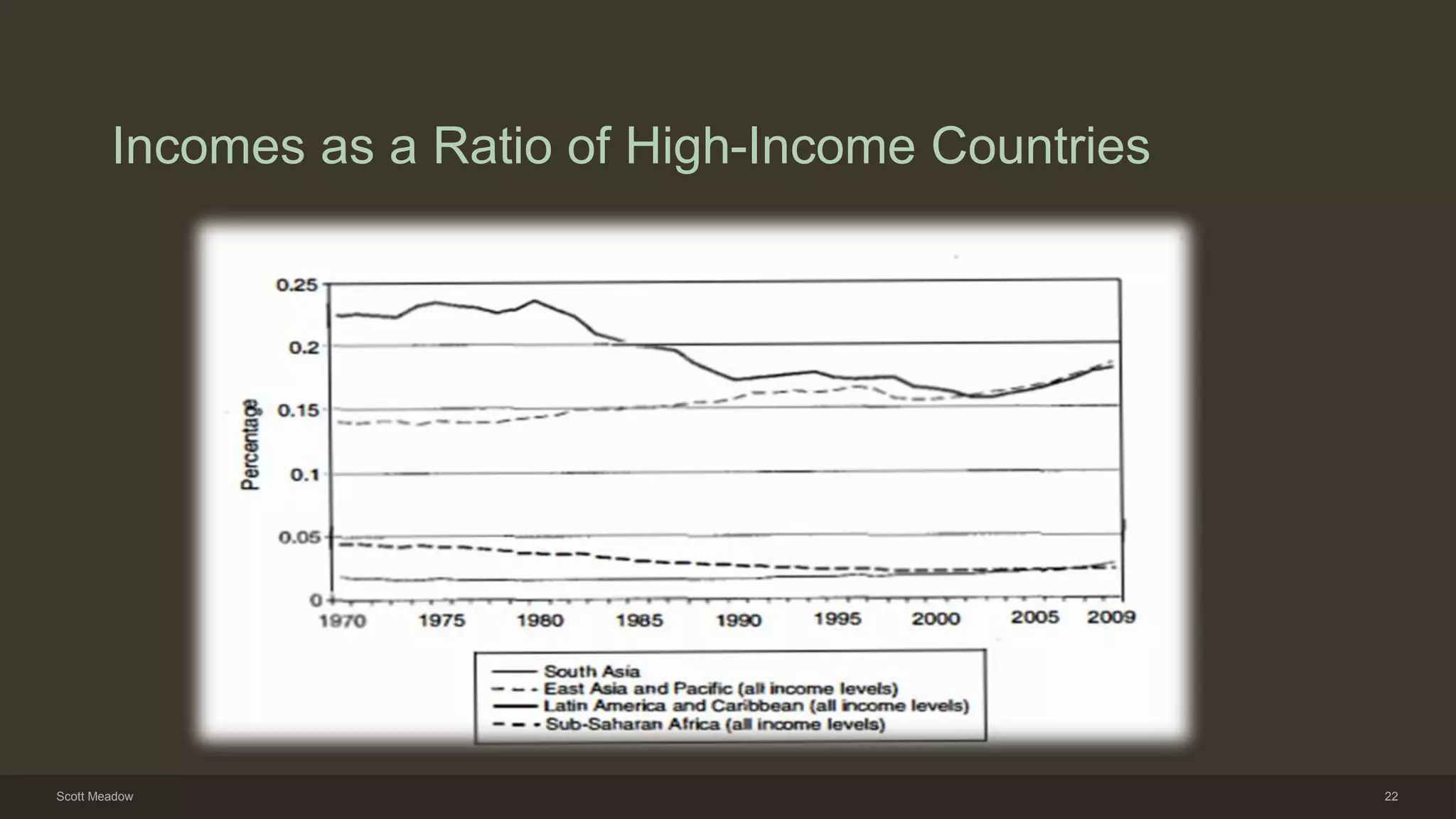

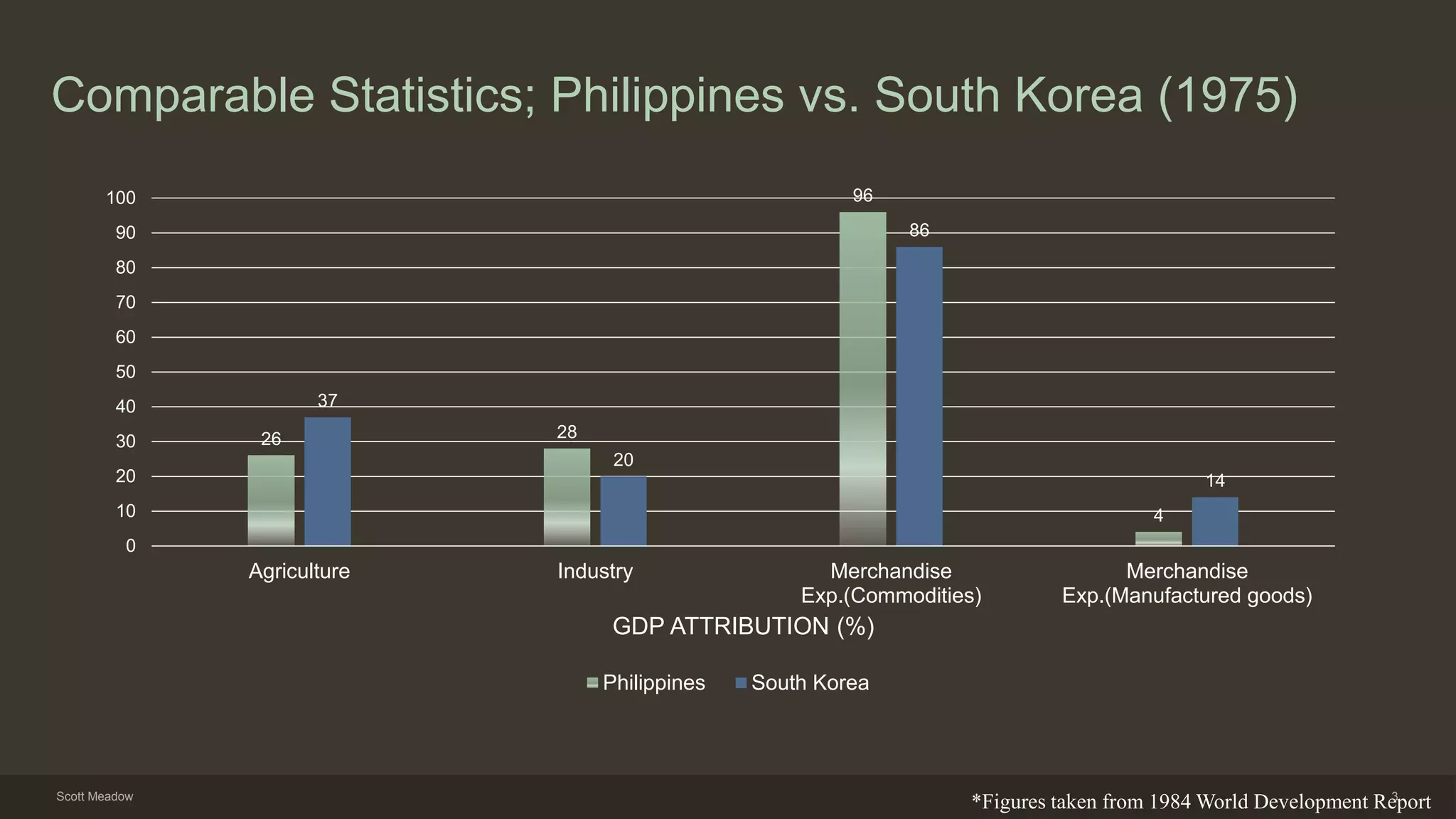

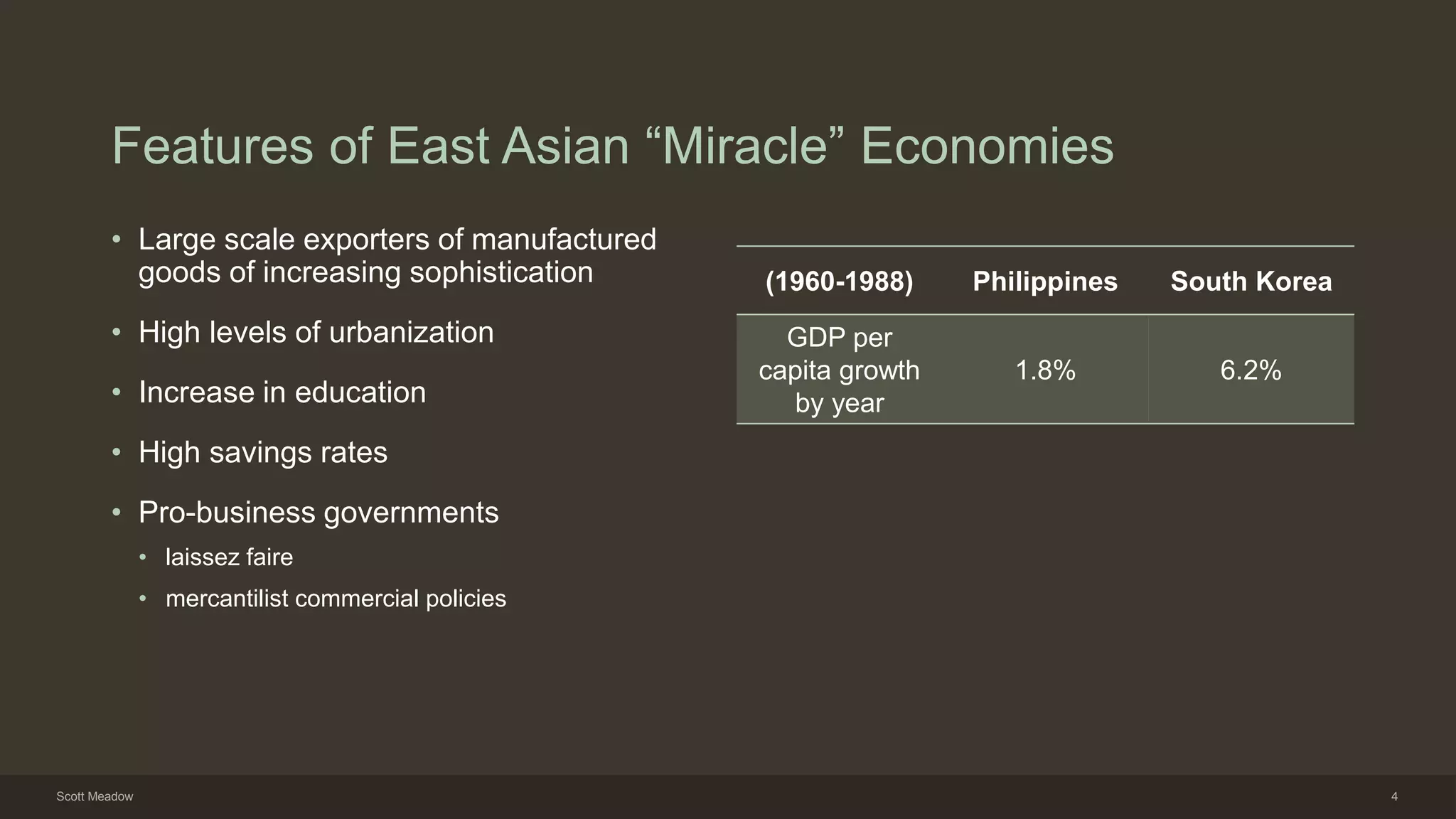

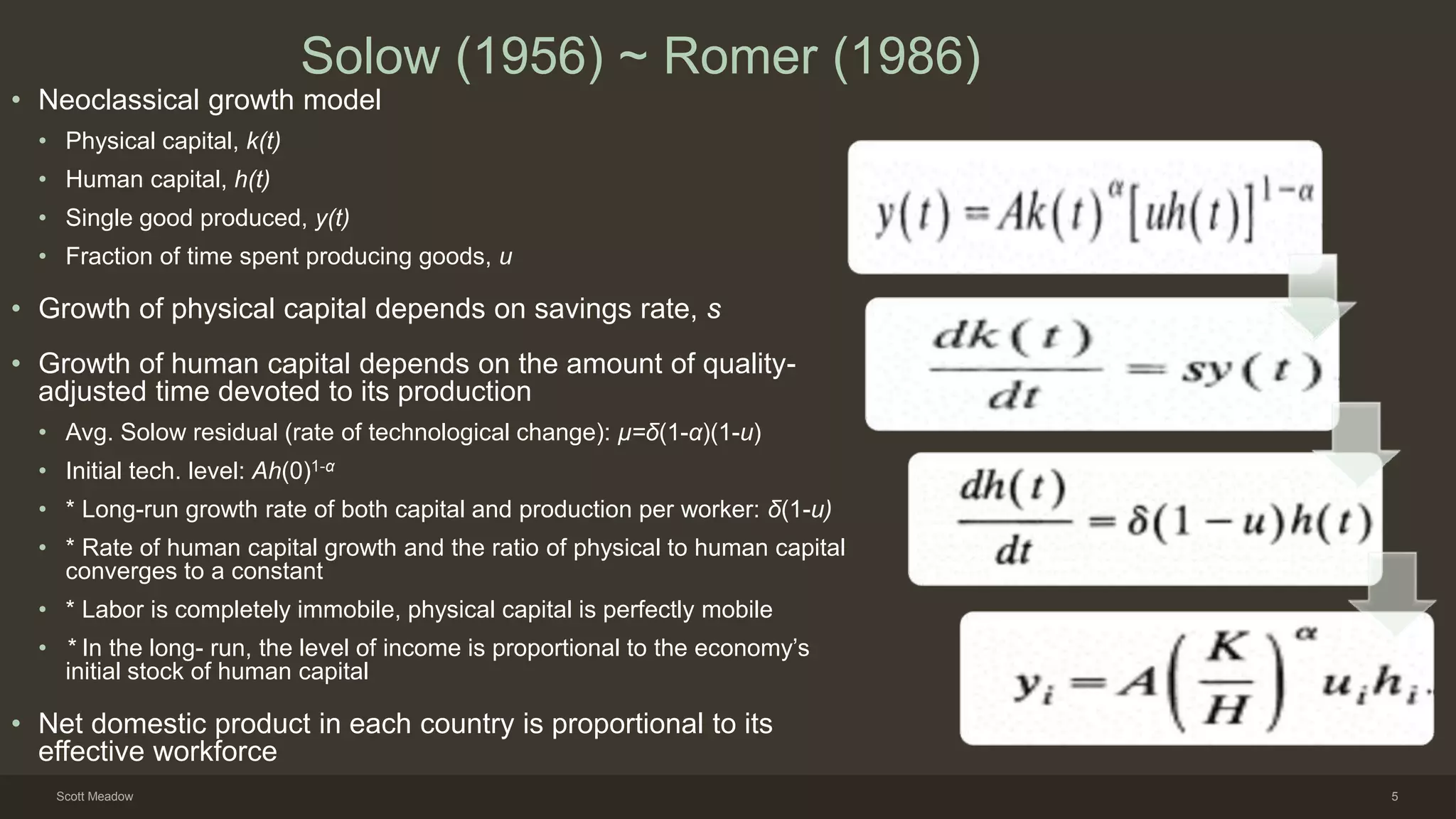

Lucas summarizes several economic theories and models of economic growth, including neoclassical theories focusing on productivity, technology, and human capital accumulation. He compares statistics of the Philippines and South Korea in 1975, noting South Korea's higher investment in industry and manufactured goods. Key features of East Asian "miracle" economies are discussed. Lucas then summarizes Solow and Romer's neoclassical growth models and their assumptions. He discusses several challenges to these models by Parente and Prescott, Barro and Sala-i-Martin, and others. Lucas concludes that differences in human capital accumulation, particularly through learning on the job, best explain differences in growth rates between countries.

![Solow (1956) ~ Romer (1986) [Assumptions]

• If each county has the technology with a common intercept A, this world return is,

r = αA(K/H)α-1

where H = Σiuihi is the world supply of effective labor devoted to goods production.

• If everyone has the same constant savings rate s, the dynamics of this world economy are

essentially the same as those of Solow’s model.

• The world capital stock follows (dK/ dt) = sAKαH1-α , and the time path of H is obtained by summing the savings rate

of goods production over countries, each multiplied by its own time allocation variable ui

• The long run growth rate of physical capital and of every country’s output is equal to the growth rate of human

capital, not only in the long run but all along the equilibrium path.

• * (The theory is thus consistent with the permanent maintenance of any degree of income inequality.)

• This ultimately implies that the reinterpretation of Solow's technology variable as a country-specific

stock of human capital, a model that predicts rapid convergence to common income levels is

converted into one that sis consistent with permanent income inequality.

• The key assumption on which this prediction is based- that human capital accumulation in any one

economy is independent of the level of human capital in other economies- conflicts with the evidence

fact that ideas developed in one place spread elsewhere, that there is one frontier of human

knowledge, not one for each separate economy.

Scott Meadow 6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/makingamiracle-scottmeadow-150416200535-conversion-gate01/75/Making-a-Miracle-6-2048.jpg)