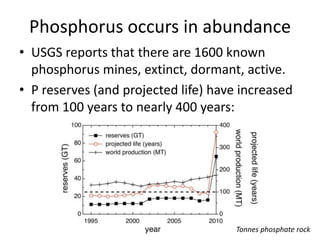

The document discusses the importance of mineral resources like phosphorus and potash for food security and economic growth. It notes that while phosphorus reserves are large, improved sustainability is needed. Potash production needs to double to meet global demand. Fertilizer minerals present a challenge to ensure affordable access for growing populations, particularly in Africa. More research is needed to develop alternatives if conventional fertilizers become inaccessible.