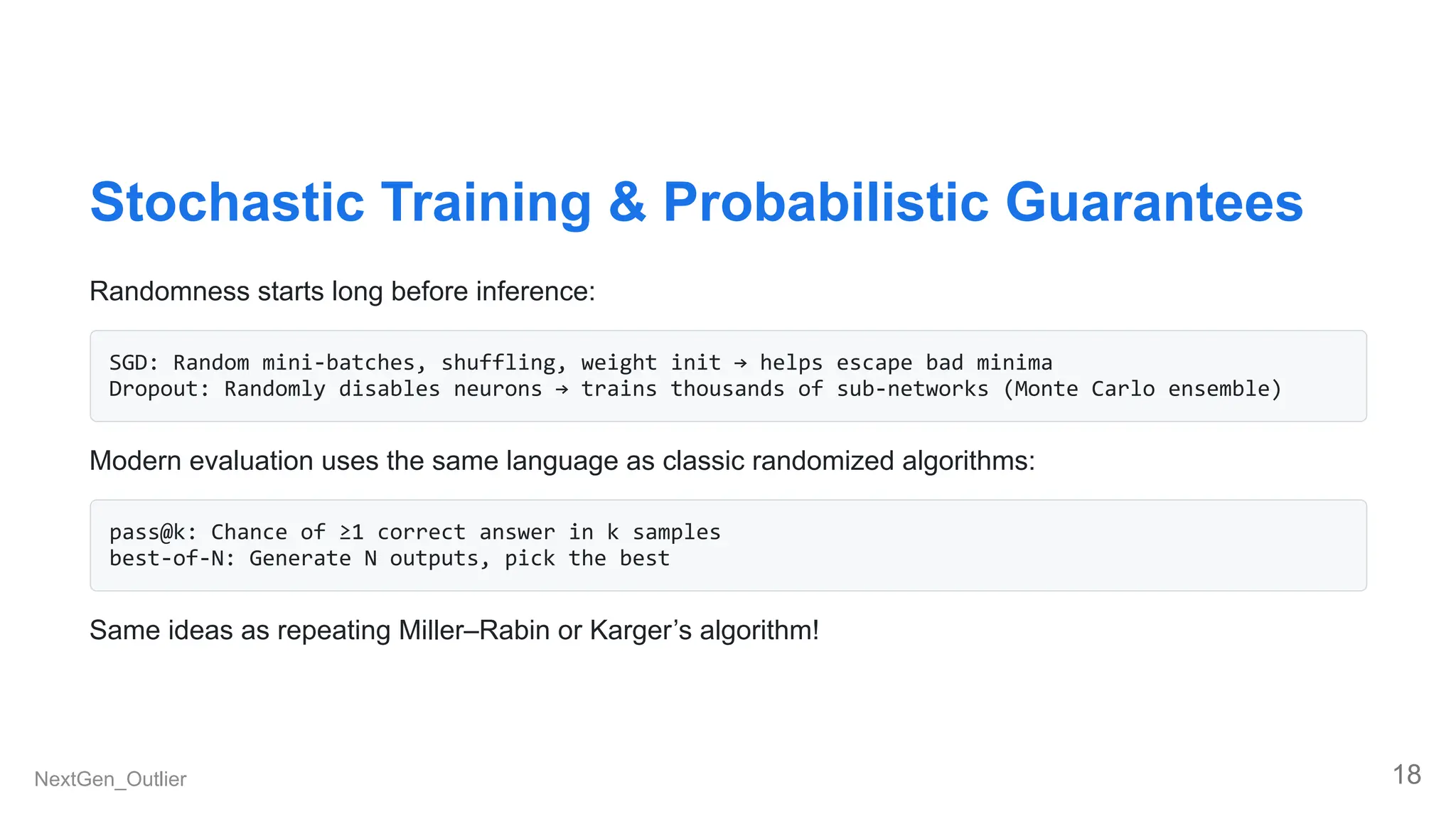

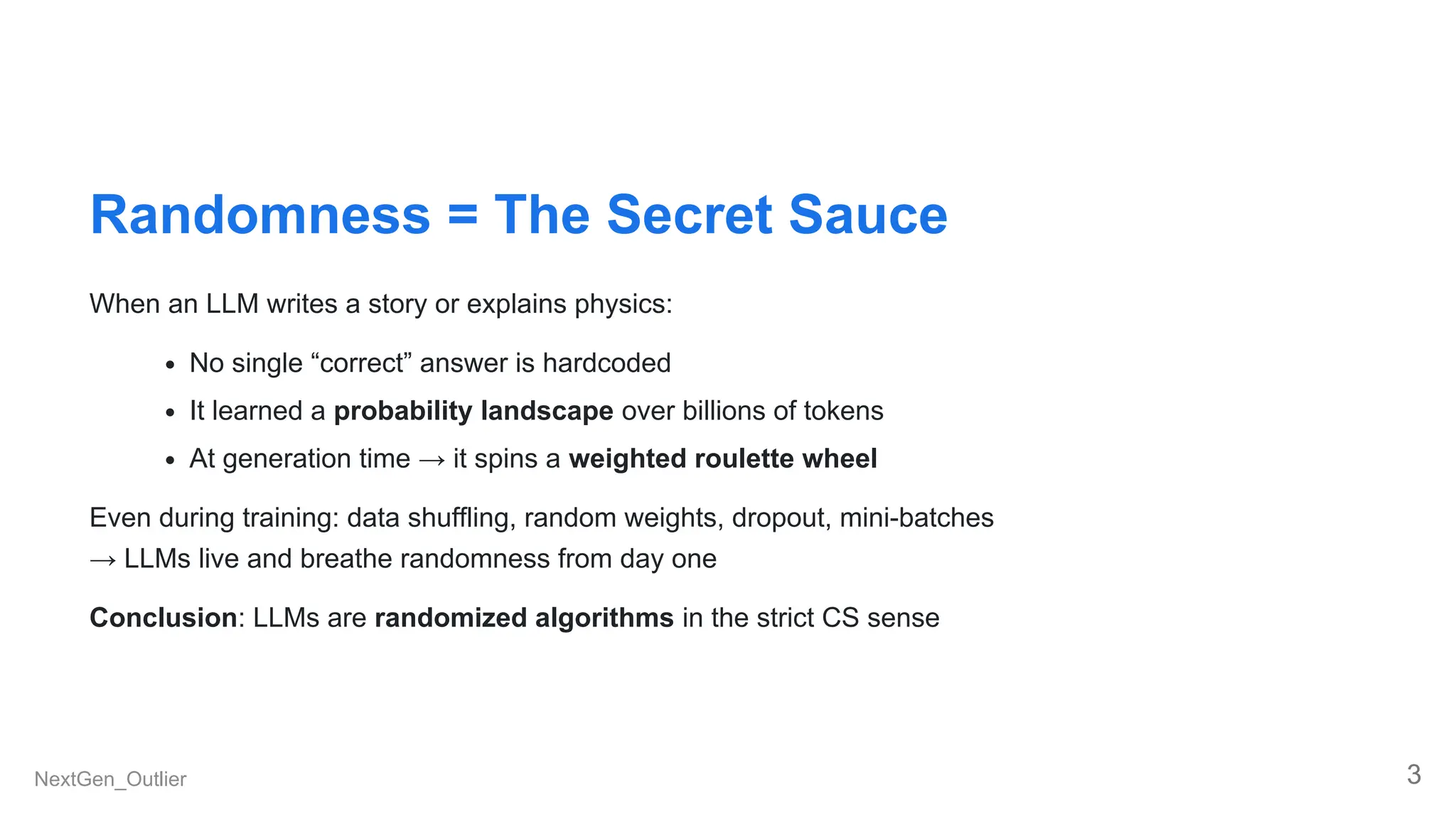

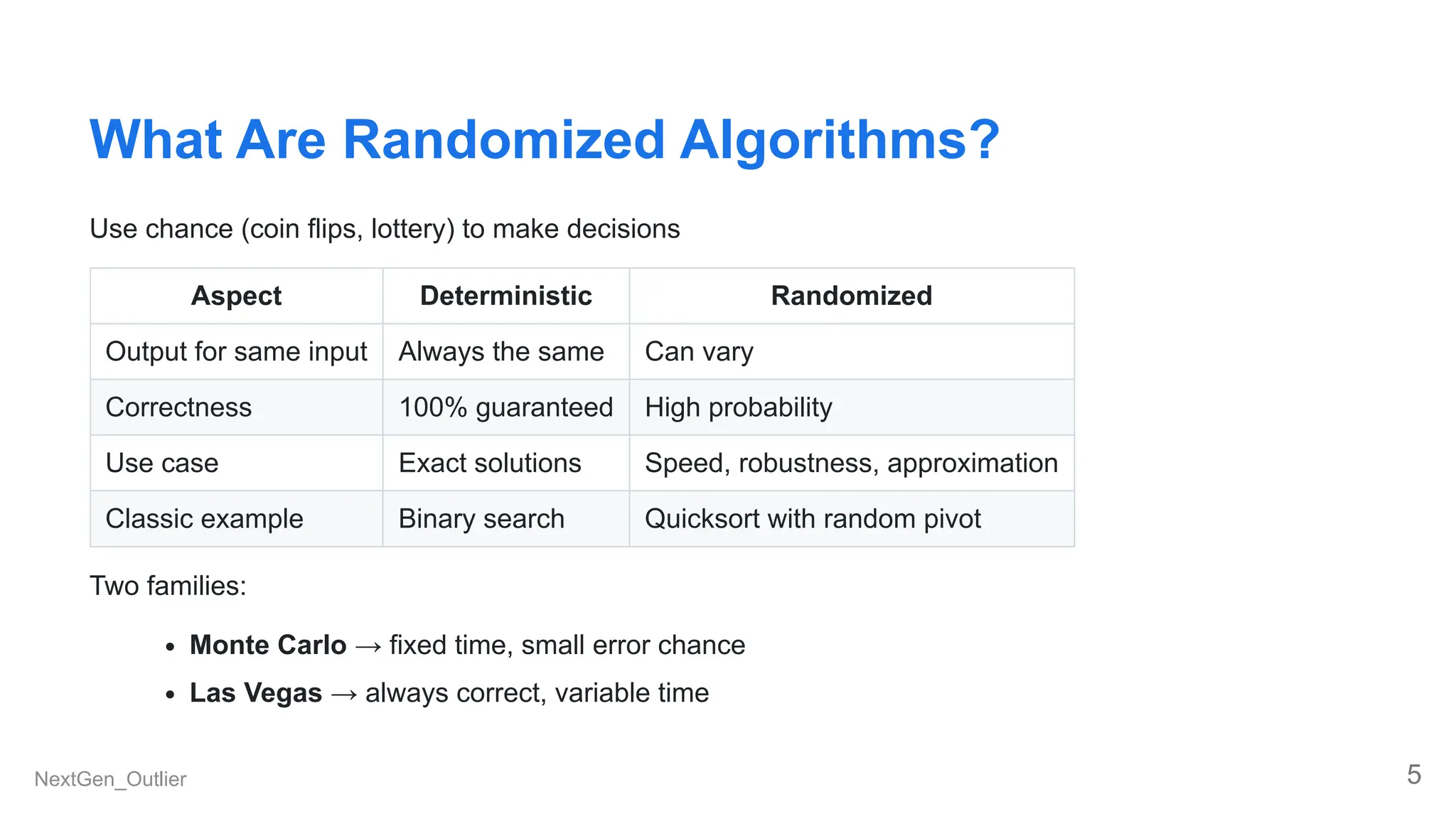

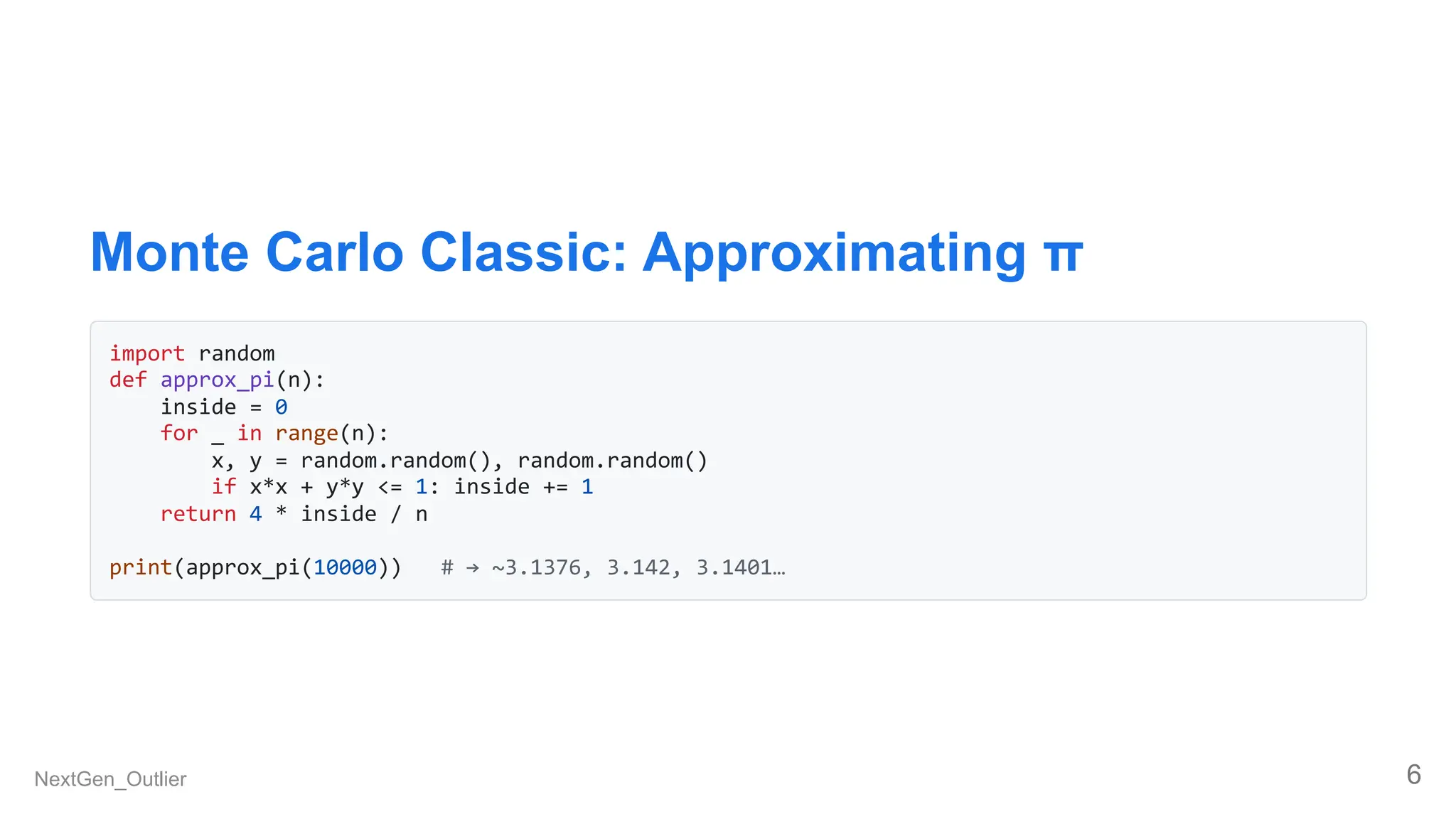

Many people perceive the varying responses from ChatGPT, Claude, or Grok as bugs. However, these variations are intentional, mathematically grounded features that stem from decades of randomized algorithm design, including concepts like Monte Carlo, Las Vegas, quicksort pivots, Miller-Rabin, dropout, and adversarial robustness.

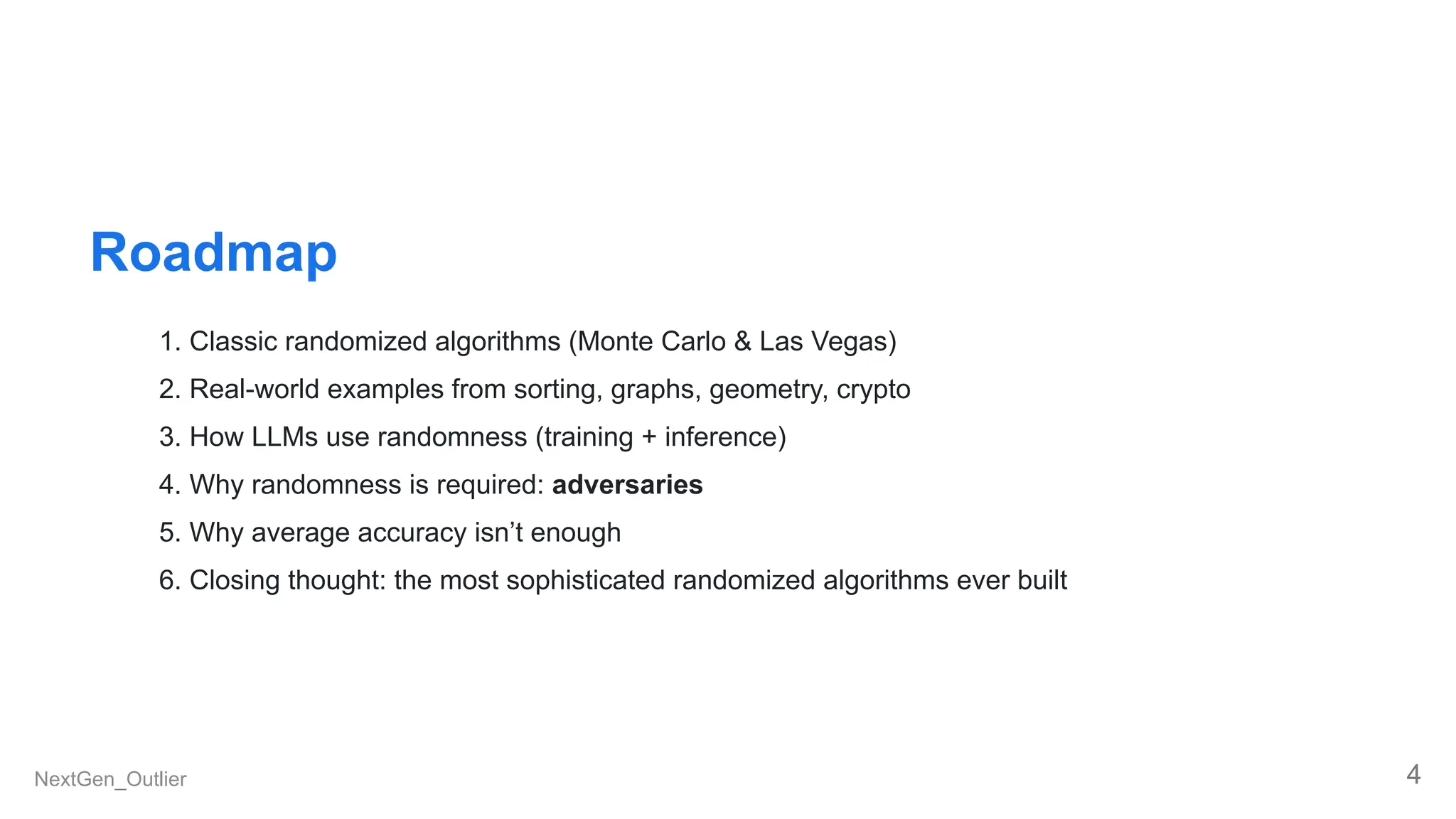

If you've ever wondered about the following:

- Why LLMs change their mind on the same prompt

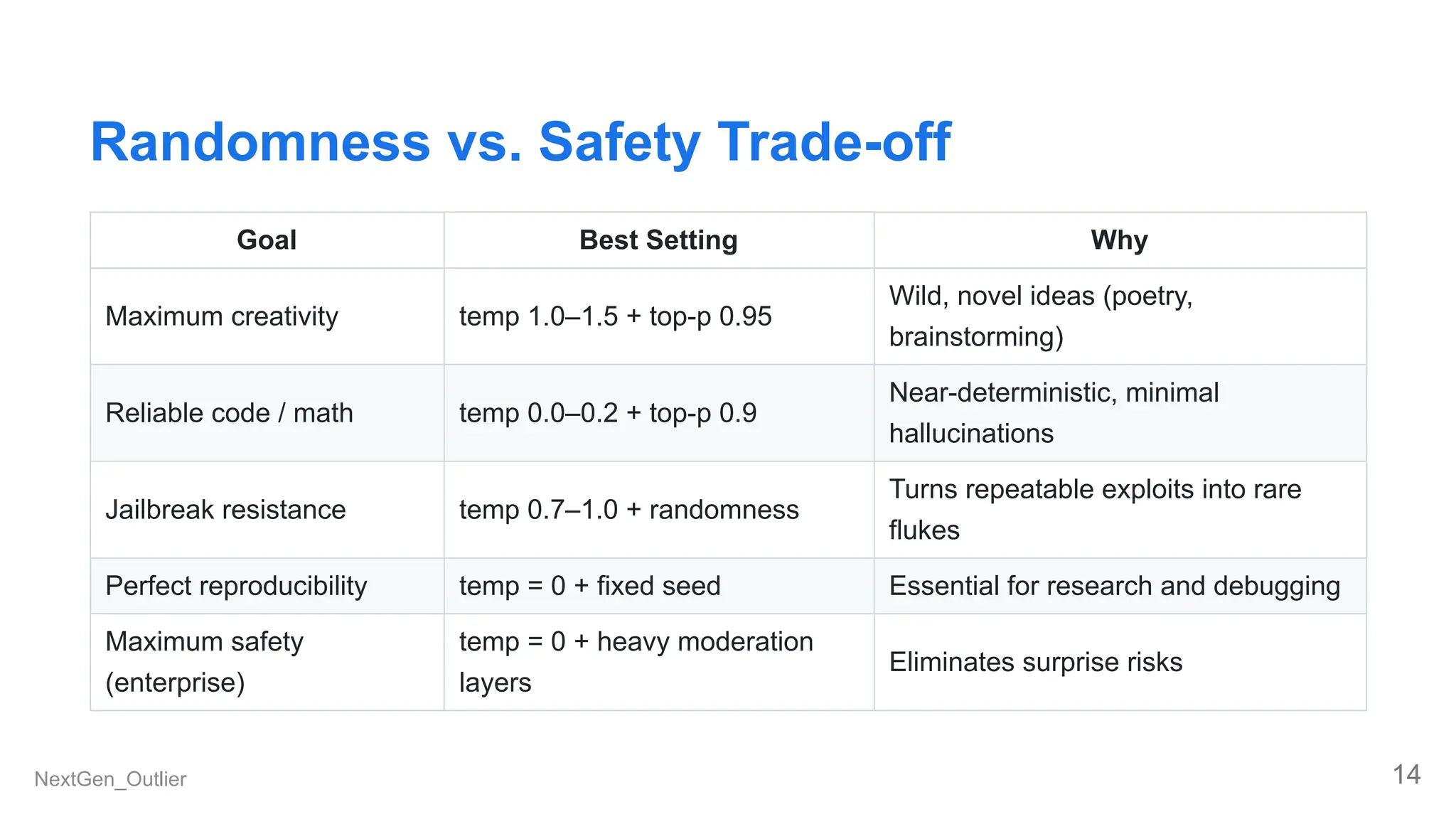

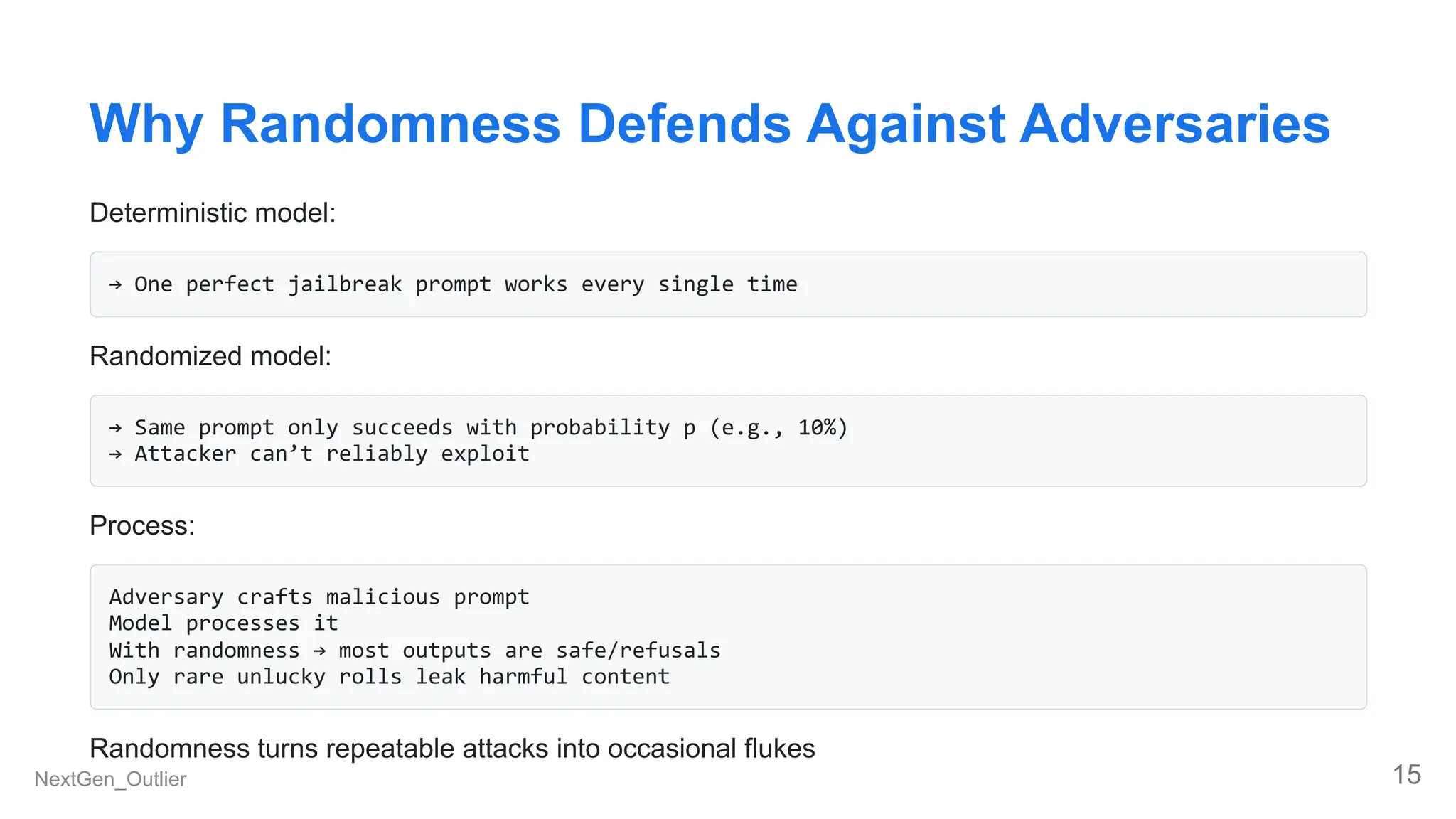

- Why a temperature setting greater than 0 can sometimes be the safest choice

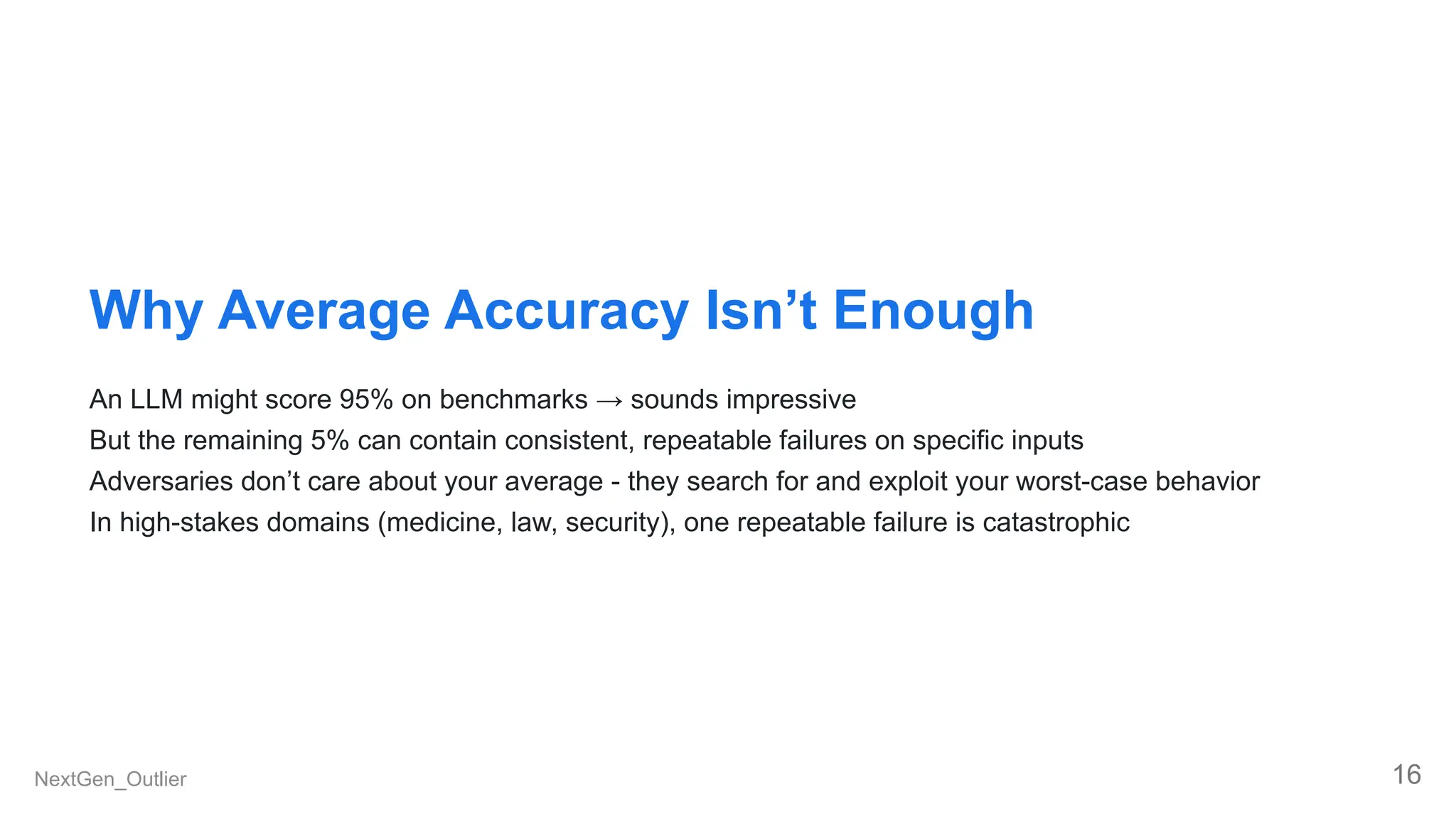

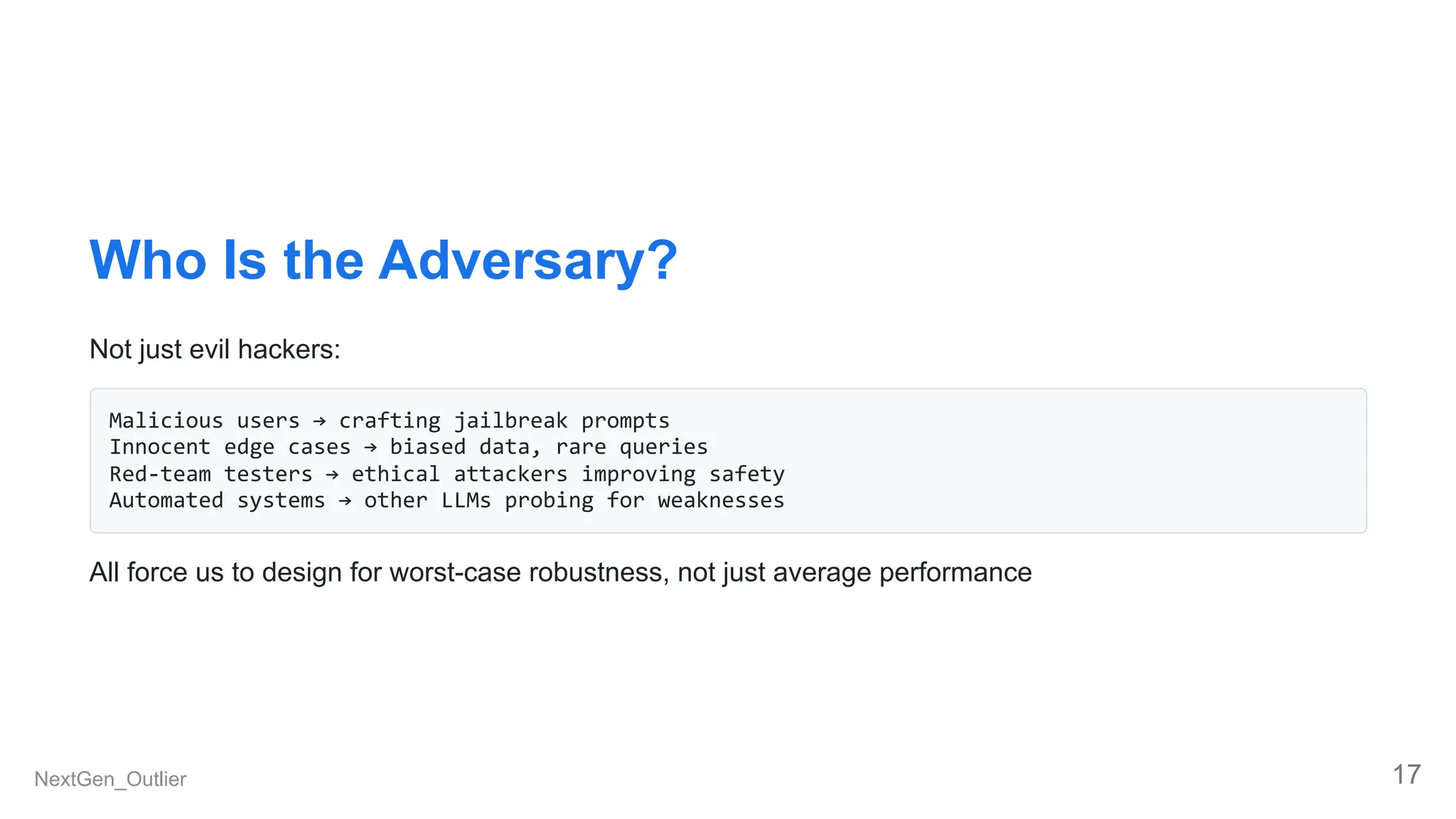

- Why an average accuracy of 95% is insufficient when facing adversaries

This discussion is for you.

https://lnkd.in/eztWcawe

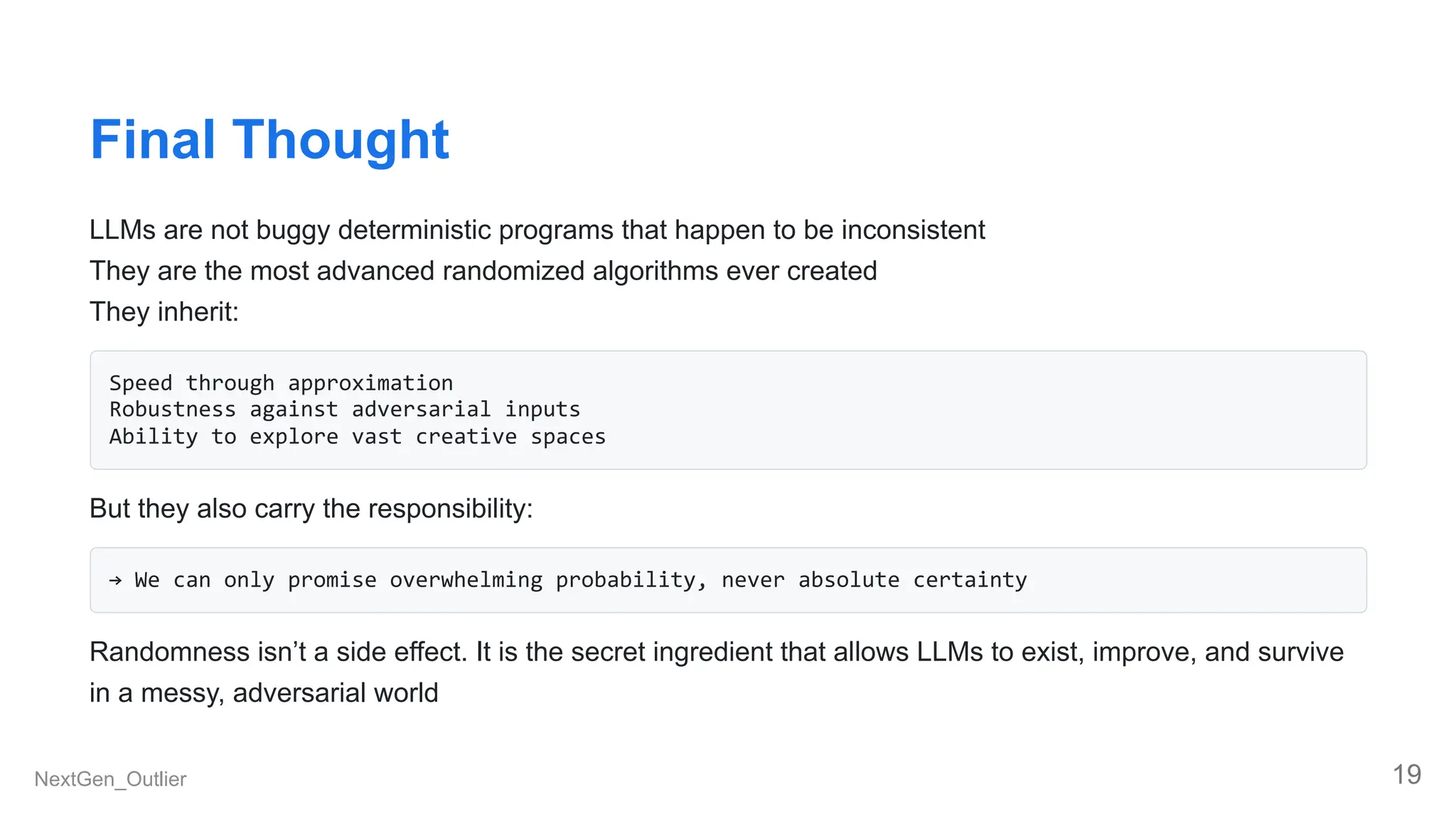

![LLMs Have a Curious Habit

Ask the exact same question twice → you might get two different answers

Traditional programs are deterministic:

2 + 2 → always 4

sort([3,1,4,1,5]) → always [1,1,3,4,5]

LLMs behave differently on purpose

→ This unpredictability is not a bug — it is a feature built on randomness

NextGen_Outlier 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/llmsrandomize-251212104826-9d40be47/75/LLMs_Randomize-Are-Large-Language-Models-Actually-Randomized-Algorithms-2-2048.jpg)

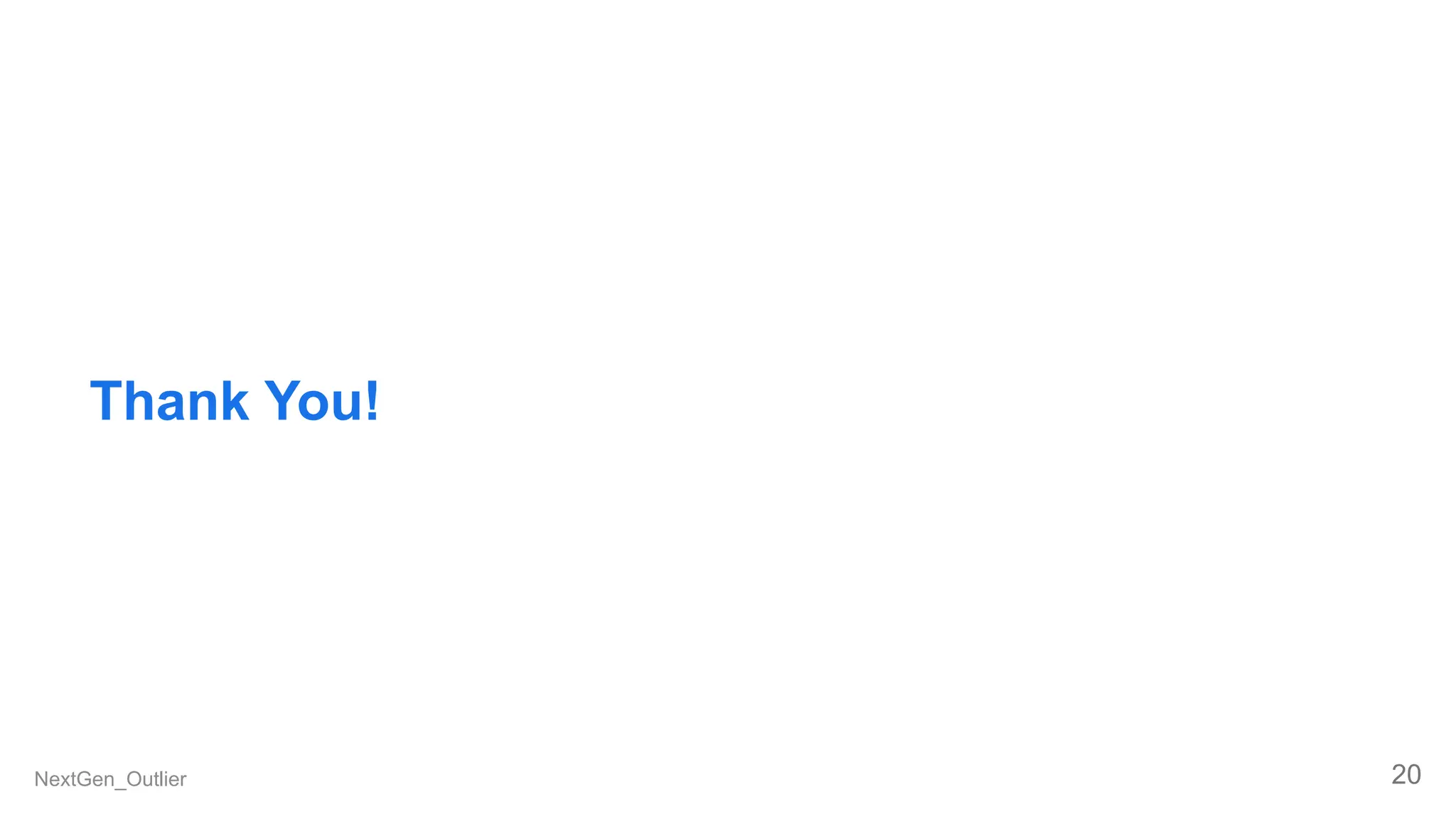

![Las Vegas Classic: BogoSort (the worst &

funniest)

import random

def is_sorted(arr):

return all(arr[i] <= arr[i+1] for i in range(len(arr)-1))

def bogosort(arr):

while not is_sorted(arr):

random.shuffle(arr)

return arr

# Warning: Expected time O(n!) only use on tiny lists!

How it works:

Keep shuffling the array completely at random.

After each shuffle, check if it's sorted.

Stop only when it is (which might take forever).

Pure Las Vegas: always correct, but time varies wildly. Perfectly illustrates the trade-off.

NextGen_Outlier 8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/llmsrandomize-251212104826-9d40be47/75/LLMs_Randomize-Are-Large-Language-Models-Actually-Randomized-Algorithms-8-2048.jpg)

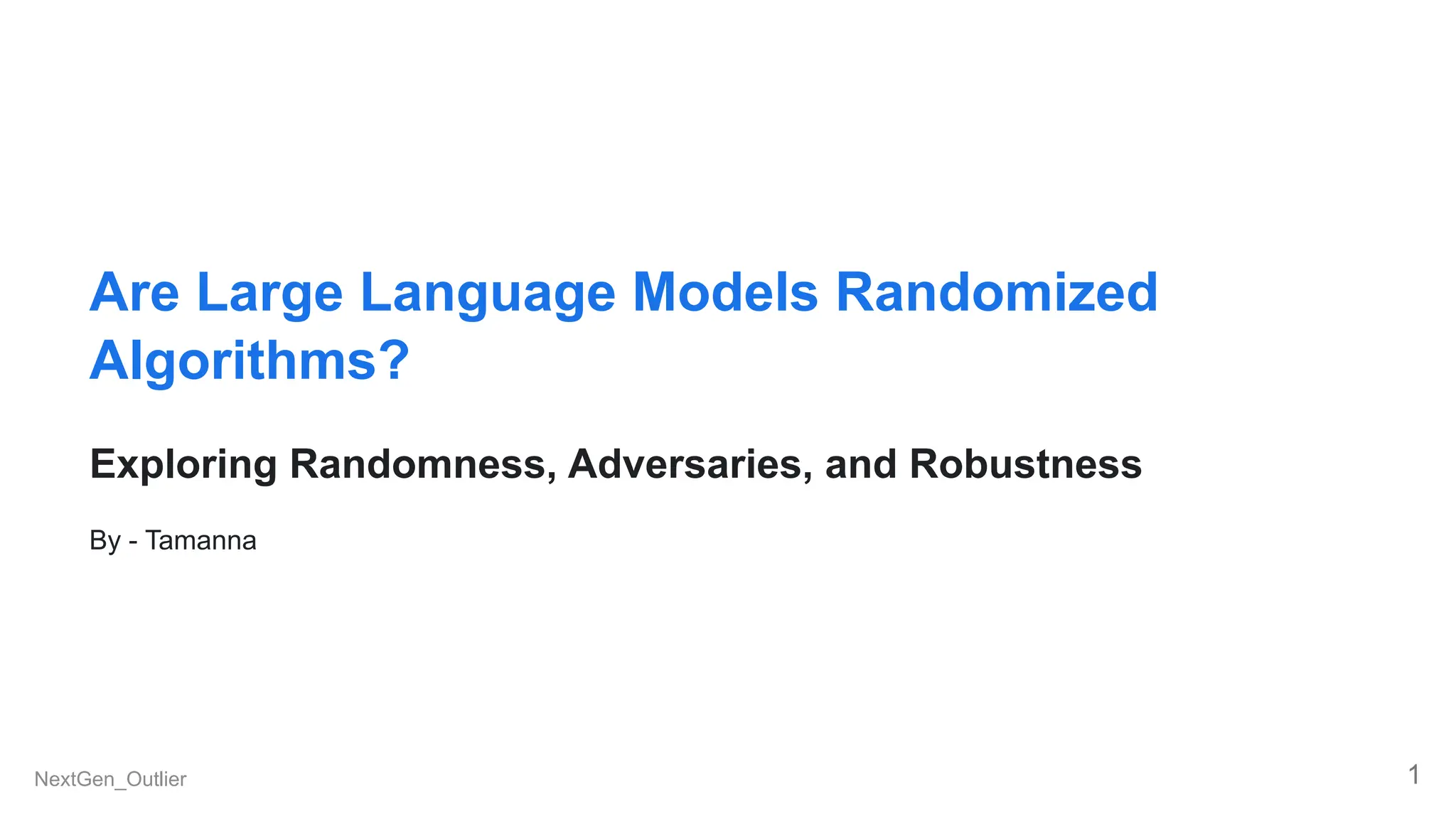

![Quicksort with Random Pivot

import random

def quicksort(arr):

if len(arr) <= 1: return arr

pivot = random.choice(arr)

left = [x for x in arr if x < pivot]

middle = [x for x in arr if x == pivot]

right = [x for x in arr if x > pivot]

return quicksort(left) + middle + quicksort(right)

print(quicksort([3,1,4,1,5,9,2,6,5,3,5]))

# → [1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 5, 5, 6, 9]

NextGen_Outlier 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/llmsrandomize-251212104826-9d40be47/75/LLMs_Randomize-Are-Large-Language-Models-Actually-Randomized-Algorithms-9-2048.jpg)