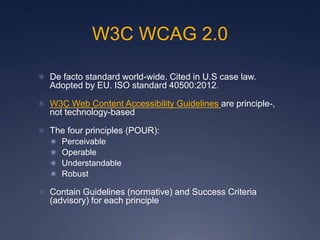

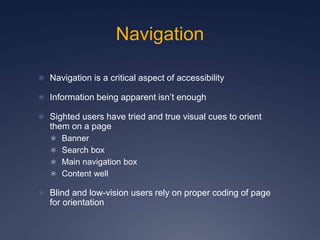

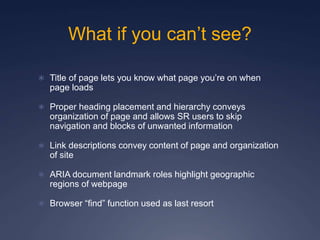

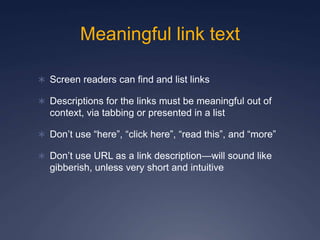

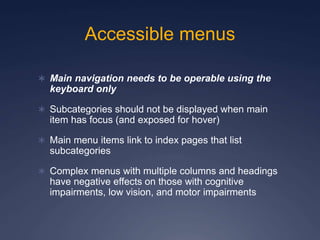

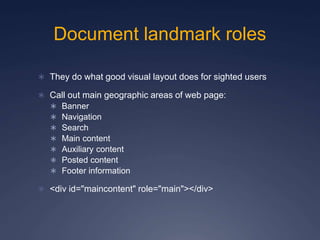

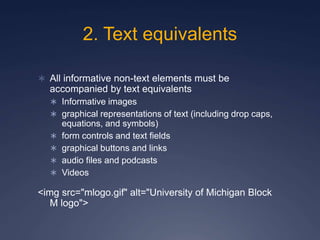

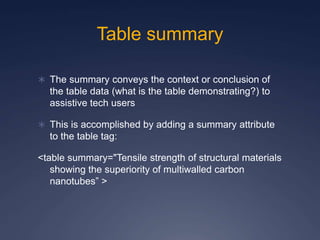

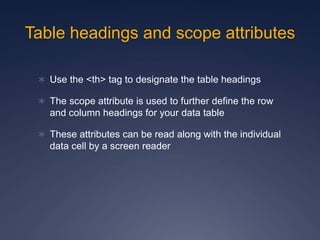

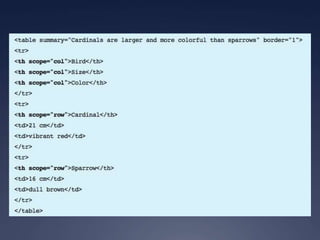

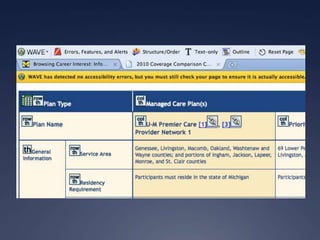

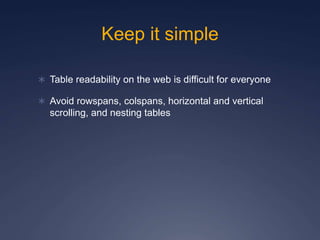

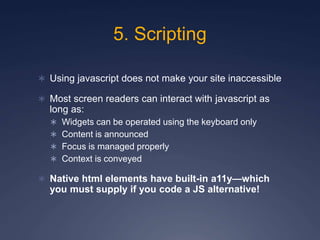

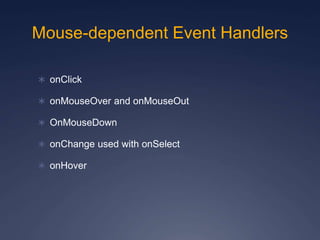

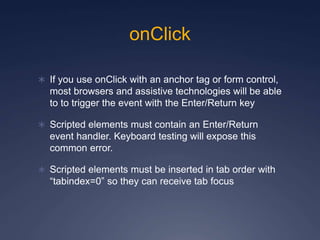

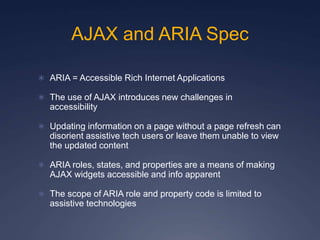

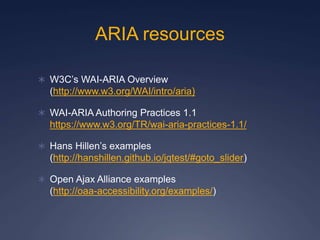

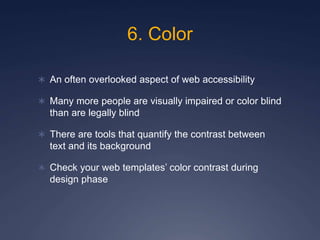

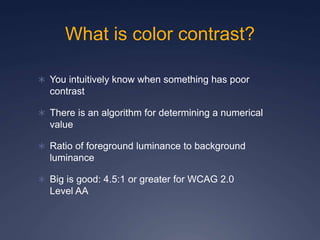

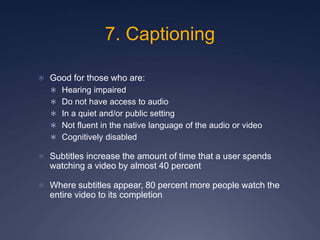

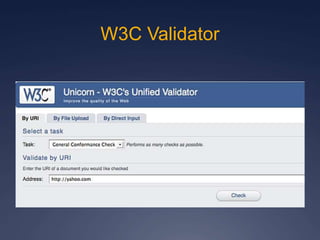

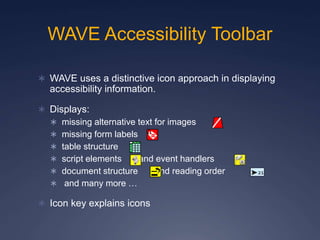

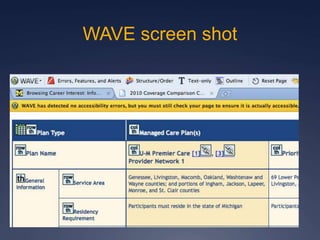

This document provides an overview of web accessibility best practices. It begins by defining web accessibility and the WCAG 2.0 guidelines. It then covers 9 key areas of accessible design: navigation, text equivalents, forms, tables, scripting, color, captioning, accessible documents, and web standards. For each area, it provides guidelines and examples. It concludes with a discussion of tools and techniques for evaluating websites for accessibility, including keyboard testing, the WAVE toolbar, and U-M resources. The overall goal is to teach designers how to make their web content perceivable, operable, understandable and robust for all users.