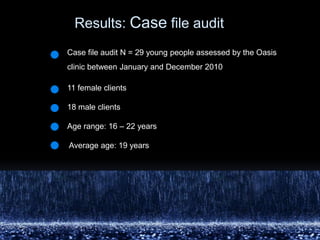

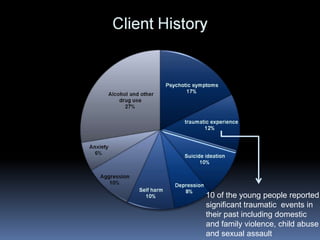

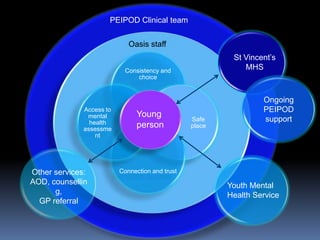

The document summarizes findings from an evaluation of an early intervention outreach mental health clinic for young people experiencing homelessness in Sydney, Australia. Key findings include:

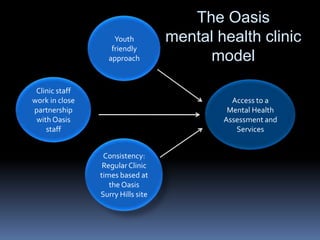

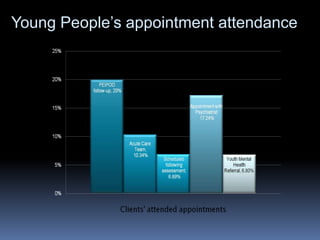

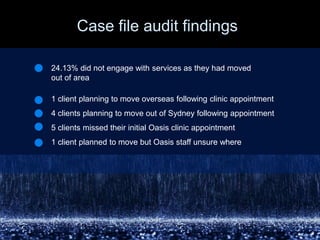

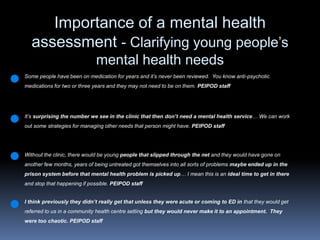

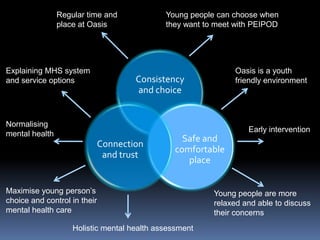

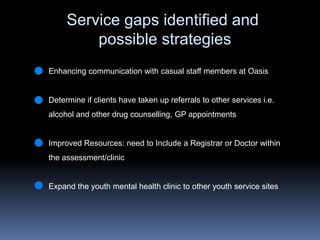

1) The clinic facilitated improved access to mental health services for young people by providing assessments and brief interventions directly at a youth shelter.

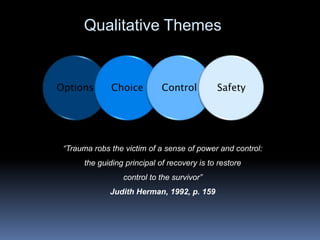

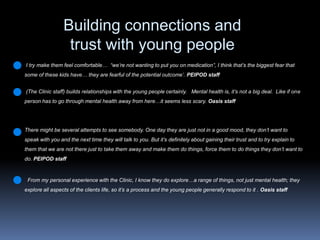

2) Both clients and shelter staff reported that the clinic helped normalize mental health and increased comfort with mental health services.

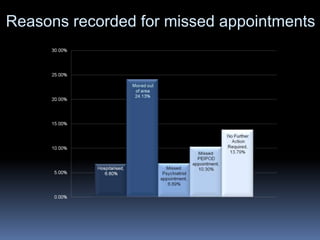

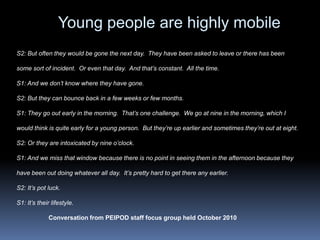

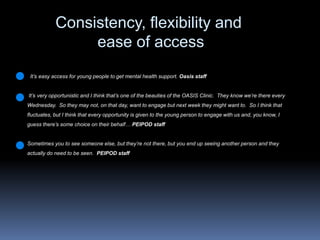

3) Maintaining a consistent weekly presence at the shelter was important for building trust and addressing the mobility of the youth experiencing homelessness.