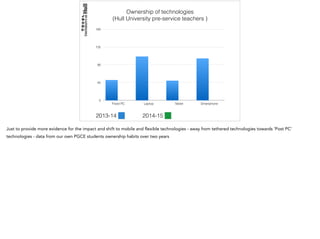

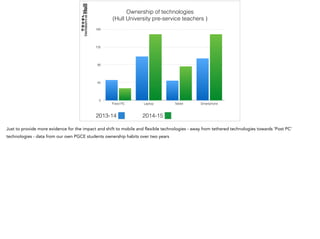

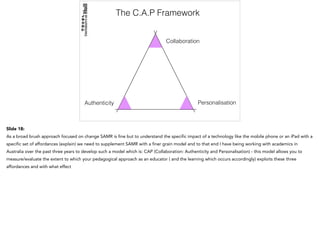

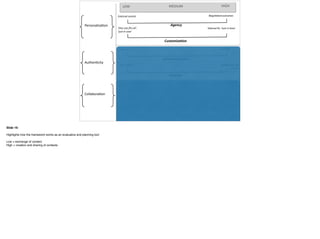

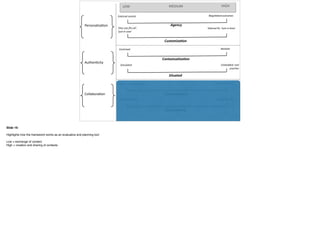

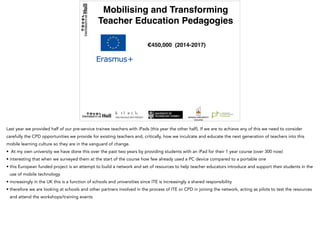

The document discusses the impact of mobile technologies on education, highlighting the ongoing information revolution that is reshaping knowledge dissemination. It outlines previous research regarding mobile devices in educational settings and emphasizes the significant learning that occurs both intentionally and informally through these devices. The presentation also addresses frameworks for understanding mobile technology's role in pedagogical transformation.