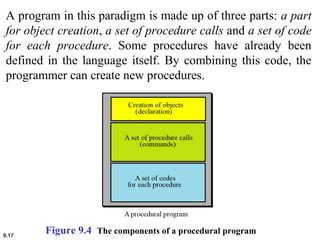

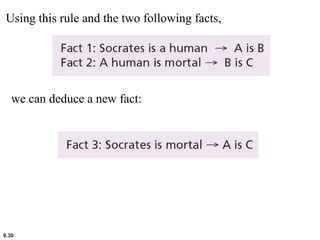

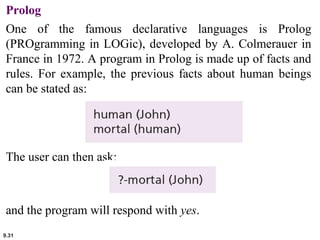

The document discusses the evolution of programming languages from machine language to high-level languages. It describes four common programming paradigms - procedural, object-oriented, functional, and declarative. It also discusses common concepts found in most procedural and object-oriented languages such as identifiers, data types, variables, and literals.