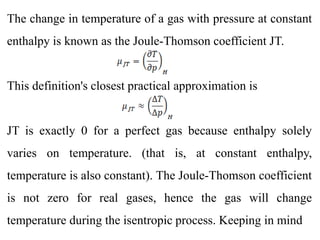

The document discusses the Joule-Thomson experiment and coefficients. In the experiment, a gas passes through a porous barrier from an area of high pressure (p1) to low pressure (p2) while maintaining adiabatic and isentropic conditions. This results in a temperature change (T2) despite no change in enthalpy (H). The temperature change per pressure change at constant enthalpy is known as the Joule-Thomson coefficient (JT). For ideal gases, JT is zero as enthalpy only depends on temperature. However, for real gases JT is non-zero, allowing measurement of other thermodynamic properties that are difficult to directly measure.