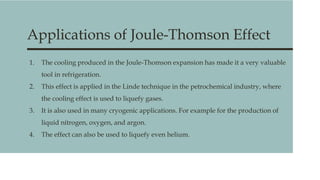

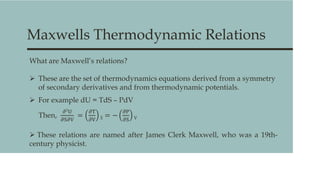

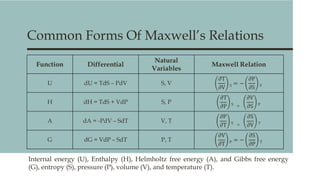

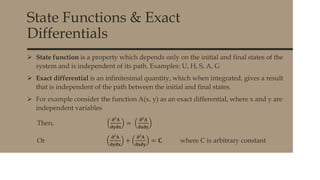

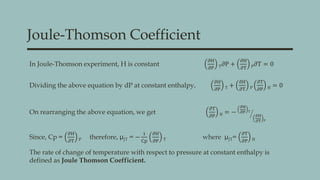

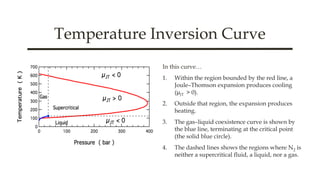

The document discusses key concepts in thermodynamics including Maxwell's relations, state functions, and the Joule-Thomson effect. It explains the significance of the Joule-Thomson coefficient, its implications for gas behavior during expansions, and its applications in refrigeration and cryogenics. Key equations and principles are outlined to demonstrate the relationships between temperature, pressure, and enthalpy in these processes.

![Joule-Thomson Coefficient For An Ideal

Gas

We know that, μJT = −

1

Cp

𝜕H

𝜕P T =

𝜕T

𝜕P H

Therefore, , μJT = −

1

Cp

𝜕(U+PV)

𝜕P T …(Since, H = U +

PV)

= −

1

Cp

[

𝜕U

𝜕P T +

𝜕(PV)

𝜕P T ]

= −

1

Cp

[

𝜕U

𝜕V T

𝜕V

𝜕P T +

𝜕(PV)

𝜕P T ]

For an ideal gas,

𝜕U

𝜕V T = 0

Also, PV = constant so,

𝜕(PV)

𝜕P T = 0

Therefore, μJT = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thermodynamics-210712091847/85/Thermodynamics-10-320.jpg)