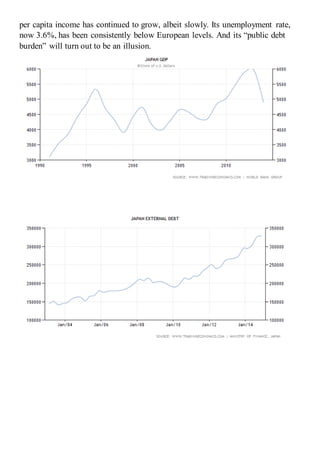

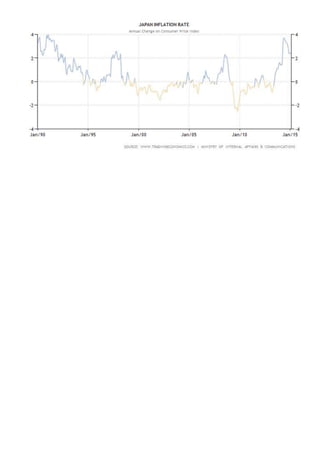

Japan's national debt has grown to 230% of GDP as it has run large fiscal deficits since 1990. The Bank of Japan now buys more government bonds each year than are issued to fund the deficit, effectively monetizing the debt. This keeps interest payments low and reduces the residual debt held by others over time. While some fear this could lead to high inflation, others argue Japan's experience shows permanent monetization may be necessary to manage an otherwise unsustainable debt burden, and it has not negatively impacted the economy.