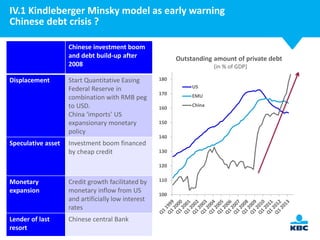

110

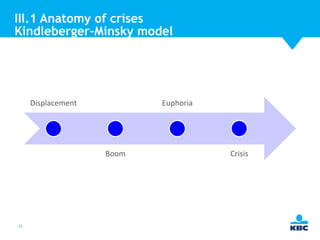

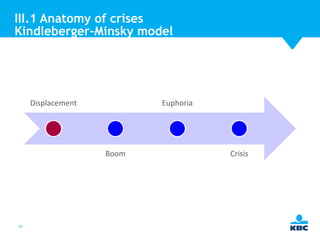

Bank credit expansion

100

Lender of last

resort

China

90

80

Chinese government

70

60

45

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Source: BIS

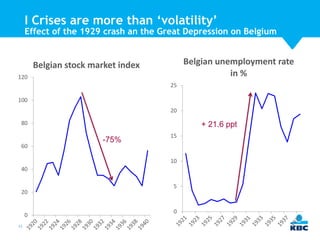

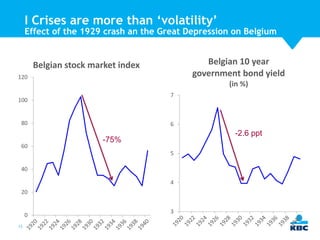

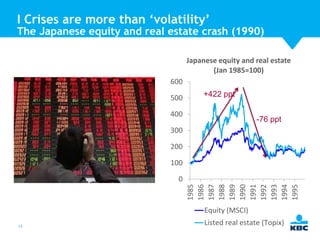

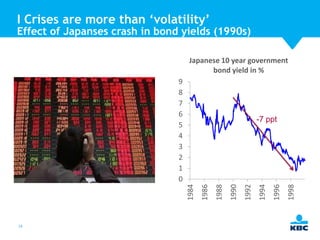

�IV.2 Lessons from history

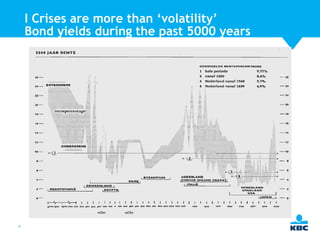

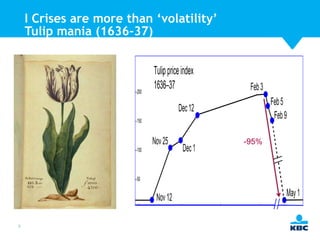

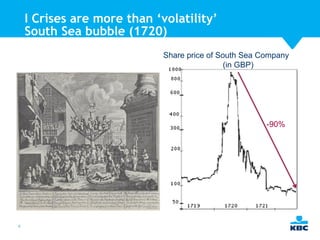

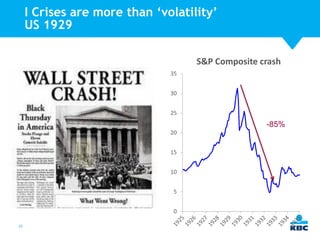

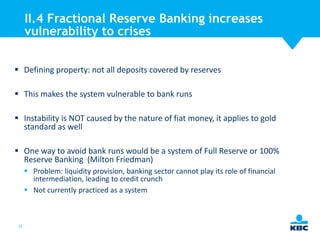

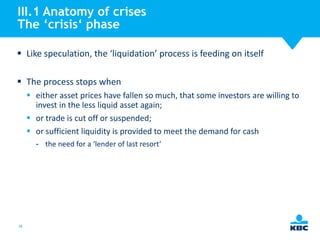

1. Crises are inevitable in a debt-based monetary system with fractional reserve banking

2. Excessive credit growth and asset bubbles will eventually burst

3. A lender of last resort is needed to prevent liquidity crises from turning into solvency crises

4. Regulation is needed to limit the build-up of excessive risks in the financial

![IV.3 Lesson for quantitative risk modelling

Time dependency of correlation data creates an illusion of safety

“In complex systems, such as financial systems, correlations are not

constant but vary in time. [...] The average correlation among stocks

scales linearly with market stress. [...] Consequently, the diversification

effect which should protect a portfolio melts away in times of market loss,

just when it would most urgently be needed.” (Preis et al. (2012))

One way to address time-dependency of risk models could be using statedependent correlation data, i.e. conditional (state dependent) instead of

unconditional correlations

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/internelezingknowyourcrisis-140206032852-phpapp01/85/Anatomy-of-financial-crises-56-320.jpg)