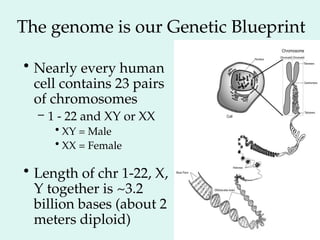

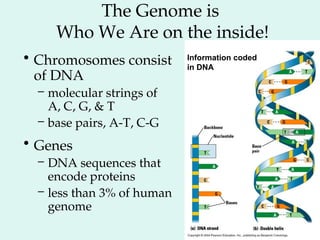

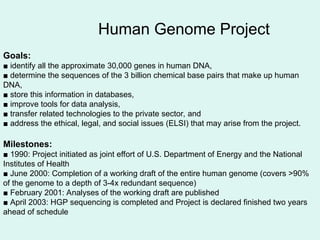

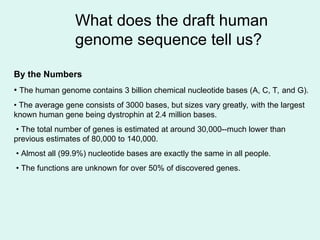

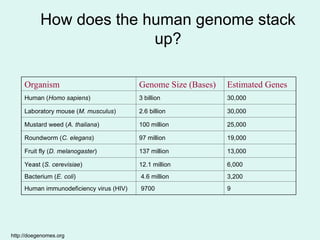

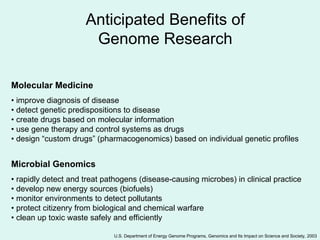

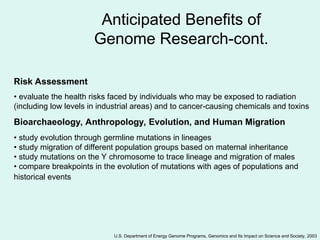

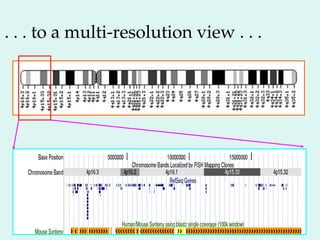

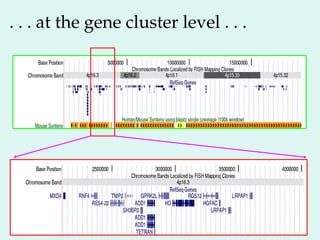

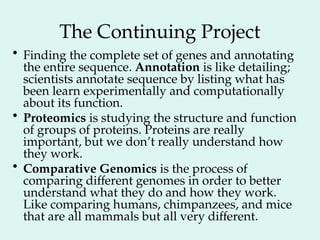

The Human Genome Project, initiated in 1990, aimed to understand the human genome's role in health and disease, ultimately leading to better diagnostics and treatments. By 2003, it successfully identified and mapped approximately 30,000 genes within the human DNA, revealing significant insights into genetic similarities and variations among individuals. The project's advancements in sequencing technology have transformed biological research and opened pathways for molecular medicine, microbial genomics, and forensic applications.