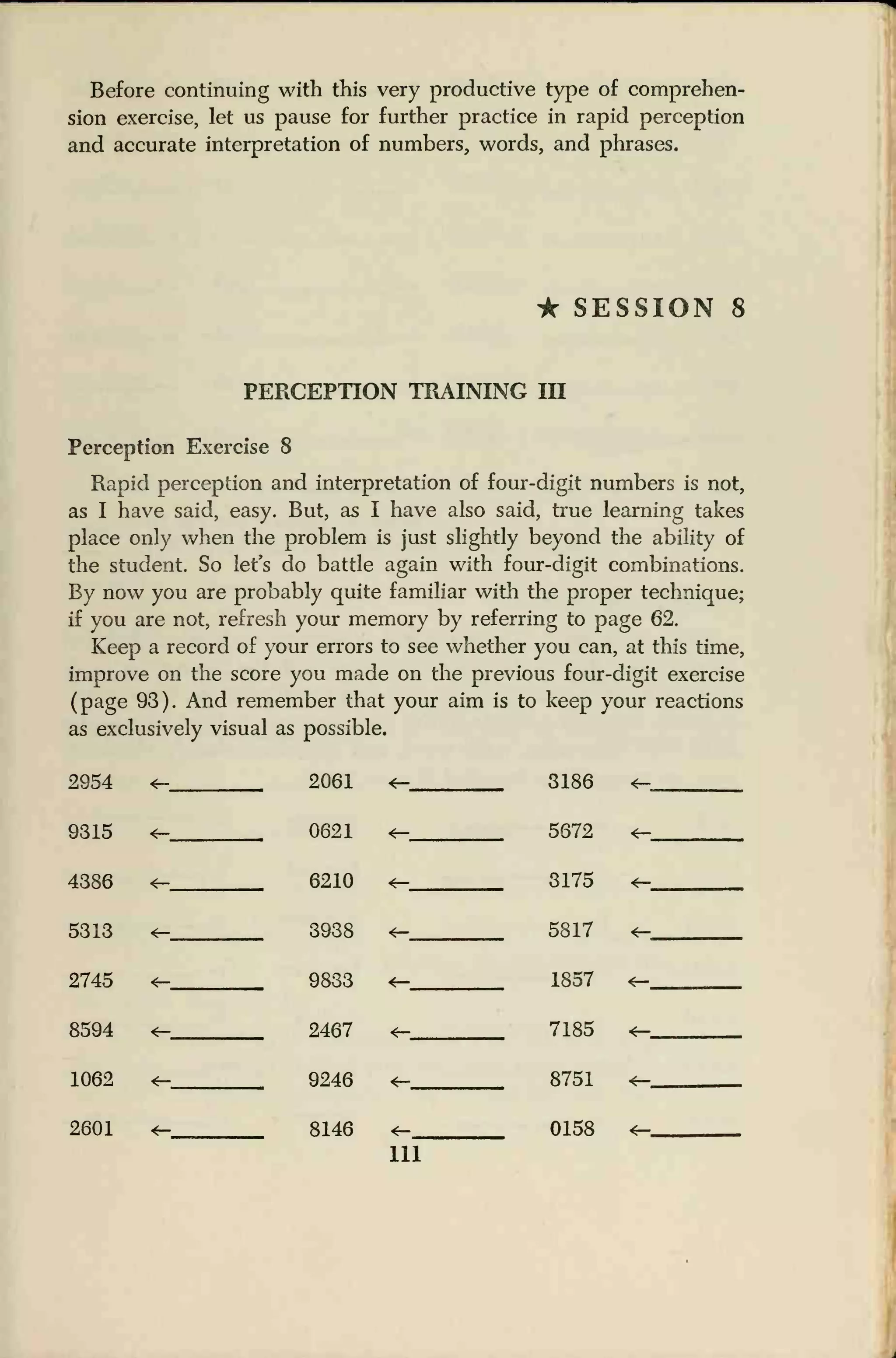

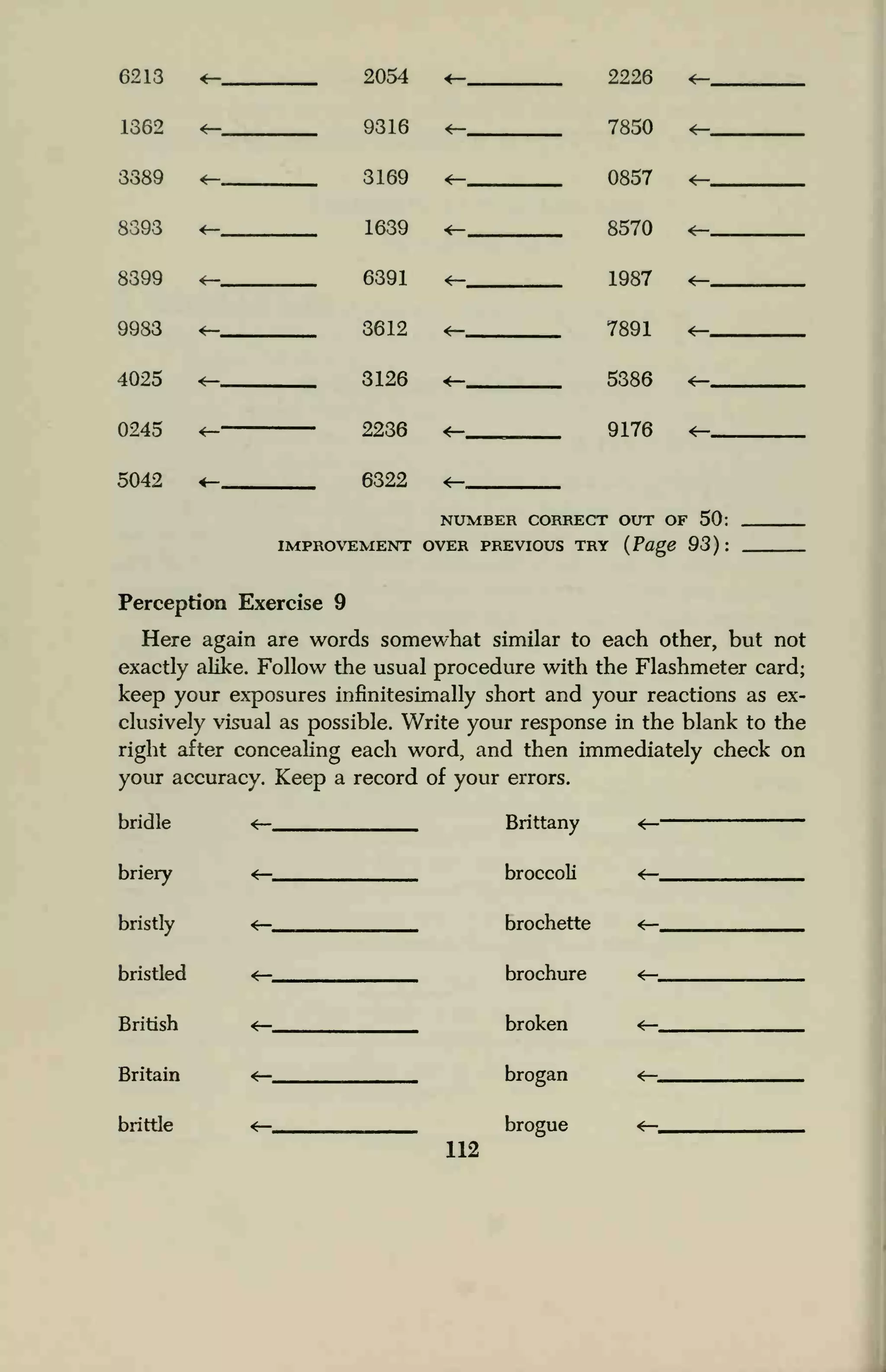

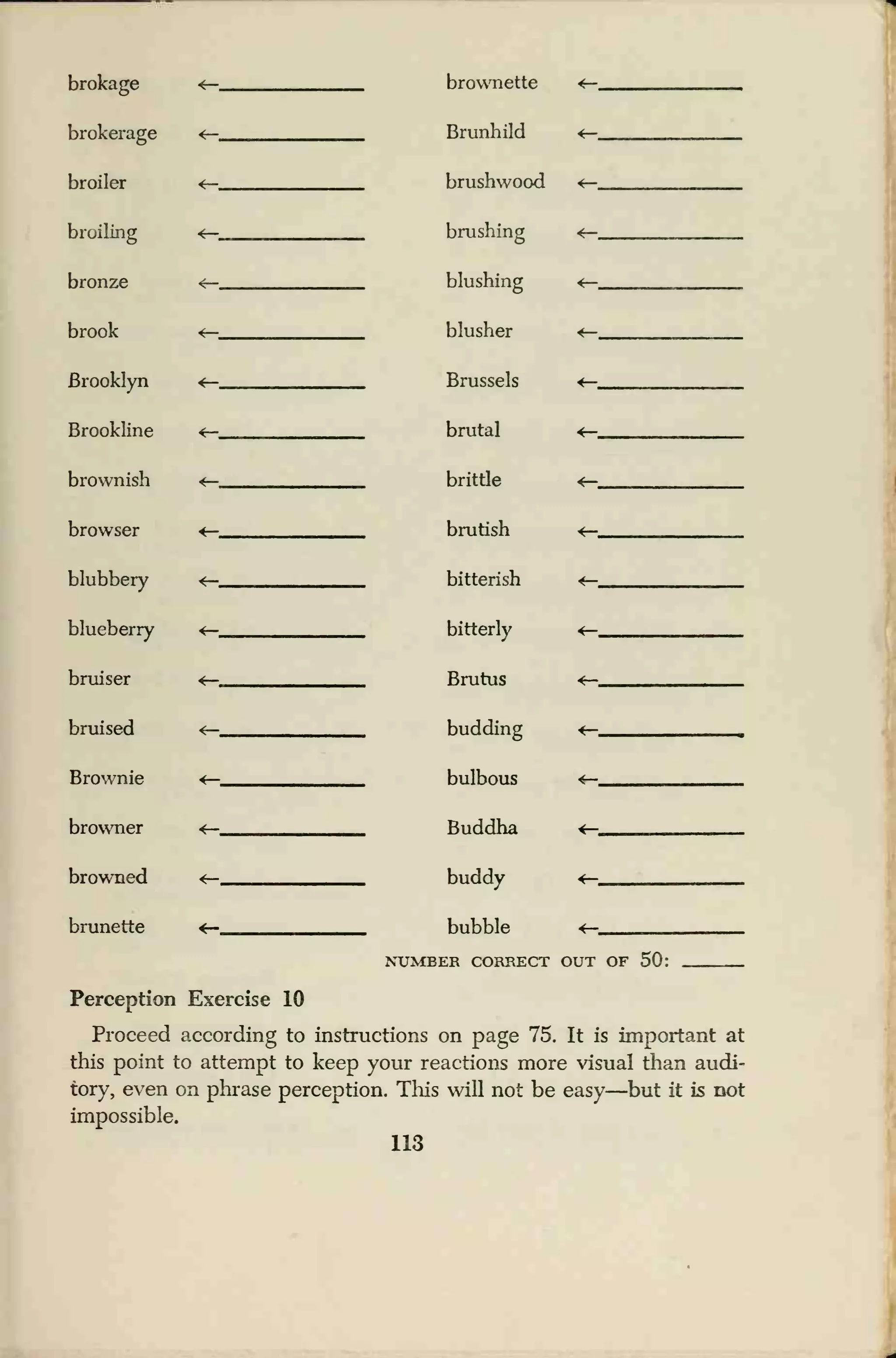

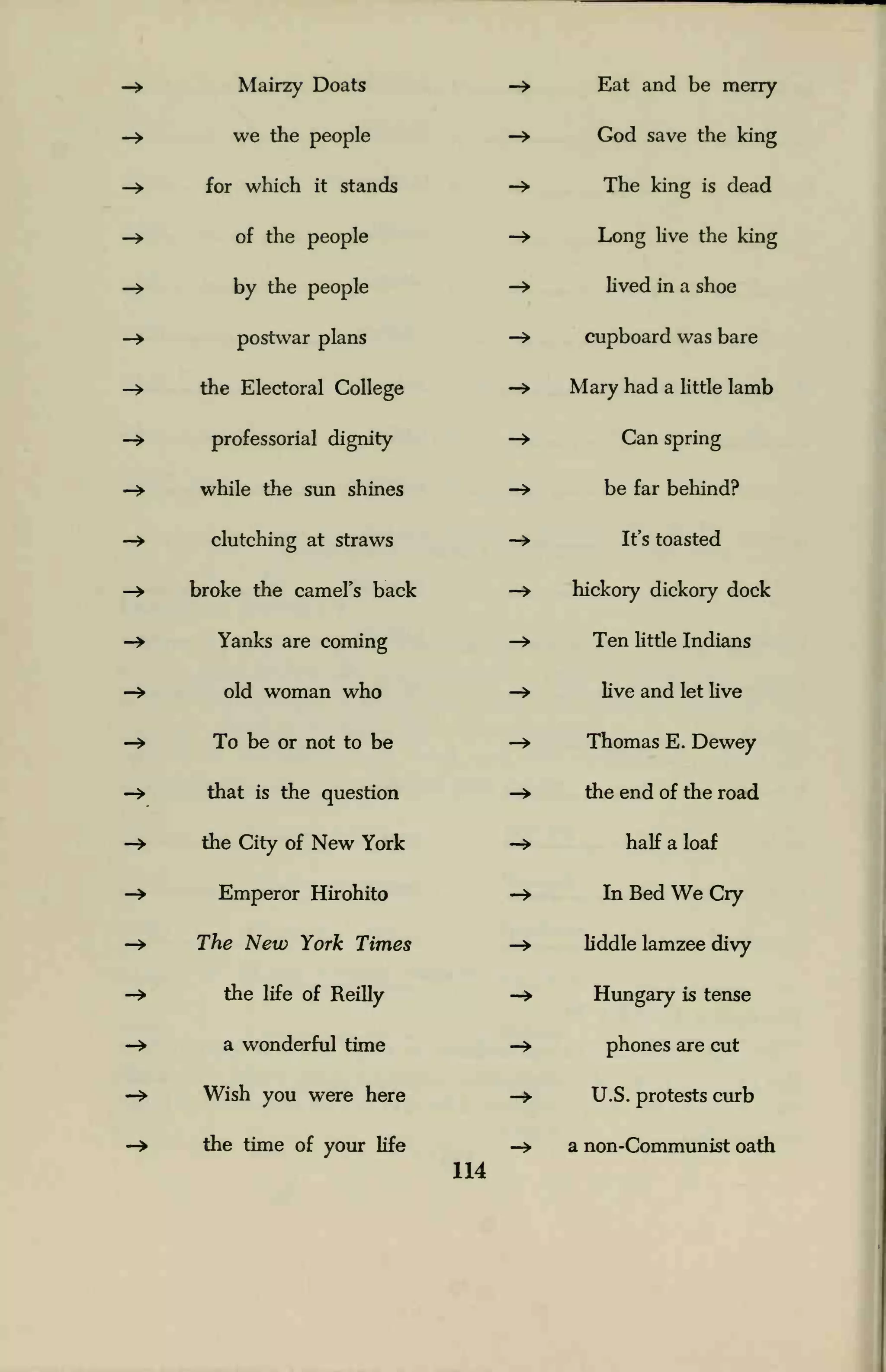

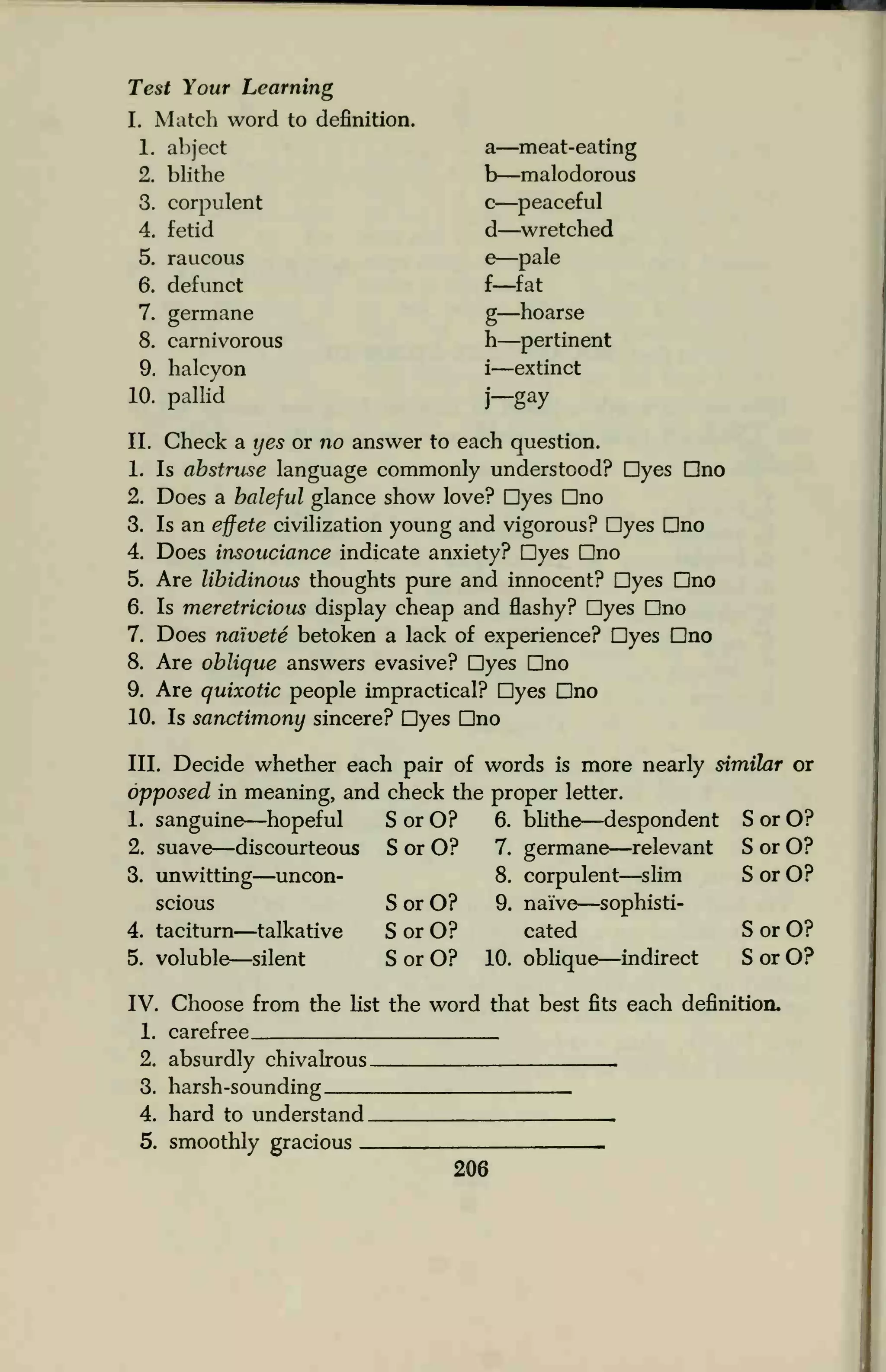

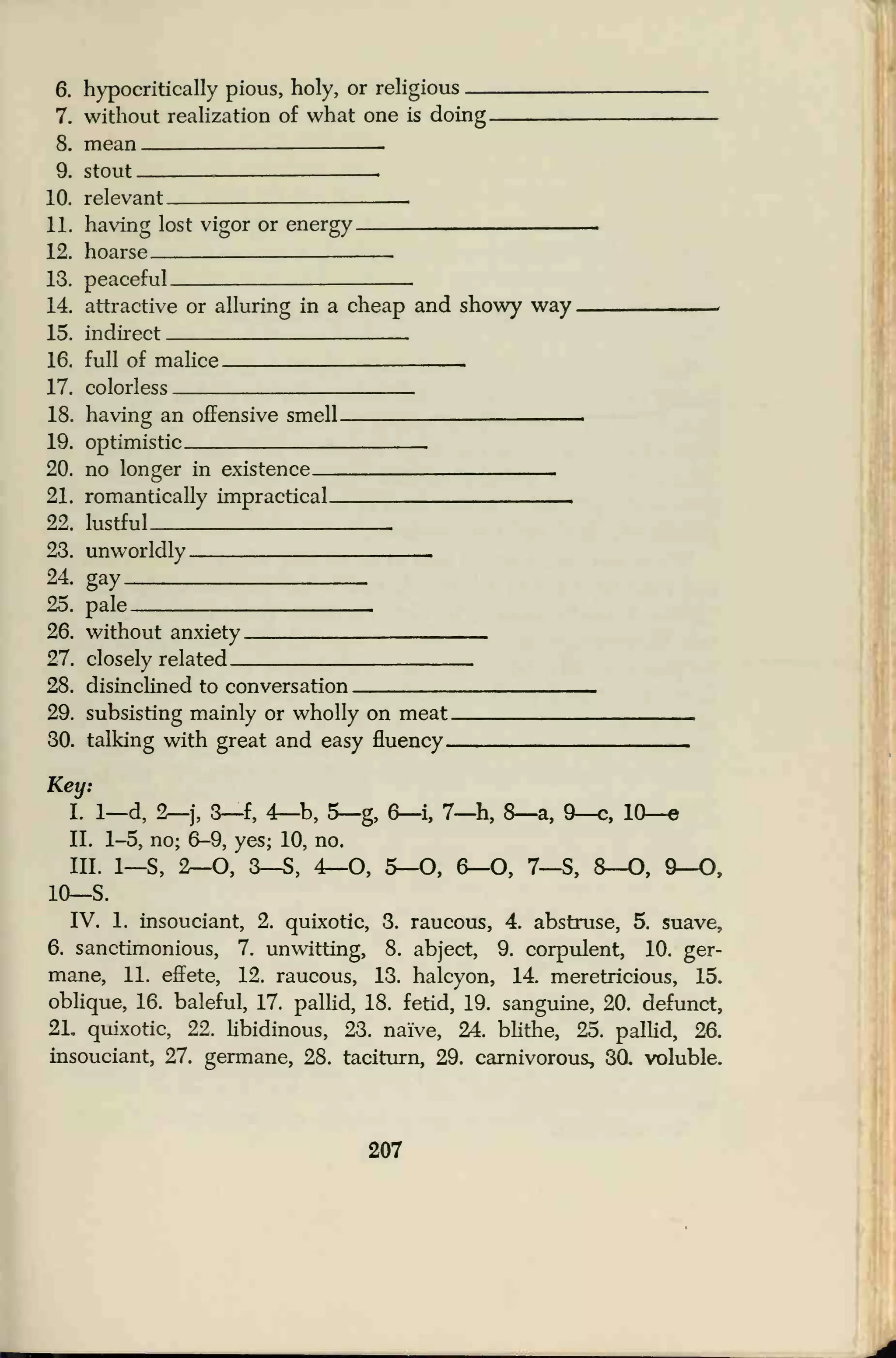

This document provides instructions for a 30-day training program to improve reading speed and comprehension. It begins with an introduction that explains the benefits of the program and recommends dedicating 1 hour per day to complete the 30 sessions over 1-4 months. The subsequent chapters cover techniques for identifying main ideas, improving perception skills, reducing vocalization, increasing vocabulary, learning to skim, and practicing comprehension exercises. Tables are included with sample passages and exercises for each session. The goal is to increase reading rates by 25-100% while also enhancing understanding.

![paragraph 7 ("Had you taken a lighter attitude . . .") and the

key phrase in this sentence is "accepted me as one of the class. . .

."

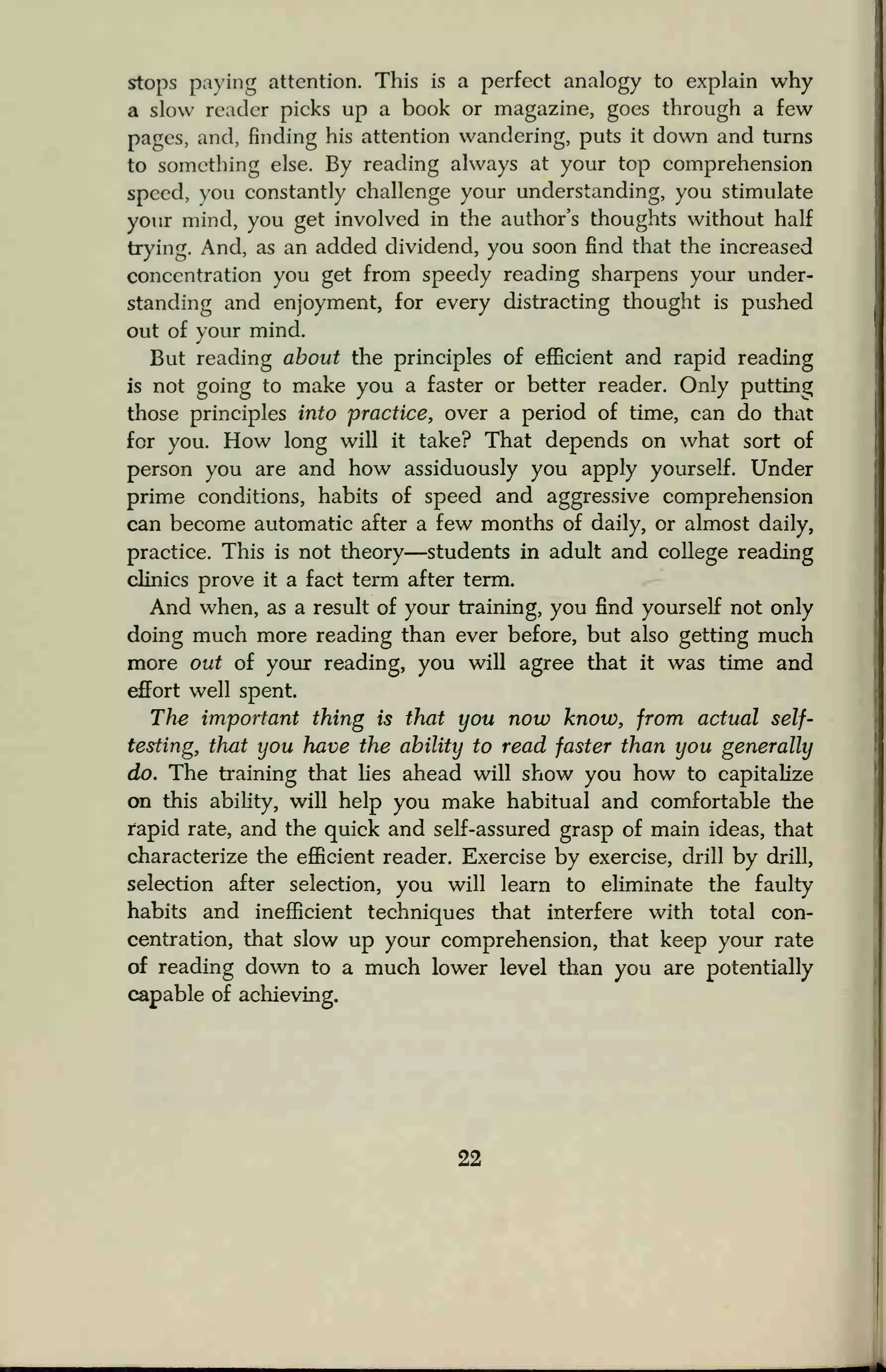

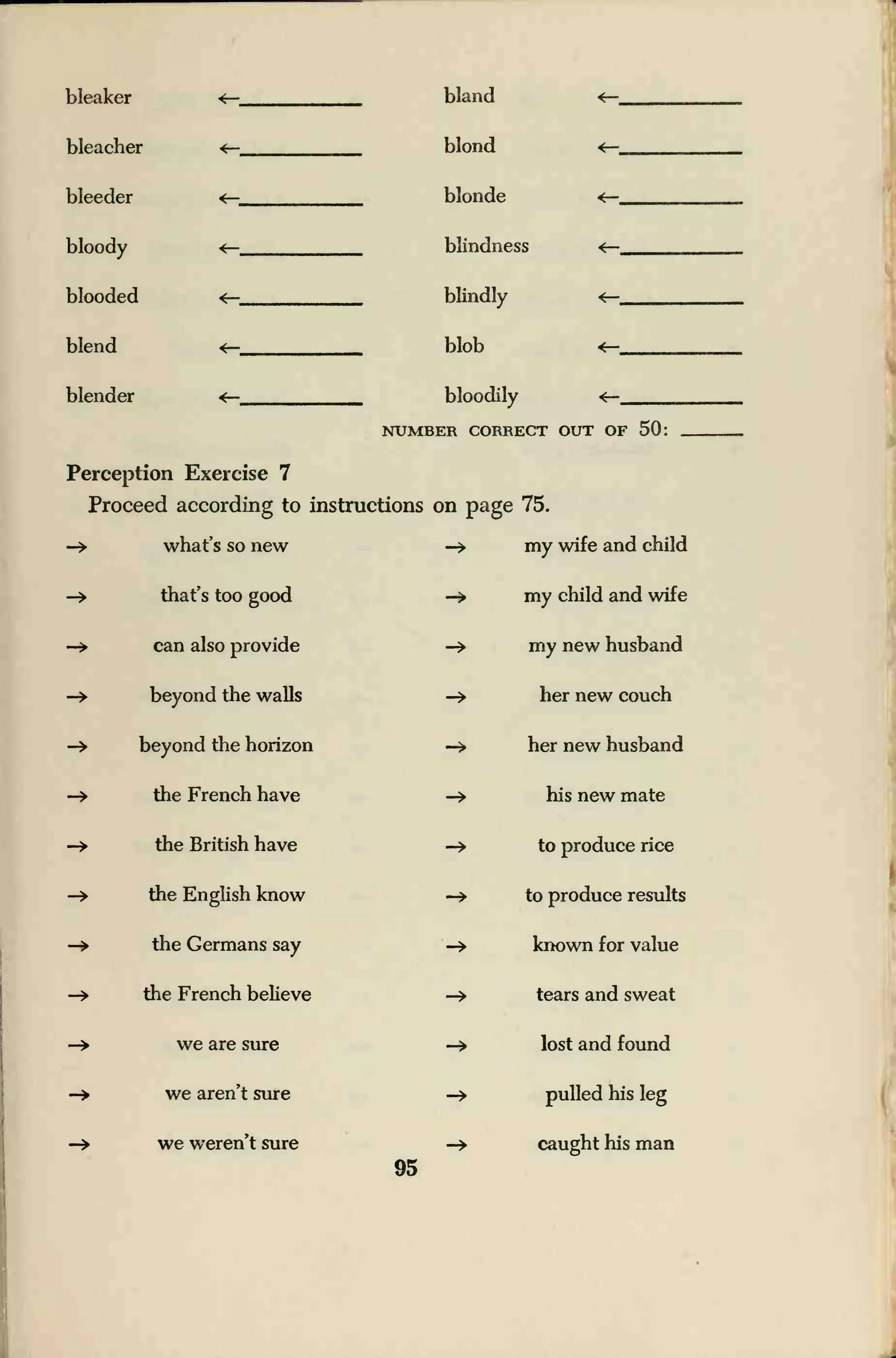

The author has used over 25 per cent of his material to prepare

you for his main idea, that a stutterer craves and needs acceptance

—and then continues with an even larger block of material, right

through paragraph 13, elaborating on and pounding home this

same central point. In paragraph 14, the writer restates the theme

(" . . that the aim in guiding the personality development of the

stutterer should be the same [i.e., acceptance] as the aim for any

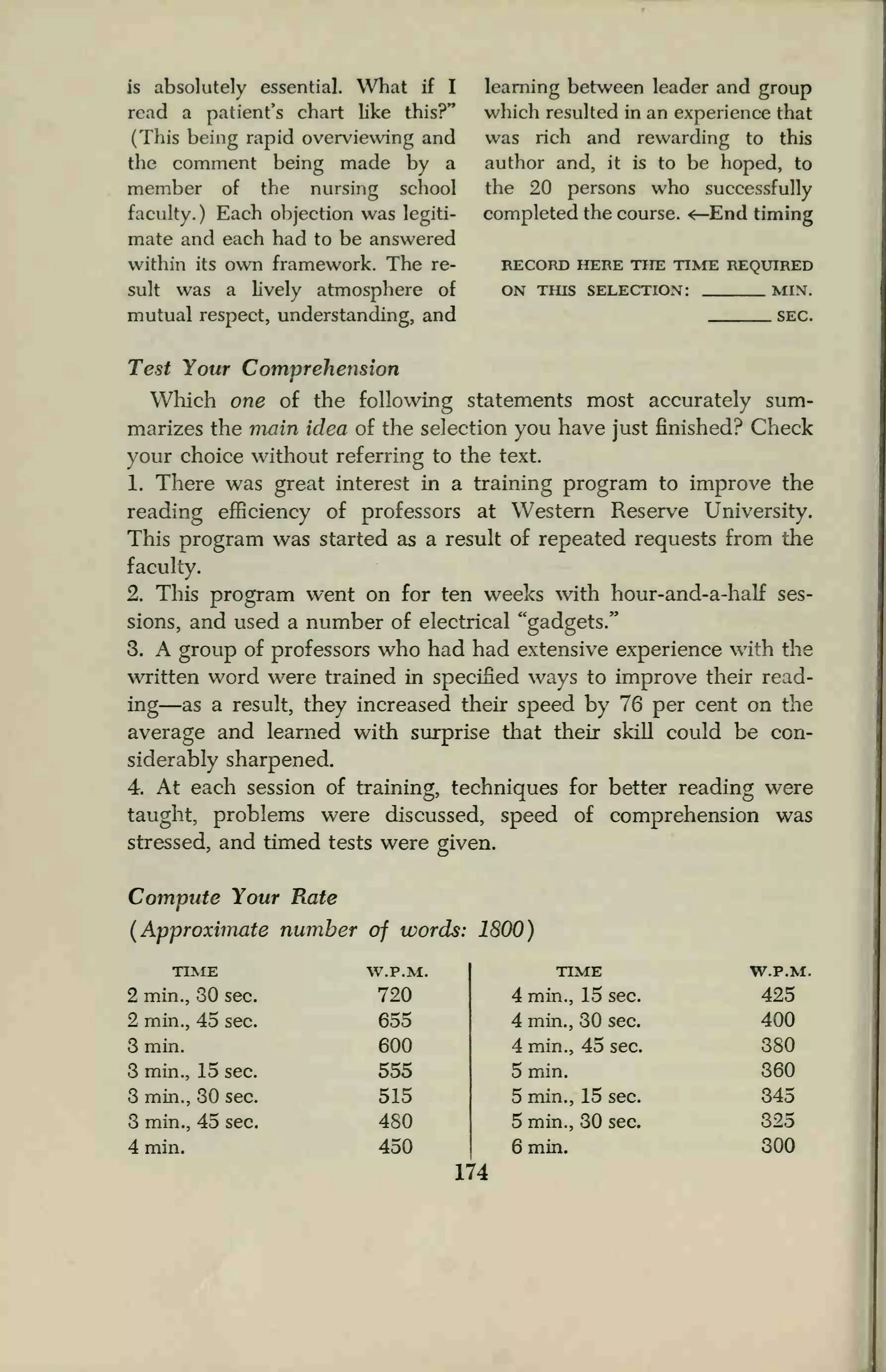

other child . . ."); and then, in another key sentence of the piece,

he broadens his theme to include the idea that acceptance results

in "a feeling of personal security. . .

"

Paragraphs 15 through 17 add more details to support the theme,

with paragraph 20 ("My confidence increased . . . and better

speech resulted") restating, in different words, the idea of personal

security.

Correct choice on the comprehension test is statement 1.

No one, of course, goes through this conscious and elaborate type

of analysis as he reads. But accurate comprehension of the final

meaning of any piece of writing is based on a recognition, perhaps

largely subverbal, of how the author has organized his material,

how he has knit together the various strands of his fabric, how he

combines the parts to produce a total effect. And the efficient

reader, intent on extracting the essence of a page as quickly as

possible, has always some feeling, whether or not he verbalizes it,

of how the broad sections of material are related and of how the

important concepts are supported, explained, clarified, or illustrated

by subordinate details.

My purpose in asking you to go back over each selection as you

study the analysis is to sharpen your sense of the structure of

material, to develop your skill in differentiating subordinate ele-

ments from main ideas. The more practiced you become in recog-

nizing how details are used to introduce, bolster, pound home,

clarify, or illustrate main ideas, the more rapidly and successfully

will you be able to pull these ideas out of your reading, and the

clearer will be your grasp of the final meaning of what an author

is saying to you.

So let us continue this valuable practice on the next selection.

Push through the details rapidly, keep on the alert for the main

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-59-2048.jpg)

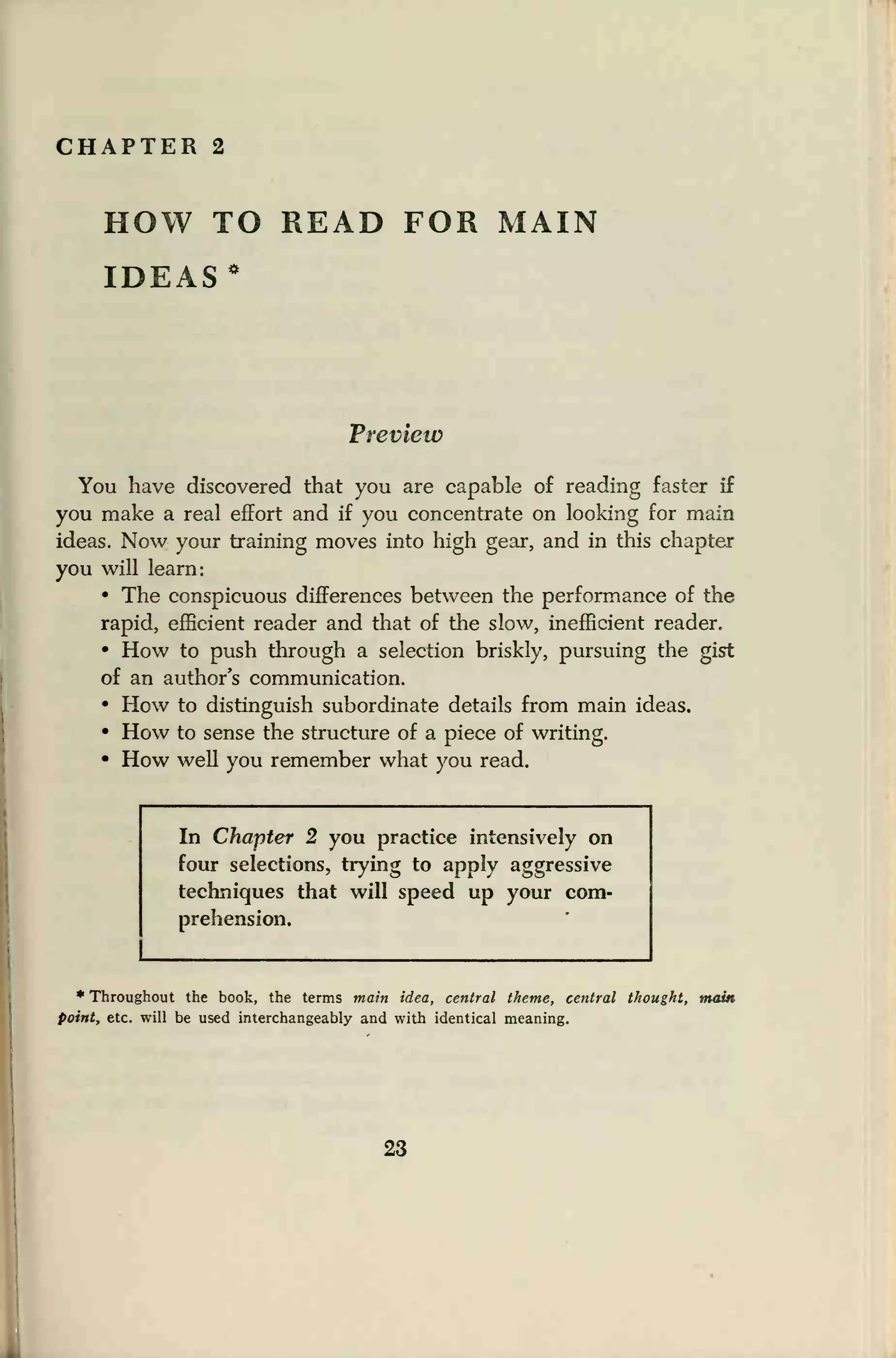

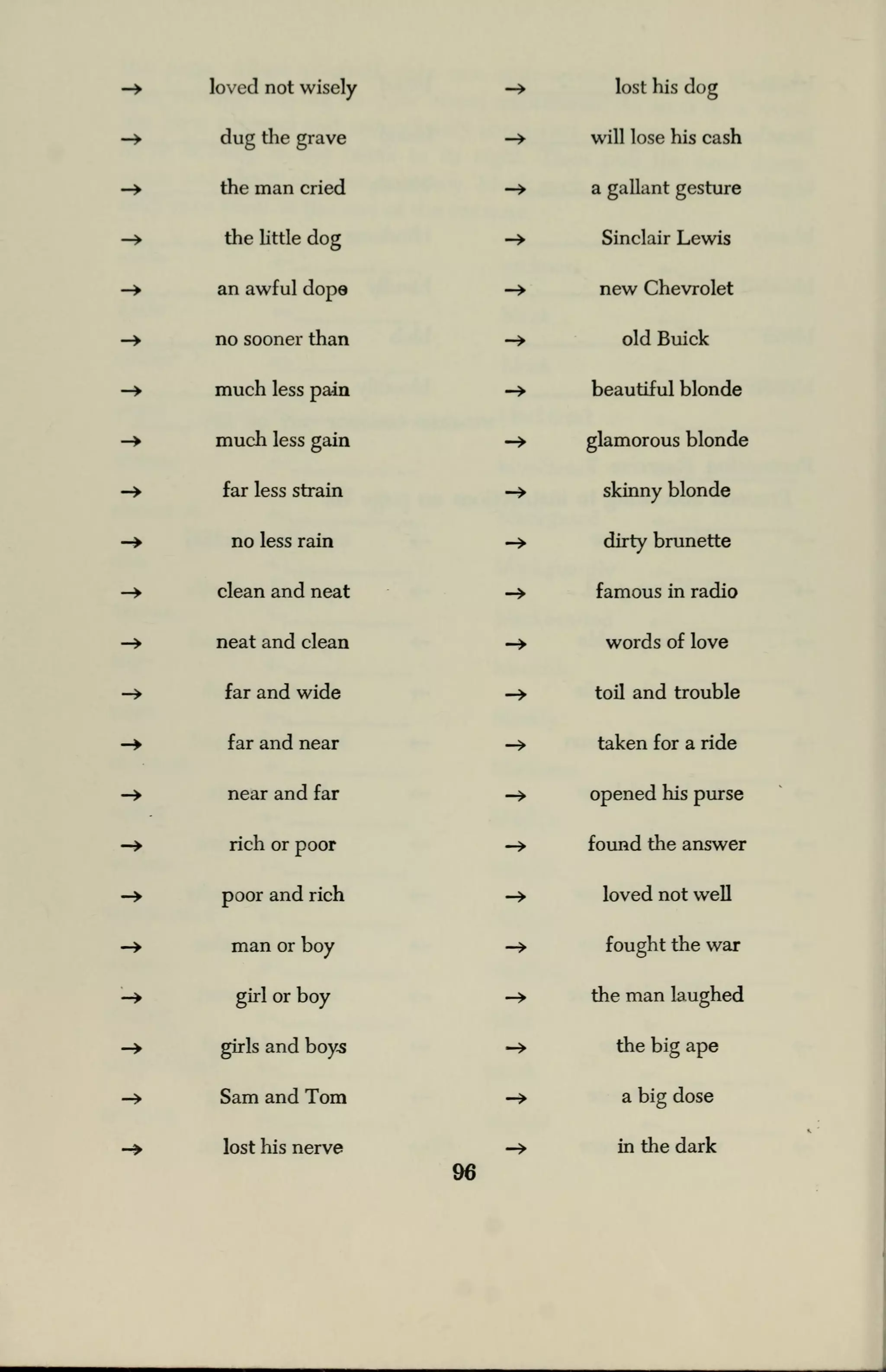

![School and Guidance Center, San Antonio, Texas, explain the prin-

ciple behind such training as follows:

Since we use but a fraction of our capacities, according to re-

search psychologists, and since approximately 80 per cent of our

knowledge comes to us through our eyes, increasing usable vision

and broadening spans of perception and recognition . . . [has as

its purpose to] increase speed, comprehension, accuracy, and self-

confidence in reading. . . .

By gradually increasing the speed of the flash and the amount of

material to be perceived, unnecessary eye movements are eliminated

and the spans of perception and recognition broadened. This tech-

nique drives vision impulses to lower reflex levels, where, as learning

proceeds, the interval necessary between reception and interpretation

is reduced.

A similar explanation is offered by The Air University Reading

Improvement Program, from which the following excerpts are

quoted with permission:

The use of the tachistoscope in rapid recognition was developed

by Dr. Samuel Renshaw at The Ohio State University. When the

armed services realized the need for speed-up training in aircraft

recognition, Army and Navy pilots used the tachistoscope with out-

standingly successful results. Dr. Renshaw is one of our most promi-

nent leaders in experimentation with visual problems and has tested

the tachistoscope widely for reading benefits. . . .

The tachistoscope helps the reader approach his limit of precision

of vision and peripheral span. The untrained eye has a limited field

of vision but with training on quick recognition this field of functional

recognition expands.

The tachistoscope has other values. It provides training in several

visual processes simultaneously. Not only does it increase the eye

span, it also decreases the length of eye fixation. The shutter of the

Flashmeter can be controlled so that an interval as short as %oo °^ a

second can be obtained. For purposes of training in the Reading

Laboratory %oo second gives enough speed to provide practice

in quickening the eye fixation, since the shortest recorded fixation

during reading is several times as long as %00 second.

Another value of the tachistoscope is that it forces the reader to

grasp material as a form-field, seen as a whole. With such a quick

flash he cannot vocalize or get side-tracked on elements of the visual

pattern; he must take it in at once or it is gone as soon as the after-

image fades. . . .

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-83-2048.jpg)

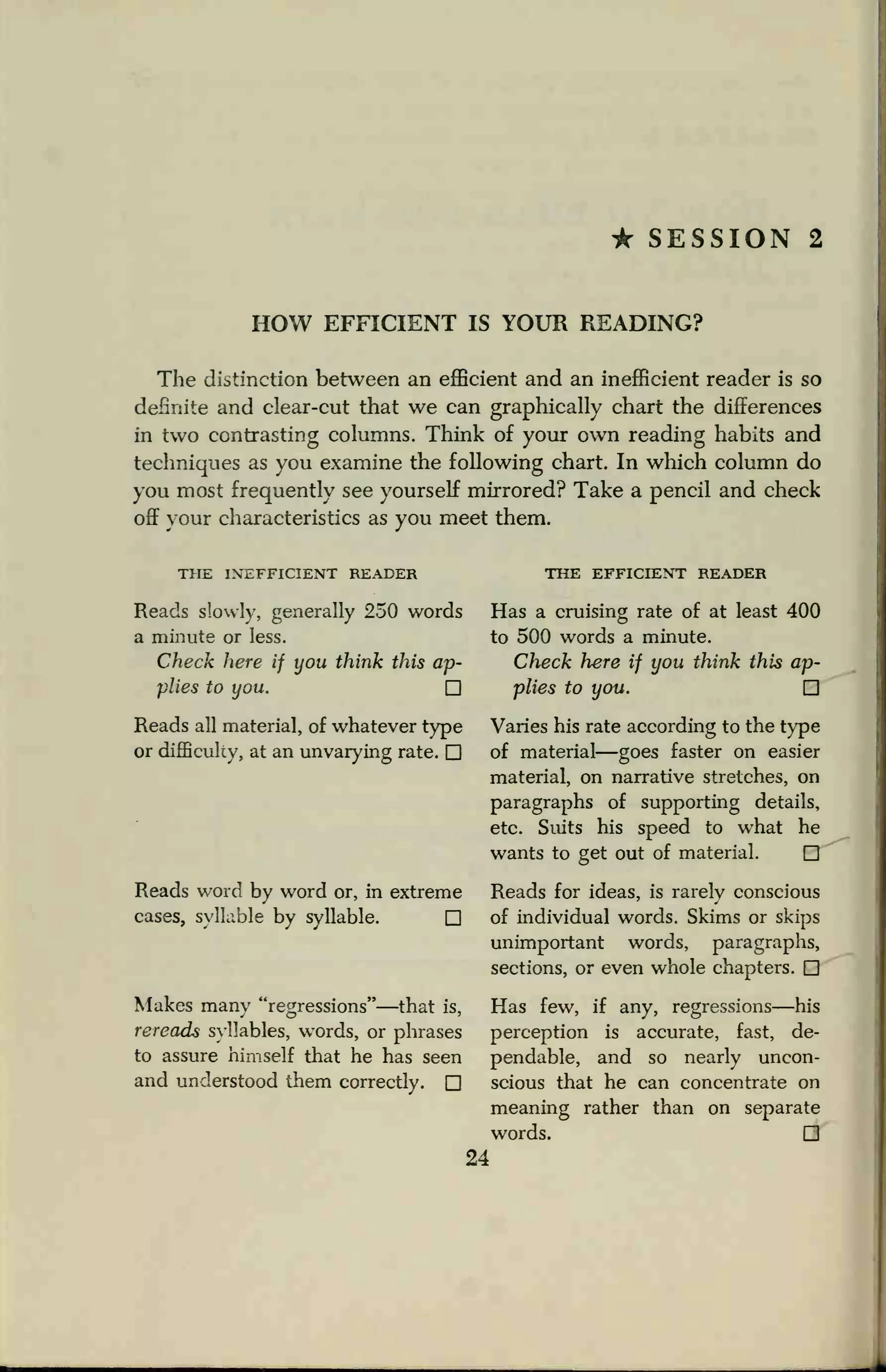

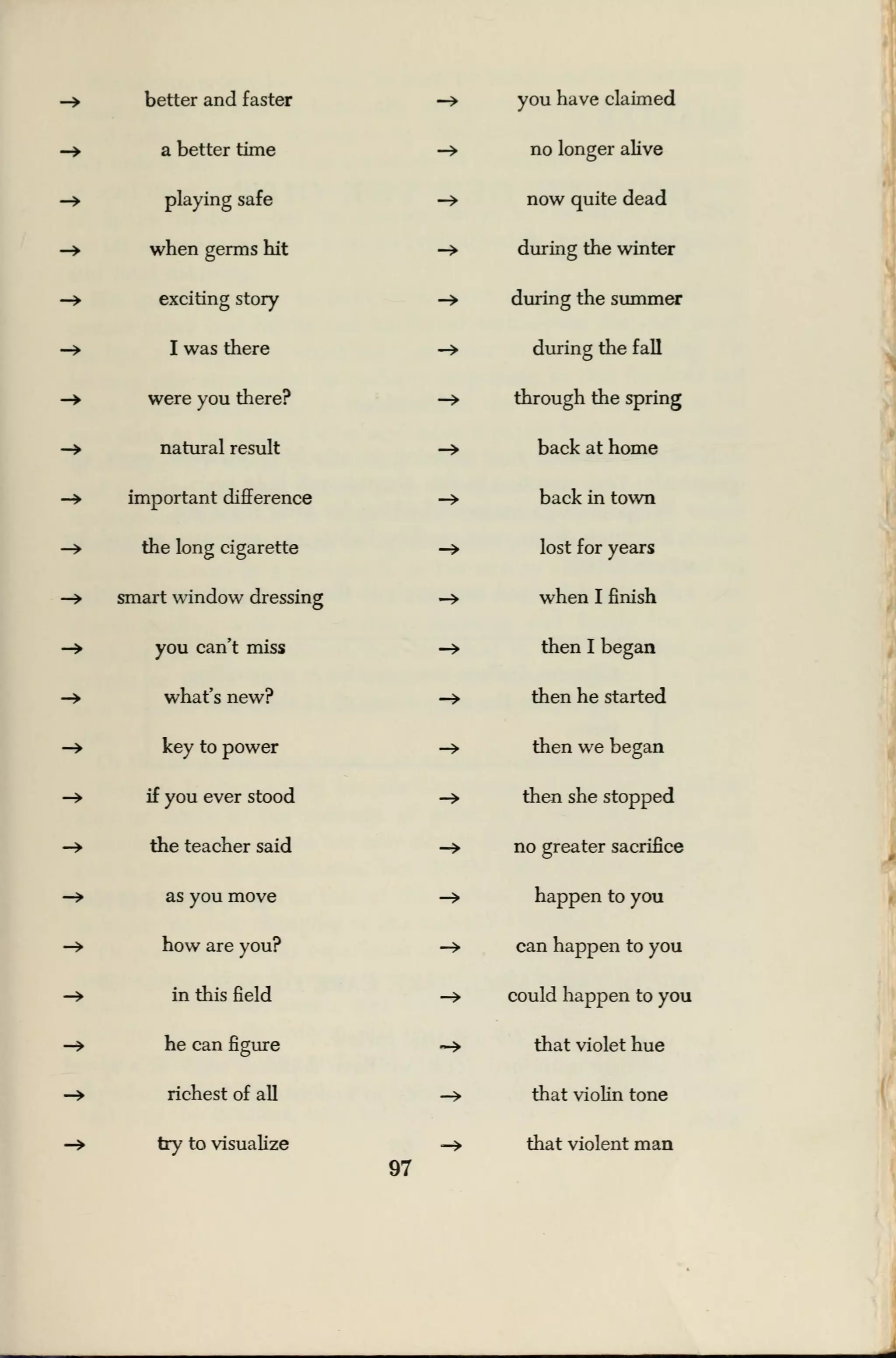

![The skillful reader may make occasional and voluntary regres-

sions, but solely out of actual and realistic need, never from habit

or compulsion or because he doesn't entirely trust his ability to

comprehend. He goes back to reread a word or phrase only if he is

certain that it is utterly useless to go on without doing so; otherwise

he keeps pushing rapidly ahead, for he is far more interested in total

meaning and in ideas than he is in individual words or phrases or

details.

Of course, if ideas are expressed ambiguously or confusingly, or

in extremely complicated or involved language, meaning will be

elusive, and rereading and still further rereading may be necessary

—but then the fault lies witii the writer, not with the reader. S. N.

Behrman, in a short story that appeared in a recent issue of the

New Yorker, touchingly describes the reaction of one of his char-

acters to such elusive writing:

Reflecting on these miseries, yet struggling also to keep his mind

on the words he was reading, Mr. Weintraub took off his glasses and

polished them again. Because his fonnal education had been sketchy,

he did not know that he had a right to demand clarity and simplicity

from an author, or that the relationship between writer and reader

was a reciprocal one and the responsibility for understanding divided

equally between them. He cursed himself for being stupid, and he

felt a certain pride that for [his son] Willard, presumably, these mas-

sive and coagulated paragraphs were hammock reading.

Regressions, then, are by no means forbidden

—

if they are abso-

lutely necessary. When you have an impulse to regress, test your

needs against reality. Ask yourself, have you really not understood

what you have just read, or are you merely indulging a had habit?

Is it positively essential to check up on that word, or phrase, or de-

tail you don't feel too sure of, or can you go on notwithstanding,

and with no great loss? Try this a few times and you may be sur-

prised to discover that regressions are seldom as vital as they may

at first seem. Try building up the habit of constantly reading for-

ward so long as comprehension is not totally impossible—again

you may be surprised to discover, if you have the courage to take

the gamble, that your understanding is better than you give it credit

for and does not need frequent checking up on!

91](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-113-2048.jpg)

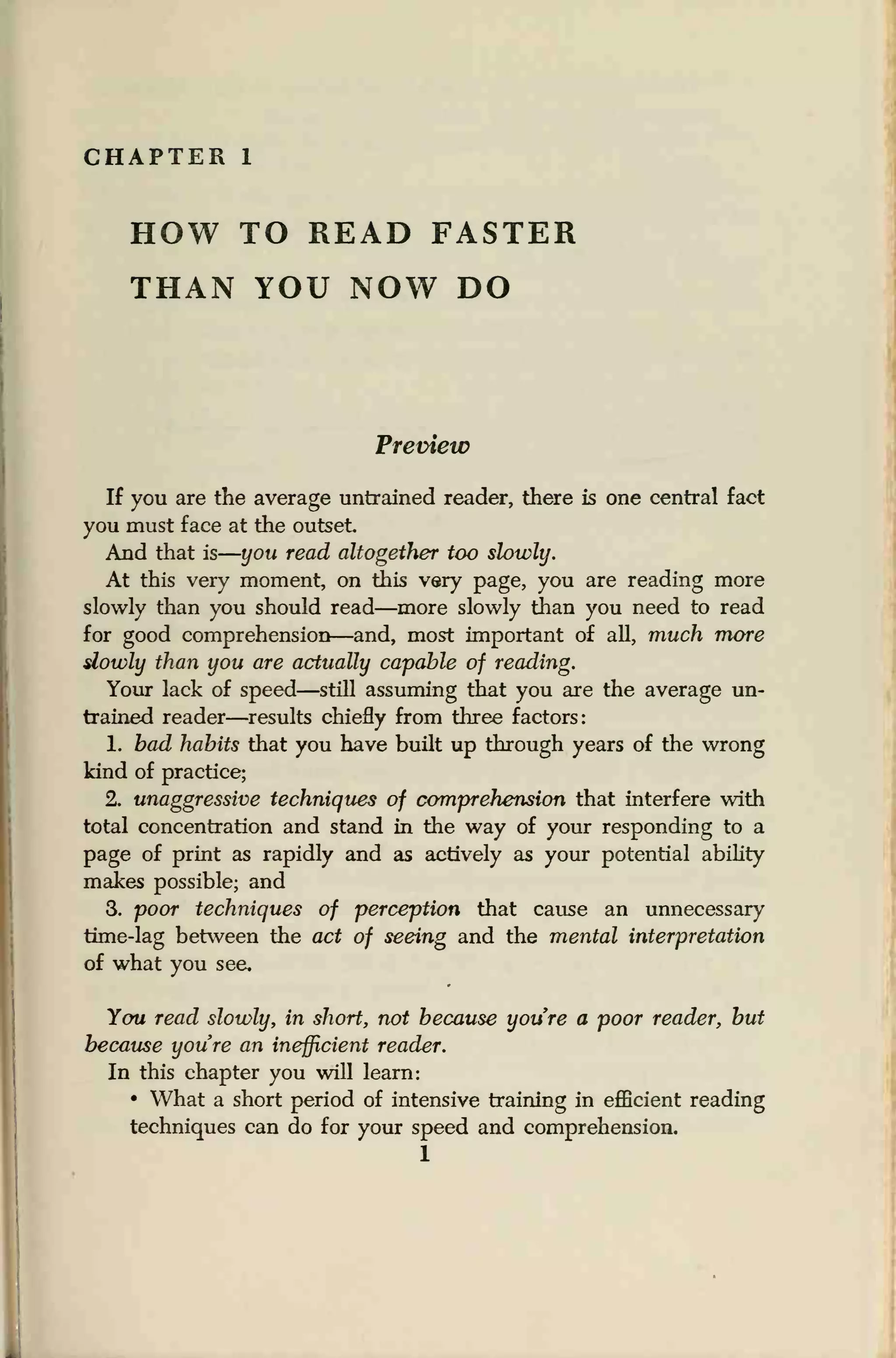

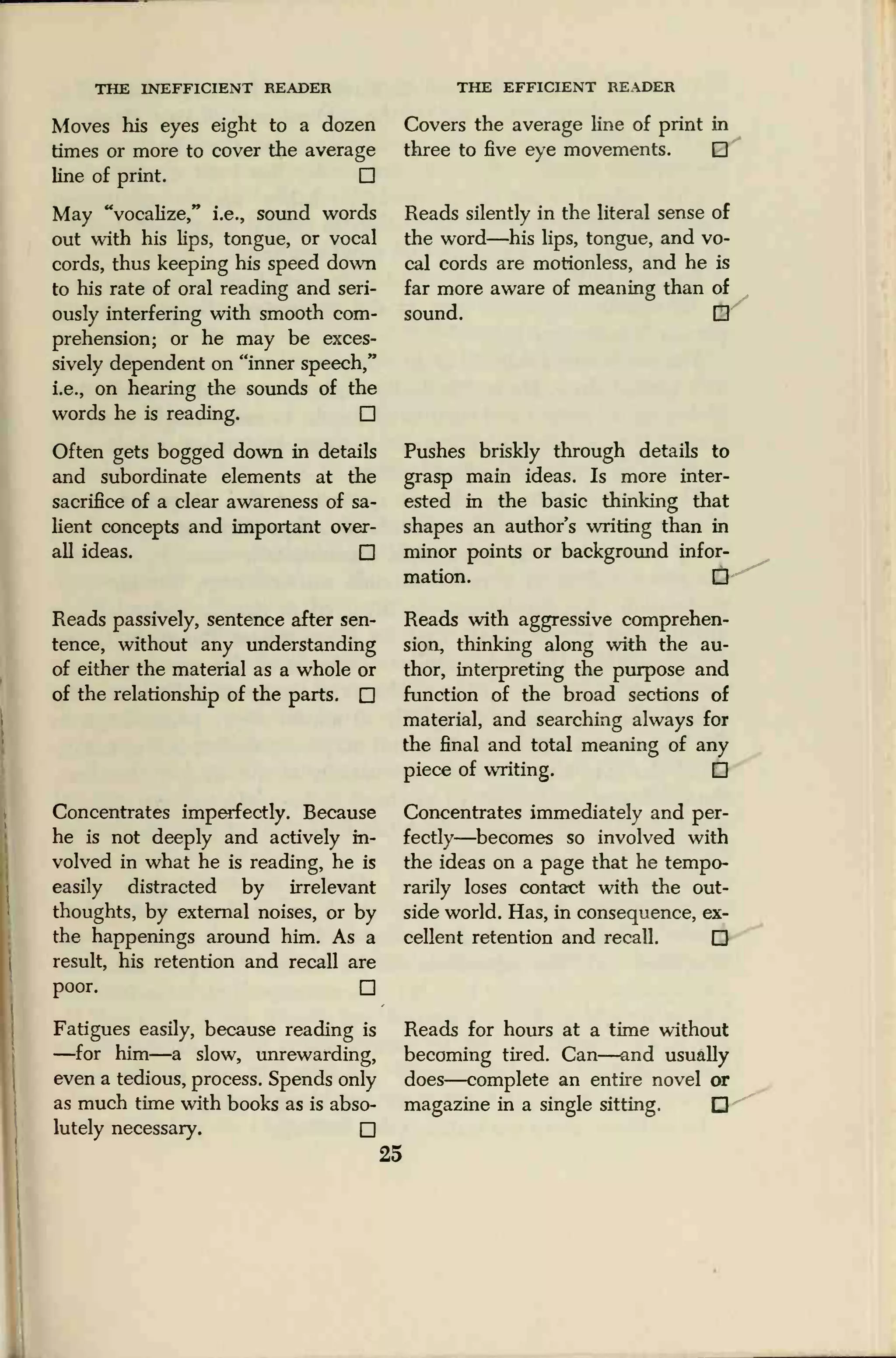

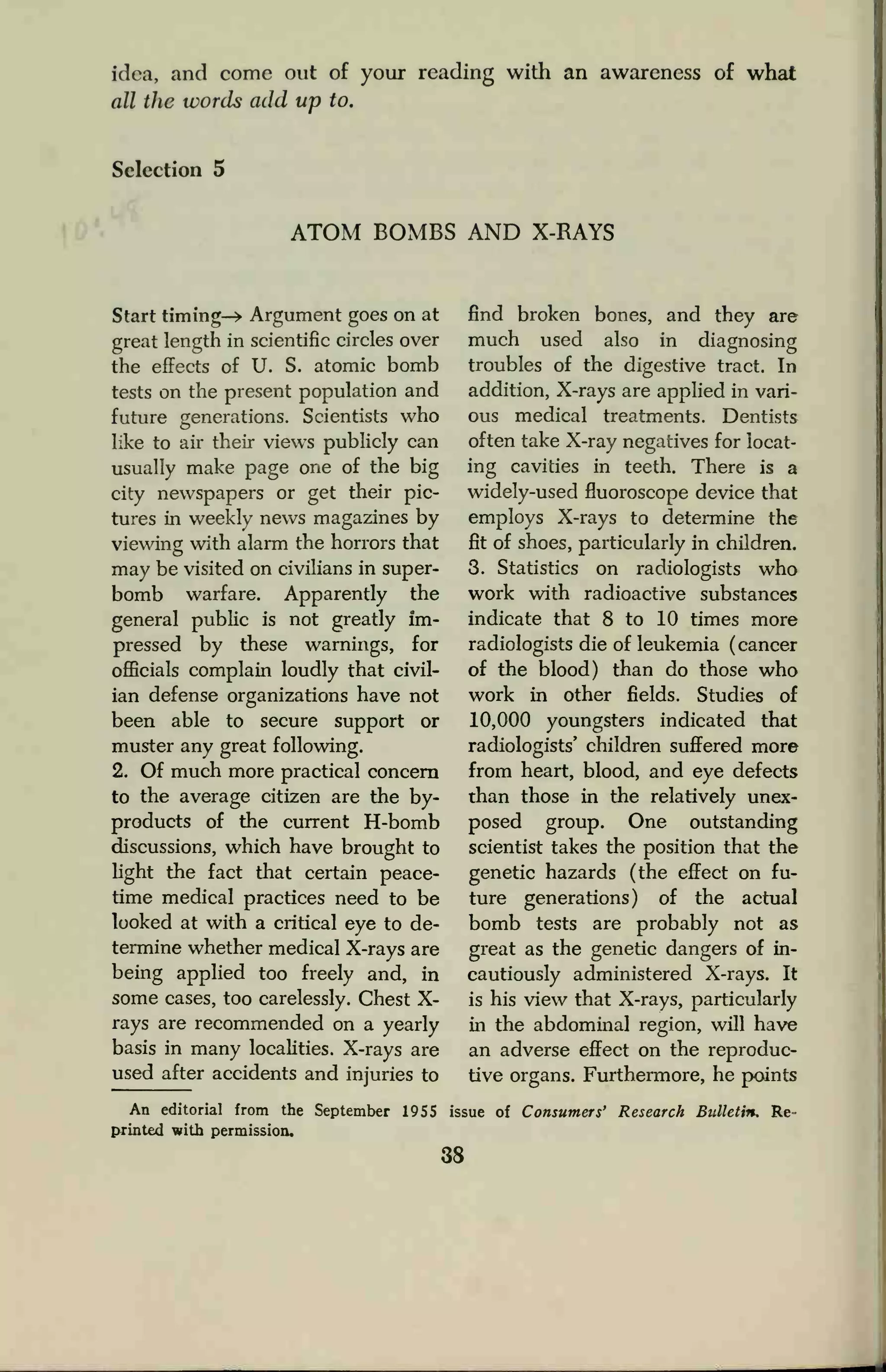

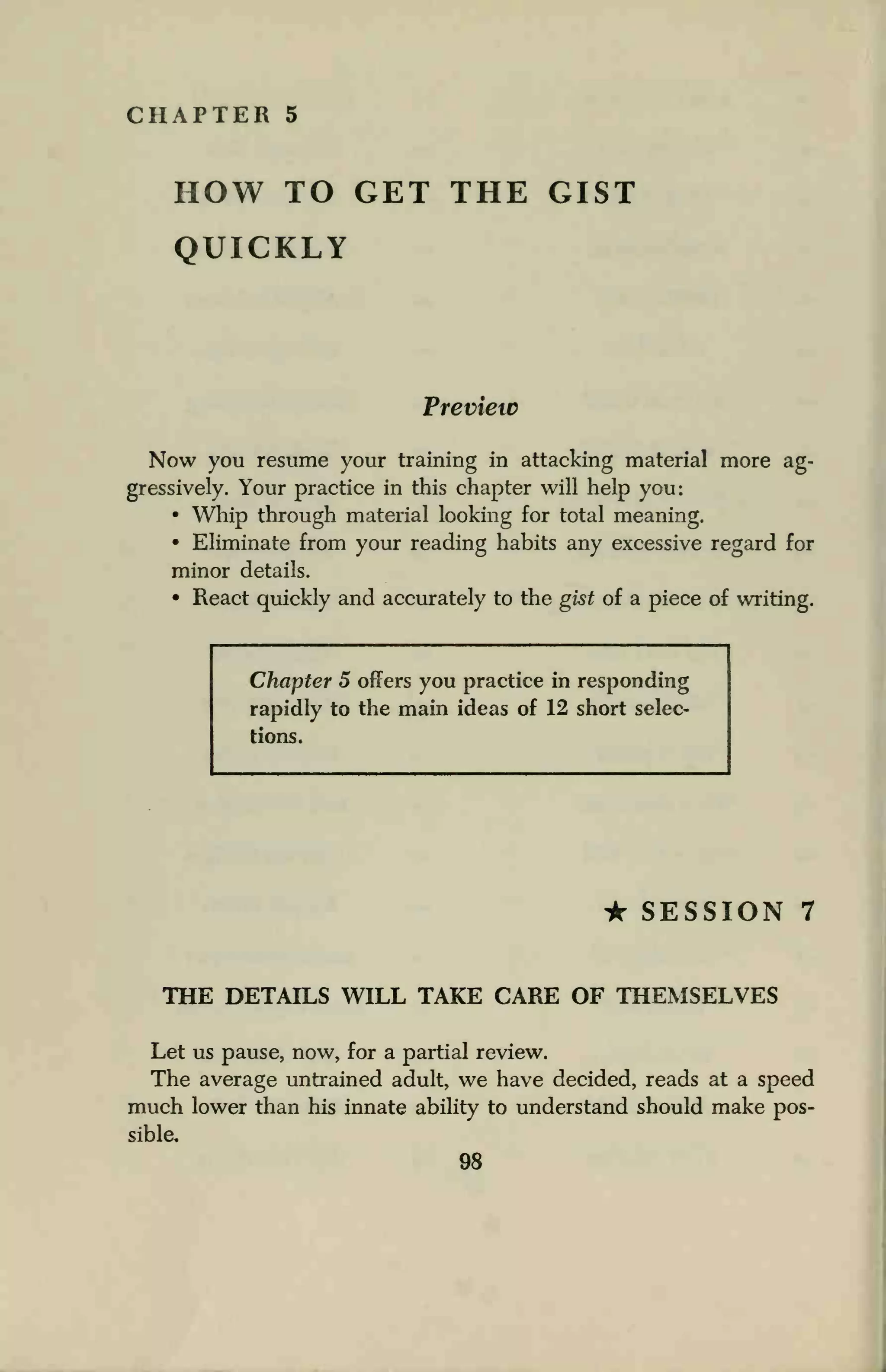

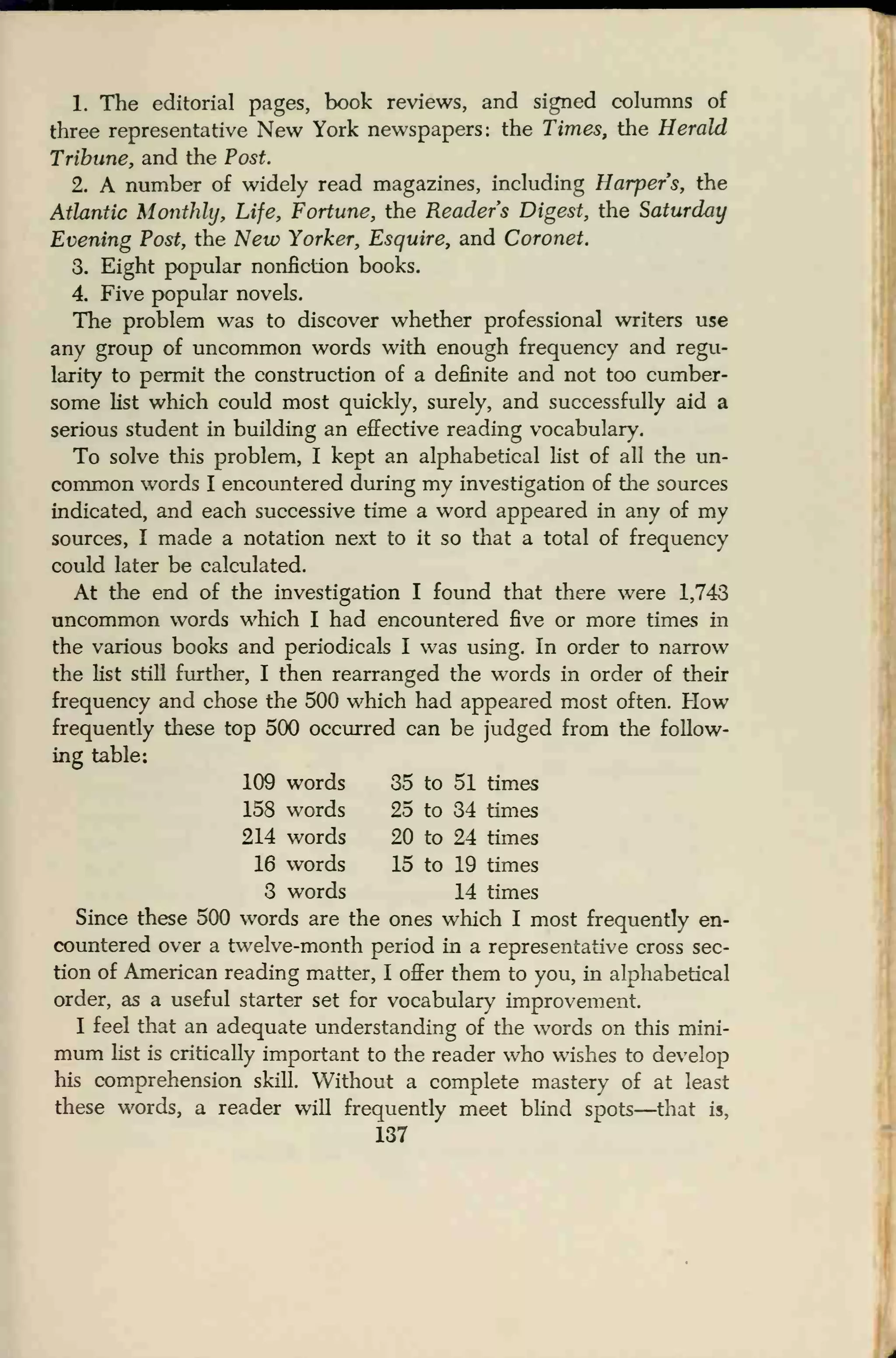

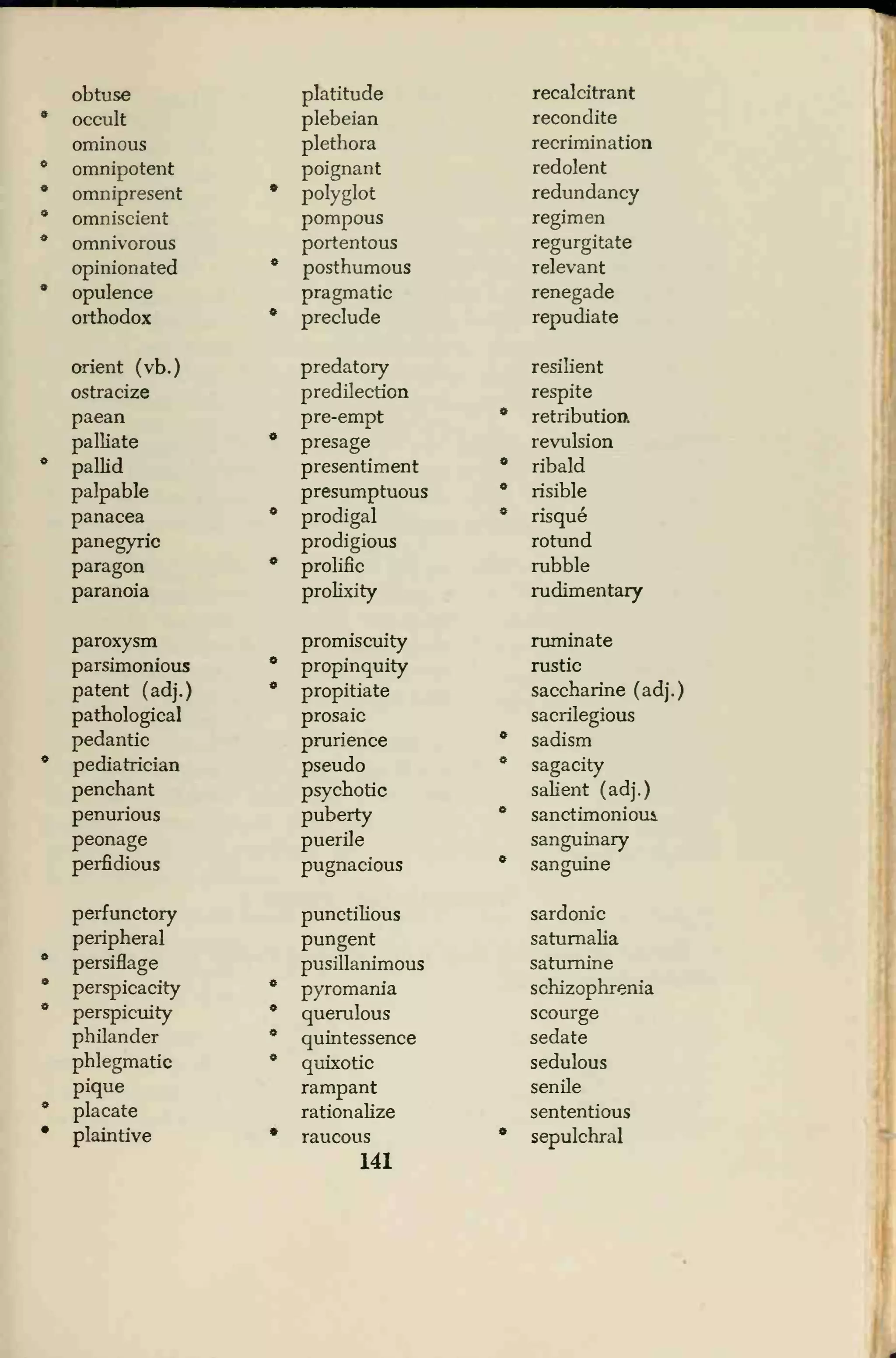

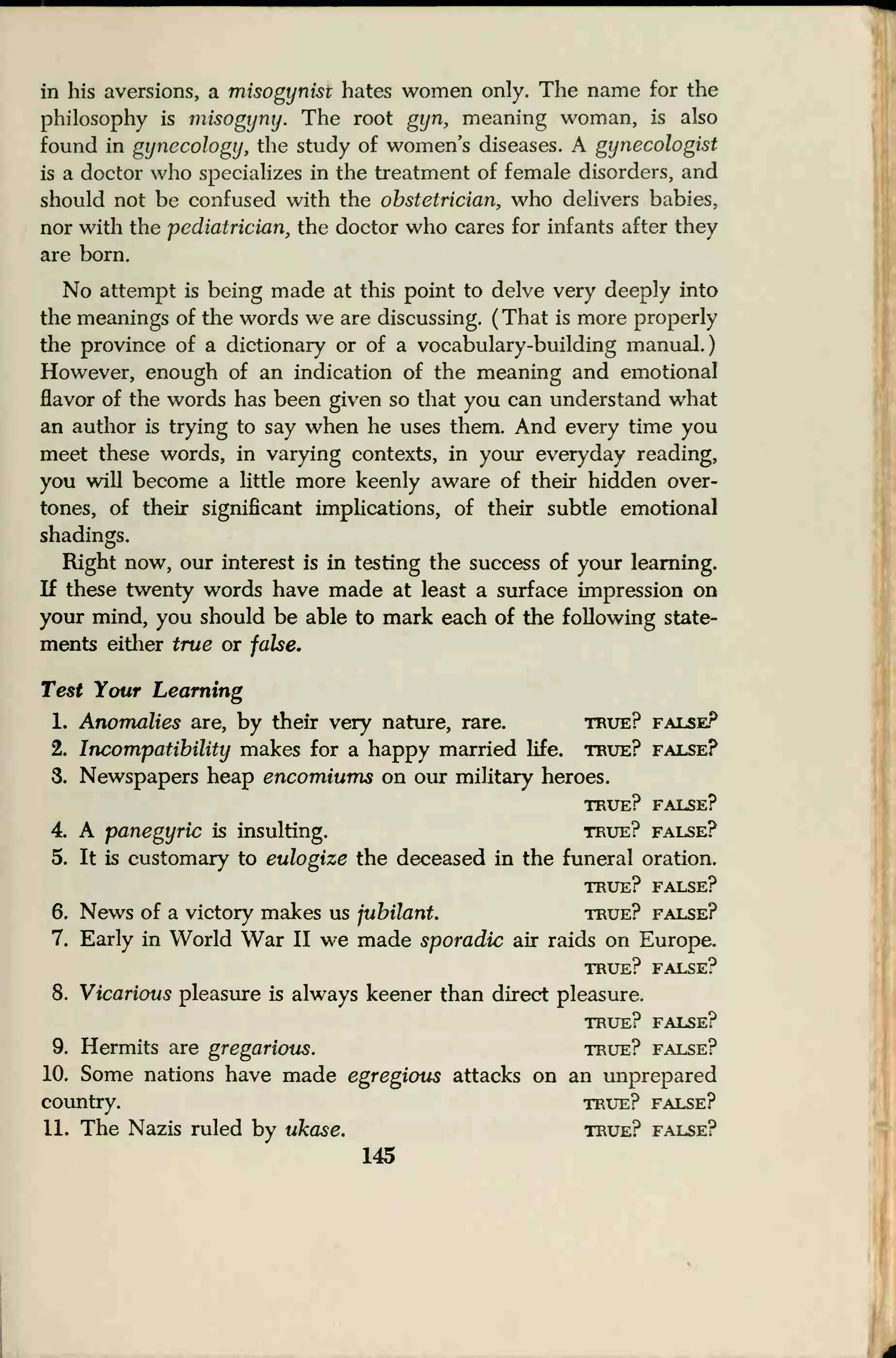

![12. Captiousness often creates resentment. true? false?

13. Misanthropy is a widely held philosophy. true? false?

14. Kind people are usually philanthropic. true? false?

15. Anthropology is the study of insects. true? false?

16. Fish are anthropoid. true? false?

17. Casanova was a misogynist. true? false?

18. A gynecologist is a woman-hater. true? false?

19. An obstretrician treats young infants. true? false?

20. A pediatrician is a foot doctor. true? false?

Key: 1—T, 2—F, 3—T, 4—F, 5—T, 6-T, 7—F, 8—F, 9—F,

10_T, 11—T, 12—T, 13—F, 14—T, 15—F, 16—F, 17—F, 18—F,

19—F, 20—F.

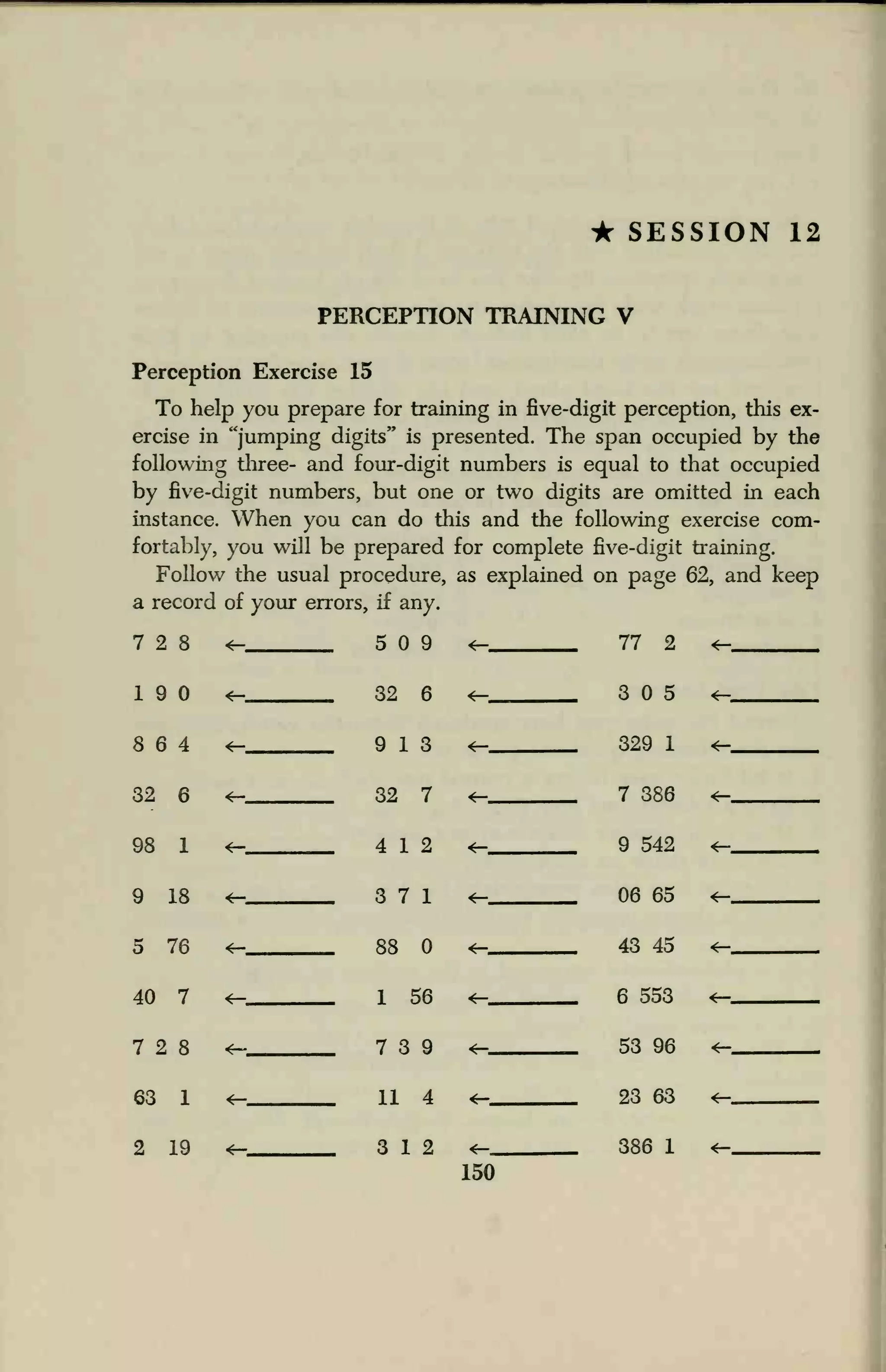

We have, as I have indicated, so far only scratched the surface

of these 20 valuable words. Now I ask you to dig a little deeper,

using a good dictionary as a help.

(If you find your present dictionary inadequate in any way, I

suggest any one of these, which are among the best published today:

1. Webster's New World Dictionary, College Edition [World

Publishing Co., $6.75 thumb-indexed]

2. American College Dictionary [Random House, $6.75 thumb-

indexed]

3. Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary [G. & C. Merriam Co.,

$6.00 thumb-indexed]

4. Thorndike-Barnhart Comprehensive Desk Dictionary [Double-

day and Co., $3.50 thumb-indexed]

With the dictionary as your guide, you will make a concerted

attack on these words. Here are the first ten, in alphabetical ar-

rangement—look each one up, find the information that will help

you answer the questions below, and write your answers either in

the margin of the page or on a scratch pad, or, if you wish to keep

your vocabulary-study in a more permanent form, in a bound note-

book.

1. anomaly

a. First, read and understand the nontechnical definition. Then, in

your own phraseology, write briefly the general meaning of the

word.

b. Write two forms of the derived adjective, which you will find

either with the word or in preceding entries.

146](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-168-2048.jpg)

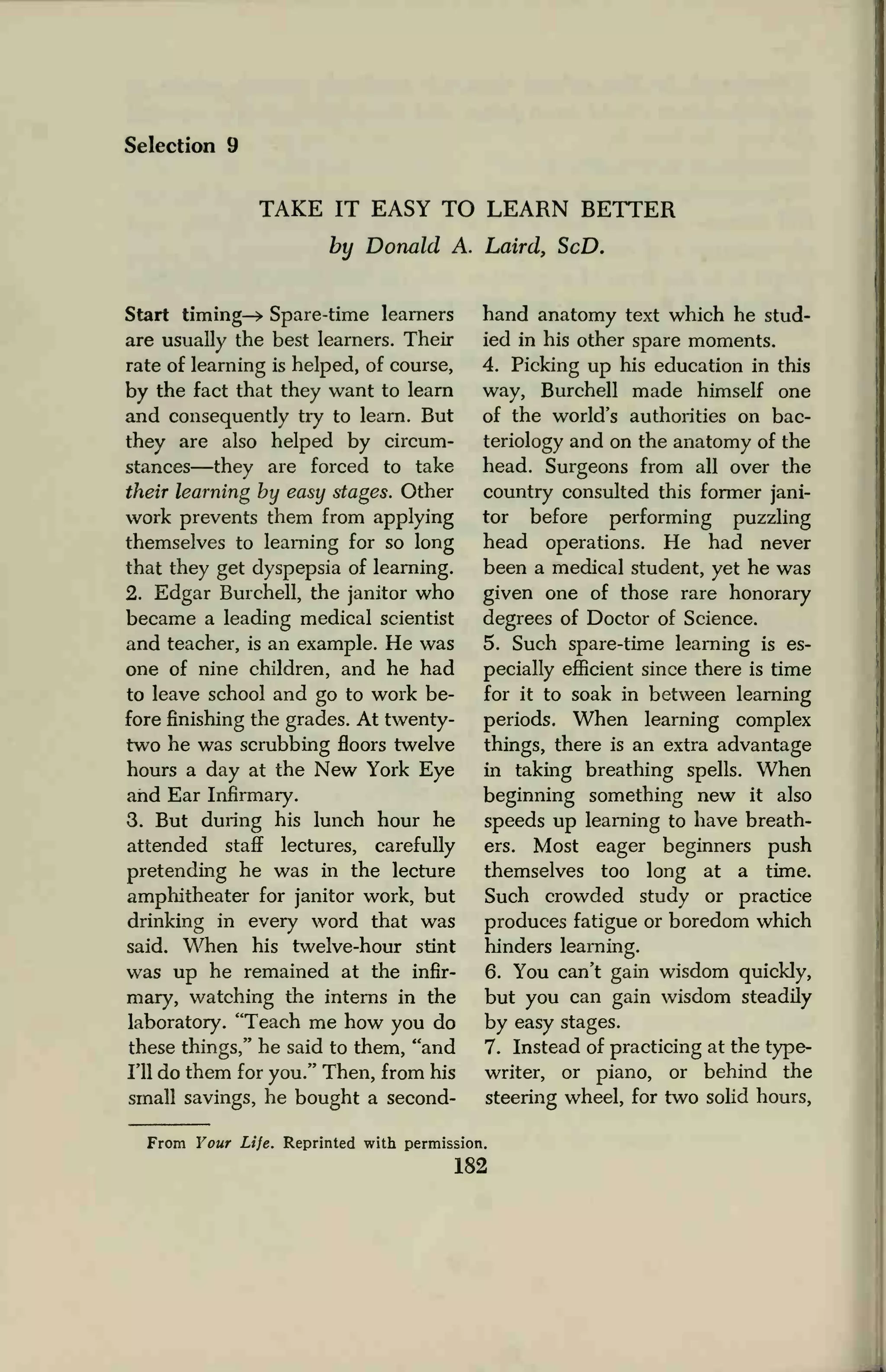

![In paragraphs 1 through 9, the author explains in elaborate detail

the first of these principles

—

for best results space your learning and

practice, i.e., take your learning in easy stages, etc. For the next

four paragraphs (through 13), he offers and enlarges on his second

suggestion

—

keep a record of your progress. In paragraphs 14

through 21, he calls for overlearning; then, through paragraph 30,

he describes four broad types of learning and suggests that you

"use your head along with . . . [or] more than your hands."

Finally, in the last two paragraphs, he sums up, under seven

headings, the four major principles around which the article is

built.

Correct choice on the comprehension test is statement 1.

Selection 10

WHAT IF I DONT GET MARRIED?

by Virginia Hurray

Start timing—> They tell me I may

never marry. It's a matter of cold

fact that women are outnumbering

men and that there just aren't

enough unmarried men today for

all the eligible women.

At 27, I am amply forewarned

by statistics that my dreams of

marriage may never come true.

Nevertheless, I can face the pros-

pect of middle-aged and old maid-

enhood with something like indif-

ference.

presented with too much gloom

and foreboding.

The authors of articles on the

man shortage (have you noticed

that they are invariably men?) are

altogether too distressed and ap-

prehensive about the unmarried

female. They fear loneliness and

frustration among unclaimed

will lead to wholesale

other women's hus-

II

I'm glad to have been exposed

to the statistics: it's good to know

what the score is. But I am con-

vinced that the statistics are being

From Look. Reprinted with permission of the Cowles Syndicate. Miss Hurray is &

feature writer for the Youngstown, Ohio, Vindicator.

187

women

snatching of

bands.

Rubbish, I say to these worries!

They insult the integrity of women

and belittle all the efforts that par-

ents, pastors and teachers made

in our childhood to fill us with the

determination to lead moral and

useful lives. They are based on the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-209-2048.jpg)

![fice." The officials, of course, to be

the judges.

Some municipalities, too, are ex-

tremely shy. Chicago's policeman

censor systematically eliminated all

reference to gangsters ever com-

ing from there (including a movie

about mobster Al Capone). Jersey

City cut a film in which a plane

pilot remarked, "We're approaching

Jersey City—I can smell it." And

Kansas banned a movie in which a

teletype flashed: "The criminals

were last seen in Kansas City." One

public-spirited scissorman clipped a

sequence in which a counterfeiter

boasted, "My bills are as good as

the originals/'

It got so hard to please every-

body that Samuel Goldwyn re-

marked, "I'd like to make a movie

of 'Beverly of Graustark' if I could

only be sure some mythical king-

dom wouldn't complain!"

Many have tried to get into the

censoring act—for personal, pride-

ful, patriotic, political, propagandis-

ts, moral, social, racial or theologi-

cal reasons. Almost everybody be-

lieves he is specially qualified to

advise, revise and edit movies—not

only for himself and his group, but

for the public as well.

Spain's church-dominated censor

banned "Gentleman's Agreement"

because "It is poison [to say that]

a Christian is not superior to a Jew."

And Jewish organizations tried to

ban "Oliver Twist" because the vil-

lainous Fagin was a Jew (no men-

tion of murderer Bill Sykes, who

was not a Jew). Church groups

condemned H. G. Wells' "Shape of

Things to Come" because God was

not mentioned in it. Catholic pres-

sure banned "Martin Luther" in

most of Canada and many other

countries, and tinkered with history

in "The Three Musketeers." In this

film the wily Richelieu was pictured

not as a Cardinal, prince of the

Church, but as an unscrupulous ci-

vilian politician.

It has even come to a point where

censoring the unseen is now an ac-

tuality. In "Seven Year Itch" Tom

Ewell peeks into a photographic

magazine and sees (what the audi-

ence never sees but is led to believe

is) a nude photo of Marilyn Mon-

roe. At Legion insistence after the

film's release, 20th Century-Fox in-

serted a fast flash showing a photo

of Miss Monroe clad in a proper

bathing suit.

Thus the censors reached beyond

the picture and censored the audi-

ence.

Producers and exhibitors frankly

fear to run counter to Legion de-

mands. They risk the loss not only

of patronage of millions of Cath-

olics who have taken the Legion

pledge, but also "punishment" in

the form of picketing and/or boy-

cott of their theatres for periods of

from one week to a year. Most big

movie companies have contracts

with producers guaranteeing that

film product delivered will receive

at least a Legion "B" rating.

Ill

The opposition to censorship is

rooted in the belief that it would

be a dangerous opening wedge for

377](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtoreadbetterandfaster-normanlewis-150703192625-lva1-app6892/75/How-to-read-better-and-faster-norman-lewis-399-2048.jpg)