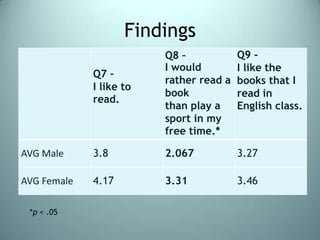

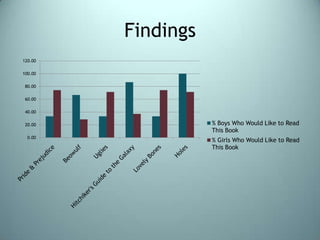

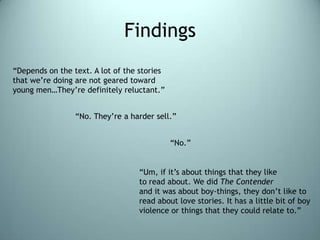

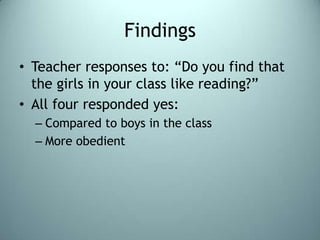

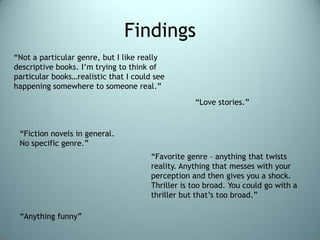

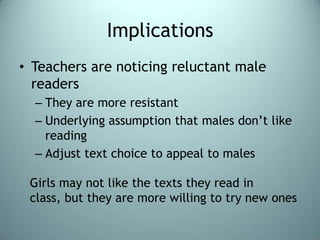

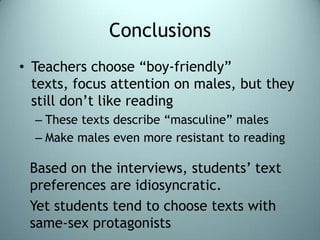

This document summarizes research on the relationship between gender and reading. It finds that while research shows few meaningful differences in reading abilities between boys and girls, teachers and students still view reading as a gendered activity. The study interviewed high school students and teachers and found that teachers choose texts they think will appeal more to boys, focusing more attention on reluctant male readers, and students also tend to choose same-sex protagonists. However, students' individual text preferences varied and were not strictly defined by gender. The study recommends providing more text choice and encouraging students to read across gender boundaries.