Researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology are addressing helicopter blade-vortex interaction (BVI) using computational methods to improve helicopter performance and reduce noise. The study examines the effectiveness of passive devices (spoilers) placed near the rotor tips to diffuse tip vortices, which could lead to enhanced efficiency and decreased maintenance costs. The methodology involves complex simulations that have been validated against experimental data, demonstrating promising results in vortex diffusion.

![Figure 1. One Blade of a Two−bladed NASA Test Rotor

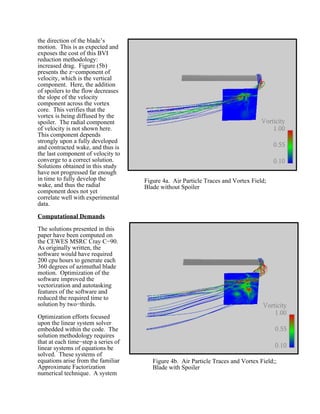

Embedded in a Computational Grid.

Figure 2. The NASA Test Rotor Vortex Field. Rotor

Blades are Colored Grey, Vortex Sheets Blue, and the Tip

Vortices are Colored by the Fluid Velocity Magnitude.

which will be shown in many of

the subsequent figures. The

computational grid about one

blade is an eight−zone

structured H−H−O topology and

consists of 1.2 million points.

The numerical solution

employed in this study is fifth

order accurate in space and first

order accurate in time. The

solver uses a cell−vertex finite

volume scheme in which the

fluid fluxes crossing cell faces

are computed using Roe’s

approximate Riemann solver.

Air turbulence is simulated with

the algebraic Baldwin−Lomax

eddy viscosity model.

Boundary conditions for the

flow variables at the

computational domain’s far field

boundaries are implemented

with high−order extrapolations.

The complete solution

methodology is presented in

Ref. [1].

Results

Figure (2) presents a computed

tip vortex for the NASA test

rotor in hover. In this figure, the

rotor is again viewed from

above. The rotor is moving in

the counter−clockwise direction

at 550 rpm. Computed velocity

components within the vortex

core have been validated against

NASA experimental data

adquired by laser−velicometer

techniques. The computed

solution has been found to

adequately model the vortex.

Ref. [2] examines the

correlation of the present data

with the NASA experimental

data in detail.

The objective of this work is to

diffuse the tip vortex by placing

a spoiler (a tab) at the blade’s

trailing edge near the blade tip.

Analytical studies have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/helicopterrotortipvortexdiffusion-190518171317/85/Helicopter-rotor-tip-vortex-diffusion-2-320.jpg)