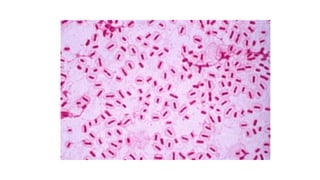

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative rod that causes gastritis and peptic ulcers. It attaches to gastric mucosa and produces urease, leading to mucosal damage. Infection is acquired through person-to-person transmission and is diagnosed via biopsy staining, cultures, antigen tests, or antibody tests. Treatment combines antibiotics and acid reducers to eliminate the bacteria. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen of hospitalized patients that causes infections via virulence factors like endotoxin and exotoxins. It is found in soil, water, and moist areas. Haemophilus influenzae can cause sinusitis, otitis media, pneumonia, and meningitis