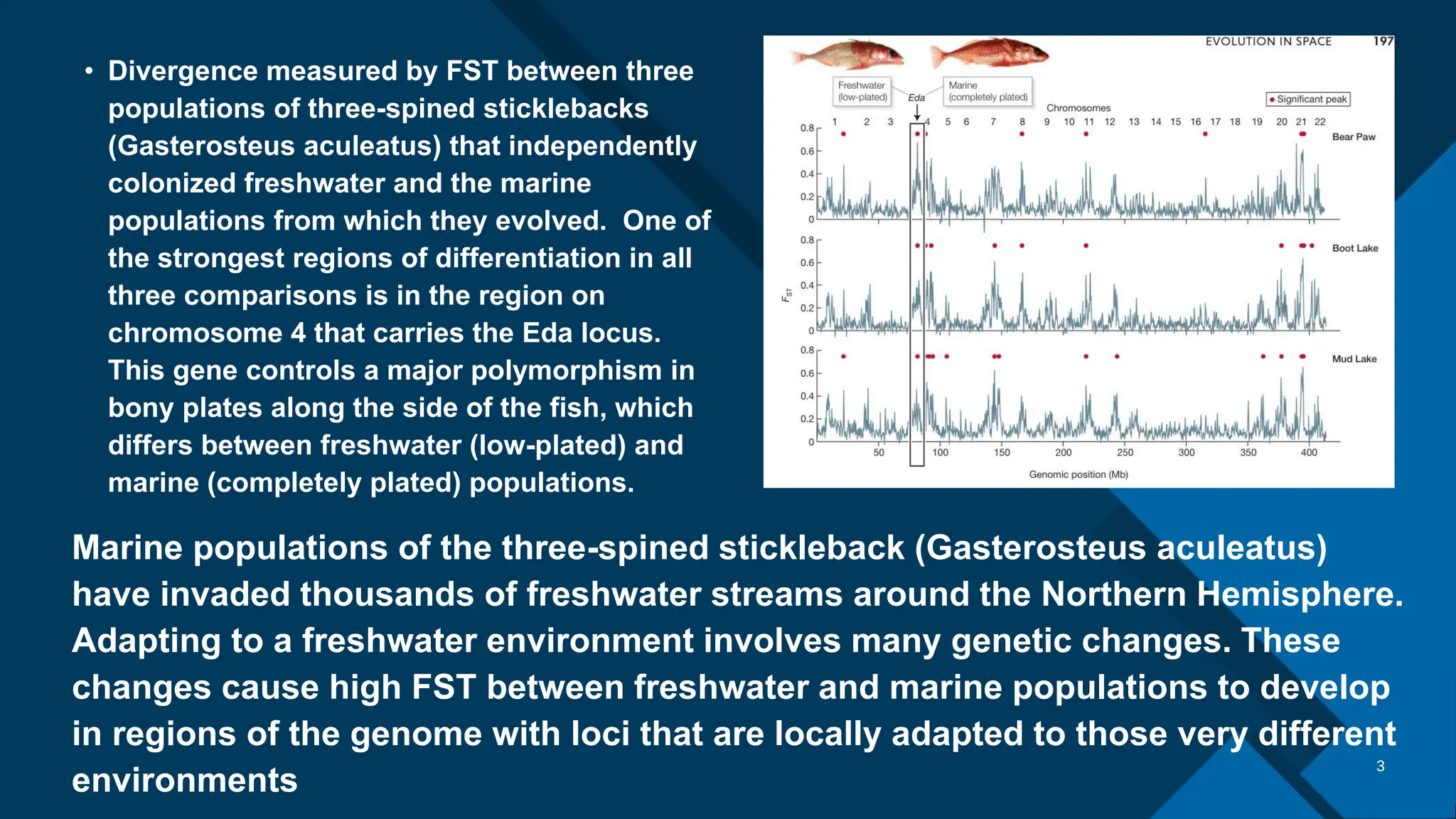

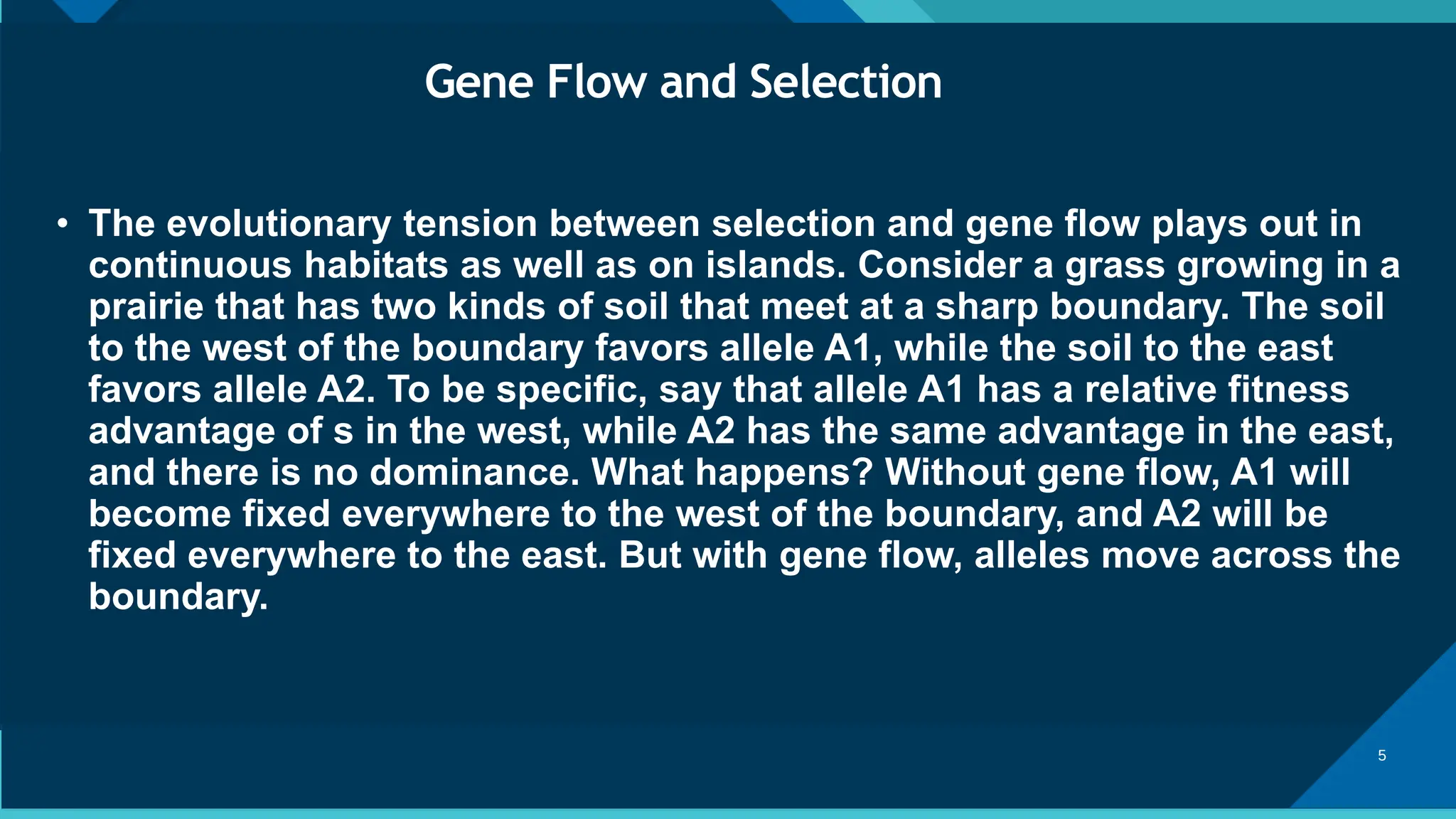

The document discusses genetic divergence between populations, primarily using the statistic FST to measure genetic differences. It emphasizes the low genetic differentiation in humans, with only 12% of variation attributed to population differences, and illustrates various ecological and evolutionary factors, such as isolation-by-distance and the impact of selection versus gene flow on genetic variation. Additionally, it highlights examples from different species to demonstrate how environmental adaptation influences genetic divergence.

![Click to edit Master title style

‹#›

3

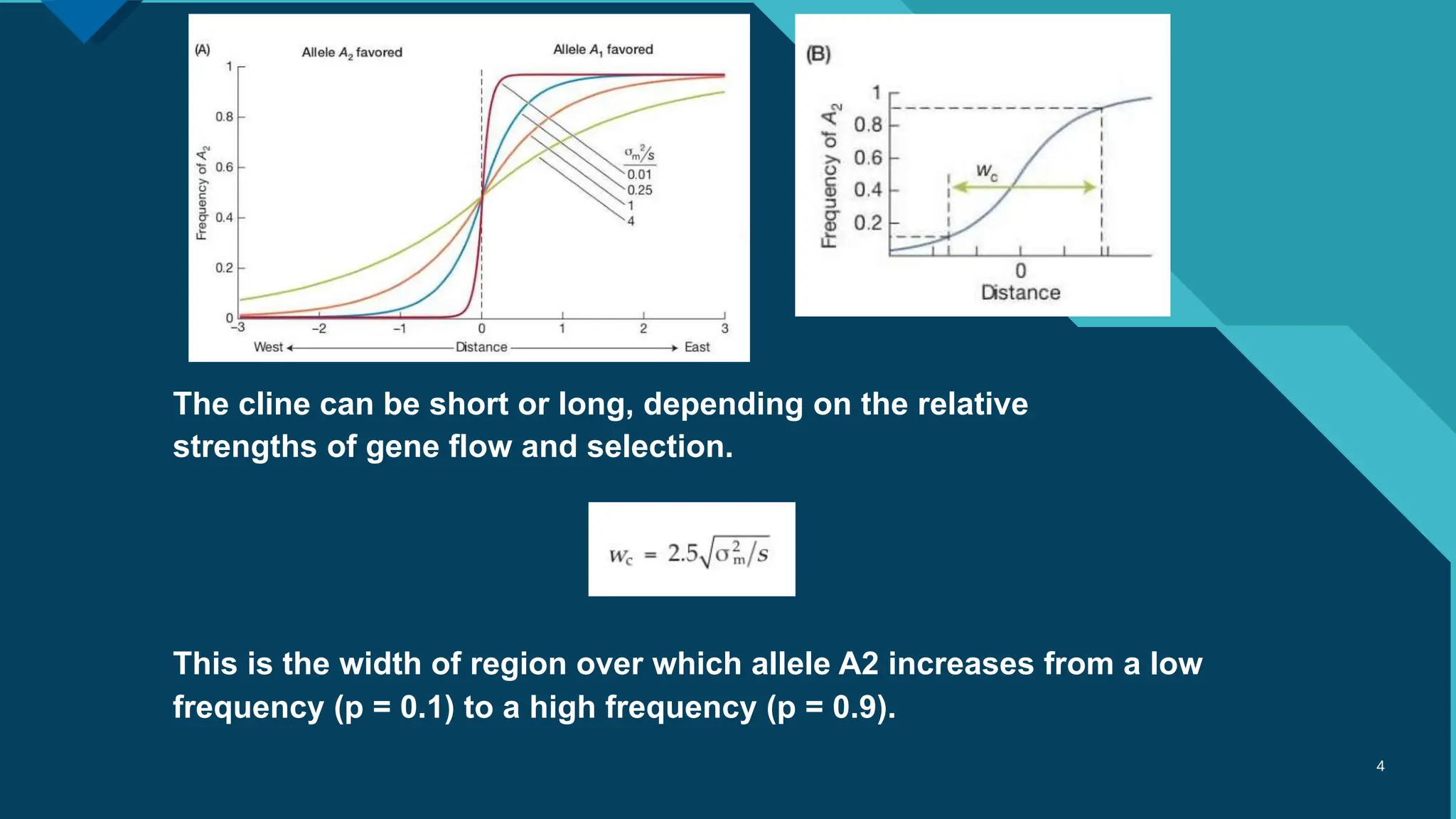

• Isolation-by-distance in human

populations. The horizontal axis has

been corrected for large bodies of water

that could not be crossed when humans

first spread across Earth. The vertical

axis gives FST estimated from 783 loci.

Each dot represents a comparison

between a pair of populations from the

indicated region(s).

ISOLATION-BY-DISTANCE

In humans, it reflects the history of how we colonized different parts of Earth. A similar pattern can

also result from a balance between gene flow and random genetic drift. In other species, the

picture of genetic differentiation is quite different. Populations of the northern dusky salamander

(Desmognathus fuscus) living near New York City have FST values more than four times larger

than those in human populations spread across the entire planet [23]. The contrast between the

relatively low values of FST in humans and the high values in the salamander underlines the point

that simple measures of genetic similarity cannot be used to determine which populations do and

do not belong to the same species.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/titlehere-240507132040-555e3e9f/75/genetic-Divergence-between-population-pptx-5-2048.jpg)