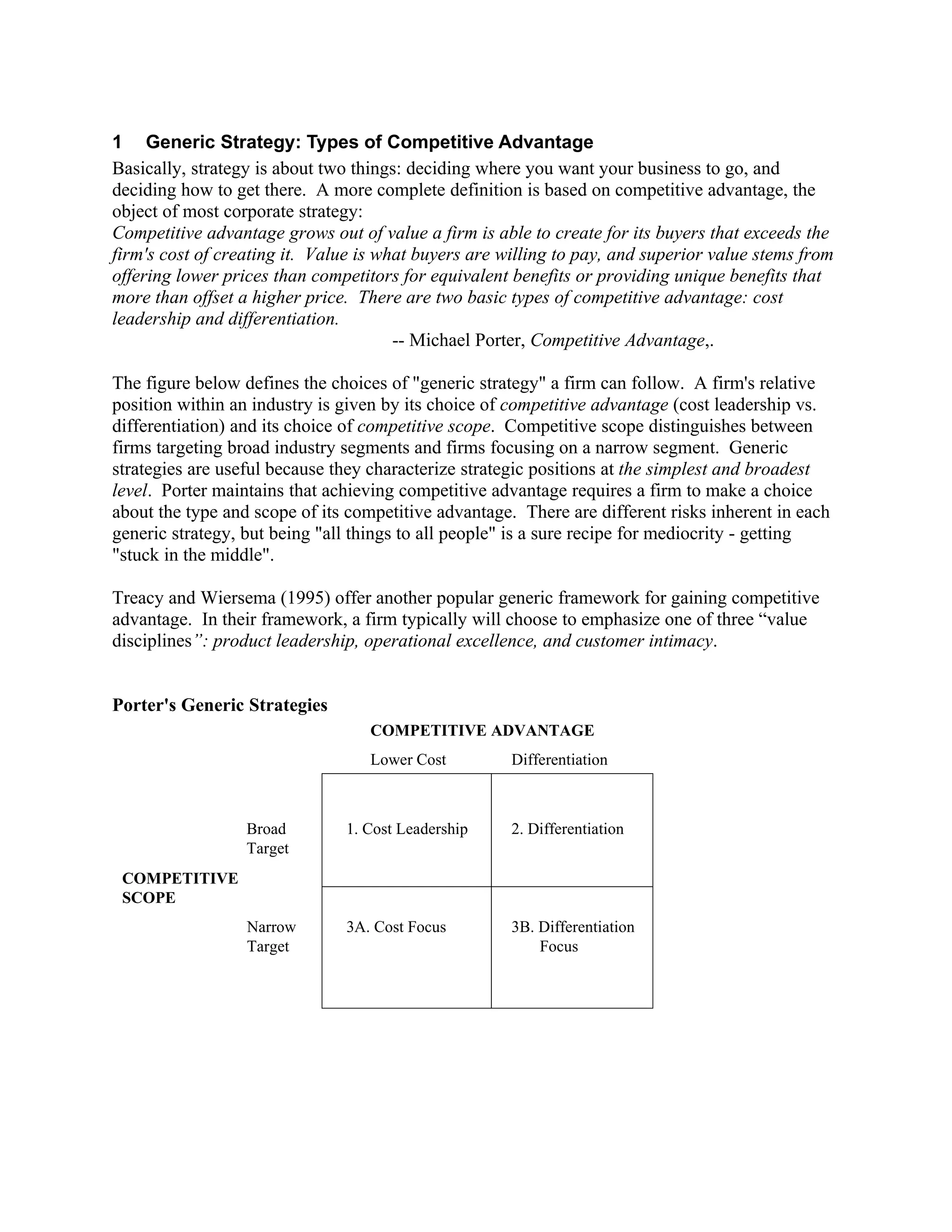

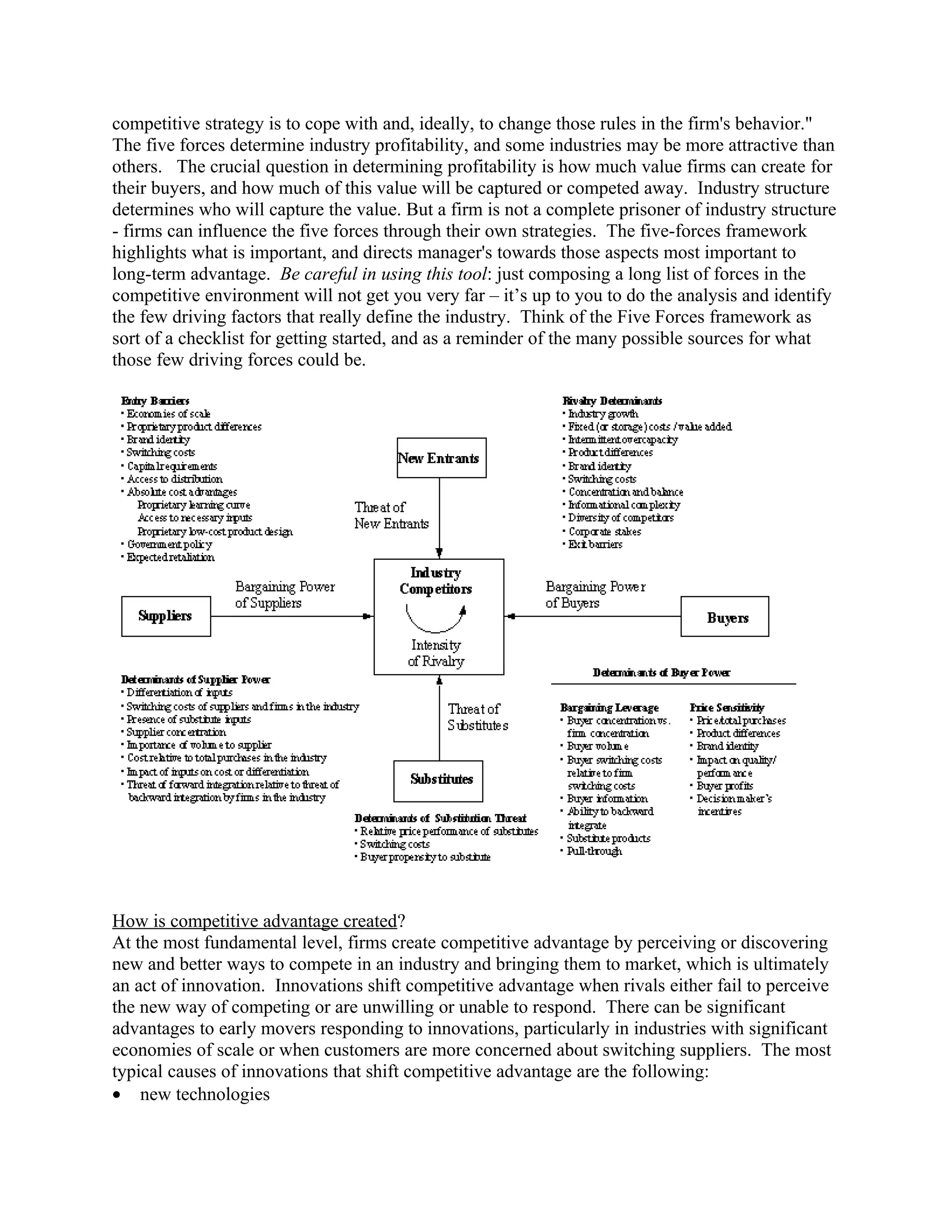

Porter's generic strategies framework outlines three types of competitive advantage - cost leadership, differentiation, and focus. Firms can pursue one of these advantages across a broad or narrow scope. Competitive advantage is created through value chain activities that are difficult for competitors to imitate. It is sustained through durable sources of advantage, multiple distinct sources, and continuous upgrading. Alternatively, the core competence framework emphasizes developing dynamic capabilities rather than positioning within an industry. Core competencies allow firms to enter new markets and are sustained through continuous investment. Both frameworks provide guidance for analyzing competitive advantage but must be tailored to a specific company's challenges.