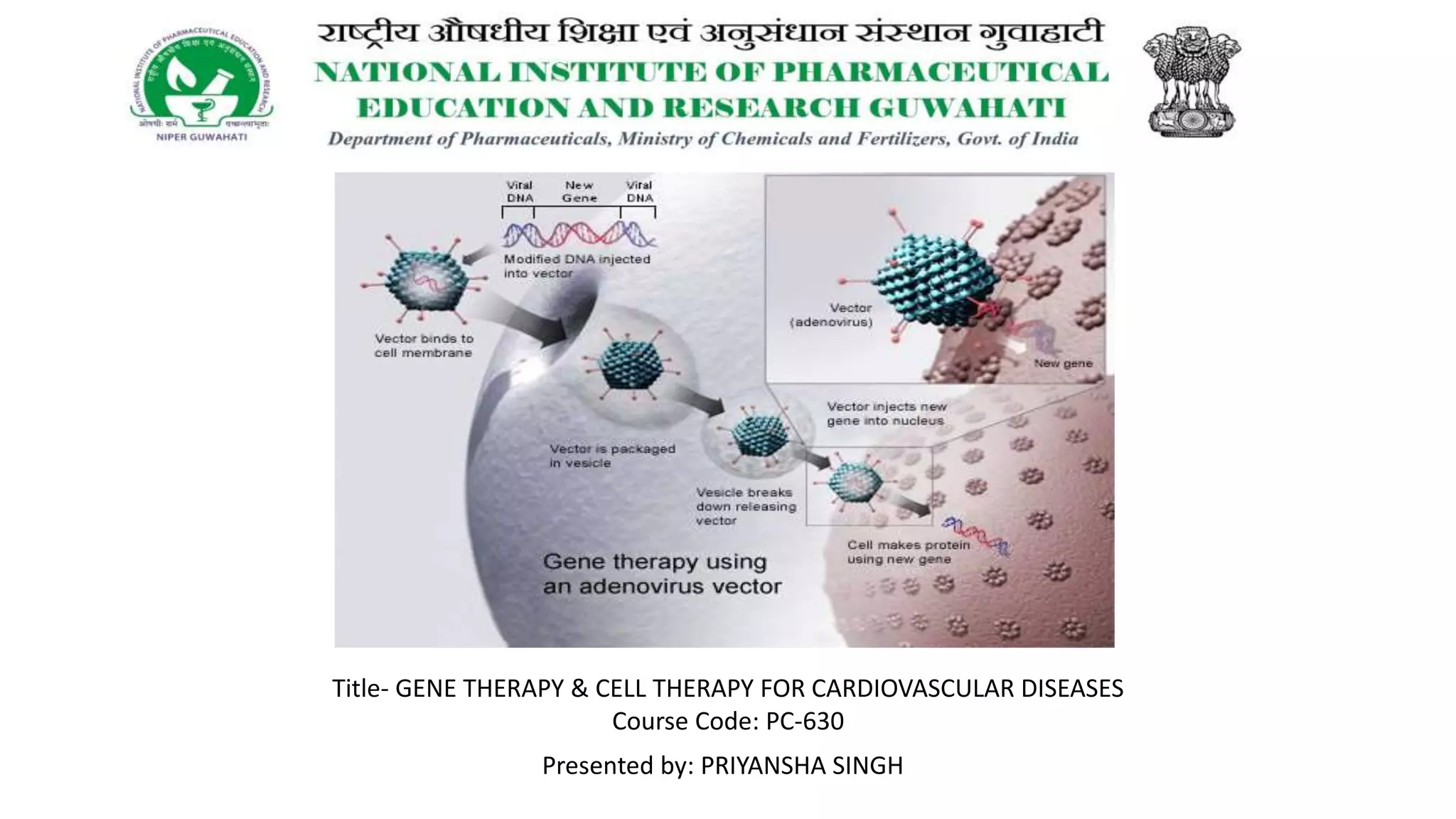

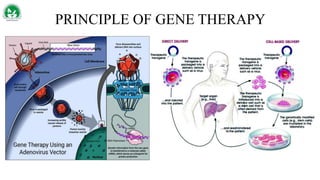

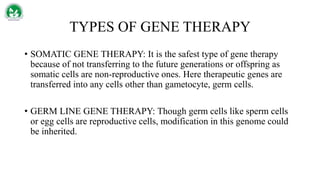

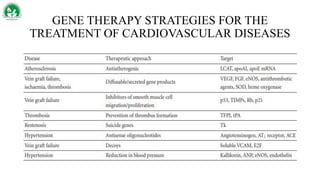

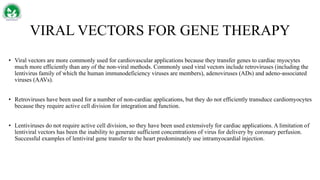

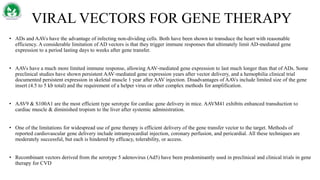

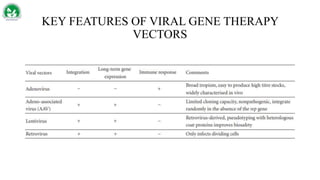

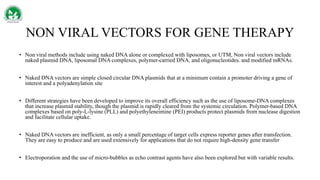

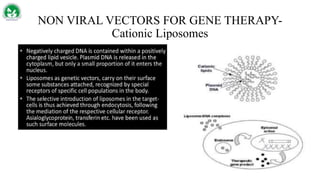

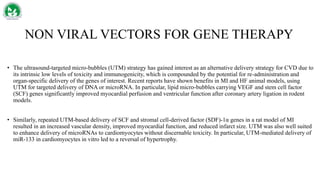

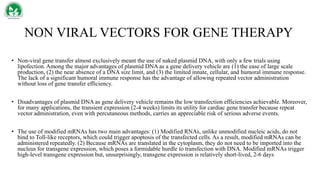

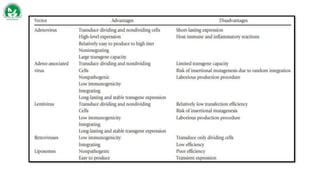

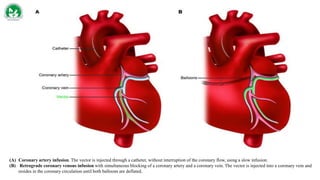

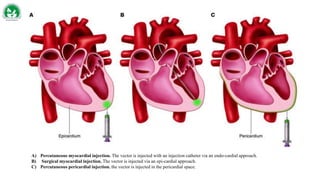

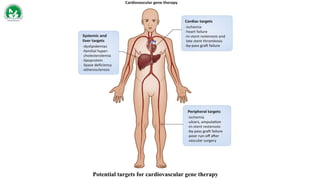

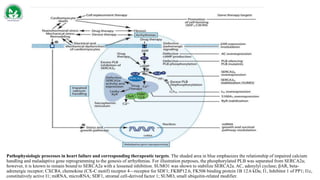

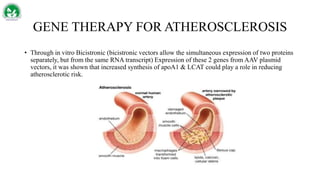

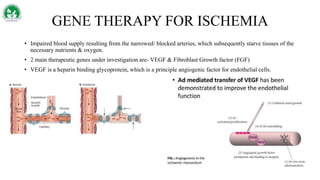

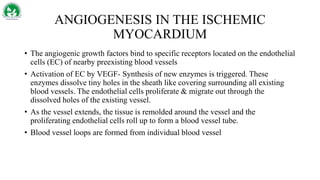

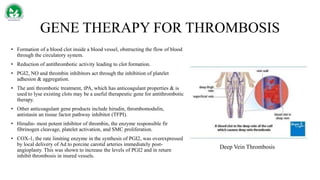

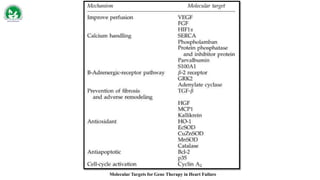

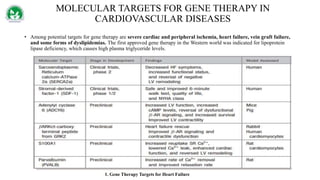

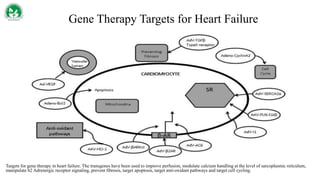

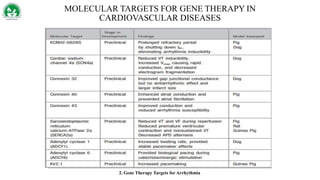

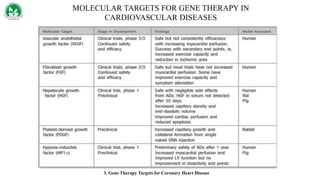

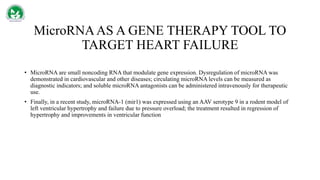

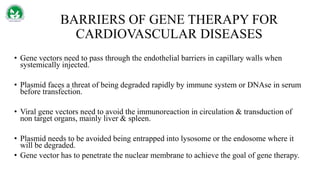

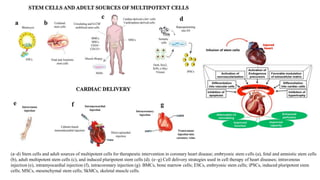

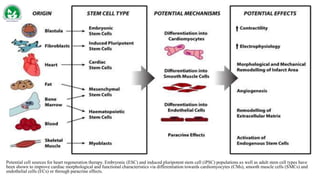

Gene therapy and cell therapy hold promise for treating cardiovascular diseases. The document discusses gene therapy strategies using viral and non-viral vectors to target conditions like heart failure, atherosclerosis, and ischemia. Key molecular targets discussed for heart failure include SERCA2a, SDF-1, and genes involved in calcium handling. Challenges for cardiovascular gene therapy include developing efficient methods for delivering gene vectors to target tissues.