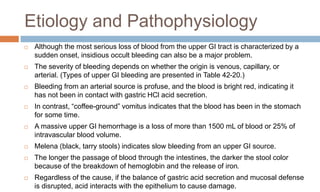

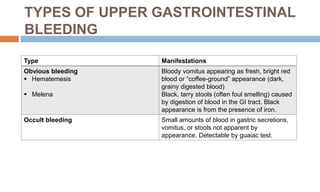

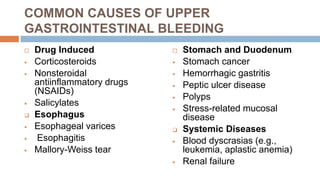

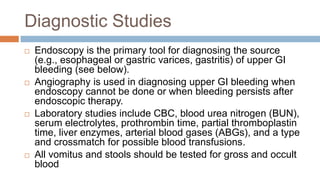

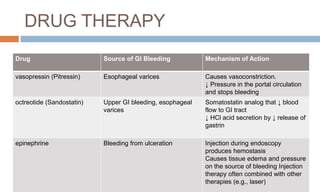

This document provides an overview of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including its causes, types, diagnostic studies, treatment options, and nursing management. The main causes of upper GI bleeding include drug use, esophageal varices, esophagitis, peptic ulcers, and stomach or duodenal cancers. Diagnostic studies involve endoscopy to identify the source of bleeding. Treatment may involve endoscopic therapies, drugs to reduce bleeding, or surgery in severe cases. Nursing care focuses on emergency stabilization and monitoring for signs of ongoing bleeding or complications.

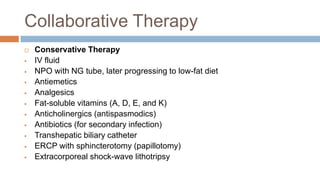

![Collaborative Therapy

Dissolution Therapy

ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall])

Surgical Therapy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Incisional (open) cholecystectomy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gastrointestinalbleeding-230320091329-8dc37293/85/Gastrointestinal-BLEEDING-pptx-24-320.jpg)