Frustrated on the path of nonviolence

- 1. FRUSTRATED ON THE PATH TO NONVIOLENCE ANEC By Dr. Mary Gendler (Psychologist) Chief Resource Person “Everyone wants and needs peace on the earth, so why do people make those weapons of violence?” “If there is no nonviolence, then what will happen to the world?” Composed and edited by Dr. Mary Gendler

- 2. “Frustrated on the path to Nonviolence” REPORT ON ACTIVE NONVIOLENCE EDUCATIONAL SEMINARS WITH STUDENTS THROUGHOUT THE TIBETAN SETTLEMENTS IN INDIA 1995 - 2010 What Tibetan children in India think and feel about the continued use of Nonviolence to further their cause to free Tibet, as well as ideas of how to further economic development and maintain Tibetan culture in occupied Tibet Frustated on the path to nonviolence

- 3. Forward by Dr. Mary Gendler This report is dedicated to the Tibetan exile community in India who, since 1995, with great trust and generosity, has opened its doors to two Westerners wishing to introduce them to new ways of practicing nonviolent struggle. Beginning with His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, and continuing with the Prime Minister, Ministers of various departments including the Departments of Internal and International relations, Security, Education, and Health, we have been greeted with warmth, and aided with organizational help. More specifically, it is dedicated to the wonderful Tibetan students who have vigorously and cheerfully participatedintheworkshops onactivenonviolence. To all of you we say: we admire your commitment to nonviolence, and we admire your determination to maintain your culture, your religion, your distinctiveness, in a world which is fast becoming much too homogenized. Following the path of nonviolence in order to regain your country is a courageous, moral, and smart thing to do, even though the odds are great, and the opponent seemingly invincible. With regards to using violence, one has only to look at the Uighurs, or the Palestinians to see that violence has not succeeded in advancing their cause of freedom. But you should know that even if China succeeds in overwhelming Tibet with Chinese people and Chinese culture, the Tibetan people will never perish. For if you, in exile, follow the advice of one student who counseled, “hold tight to your culture, and never let it go”, just as the Jews have survived in diaspora for two thousand years, so can you! And to what another student said, “nothing can destroy the human spirit”, we say “right you are!” Our work with you and with your whole community has enriched our lives more than you can ever know. In our faith tradition, Judaism, we have an important tenant which in Hebrew is called “Tikkun Olam”, to repair the world. We are all commanded to do our part in this repair. We have been blessed to be able to share our knowledge with you, for we believe that your cause is just, and we admire your efforts to struggle nonviolently. We thank you all for letting us into your community so trustingly. We hope that some of the seeds which we have sown will germinate, and give rise to a successful nonviolent struggle, so that your dreams of returning to Tibet will be realized, and you will, indeed,“becomeablessing.” Frustated on the path to nonviolence

- 4. “Participant observer” is a term first used by social scientists in the 1920's. It refers to someone who, while actively participating in an activity or project, also manages to observe and record some of the history and process of what was happening. It is a rare skill, and the valuable results of its effective practice are impressively documented in Dr. Mary Gendler's revealing report. These findings are derived from more than 15 years during which, for some weeks nearly every year, we have spent time in India introducing the Tibetan exile community to elements of strategic nonviolent struggle, a Western, pragmatic complement to the Dalai Lama's inspiring advocacy of compassion andnonviolence. During this transitional period, the Tibetan exile community faces fresh challenges, both external and internal. All the more important, then, are a clear understanding of the possibilities of strategic nonviolent struggle for the Tibetan cause, together with some sense of the attitudes and questions of the coming generation. The case studies here cited, together with the detailed record of Tibetan students' reactions to these situations, offer to policy makers and concerned individuals invaluable insights into the realities of how young Tibetanstodayregardnonviolence. As for Mary, so for me have these 15 years been a personally compelling experience. For nearly 20 years previously, I offered annually for seniors at PhillipsAcademy,Andover, a college preparatory school, an academic course on Nonviolence in Theory and Practice. To adapt this course for a markedly different set of students living in strikingly different conditions was itself quite a challenge. It was also an opportunity to draw from still earlier years of my involvement with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the civil rights movement, and thewar resistancemovement. Now add to this the privilege of working with Kalon Tripas Sonam Topgyal and Samdhong Rinpoche, His Holiness' Private Secretary Tenzin Geyche, the honor of regular meetings with the Dalai Lama, the opportunity to collaborate with Mary, and now the promised continuity by the Active Nonviolence Education Center (ANEC), the NGO directed by Tenpa C. Samkhar. To see that these personal satisfactions have also yielded this valuable material, so impressively reported and categorized by Mary, fills me with both gratitude and humility for having been granted the opportunity to participate in this tikkun olam, this small effort towards helping the world move a bit closer to its Divine/humanpossibilities. Forward by Rabbi Everett Gendler Frustated on the path to nonviolence

- 5. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Dr.Mary Gendler and Rabbi Everett Gendler are today much loved, adored and revered house hold names in a relatively large segment of the Tibetan community in exile. This spontaneous, deep seated love, adoration and reverence stem from their long standing dedication, support, perseverance, and solidarity for the just Tibetan national cause for which they have left no stone unturned and no string un-pulled for the past over nearly two decades. The Gendlers' contribution to the dissemination, promotion and consolidation of the Tibetan People's just struggle for restoration of their basic human rights, liberty, cultural and spiritual survival remain ever unshakable and undeviating. We derive tremendous inspiration and courage from their steadfast, indefatigable dedication and allegiance in upholding and promoting TRUTH AND NONVIOLENCE in a world torn by deep seatedhatred,animosity,vengeanceandviolence. It was in 1995 that Dr. Mary Gendler and Rabbi Everett Gendler undertook a most memorable and historic ten day trip to Chinese occupied Tibet behind the impenetrable iron curtains. Little did the Gendlers know that this short but real significant ten day trip to Tibet would be a crucial turning point in their life. During their brief stopovers in Lhasa, Shigatse and a couple of other notable Tibetan towns, the Gendlers observed nothing but profound sense of frustration, despair, sadness and shock in the minds of the innumerable Tibetans whom they came across and shared and exchanged innermost feelings and observations pertaining to the then ground reality situation inside Tibet under Chinese occupation – a promised “Socialist Paradise” turned into a veritable “Hell on Earth” ! There were in fact few who literally seemed pushed totheedgeoffeelingthatfaithful,steadfastadherenceand Date: 1st January, 2013Introductory Note by: Tenpa C. Samkhar ( Mr.) (Executive Director – ANEC ) Former Cabinet Secretary for Political Affairs/ Former CTA Health Secretary P.T.O.

- 6. commitment to the path of peace and nonviolence for many painful decades had rather betrayed them in some ways in their struggle to confrontamostrepressive,ruthless,authoritarianregimelikethePRC. As a well experienced and licensed psychologist in the United States, Doctor Mary Gendler could easily sense the precise pulse of the then existing ground reality situation inside Chinese occupied Tibet and also knew where an effective healing resort could be found. Rabbi Everett Gendler – a rare legacy of the internationally renowned Peace and Nonviolence Activist and immortal US Civil Rights leader Reverend Martin Luther King Junior, was always by Dr. Mary Gendler's side as an everundeterred,colossalmoraleboostertoher ! With the gracious support and consent of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the exile Tibetan Cabinet and Parliament, the Gendlers launched a cogent, unflinching program of training Tibetans from all walks of life and backgrounds on Active Nonviolence Strategies which instilled tremendous courage, hope and optimism in the minds of thousands. The Gendlers also played a pivotal role in setting upANEC and today Dr. Mary Gendler and Rabbi Everett Gendler remain untiring, invaluable Chief Resource Persons ofANEC during all majorANEC workshops and openpublicforumdiscussions. In her amazingly revealing and fabulous Report captioned: “FRUSTRATED ON THE PATH TO NONVIOLENCE” Dr. Mary Gendler facilitates a rare and precious insight into the truly inspiring and thought provoking feed backs and questions that she and Rabbi Everett Gendler received from the many young, energetic participants on whose shoulders fall the herculean but noble and sacred responsibility of saving, promoting and consolidating the unique, priceless identities of a distinct nation and a people that today remain on the very brink of total and systematic assimilation and annihilation in the hands of a merciless, repressive and hard line totalitarian regime behind the massive iron curtains. www.anec.org.in | Facebook : Anec Peace Ph.: 01892-228121 Frustated on the path to nonviolence

- 7. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Tableofcontents. 1. Background and format of the program………………….p. 2. Goals……………………………………………………..p. · Students and schools. · Format of the monograph · Format of our teaching · Small group exercises, case studies, activities, and additional questions 3. Trouble in the Hinterlands of China…………………….p. 4. Notable quotations from students……………………….p. 5. Summary of strategies…………………………………. p. · Need for information to get into Tibet. · Exile community and Tibet · How to conduct protest and resistance inside Tibet · Economic Concerns and Economic Non-cooperation · Preservation of language, culture and religion in Tibet 6. Constructive program…………………………………..p. 7. Farmers and Nomads: Problems and solutions…………p. · Health and hygiene on the countryside · Special problems of Nomads · How to preserve Tibetan culture and religion in the countryside 7. Problems in towns and cities…………………………….p. 8. What can students do for their country? ………………...p. · Nonviolent actions and interesting strategies 10. Interaction with Chinese · Should Tibetans have contact with Chinese people? Officials? · If accepted to attend Beijing University would you go? 11. Inside the heads and hearts of Tibetan students…………p. · Worries about Tibet · Dreams of Tibet. If you return to Tibet, how will it look?

- 8. · Pictures drawn by students: Chinese doing something harmful to a Tibetan, and the Tibetan doing something to make them stop. · Stories about a sick person in the countryside 12. Suggestions, evaluations………………………………..p. 13. Summary………………………………………………..p. 14. Appendix…….................................................................p. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence

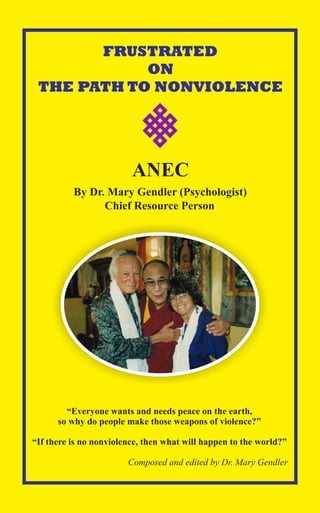

- 9. Gendlers with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1995. Everett Gendler marching with Dr. Martin Luther King in Arlington National Cemetery in 1964 1

- 10. Gendlers and ANEC Executive Director with Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche, Former Kalon Tripa, Feb 2009. ANEC Pilot Training Program for Tibetan Homes Foundation, Mussoorie. Dec 2011 2

- 11. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Background oftheProgram In November of 1995, following a brief trip to Tibet, my husband and I met with H.H. the Dalai Lama to give him a report of what we had seen and experienced in Tibet. Indeed, we had several bad experiences, not with the Chinese, as we had expected, but with Tibetans. The rough, rather rude encounters we had with a group of Nomadic pilgrims on our first day in Tibet, and the lying and cheating which we were subjected to on the part of both of our Tibetan guides (the first dumped us after two days because we were too old!!) and shopkeepers, was quite disturbing. These experiences stood in stark contrast to the almost universally polite, pleasant, interactions which we had had with Tibetans previously in India and Nepal. We were puzzled by these differences, and tried to make some sense out of these encounters.Whyshould thisbeso? As a Psychologist recently retired from clinical practice, I hope I will be forgiven for seeing the situation through those eyes. I had worked with numerous people who had suffered abuse, and they had some deep problems. Given the situation in Tibet, it is not much of a stretch to assume that the ominous, relentless, controlling, and sometimes deadly Chinese presence in Tibet might well be one source of these behaviors. Psychological studies have shown that victims of abuse sometimes become abusers themselves. There is no question that few Tibetans in Tibet have escaped abuse from the Chinese occupiers over the last fifty years, either personally, or through members of their family, friends and neighbors. Having one's country invaded and taken over by another country; having one's cherished institutions (Monasteries) demolished and stripped of art and religious treasures; having any expression of dissent punished with imprisonment, torture and death; having your revered leader forced to flee for his life; having mass emigration of Chinese into your country, now threatening to become the majority; seeing the physical resources of your country raped and stolen; having your schools use Chinese as the basic language; seeing the 3

- 12. best jobs and opportunities go to Chinese; being afraid to go for medical care if you are a woman for fear you will be forced to have an operation to control the number of children you can have; being forcibly resettled if you are a nomad; etc., etc. This list could go on and on. What happens to people when they are put in this position, forced to endure such treatment? It is not too hard to imagine that they will feel anger, frustration, and lack of control over their lives and all they hold dear. These feelings can, and often do, lead to depression, anger, a sense of hopelessness and helplessness, rage, and anti- socialbehavior. Indeed, the situation is only getting worse. To this day, the Chinese exercise iron control over Tibet, and swift action ensues against those who try to resist, violently or nonviolently. The Tibetans there are in a classic double bind. What can they do to make their situation better? The Dalai Lama says that they should not use violence to resist, but the nonviolent actions they have been using have not worked, and they know of no alternative except violence. It is quite understandable they are left feeling impotent, hopeless, enraged and depressed. Under such circumstances, it is not surprising that some begin “acting out” and exhibiting anti-social behaviors. Where are they to place these pent up feelings? How are they to survive under such conditions? Their firm beliefs in the Dalai Lama and Buddhism help a great deal, but it does not give them back their country and their freedom. The obvious next question follows: is there is anything to be done about this situation? Frustrated on the path of nonviolence My husband, Rabbi Everett Gendler, formerly taught at a boarding school, PhillipsAcademy, in the United States.Among the courses which he offered was “Nonviolence in Theory and Practice”. One of the resources he used was the work of a Western sociologist named Dr. Gene Sharp, who offers an active, strategic approach to practicing nonviolence. We thought that perhaps the Tibetans living in Tibet, (also in exile), might feel less frustrated if they had some new nonviolent tools to employ in their struggle against the Chinese. 4

- 13. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Over the course of many years, Dr. Sharp has studied nonviolent actions and movements around the world, and has systematized his findings in an approach which he called “Strategic Nonviolence”. This approach counsels a detailed strategic analysis and assessment of the situation including: sources of power both for the regime to be overthrown and for those struggling against it, an analysis of the economic, social, political situations, and the changes sought. He also includes an element taken from Gandhi's work called “constructive program”, which first analyzes and then lays out a plan for strengthening the community in the areas of education, health, cultural traditions, and work. To all of these ends, he lists almost 200 different nonviolent methods which have been employed in the past, adding that there would be many, many more by now. He also includes case studies of many successful nonviolent revolutions, large and small, around the world. His work has been used in a number of recent democratic uprisings. First, the Serbian students, “Otpor”, succeeded in ousting Milosevic, a truly deadly dictator (the butcher of the Balkans, as he was called). Most recently, the exciting nonviolent revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, are also based on thework byDr.Sharp. Before meeting with the Dalai Lama, we met with Tenzin Geyshe, the Dalai Lama's private secretary.We wanted to find out if our experiences were just a fluke, or whether they might have seen some of the same behavior. Indeed, he told us that many of the young people coming from Tibet were angry and aggressive. He said that they had even been forced to shut down one of the schools where many of them were studying, because of knife fights between studentsfromdifferentprovinces.Therereallydidseemtobeaproblem. At our audience with His Holiness we told him what we had experienced in Tibet, and shared our thinking about why this may have been so. We had already ascertained Dr, Sharp's willingness to come to India to give a workshop if the Dalai Lama requested it. We explained Dr, Sharp's approach to nonviolent action, and His Holiness became quite excited and jumped from his chair and cried “yes, “yes, we must learn more about it!” Thus was 5

- 14. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence born our project which has extended over the past 17 years. Dr. Sharp returned three times to give high level seminars, while we, understanding that nonviolence is a people's movement, began to give seminars and meetingsthroughouttheTibetanDiasporainIndia. Between the years of 1995-2012, at the bidding of the Tibetan exile government, we traveled to almost all of the Tibetan settlements in India to introduce Tibetans to new ideas about how to struggle nonviolently against Chinese occupation in Tibet. We spoke in schools, Universities, Monasteries, Nunneries, community gatherings, merchant groups, women's associations and student associations. We spoke to teachers, administrative staff, veterans, old people, young people, educated and uneducated. In all of this work we were sponsored by the Prime Minister and other high level officialsintheTibetanExilegovernment. Almost everywhere our talks were greatly appreciated, and in their evaluations, many of the students expressed the hope that there could be more seminars on this topic. We would have loved to oblige, but were not able to for several reasons.Amajor structural problem with this arrangement was that the whole program rested on Everett and myself. Although we would come once or twice a year to India and stay a month or two, we needed to come home to our lives and family in the U.S.This was very frustrating for many of our students and for us. As you will see in the evaluations, many, many of them wanted more: more time, more workshops, more information. But since theTibetan administration wanted us to share this information to as wide a group as possible, we seldom went back to the same place twice. Over the years we tried many ways to institutionalize the project somewhere within the Tibet Exile community. We felt strongly that it ought to be a Tibetan led program. Finally, six years ago, we founded of a Tibetan non- governmental organization which is called ANEC – Active Nonviolence Education Center.Ably led by Tenpa Samkhar, a 30 year veteran of the CTA (Central Tibetan Administration), along with a small Tibetan staff, ANEC is continuing and expanding this work in the Tibetan exile community. 6

- 15. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Unfortunately,duetoapaucityoffunding,thework theycandoislimited. Goals One of our goals was to introduce to the Tibetan Diaspora in India, a practical, strategic approach to nonviolent resistance, and to talk about the ways it has been put into practice around the world. Another goal was to provide the Tibetans in India, (with the hope that they would find ways of getting this into Tibet), tools which could enable them to find new ways of resisting the Chinese occupation of their homeland nonviolently, and coincidentally to restore some hope and sense of efficacy in those who so desperately want to preserve their homeland, culture, language and religion. The teaching in the schools which I report on here, was part of a program which we introduced to the broader Tibetan exile community in 1995. We tried to reach as many people in the community as possible. By involving each and every person, and encouraging them to actively participate in the process of trying to regain their homeland, we hope to instill a sense of personal power and responsibility, and as such, we are training them to be activecitizensinaDemocracy. Information intoTibet Obviously, this information needs to find its way into Tibet if it is to be truly useful. Since we are not able to teach this approach to nonviolent struggle there, we must leave it up to theTibetans living in exile to find ways to do this. In India we have tried to focus especially on people who might be going back to Tibet, for they are the ones who can transmit this information. (Unfortunately, crossing the border into and out of China has become increasingly difficult since the Tibetan uprising of 2008). Recently, students in India and in Western countries are increasingly suggesting that Tibetans from exile should return to Tibet and share ideas, skills, information and resources with those who have been suffering under the Chinese occupation. These suggestions are fairly recent, and point to a course of action that the 7

- 16. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence CentralTibetanAuthoritymightwanttopursue. Focuson Students This paper details our work with the Tibetan students, both their questions about this approach to nonviolence, and their ideas about how “Active, Strategic Nonviolence” could be used to improve the situation of Tibetans living in Tibet. I chose to focus on the students because the thoughts and ideas and feelings of the young people are of prime importance.As one of the students said: “The young Tibetan generation must understand that they are the heirs of Tibet.” Most of the students were in grades 8-12. Interestingly, however, some of the liveliest discussions occurred in the occasional th th meetingswithchildrenasyoung as5 or6 grades. The exile Tibetan community is to be congratulated for the astonishing success they have achieved in raising two generations in exile who identify so strongly with their heritage. As you will see from their questions and comments, the children care deeply about their homeland, their traditions and culture, their language, their religion, and their people. The exile government has, with the help of the Indian government, devised a school system which keeps the Tibetan children together, some only in classes, others in boarding schools. This helps to create a solidarity and sense of “people-hood” among the youngsters. How much longer this will continue is, of course, a question no-one can answer. But as you will see, the students are concerned and committed, and it is important that they be given as many opportunities as possible to think about and participate in concrete actions whichwillmakeuse oftheseconcernsabouttheirhomelandandculture. Schools In almost all of the schools, we were received warmly and enthusiastically by the teachers (seated in chairs), and students who sat for long hours on concrete floors, listening most attentively to our speeches and our answers to their seemingly unending flow of questions. These meetings typically lasted 8

- 17. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence from 1 ½ to 2 ½ hours, and at times ran into their dinner hour or free time. The youngsters were, for the most part, interested and well behaved. Where possible, we also spent one period with each of the sections of classes from grade 8 to grade 12. Over the years we must have spoken to thousands of students in large and small group meetings, and met with close to a hundred individualclasses. Almost everywhere we received gracious and considerate treatment by the Rectors and Principals. We were impressed with their flexibility and the many ways in which they were willing to disrupt their regular scheduling in order to accommodate this program and our timing needs. Many were also extraordinarily attentive to our personal needs, and went out of their way to make sure that we were comfortable, and that we had a chance to see the sights of the surrounding area. All of them felt that it was very important for the youngsters to receive such information, and most of them expressed a strong desire to see this program continue and expand in their schools. Memorable was the school in Dalhousie where the Principal had all the children line up along the driveway to bid us farewell. We asked them to join hands and sang “We shall overcome” ending, of course, with “Tibet shall be free someday.” Most of the children know this song, and the feelings were just as powerful as they were when Everett and I sat in a black church in Selma, Alabama during thestruggleforCivilRightsintheUnitedStates,almost50yearsago. Another moving response came from an Indian Principal at a CST school. (Schools for Tibetans set up by the Indian Government). He welcomed us warmly and told us how much he supported our work. Later, the vice principal came into one of our classes and asked to speak for a moment. He told the students how important this subject was and how much he supported their cause.Another moving time was at a Tibetan Homes Boarding School where, at first, the Principal and Rector received us with some caution. By the end of the week, however, we were invited to dinner at the home of the Rector on a Friday evening, our Sabbath, and shared our Sabbath customs of candle lightingandprayerswiththem. 9

- 18. ANEC week long training for Prof. and students from University of Alabama,USA May 2012. Group Photo with Participants (Leadership group) of ANEC Workshop in Ladakh, Sept 2008. 10

- 19. ANEC Workshop for TCV Sellaqui. Nov 2009. Group Photo of ANEC and Workshop Participants from Tibetan Transit School, Dharamsala. Nov 2012. 11

- 20. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Formatofthemonograph In the section called “Report” you will find a consolidation of the student's questions about Active Nonviolence, as well as their ideas about how to improve the lives of Tibetans in Tibet with regard to economic conditions, cultural preservation, religion, and educational opportunities.Also included are summaries of responses to questions pertaining to interaction with Chinese people – ordinary, military, and official, and in addition, their responses to what they would do if they were given the opportunity to attend Beijing University; would they go or not go. Pictures showing a “Chinese doing something to a Tibetan, and then of the Tibetan trying to get him to stop, are graphic and telling. Finally, I summarize their quite moving list of worries they have about Tibet, and what they think Tibet will be like if they return. In the Appendix you will find both a comprehensive list of the questions which the students asked us---for the most part unedited and in their own words---as well as their detailed responses to the questions we asked them to address. We include, also, their thinking about how to improve medical services, especially in the countryside, and special problems and solutions for farmers and nomads. Although lengthy, we thought that an extensive record of their thoughts, concerns, and proposed solutions would be useful in understanding what is on Tibetan students' minds in relation to the problems related to Tibetan exile, and to ideas they have for active nonviolent resistance. Obviously this is not a complete compendium, of students' ideas and responses, for such would fill many hundreds of pages, but it does provideasnapshot ofwhattheyarethinkingandfeeling. In addition to the above, there is one other area which I think needs special attention. The question about worries they have about Tibet elicited sobering and poignant responses. It is clear that the children are quite worried about what it is happening in Tibet, in terms of the social, political, cultural and environmental changes. But the concern is also terrifyingly 12

- 21. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence personal for those children whose families and relatives who are still in Tibet. Their worry is gnawing and heavy. They miss their families dreadfully, and worry about their safety. One student reported she had not seen her family in eight years, and worries and wonders if they are still alive. Another girl burst out crying during the workshop, and we later learned that her fatherhad beenarrestedand imprisonedwhen he spoke out ata festivalin Tibet a few years before.And then there was young Yanchen, a fourth grade girl who had not seen her family in Tibet for many years. She and a couple of her friends and I spent a lovely few hours together one afternoon. I asked her if she missed her family, and her response was swift and practiced. “I am very lucky to be here to get a good education.” She did admit that she worried about them. As I was leaving, she gave me a note addressed “My dear mother”. Mary, you are so good and very kind. Today you are going to America. I am very sad because you are my mother. Don't worry about me. I am very happy in my school. If you are going I am really cry. I love you my friendly in this world. I was born and my mother takes care of me, You are very beautiful. I love my mother. My mother is so good and brilliant. Her working is to cure the sick people. You area kind hearted woman and hard-working also. You love plants. Heartbreaking, poignant, and telling. Whether there is any space or place in the schools or “homes” where these children can express these worries is a question the Tibetan educational systems might explore. With sometimes fifty children in one house, the “Mother” could well be excused from being able to give each child a lot of personal support. Perhaps the school nurse, or guidancecounselor,couldbetappedtodothis. Summary ofOtherActivities In the paper I also include summaries of other activities in which the children 13

- 22. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence engaged,includingrole-playing,drawing,debatesandstorytelling. The final section contains their suggestions for, and assessment of, the workshops. Mostly they were excited and pleased, and wanted to learn more. They were very grateful that we had taken such an interest in their problems, and were all the more impressed because we had come so far, and we were so old!! FormatofourTeaching In the boarding schools we found it most effective to talk to a large group on the first night, followed by a visit to their individual classes the next day. We spent two full days in most of the schools, and thus were able to meet with most of the classes of the children in 8th to 12th grades. In some schools we also met with 6th and 7th graders. Despite having had instruction in English for only a couple of years, the younger children were often less inhibited about speaking up and expressing their feelings. A program geared toward middle schools students could prove very valuable. In some of the schools teachers were present at the meetings, and in other schools we had little or no contact with them. In each school we left it up to the Principal or Rector to arrangewhathe/shethoughtwas best. The large group meeting afforded us an opportunity to give an overview of active nonviolent resistance, and a few examples of the ways in which it had been used by other peoples in the world. We generally talked for about 45 minutes, then invited questions from the students. As many of the students were too shy to come to the microphone, most of the questions were written down and passed to us. Some of the bolder youngsters did come up to read their questions personally. We tried to answer every question, and the students sat patiently through our answers. At times they stayed through what would have been a free period, or into their dinner hours. It was astonishing to see how patiently they would sit, crossed legged on a cement floor. The visits to the individual classes gave us a chance to have more personal 14

- 23. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence contact with the children. Most of the classes had between 25-35 students. In these meetings we divided the class into small groups of 6-8 and asked them to consider various problems. Much of our teaching revolved around the followingtwoquestions: · What can Tibetans in Tibet do to help preserve their culture and language? · What can Tibetans in Tibet do to help increase Tibetan jobs and income? Among the almost limitless questions we could have asked them to consider, we chose these two for the following reasons. Our goal was to introduce them to Sharp's way of thinking about nonviolent struggle, and to have them practice applying some of the methods to their own situation. We focused primarily on preservation of culture and economic improvement in Tibet because it seems possible that some of these actions could be effective despite the repression. Political intervention is very dangerous at this time, as we saw with the uprising in 2008. It is our belief that if a wall is rock solid, rather than continuing to hit one's head against it, perhaps it is better to make anendrun andfocuswherethereisachanceofbeingsuccessful. In schools where there was no opportunity to go to individual classes, we would present some material to the whole group and then break them up into small groups – no more than 10 people – and give each group a specific assignment. They were to imagine that they were Tibetans living in Tibet under the Chinese, and they were to think of ways to begin to solve the above very real problems experienced by the people there. Whatever the focus of the question, we would subdivide the topic and assign one group to be nomads, another city dwellers, still another farmers, etc., in order to see how thisproblemcanbeaddressedindifferentsegmentsofthepopulation. Each group had 15-20 minutes to collect their ideas, and then one volunteer read the report to the whole class. If there was time, we discussed a few of their ideas in more depth. There was rarely time for this, however, as the 15

- 24. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence classes were, for the most part, only 40 minutes. Sometimes this was sufficient,butmostlywe feltitwouldhavebeenmoreproductiveforus to have had more time to follow up. In the few cases in which we had a double period, the discussion proved to be fuller and more satisfying. Had we more time with the students, after the initial exercise, we would have asked them to take one point from their list and develop it in fuller, concrete detail.Then we would have had them try to imagine the range of possible Chinese reactions to their actions. The next step would be to plan the range of their reactions to theChinesereactions,andso on. Smallgroup exercises,casestudies, activities Thegoalsoftheseexerciseswere: · To give the students the opportunity to begin to think strategically aboutactivenonviolentactions. · To give the children the experience of working cooperatively in smallgroups. · To assist the development of a realistic hope in the possibility of effective,successfulnonviolentactions. · To encourage the disposition to plan and participate in future nonviolentactionson behalfofcommunityaspirations. Case Studies In addition to the above material, we always included at least one case study of a successful nonviolence campaign in recent years.The very real stories of the resistance of the Norwegians to the Nazis, the Latvians to the Russians, the Czechs to the Soviet Union, the people of the Philippines to Marcos, the Serbian student group OTPOR to Milosevic, and now one could add Tunisia and Egypt as well as Palestinians, make fascinating telling and listening. Hearing about how other countries have successfully used nonviolence to gain freedom is inspiring, and illustrates concretely that this approach to politicalaswellassocialchangecanactuallybesuccessful. 16

- 25. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence Activities Role playing: Very popular in the United States, role playing was difficult for many of them because of their shyness. In the few cases in which they were able to get into it, they were very good, and showed their ability both to understand the situation in Tibet, and to depict new ways of resistance. Draw a picture: We asked the students to draw a picture of: 1) a Chinese doing something to a Tibetan, and 2) of the Tibetan doing something to get the Chinese to stop.As you will see, the pictures they drew were graphic and powerful. I show four in the body of the document, and several more in the appendix.Theyareworthseeing. Storytelling.: The assignment: You are in a village and someone in your familyissick.Thereisno goodmedicalcare.Whatcanyoudo? Debates: A favorite among the students, one group spoke to the need to use nonviolence,whileanotherrepresentedthecaseforusing violence. Additional Questions · IfyouareacceptedtoattendBeijingUniversity,would you go? · What are your feelings about Chinese Officials as well as ordinary Chinese? · Wouldyouwork fortheChinesegovernment? · Whatarethreeworriesyou haveaboutTibet? · Whatdo you imagineTibetwilllooklikeifyoureturn? · Whatcanstudentsdo foryourcountry? · How canthisinformationgetintoTibet? For all of these topics, there is first a summary of the student's responses according to categories, and a full compendium of their responses in the Appendix. TroubleintheHinterlandsofChina: Often, in response to their despair over the situation in Tibet, we would cite the demise of the Soviet Union, a most ferocious tiger indeed, noting that no- 17

- 26. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence one could have imagined that it would crumble the way it did. Those countries under the Soviet domination which were ready to push for their independence, took advantage of the turmoil and vulnerability in the Soviet Union, and got their freedom. Those who were not ready, did not, and are still under Russia's heavy boot. We noted that NO dictatorship has lasted forever, and urged them to get as prepared as possible - strengthening their culture, improving their education and economic situation - so that when Chinastartstorumble,theywillbereadytotakeadvantageofit'sweakness. Although at this point China seems invulnerable, there is a great deal of anger, unrest, and desperation, especially among the peasants in the countryside, who have been forced to sell their land at a very low rate to local officials, who then sell it to developers for a huge sum, leaving the peasants no way to make a living. There is also frustration and despair among the workers, who have been laid off as state run factories closed, and have not been able to find work. It is our understanding that there are tens of thousands of demonstrations annually throughout China, many serious enough to involve the military. Let us not forget that it was peasants who were the foot soldiers of the Communist Revolution. The current rulers of Chinaknow this,andarequiteworriedthemselves. On top of all this, there is rampant corruption on the part of officials. Another major concern is that it is becoming harder for the state to create sufficient work opportunities for its burgeoning population and maintain growth without crippling the environment.Along with industrialization has come pollution of the air and rivers, and in the near future, water supply is expectedtobecomecritical. In addition to the dissatisfaction in the countryside, a generation of newly educated, curious, and ambitious young people has grown up with the internet. Like others around the globe, the young people use the internet as a window into what is happening in the world, and as a place to learn about and engage in exchange of information. Some of this information the government deems dangerous to the “stability” of China, and tries to block 18

- 27. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence access to these dangerous sites. But the young people seem to find ways around these barriers. Consequently, huge symbolic and actual capital is spenton policingtheInternetandsuppressing dissent. Even the Chinese Government has acknowledged these as major problems. How the leadership of China can continue to manage these strains, constantly off setting economic expansion with political conservatism, is anybody's guess. How these areas of weakness of the Chinese can be exploited by the Tibetans bears careful analysis and planning. How to make common cause with dispossessed Chinese farmers and workers, as well as with students and others wanting Democracy, and with other minority groups seeking independence, such as the Uighurs, is a question worth exploring. Most of the students did not know about these problems inside China proper, andfound theinformationheartening. NotableQuotations fromStudents The following quotations of the students are so striking that it seemed worthwhile calling special attention to them. Taken together, they reflect therangeoffeelingsandthoughtsof mostof thestudents. · InthistimeIstayinIndia,butmyheartisstillinTibet. · When willTibetbesunshine?Whenwillwe gatherinourland? · I will give my life for freedom, but I cannot give my freedom to the redChinese. · Ifthereisnotnonviolence,thenwhatwillhappenintheworld? · Our Tibetan spirit is one of our strongest strengths. If we continue to strengthen our high morals and Tibetan identity, nothing can suppress thehumanspirit. · Tibetanisouridentity.Weshouldgettoknow it. · As weallknow,nonviolenceisthepillarofhappiness. · I amapeacelover,butI don'thavemuchideahow tocreatepeace. 19

- 28. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence · Once we start practicing nonviolence, will we automatically becomenonviolent?” · Is violenceinherenttohumans? · Whatistheimaginarylinebetweenviolenceandnonviolence? · Iamguy frustratedonthepathtononviolence. · By not using violence against the Chinese, we have been inflicting violenceon ourselves. · Freedom is not an easy thing. We have to use our thinks and knowledge. · The young Tibetan generation must understand that they are the heirsof Tibet.Withoutapeople,whereisanation? · We are ready to do almost everything, for Tibet, but we don't know whattodo. · How canwewait100 yearswhen peopleinTibetareindespair? · Holdtightlytoyourcultureandneverletthemwash your brain. · My recognition will be from my culture, but degradation of my culturebytheChineseGovernmentismyfirstworry. · I will study damn hard and be a good woman in this world. Once I become a great woman, I will show the world the two faces of the Chinese. · When I start to do anything for my freedom, I will not go through violence. Iwillgo throughnon-violence. · Idon'twanttoknow theircultureandreligion.Theyareourenemy. · I'm not going to Chinese school because I don't like Chinese and I can'teatChinesefood”. · What are we teaching our children? Are we teaching them to hate? (teacher) Summary ofStudent Questions In the early years, 1995-8, the children were rather timid about expressing their disappointment in the outcome of the nonviolent actions used so far in 20

- 29. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence the freedom struggle. As the years went on, they expressed frustration and skepticism about the efficacy of nonviolence as a way to gain freedom or autonomy for Tibet increased substantially, and they became bolder about advocating the use of violence with nonviolence. One boy reflected the opinionsofmanyashearguedopenlythat“itistimetogiveviolencea try.” The thought that it might take much longer was anguishing to them. They seem convinced that Tibetan culture, religion, and language, as well as the people and the ecosystem, are on the very brink of disappearing. They want to know “how long it will take” with nonviolence, and they express fear that if they rely on it for their freedom, there will be nothing left of Tibet by the time they return. They see violence as giving faster, more definitive results. As one student said, “How can we wait 100 years when people inTibet are in despair?” The frustration of the students is evident in the question raised in every group we spoke to: “ The Tibetans have been using nonviolence for 40+, now 50+ years, and it does not seem to be working.” Some asked “why” this was so, and wondered if there were other ways we could suggest. Many of the questions had a plaintive quality, a tone which suggested that they desperately want to believe in the power of nonviolence, but don't really see how it can work for them. They stated that they felt “frustrated”,“discouraged”,“disheartened”. The students asked many questions about the concept of nonviolence, and what we mean by “active nonviolent struggle”. Does it mean “truth”? “Can you play tricks”? They asked us to define “satyagraha”, and they wondered if there are differences between the Western and Buddhist points of view about nonviolence. “Is nonviolence is part of the Buddhist religion?” they ask,and“whydosomeWesternersbelieveinit?” What is the role of anger in nonviolence, and how can you overcome and control it?” they asked. They also wondered how to overcome depression, and fear. “Why,” they asked, “do we have more negative emotions within 21

- 30. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence our mind than positive ones?” They ask if they can “adopt the theory of nonviolence in any other sphere at our lives except the struggle and protest politically”.And finally, and with hope they asked, “Once we start practicing nonviolence,willweautomaticallybecomenonviolent?” Some of the questions about nonviolence were philosophical. “Is violence inherent to humans,” they wondered? “Everyone wants and needs peace on earth, so why do the people make those weapons of violence?” asked one youngster. Another said simply, “If there is not nonviolence, then what will happentotheworld?” The children struggled mightily with the questions of use of violence vs, nonviolence, and wondered if they could use both.“What is the imaginary line between violence and nonviolence? and “why do some countries not go through nonviolence?” “If nonviolence is best, then why do the developed countries, with the most educated people, use violence?” Indeed, they note, “Why do scientists continue to make atom bombs, guns, and nuclear bombs?” They accuse the developed countries of “double speak,” “hypocrisy.” “They (other countries) speak of nonviolence, and train militia.” The students wanted to know in what country nonviolence began; why some followitandothersdon't;whetheritis ashort or longtermstruggle;andifwe think it will really work to get them their freedom? If so, what are the best methods to use? They question whether it will work, however, when “the opponentdoes nothavea littlebitofhumanity.” They wondered how nonviolence is related to the “middle path”. (Dalai Lamas offer of true Tibetan autonomy but under the mantle of China.) They note that “many big nations accept that Tibet is part of China.” Given this, theysay despairingly,“howcanweeversucceed?” As the years passed, a striking number of them, feeling frustrated about the ability of nonviolent actions to deter the Chinese, openly advocated “giving 22

- 31. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence violence a try.” One student, an eighth grader recently come from Tibet, argued that “by not using violence against the Chinese, we have been inflicting violence on ourselves.” Others, more timid about suggesting the use of violence, asked somewhat obliquely, “by violence we cannot take our countryback,so whatshallwedo?” Many of them pointed out that despite struggling nonviolently for the last forty-fifty years, things keep getting worse in Tibet. One girl wondered why nonviolence was useful, since the Chinese beat and injured them. In addition, she said, “the Chinese are rapidly using up all the resources in Tibet, and by the time we get our country back, I foresee Tibet totally barren, with no resources, and a dumping place for nuclear waste.” So, she concludes,“itistimetouse violence.” Students seem to have a good grasp of history, and frequently used historical examples to illustrate the ways that violence has been used effectively in the past by other countries. Most countries, they argue, have gained their freedomthroughviolence.Whyisnonviolencebetter? Not surprisingly, they were quite well informed about India's freedom struggle and Gandhi's nonviolent campaigns.They see the Chinese as a more formidable foe than the British were, and assert that “time and men have changed.” They also pointed out that it took the Indians 200 years to gain their freedom, and that they used both violence and nonviolence in their struggle. Some advocated “revolutionary acts” along with the nonviolent movement. “Everyone wants and needs peace on the earth, so why do the people make thoseweapons ofviolence?”plaintivelycriedonestudent. To us, (as Jews), some of the more poignant and pointed questions about nonviolence concerned the Israelis. While marveling at the Jews' ability to maintain their traditions and culture for over 2000 years, they also noted: “The Jews were in diaspora for 2000 years without violence. Now with 23

- 32. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence plenty of violence they have a country. On the other hand, one young man wrote pointedly, “The Israelis are oppressing the Palestinians. If Israelis, people who have themselves undergone brutalities and injustice first hand from others can do this, then I wonder what hope there is for compassion and nonviolence.” “Why is China doing this to Tibet?” some asked in innocent bewilderment. “Why are they beating and torturing our people? Why are there so many jails? Why did they take Tibetan land even after having their own?”Another asked, “Why, even though the Chinese leaders are educated, don't they believe in nonviolence?” “If China changes to a democratic form of government, might there be a chance for Tibet to get freedom?” one girl asked,hopefully. Many see the only hope for Tibet as rescue by a powerful outside force, specifically the Western powers or the United Nations. They wonder why other countries have not come to their aid, why they don't raise their voices, take action against China as they did against Germany and Iraq? A large number of students expressed disappointment that the United Nations has not done more to help the Tibetans. One youngster accused the UNO of appeasement. “Are they afraid of the Chinese government?” he wondered. Hunger strikes, peace marches, none of these nonviolent actions seem to have had any effect on the United Nations, others complained. Another bright young student said, “The ecological damage done by the Chinese in Tibetaffectstheworld's environment,so why doesno oneintervene?” It was clear to us that the students had been deeply touched and mobilized by the hunger strike and self-immolation ofThupten Ngodup. “We have not met since the shocking rash of, to date, of 100 Self Immolations in Tibet this past year.” These actions seem to have raised their expectations, and many expressed grave disappointment that there has been no response from the United Nations. Several wondered whether or not we thought the hunger strikeorself-immolationswere nonviolentacts. 24

- 33. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence They were fascinated to hear that we had gone to Tibet, and asked us many questions about it. They wondered why we had gone, how we felt when we were there, and whether Tibet is really different from other countries. They also wanted to know how we were treated by the Chinese, and if we had any problems. They asked if we had visited any prisons, whether there was destruction everywhere, and whether we could speak about nonviolence during our visit. They were also quite concerned about the people. They wondered if the Tibetans get medical treatment when they are sick, and worried about how the children were going to learn. Finally, they were curious to know if there are differences between Tibetans in Tibet and Tibetansinexile. The older students posed some sophisticated questions. They wondered if the Western view of nonviolence includes “refraining from negative thought and action,” and if it includes “all sentient beings or just humans?”They also wondered about “the relationship between democracy and the nonviolent strugglewithregardtotheexilegovernment?” They questioned how the people inTibet could organize given the repression there, and they asked how useful nonviolent resistance would be against the Chinese, since “they have the power and we have none.” Another student bluntly stated: “Fact. We can't achieve independence. There are six million Tibetans and 7.5 million Chinese in Tibet. Even if we get independence, we can't kick out the people.” Not everyone was so pessimistic, however. Others spoke of the “need for non-cooperation actions in Tibet, and sharing of information between Tibet and the exile community.” One teacher raised a sobering and important question about whatTibetan teachers and parents are teaching their children about the Chinese. “We are teaching them to hate and Whatdowethinkaboutthis?” SUMMARYOFSTRATEGIES One of the lynchpins of our teaching was to break the students into small 25

- 34. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence groups where they would focus on real problems in Tibet. These “problems” were discussed among themselves, and the students were asked to come up with strategies which could make life better for the Tibetans in Tibet.Hereisasummaryoftheirideas. ExilecommunityandTibet Some of the participants rightly pointed out that it is the Tibetans living in Tibet who need to have, and put into practice, this information. As one participant noted, “since there is no likelihood of anyone carrying out a workshop like this in Tibet itself, how to arouse this knowledge and awarenessinTibetanswithinTibet”? They wonder what they in exile can do to help, and if Tibetans in exile should return to Tibet to contribute their knowledge to other Tibetans there. One student suggested that the exile government should offer courses in Chinese, so returning Tibetans would be able make their way in Tibet while helping the people there “lead better lives”. They thought that the education they received in exile would give them an opportunity to return to Tibet with new tools to help. “The educated people from exile will bring in ideas from the rest of the world, and may be able to negotiate with the Chinese.” They acknowledged the danger of doing this, but bravely said, “If wegetcaughtwedon'tcare,forwewantTibettobefree.” How to Conduct Protestand ResistanceinsideTibet Inside Tibet, they first need to look for like-minded people, people they can trust, and “people who are willing to die for the motherland”. They must find ways to guard against “leakage of secrets,” and “talk to those who are really known to us.” Next is the problem of finding funds. They suggested approaching prosperous traders and businessmen for support. In order to spread the ideas, they could act as traders, businessmen and move about the land. They also suggested using beggars, shoe polishers, petty traders, as intermediaries to share information and to communicate with each other. Lamas should be involved because their involvement will add legitimacy to 26

- 35. ANEC special Training Session for General Manager and Officers of PN bank, Jun 2009. ANEC Day Program at Tibetan Transit School with Activist Tenzin Tsundue, Feb 2009. 27

- 36. ANEC Workshop for the Leadership group from Majnu Ka Tilla, Delhi. Oct 2009 ANEC Workshop for Sambhota School,Dickeyling. Oct 2009 28

- 37. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence the cause and the “people respect them.” Finally, one group suggested that if Tibetans got an opportunity to work for the Chinese Government, and could do so without losing their Tibetan identity, then “they could spy for the sake oftheTibetanGovernment,andthiswould begood.” Question: What can Tibetans in Tibet do to help increase Tibetan jobs and incomeinTibet? Numerous reports have shown that the Tibetans, on the whole, are much less well off than the recent Chinese immigrants. There is a loop which goes like this. The best jobs go to the Chinese, which means that they can better afford to send their children to school for secondary and higher education. This gives Chinese children a better chance of finding lucrative employment, and of leading comfortable and economically secure lives. Thus, the Tibetans need to develop strategies to strengthen their economic prospects, while at the same time, weakening those of the Chinese. Put another way, the question is, “How can Tibetans organize to raise costs and reduce profits of ChineseinTibet,andtherebyimprovetheirown economicconditions”? Economic Non-cooperation: boycotts To this end, boycotts, both against selling to or buying from Chinese, can be very helpful. The goal of the boycotts, the students said, is to “make the Chinese less powerful by developing our own businesses, and boycotting Chinese goods. This will naturally make Chinese business weak, at the same time it will make Tibetan economy stronger.” This is true for all segments of society, including workers, farmers, nomads, businessmen large and small, professionals, academics, students. “A boycott goes both ways,” said one boy astutely. “It prevents Chinese from getting business and it supports Tibetans.” Another student put it this way. “We see that most of Tibetans in Tibet, as well as in exile, use Chinese goods. They think that everything which is produced by Chinese is better. We are told that boycott and non- cooperation movement is one of nonviolence method to struggle. If that is 29

- 38. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence so, thenweshouldboycottChinesegoods.” With regard to farmers and nomads organizing a boycott, the students suggested the following steps: 1) Distribute a secret pamphlet within the Tibetan community telling about the plans. 2) Arrange the different places where the Tibetan wheat and other goods are available. 3) Sell the wheat and other goods in the market for lower rate for theTibetans than for the Chinese. 4) Educate people about agriculture, animal husbandry, normal business especially in rural areas. 5) Form associations and plan boycott of wheat fromChinese. Others suggested that the food they grow should not be sold to the Chinese, but rather used for their own benefit, within the Tibetan community. In cases where they had to sell to the Chinese, it should be for a higher price. They urged Tibetan farmers not to let Chinese lease their land, and to make use of open, unused land themselves. With an eye to improving their production, they urged the farmers to adopt new methods, and to have quality control sessions to insure good quality of the wheat. The goal of all of this is to strengthen Tibetan farmers economically, and to lessen business and income fortheChinese. These same principles hold true in relation to businesses. In the course of boycotting Chinese businesses, both in terms of not buying from, nor selling to Chinese, the Tibetans, de-facto, will be strengthening their own businesses, bettering themselves economically, while depriving Chinese of income. “Buy only from Tibetan shopkeepers clothes and edibles which are produced by Tibetans”, they counseled. “ Do not go to Chinese restaurants, hotels, or banks. Set up cottage industries and factories to make and export their unique arts and crafts, as well as to produce shoes, clothes, caps, aprons on a large scale to meet the needs of other Tibetans.” “Tibetans should employ only Tibetans, and help other Tibetans who are in need,” they say. The students seemed to understand the need to keep up to date with new methodsandideas,andtheyurgeutilizationofnewtechnologies. 30

- 39. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence On the flip side, some urge Tibetans not to work for Chinese, either in the Government or in businesses or organizations, not to hire Chinese workers, not to buy from Chinese shopkeepers, not to get help from Chinese which wouldbenefitthemandnottheTibetans.. What canTibetans inTibet do to help preserve theirCulture, Language, and Religion? Another area we explored with the students was the preservation of culture, language, and religion. As mentioned before, the children are desperately afraid of losing their rich culture and deep religious life, qualities which, for them, are the essence of what makes Tibetans unique. They also fear losing their language. They offered a number of ways to stem theirloss. Language With regard to preservation of language, they urge that Tibetans speak to each other in pure Tibetan as much as they can. “Do not mix in Chinese”, they admonish. In school the teachers should make every effort to teach in Tibetan, not Chinese. But where this is not possible, “the teachers should teach Tibetan to the children secretly. She could take them to a remote place for a picnic, or teach them at night.” Parents should also speak Tibetan to their children, and read stories to them at night, like the Dalai Lama's book, My Land and My People. Some stressed the importance of children learning Tibetan language and culture from elders. “Tibetan history and other stories should be shared at home.” Make underground schools, they advise, produce a Tibetan newspaper, speak Tibetan in all hotels, restaurants, give Tibetan names to new inventions, make Tibetan language compulsory for all University students. And finally, “Spread the news to the world about the killingofourlanguagebytheChinese.” Culture Proving themselves to be fully into the “wired” age, the students offered 31

- 40. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence several suggestions about preserving Tibetans culture by making use of the new technology. They suggested making a “cyber-link among Tibetans around the world.” The internet should be used as a way to share Tibetan made films, literature and songs with those in Tibet. “Films and shows related to Tibetan history should be made and showed over and over to Tibetan youth, so they know the truth.” Conduct an essay contest which is about“maintainingour faithandaestheticmanners.” Some suggested that they should buy and wear traditional Tibetan dress. Another group advised making fashionable traditional clothing; and yet another suggested that they wear only regional clothing and burn all their Chinese clothes. Someone else suggested opening more tailor shops to make Tibetan clothing cheaply. “There should be cultural days when everyone wears their traditional clothing, dances Tibetan steps. Beyond that, more cultural institutions should be established where cultural shows are performed. Youngsters should learn Tibetan dance and songs from each other, and from Tibetan elders. Traditional Tibetan instruments should be obtained, and children should be taught to play them. New Tibetan songs should becomposed.Tibetanchildrenshould playTibetangames. And still more ideas: all Tibetan holidays should be celebrated without failure; Tibetan architecture should be revived. In Tibet, people should remain in their villages instead of moving into cities, because it is easier to maintaintheirown wayoflifethere. Religion The Tibetan Buddhist religion clearly plays a major role in the lives of these students. They value it greatly, and revere the Dalai Lama and his teachings. “The things we know about our religion should be kept in our mind throughout our life,” they say. And the teachings of the Dalai Lama, should be spread all over the world. Contact with Monks is important, because “ all Tibetans need prayer in their home, and the people can discuss with the monks how tomaintaintheirculture.” 32

- 41. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence The youngsters shared their ideas about to how to preserve their religion. “Look for young children who want to become a Monk, especially those from poor families, and who have no parents, and send them to Monasteries,” they advise. At night the people should try to get private teachings in their homes. Elderly Geshes from exile might return and teach about religion and culture. Monasteries should be built in Tibet. In order to do this, “a small group from exile should go to Tibet, establish relations with the Chinese there, and request permission to build a Monastery. If they say yes, we will beg donations from the Tibetan people and people from other countries. It should be built in a village where there is no monastery, and a Monk fromtherecanteachthevillagersaboutBuddhism.” ConstructiveProgram Another concept we introduced was that which Gandhi called “constructive program.” He developed this idea when, at the beginning of his campaign to free the Indians from British rule he noticed that many, many, of the peasants and workers in India were so poor, sick, malnourished, and uneducated, that they were not in condition to participatein a freedom struggle. Consequently, he set up projects in the villages aimed at improving the above problems.The development of latrines was one of his first campaigns; creating cottage industries, such as spinning, weaving and sewing their own clothes, was another. He believed that only when people were adequately fed, housed, healthy and self-sufficient, could they fully participate in nonviolent campaigns to gain their independence. This situation holds true for many in Tibet,especiallythefarmersandnomads. Farmersand Nomads: Problemsand Solutions During the workshops we sometimes ask the students to focus on the situation, problems and needs of one particular segment of society. Here they focus on farmers and nomads. What follows is a summary of the problems they perceive, followed by some ideas about how to improve the situation of 33

- 42. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence the farmers and nomads. I quote much of this to show the level of detail the studentswereabletogenerateinabouttwentyminutes. Problems: 1) Nomads have been forcibly resettled and their former grazing lands have been wired off, and this without adequate compensation, 2) Heavy crop taxes,3)Lowpricesfromgovernmentforfood, 4)Highfeesforeducation. Needs and Concerns 1)Information about new methods of agriculture, and ways of increasing yields; 2) Health and hygiene information and practice; 3) Guidance about ways to maintain their culture; 4) ways to boycott Chinese goods and improvetheireconomicsituation. The students begin by noting that “Tibet is a fertile land”, and farmers can produce “many crops in large scale to sell.” They warn that they should not sell to Chinese, however, or if they must, they should ask a higher price.They also should not lease land to Chinese. They caution that farmers should “avoid buying fertilizers, pesticides and manure from the Chinese”, and state that Tibetans should buy food from the Tibetan farmers in order to support them. At the same time, the Tibetan's wheat should be sold only within the Tibetan community. Nomads should avoid selling domestic animals to the Chinese. They also advise nomads to “minimize the use of Chinese technologies,suchastrucksandtransportation.” Farmers, they say, should learn about and adopt new methods of agriculture, including crop rotation, irrigation, organic farming, use of high yielding seeds, etc., in order to increase the quality of their produce. They should send some of their young people to advanced countries to specialize in wheat production. The students also suggested organizing workshops, showing videosandslides,tointroducefarmerstonewmethods,ideas,equipment. One group of students advised a return to water mills, the traditional way of grinding grain. “Our main objective of this is to stop using Chinese goods 34

- 43. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence and machines so we will depend less on the Chinese.” They go into some detail about how to do this, and the advantages of doing so. “At present, the farmers are dependent upon electric mills which are imported from China. These are expensive, and all the money goes to Chinese merchants.” In order to construct a water mill, they advise raising money in the Tibetan community and spreading the word through pamphlets. Tibetans will be given a discount rate, and the operating costs will be lower both for the farmer running the water mill, and for the farmers bringing their grain. The millwillgiveemploymenttoTibetans,andis“eco-friendly.” Culture In thinking about how to preserve Tibetan culture in the countryside, the students advise starting schools which “give special emphasis to the importance of Tibetan language, culture and traditions.” “Compose songs, make farm organizations to preserve traditions like performing folk dances on important occasions.” “Remind farmers of important dates like birthday of His Holiness, Tibetan uprising day.” Hold meetings while working in the fields where they can talk about the importance of wearing Tibetan clothes, and speaking the Tibetan language. Construct a playground and encourage playingoftraditionalTibetangames. Healthand hygiene The students noted many problems relating to health and hygiene in the countryside, including: 1) A paucity of hospitals in rural areas; 2) Poor facilities; 3) High charges for treatments and medicine; 4) Scarcity of doctors; 5) Lack of professionalism, and 6) The need and fear of female patients to go to Chinese doctors “who impose forced unconscious sterilization.” Some of the solutions they proposed were as follows. “Open hospitals in the villages; establish small medical centers owned by Tibetans; boycott medicine made by the Chinese; produce and make available an adequate 35

- 44. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence supply of Tibetan medicine which is cheaper compared to Chinese pills, and has no side effects; establish new pharmacies; give education in Tibetan medicine to our youngsters.” In an interesting twist, they say the Central TibetanAuthority in India should train paramedics to go into the countryside and service the farmers and nomads. And finally, a balanced diet should be encouraged. “There is a need for hygienic education among the villagers, and talks should be given monthly. Water filters should be provided for clean water; open toilets and traditional toilet systems should be discouraged; proper latrines, withproperdrainagesystemsshouldbeinstalled”. Forcedrelocation “The Chinese are forcing the Nomads to fence in their grazing land in ways which have never existed before. This is causing them to quarrel with each other as well as costing them money. Taxes on milk, butter, meat are high; limits on land and livestock have been imposed. They need training in land and water management, and could profit from knowledge of how to take care of their animals. Jamming of VOAand RFAmeans that they are cut off from information about what is happening in the world. Now the Chinese government is forcing the nomads to live in “settlements” where there is no work, nowaytoearnaliving.” Pooreducationalopportunities Lack of, or poor, education move is a major problem. The teachers are not qualified,the schools are not adequate,and the fees afterelementarylevelare toohigh.Lackofeducationleadstomenialjobs andtolowearnings. To correct this, nomadic parents should be encouraged to send their children to school. Some of the Tibetan students in India bravely, if naively, say that after they finish their own education, they will go to Tibet and teach nomadic childrenforfree,eveniftheygetarrestedandputinprison. 36

- 45. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence ProblemsinTowns and Cities Problems: Overview 1) Overwhelming Chinese presence, 2) Education: almost free in primary school, nominal fees in middle years, high fees in higher studies. Many school dropouts, 3) Cultural survival, 4) Discos, bars and brothels and consequent corruption of young people, 5) Religious persecution, indiscriminate arrests, political reeducation, expulsion, imprisonment, 6) Loss of jobs because of spiritual affiliation toward Dalai Lama, 7) Jamming ofVoice ofAmerica and Radio FreeAsia, 8) Forced to celebrate Chinesefestivals/ceremonies, 9)Indiscriminatesearchingorchecking. Corruption ofyoung people The students in India have heard about the proliferating bars and houses of ill repute inTibet.They are very concerned about this growing corruption of the youth, and suggested a number of ways to deal with it, all, perhaps, a bit naïve, but well-intentioned. First, they say, “there should be a ban on bars”. They propose finding those people who drink too much, and telling them”not to do this”. They suggest reminding the wayward youth about the things China has done to Tibet, and advising them that they are falling into theChinesetrapby livingalifeofdissipationandidleness. Another group offered a clever “juijitsu” scheme for maintaining Tibetan language. They wrote,“There should be a night club, and inside there is an underground room. Some persons have to dance and show they are enjoying the music. The children and teacher should be in the underground room learning Tibetan. If the Chinese come to know about the club, then other people there have to show that it is a disco playing English or Chinese music”. What Can Students do fortheirCountry? The students say they are “ready to do almost everything, forTibet”, but they 37

- 46. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence don't know what to do. The teachers tell us we should study, and then we can get our country back, they say, but we don't understand how. “How will the education bring freedom?” they wonder. The students are told that they are very lucky because they can get a good education in India, while their peers inTibet are not always able to do this.And for the many children sent by their parents on the perilous journey across high mountain passes from Tibet to India, this opportunity to get an education means long term or perhaps permanentseparationfromtheirfamilies. Of course the primary job for these students is their own education!!There is no question about that. But the concerns about the Motherland weigh heavily upon them, as is made clear in their questions. How to channel this energy and respond to the student's clear desire to help in the freedom struggle is, we suggest, worth exploring. Far from over burdening them, as one educator suggested, we believe that active participation in the freedom struggle, however small, will speak to their need to help, to be useful, and bring the youngsters hope, and counterdepression by providinga sense of purpose and empowerment. It is important to note, however, that while some of the children seemed at a loss as to what they, personally, could do, others were very creative in their ideas, as you will see below. Following this list are three very well thought- out strategies which show the kind of strategic and original thinking of which thestudentsarecapable. Nonviolentactions 1.“EachTibetanwillwritelettertoUN reportinghumanrightsviolations.” 2.“MaintaindemonstrationseverywheretoirritateChinese.” 3. “Create a conversation chain letter. Pass on learning from teachers to friendsandfamily,andtheythenpass ontoothers.” 4. “Make campaigns secretly regarding Tibet issue, and make aware to the common people by distributing newspaper journals etc. which are published 38

- 47. Frustrated on the path of nonviolence on FreeTibetaffairs.” 5.” From different states of Tibet, once a month there should be a discussion among some well-educated on the topic about Tibet so that we all can share andknow betteraboutTibet.” 6. “Information network through writing pen pal letters at global scale, therebymobilizinginternationalsupport.” 7. “China's constitution has already framed the right to preserve minority culture. So we must endeavor peacefully to plead the China's government to maketheminorityculturebeapplicableinour dailylifepractice.” 8. “Organize NGO secret agencies in Tibet, which can distribute pamphlets tourgethepeopletopreserveculture,asourunitydependsonit.” 9. “Send an individual to numbers of houses to educate the parents about the importance of our culture, language, and especially the importance of sovereignty.” 10. “The various people traveling back into Tibet should take cassettes and CD's on Tibetan religion and culture to distribute in Tibet, secretly, by Tibetans.” 11. “Develop secret communications with various administrators in Tibet related to education and culture to make our activities more supportive and effective.” 12. “In Tibet we should migrate from place to place. By this we can pass informativeinformationtoothers.” 13. “ Through newspapers and journals we can spread what is happening in Tibet,andtalkabouthow tohandletheproblem.” 14. "All Tibetans have to be in unity on our campaign to preserve our tradition and culture, like the Norway teachers had done for their country andpeople.” 15. “Wehavetoknow how theChinesetorturedus andtellotherpeople.” 16. “We must eliminate the relationship between Tibetan and Chinese on economyso naturallytheybecomeweakthenwecangetourfreedom.” 17. “Increasing number of Chinese is a threat to our culture, and to stop that 39