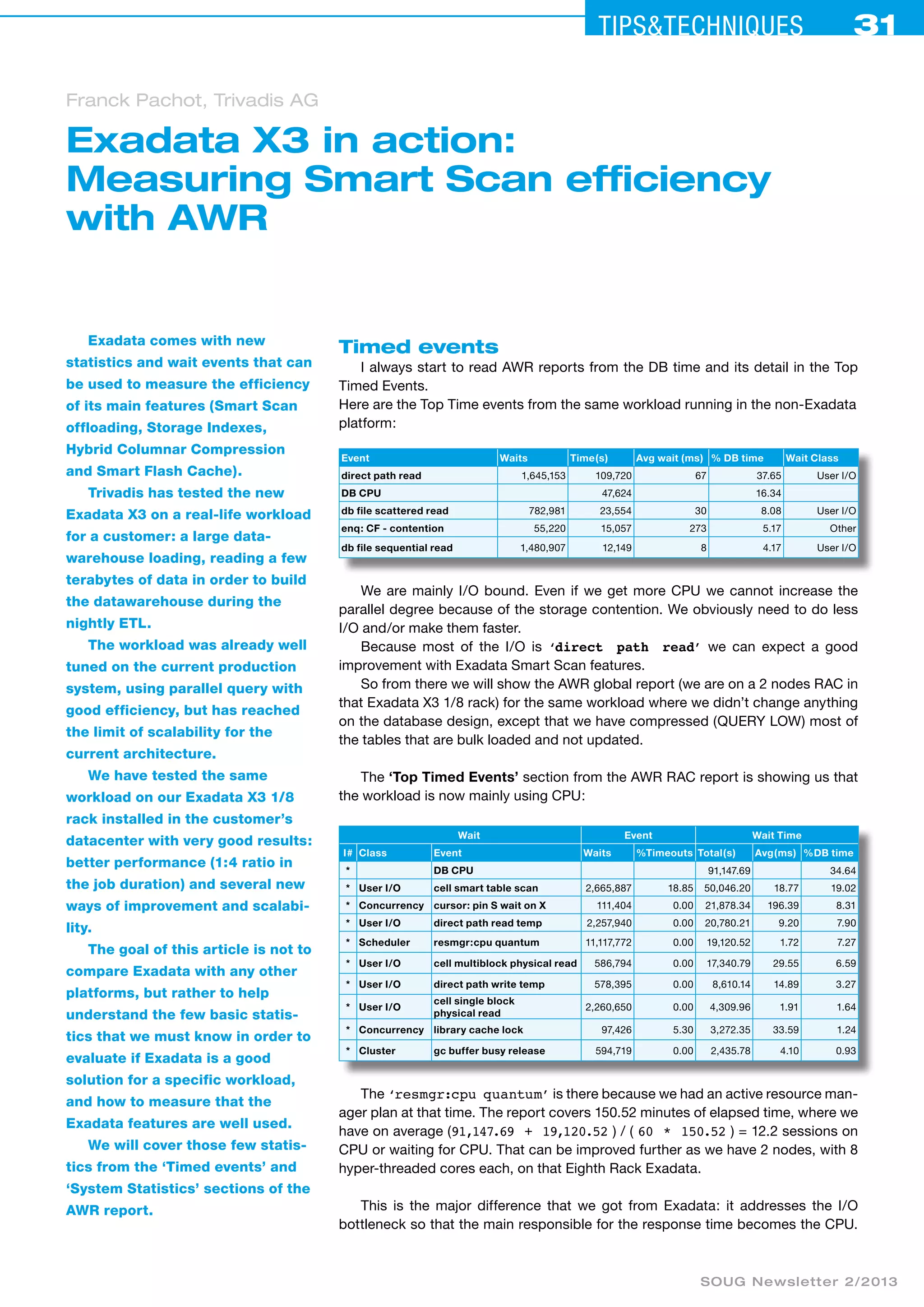

The document discusses the efficiency of Exadata X3's smart scan functionality by measuring its performance on a large data warehouse ETL workload. It highlights significant improvements in processing time and resource management, where the I/O bottleneck is reduced, allowing for better CPU utilization. It also explains various statistics related to timed events and system performance that demonstrate how Exadata features enhance data processing capabilities.