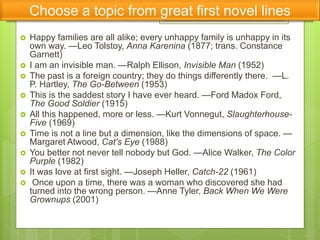

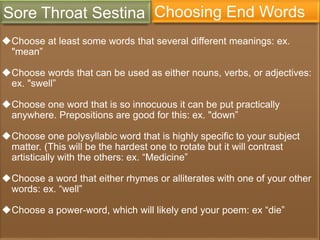

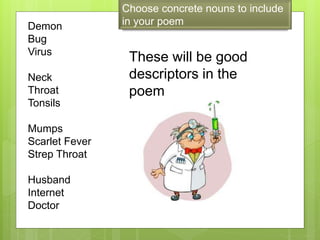

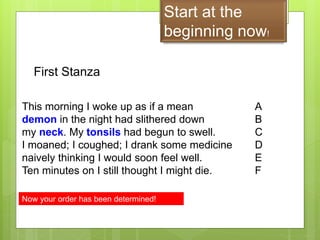

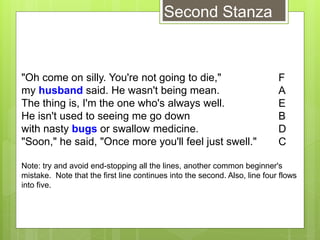

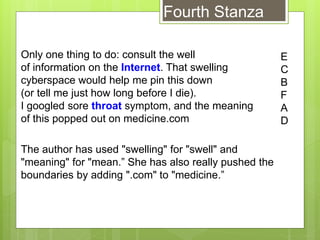

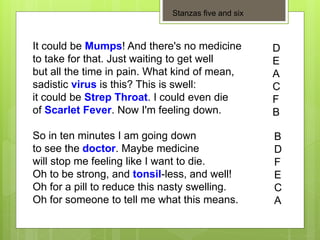

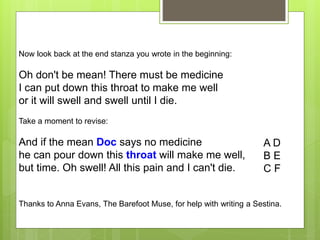

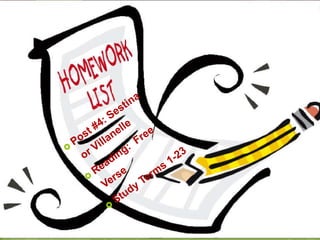

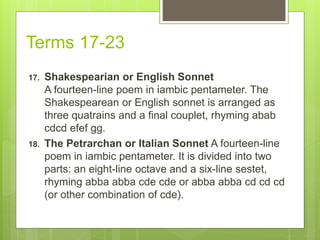

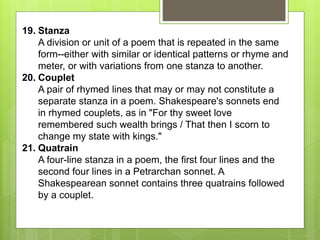

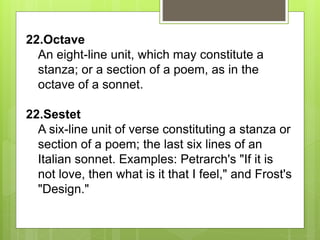

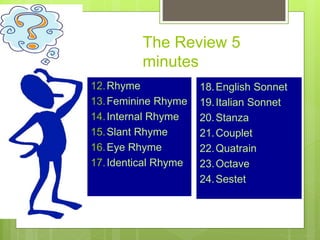

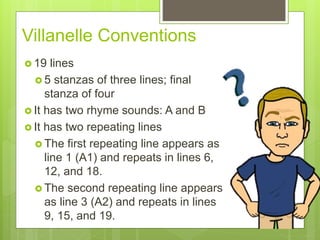

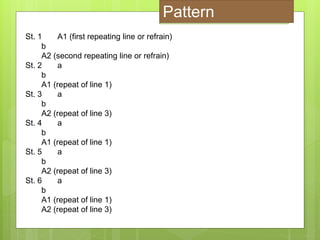

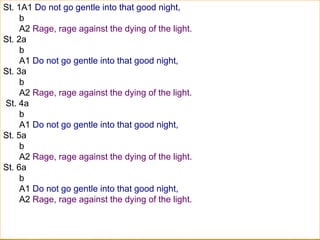

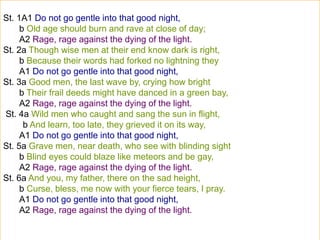

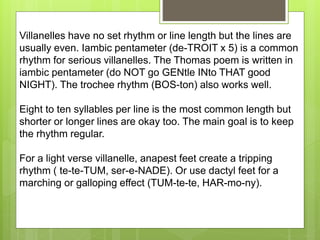

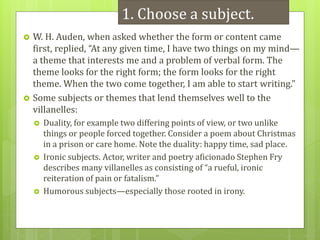

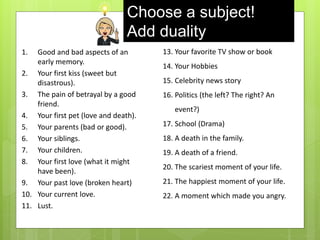

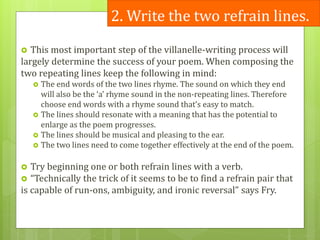

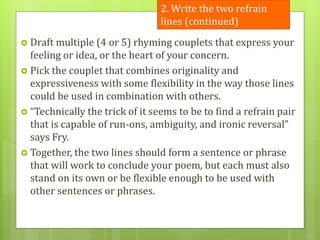

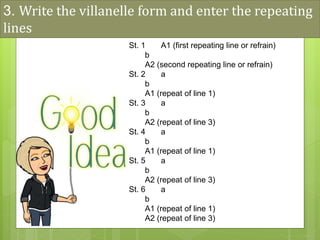

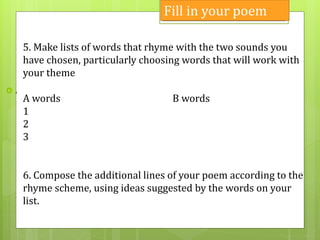

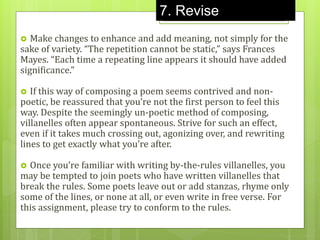

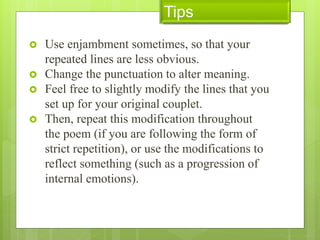

The document provides an agenda for an English class that includes discussing sonnets and learning about poetic forms like the sestina and villanelle. It defines various poetic terms and conventions used in sonnets. The class will also participate in a guided writing exercise on a sestina or villanelle where they choose a topic, write repeating lines, and fill in the form according to the rhyme scheme.

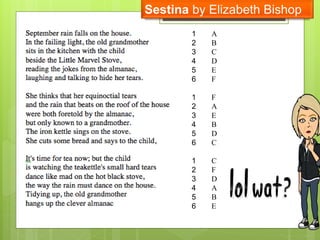

![Sestina

Conventions

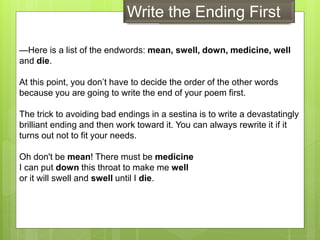

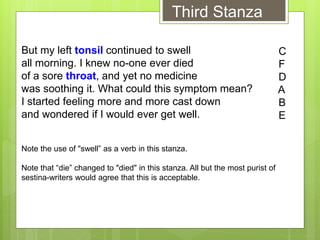

The sestina makes no demands on the poet in terms of meter or rhyme or

foot. Its requirements border on the mathematical and its prescriptions are

mainly syntactical.

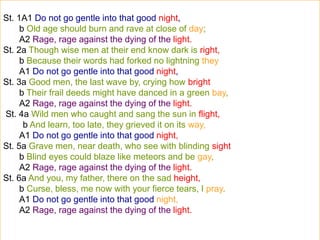

In Questions of Possibility: Contemporary Poetry and Poetic Form, David Caplan

explains,

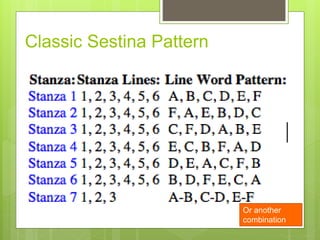

The opening stanza introduces six endwords […]

which repeat through the six sestets. Starting with the

second sestet, each stanza duplicates the previous

stanza’s endwords in the following order: last, first, fifth,

second, fourth, then third. […] By the poem’s end, each

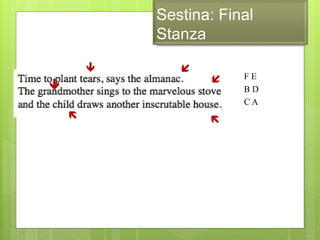

end word appears in all six lines. Finally […] the

concluding [stanza] features two endwords in each of its

three lines, one as an endword and one in the middleof the

line (18).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ewrt30class4-170105032551/85/Ewrt-30-class-4-26-320.jpg)