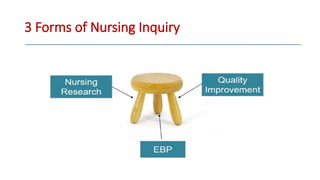

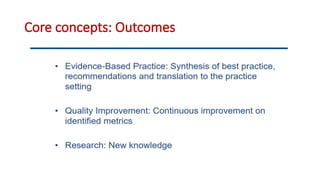

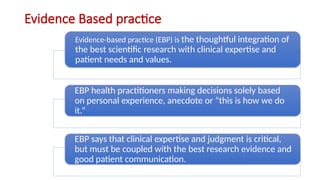

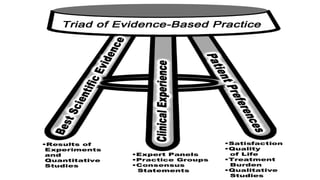

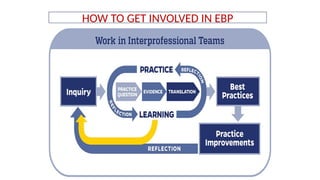

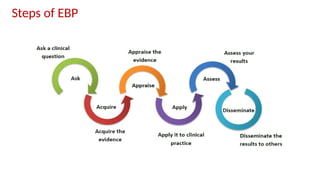

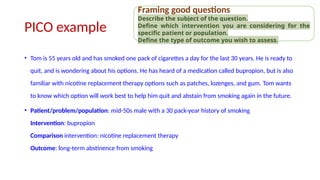

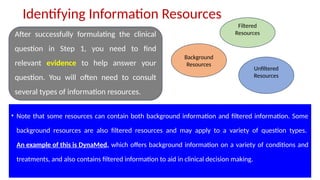

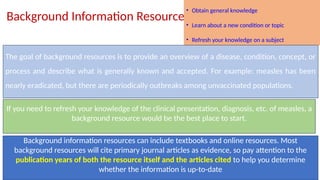

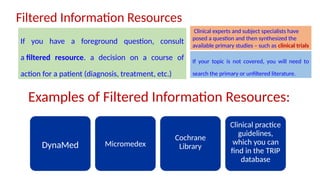

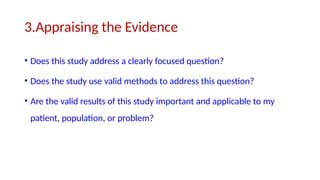

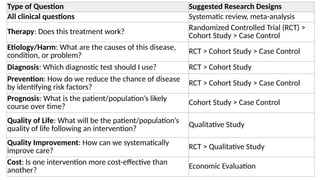

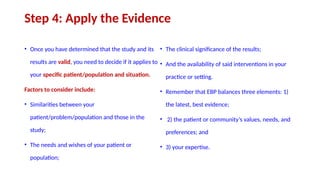

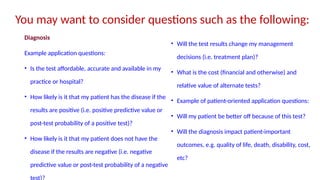

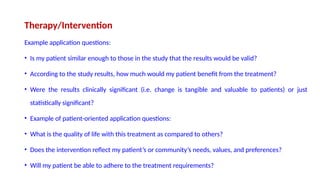

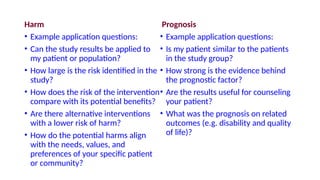

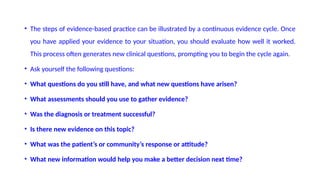

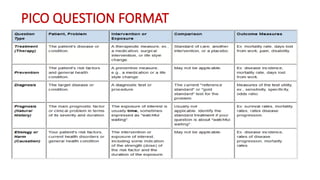

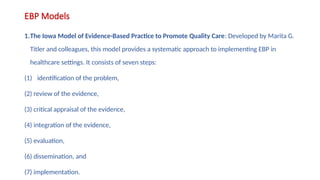

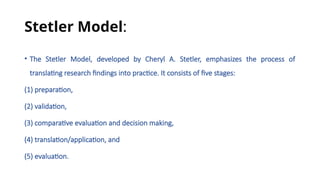

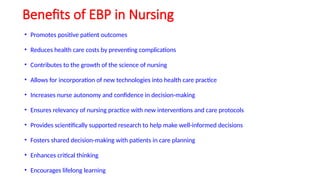

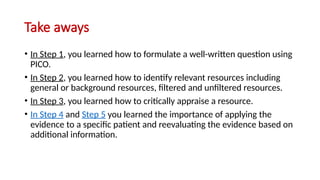

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is the integration of the best available research, clinical expertise, and patient preferences to guide healthcare decisions. It involves asking clinical questions, acquiring and appraising evidence, applying it in practice, and assessing outcomes. EBP improves patient care, safety, and promotes cost-effective, informed decision-making.