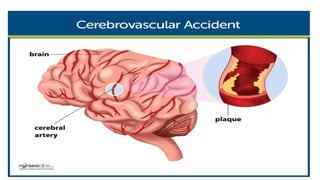

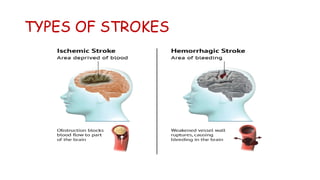

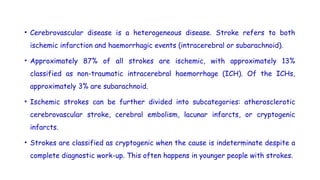

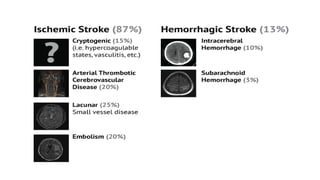

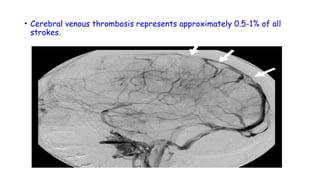

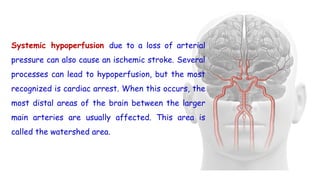

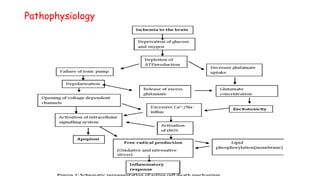

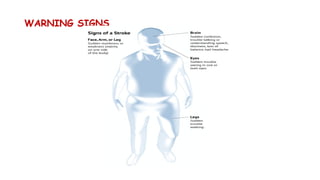

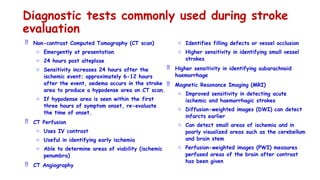

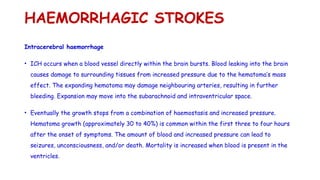

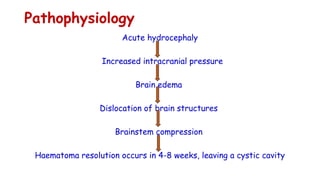

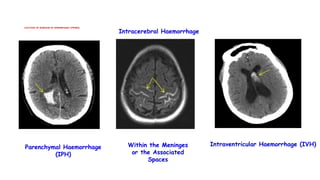

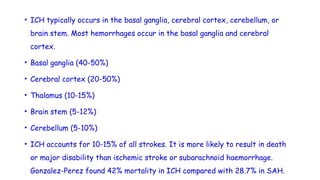

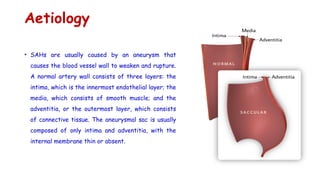

Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), commonly known as strokes, are serious vascular events affecting approximately 795,000 Americans annually, leading to 129,000 deaths each year, and are the foremost cause of long-term disability. Strokes can be divided into ischemic (87%) and hemorrhagic (13%) types, with various risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to each type, including thrombosis and embolism for ischemic strokes. Early intervention through medications like rtPA or endovascular procedures is critical in managing strokes, emphasizing the importance of recognizing warning signs for timely treatment.