This document provides a comprehensive checklist for revising and editing academic essays, covering aspects such as idea organization, coherent writing, appropriate voice and style, and adherence to conventions. It emphasizes the importance of a well-structured argument, including a strong thesis, organized body paragraphs, and effective counterarguments. Additionally, the document outlines resources for further assistance, such as the Purdue Online Writing Lab.

![Check our web site: http://owl.english.purdue.edu

Email brief questions to OWL Mail:

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/contact/owlmailtutors

Where to Go

for More Help

Notes:

The Writing Lab is located on the West Lafayette Campus in

room 226 of Heavilon Hall. The lab is open 9:00am-6:00 pm.

OWL, Online Writing Lab, is a reach resource of information.

Its address is http://owl.english.purdue.edu. And finally, you

can email your questions to OWL Mail at [email protected] and

our tutors will get back to you promptly.

*

The End

ORGANIZING YOUR ARGUMENT

Purdue OWL staff

Brought to you in cooperation with the Purdue Online Writing

Lab

Volume 16, 2017

Accepted by Editor Tian Luo │Received: October 25, 2016│

Revised: March 7, 2017 │ Accepted: March 19,

2017.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-17-2048.jpg)

![Cite as: Reweti, S., Gilbey, A., & Jeffrey, L. (2017). Efficacy of

low-cost pc-based aviation training devices. Jour-

nal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 127-

142. Retrieved from

http://www.informingscience.org/Publications/3682

(CC BY-NC 4.0) This article is licensed to you under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

License. When you copy and redistribute this paper in full or in

part, you need to provide proper attribution to it to ensure

that others can later locate this work (and to ensure that others

do not accuse you of plagiarism). You may (and we encour-

age you to) adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material

for any non-commercial purposes. This license does not

permit you to use this material for commercial purposes.

EFFICACY OF LOW-COST PC-BASED AVIATION

TRAINING DEVICES

Savern Reweti * School Of Aviation, Massey University,

Palmerston North, New Zealand

[email protected]

Andrew Gilbey School Of Aviation, Massey University,

Palmerston North, New Zealand

[email protected]

Lynn Jeffrey School Of Management, Massey University,

Palmerston North, New Zealand

[email protected]

* Corresponding author

ABSTRACT

Aim/Purpose The aim of this study was to explore whether a

full cost flight training device](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-18-2048.jpg)

![for Practitioners

We discuss the possibility that low cost PCATDs may be a

viable alternative for

flight schools wishing to use a flight simulator but not able to

afford a FTD.

http://www.informingscience.org/Publications/3682

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

mailto:[email protected]

Efficacy of Low-Cost PC-Based Aviation Training Devices

128

Recommendation

for Researchers

We discuss the introduction of improved low cost technologies

that allow

PCATDs to be used more effectively for training in VFR

procedures. The de-

velopment and testing of new technologies requires more

research.

Impact on Society Flight training schools operate in a difficult

economic environment with contin-

ued increases in the cost of aircraft maintenance, compliance

costs, and aviation

fuel. The increased utilisation of low cost PCATD’s especially

for VFR instruc-

tion could significantly reduce the overall cost of pilot training

Future Research A new study is being undertaken to compare](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-20-2048.jpg)

![Aeronautical Science [Unpublished], Embry-Riddle

Aeronautical University, Spangdahlem, Germany

Smith, J. K., & Caldwell, J. A. (2004). Methodology for

evaluating the simulator flight performance of pilots.

Retrieved 11

November 2014, from

https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/

ADA429740.xhtml

Stewart, J. E., II,. Dohme, J. A., & Nullmeyer, R. T. (2002). US

Army initial entry rotary-wing transfer of train-

ing research. International Journal of Aviation Psychology,

12(4), 359-375.

Talleur, D. A., Taylor, H. L., Emanuel, T. W., Rantanen, E., &

Bradshaw, G. L. (2003). Personal computer avia-

tion training devices: Their effectiveness for maintaining

instrument currency. International Journal of Avia-

tion Psychology, 13(4), 387-399.

Taylor, H. L., Lintern, G., Hulin, C. L., Talleur, D. A.,

Emanuel, T. W., & Phillips, S. I. (1999). Transfer of train-

ing effectiveness of a personal computer aviation training

device. The International Journal of Aviation Psychol-

ogy, 9(4), 319-335.

Taylor, H. L., Lintern, G., & Koonce, J. M. (1993). Quasi-

transfer as a predictor of transfer from simulator to

airplane. The Journal of General Psychology, 120(3), 257-276.

Taylor, H. L., Talleur, D. A., Emanuel, T. W. J., Rantanen, E.

M., Bradshaw, G. L., & Phillips, S. I. (2003). Incre-

mental training effectiveness of personal computers used for

instrument training. Paper presented at the 12th Interna-

tional Symposium on Aviation Psychology, Dayton Ohio.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-64-2048.jpg)

![Attitude and Motivation through the Application of Content and

Language Integrated Learning.

International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 751-766.

https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12148a

Received: 29/07/2018

Revision: 17/11/2018

Accepted: 20/11/2018

OnlineFirst: 23/11/2018

Enhancing Pilot’s Aviation English Learning, Attitude and

Motivation

through the Application of Content and Language Integrated

Learning

Parvin Karimi

Faculty of English Language Department, Islamic Azad

University Isfahan (Khorasgan

Branch). Isfahan, Iran, [email protected]

Ahmad Reza Lotfi

Asst. Prof., Faculty of English Language Department, Islamic

Azad University Isfahan

(Khorasgan Branch). Isfahan, Iran, [email protected]

Reza Biria

Assoc. Prof., Faculty of English Language Department, Islamic

Azad University Isfahan

(Khorasgan Branch). Isfahan, Iran, [email protected]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-69-2048.jpg)

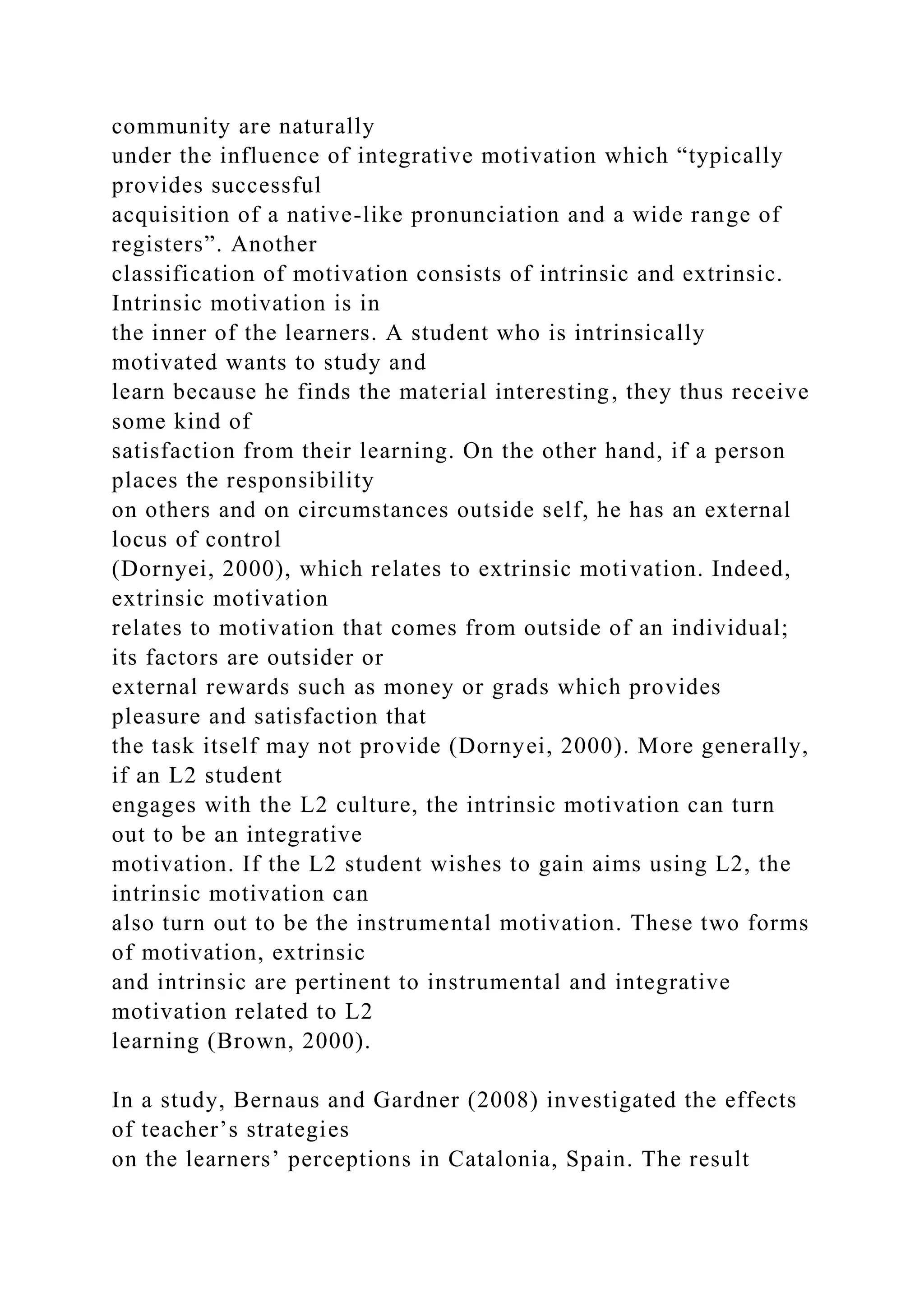

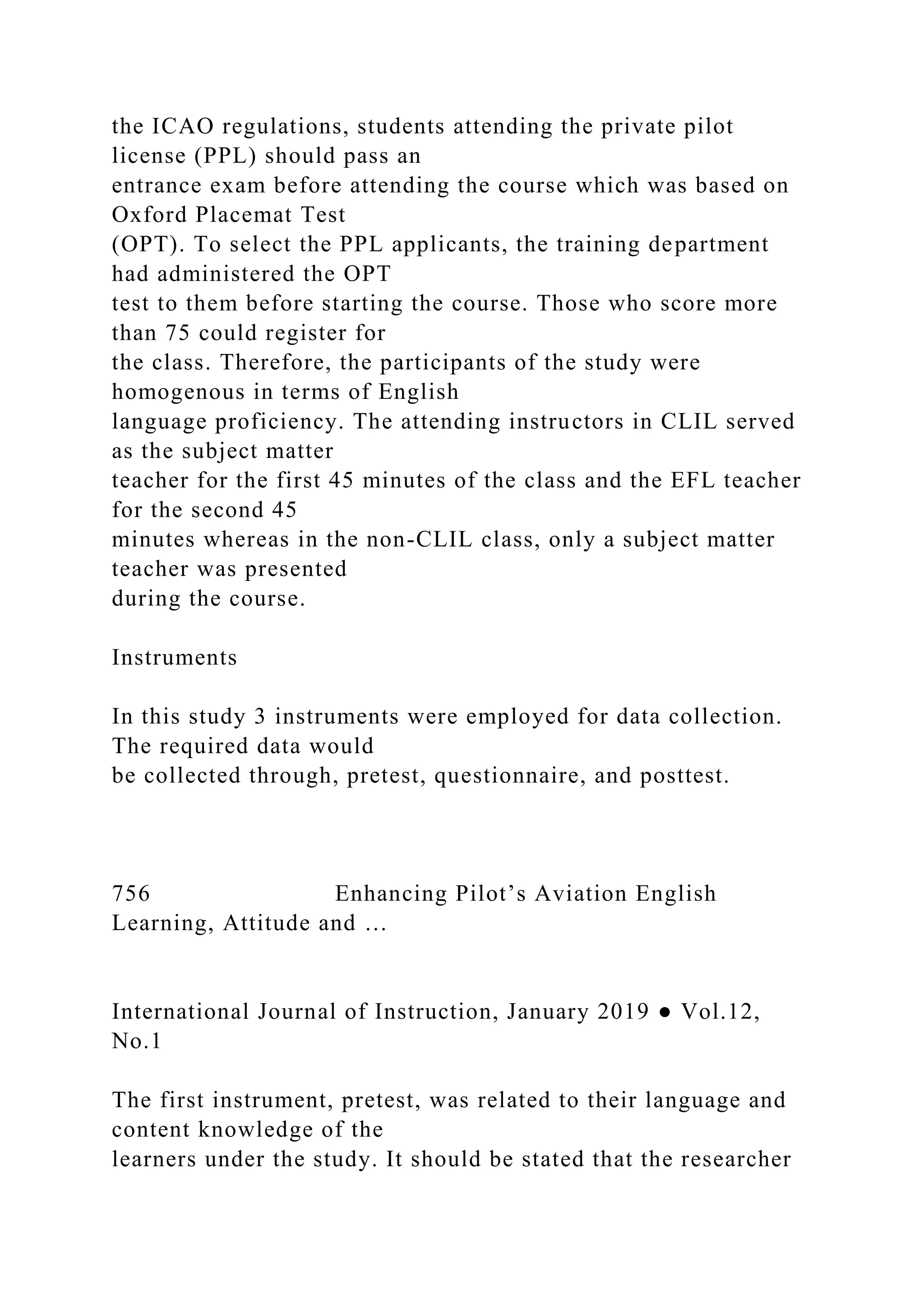

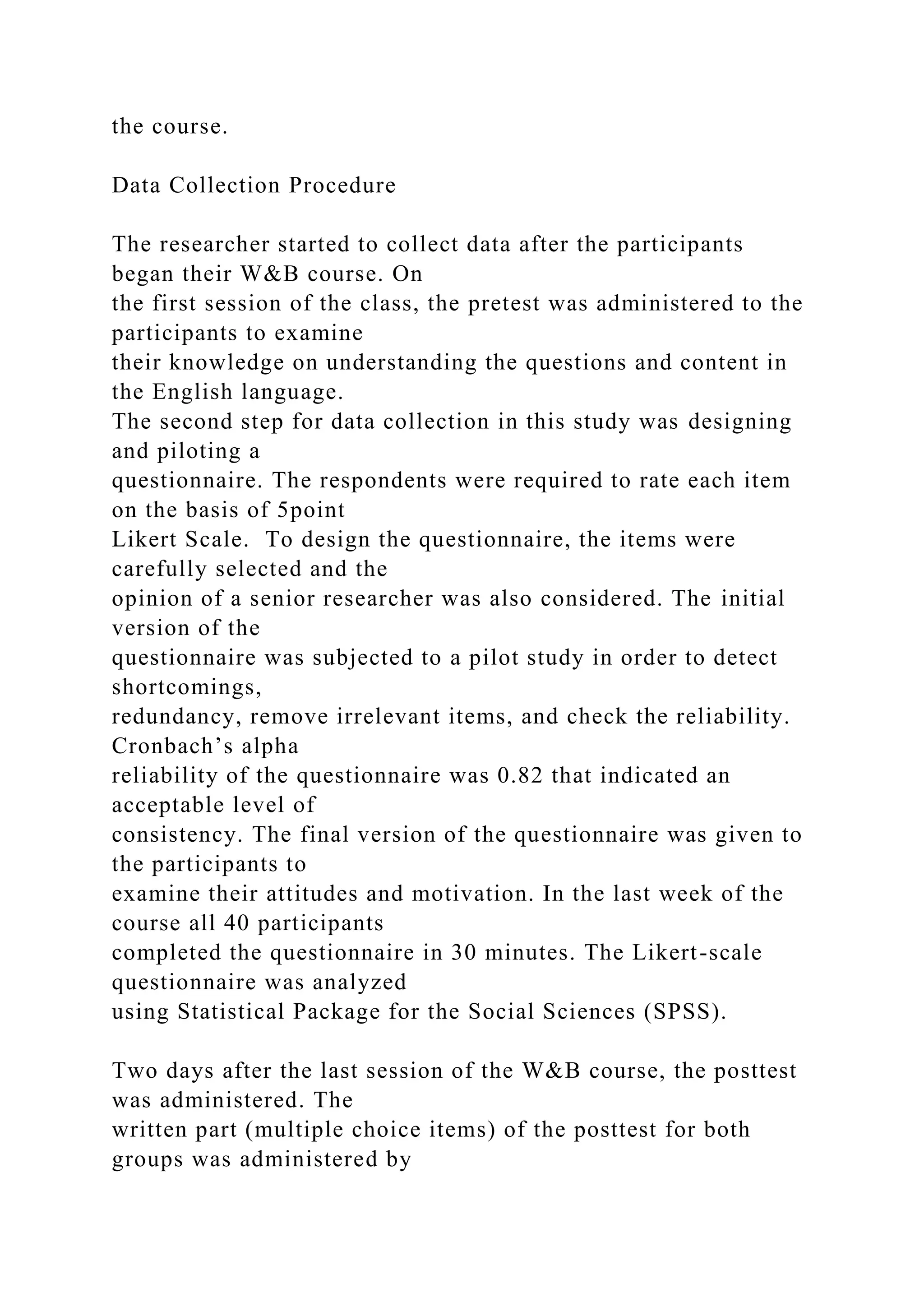

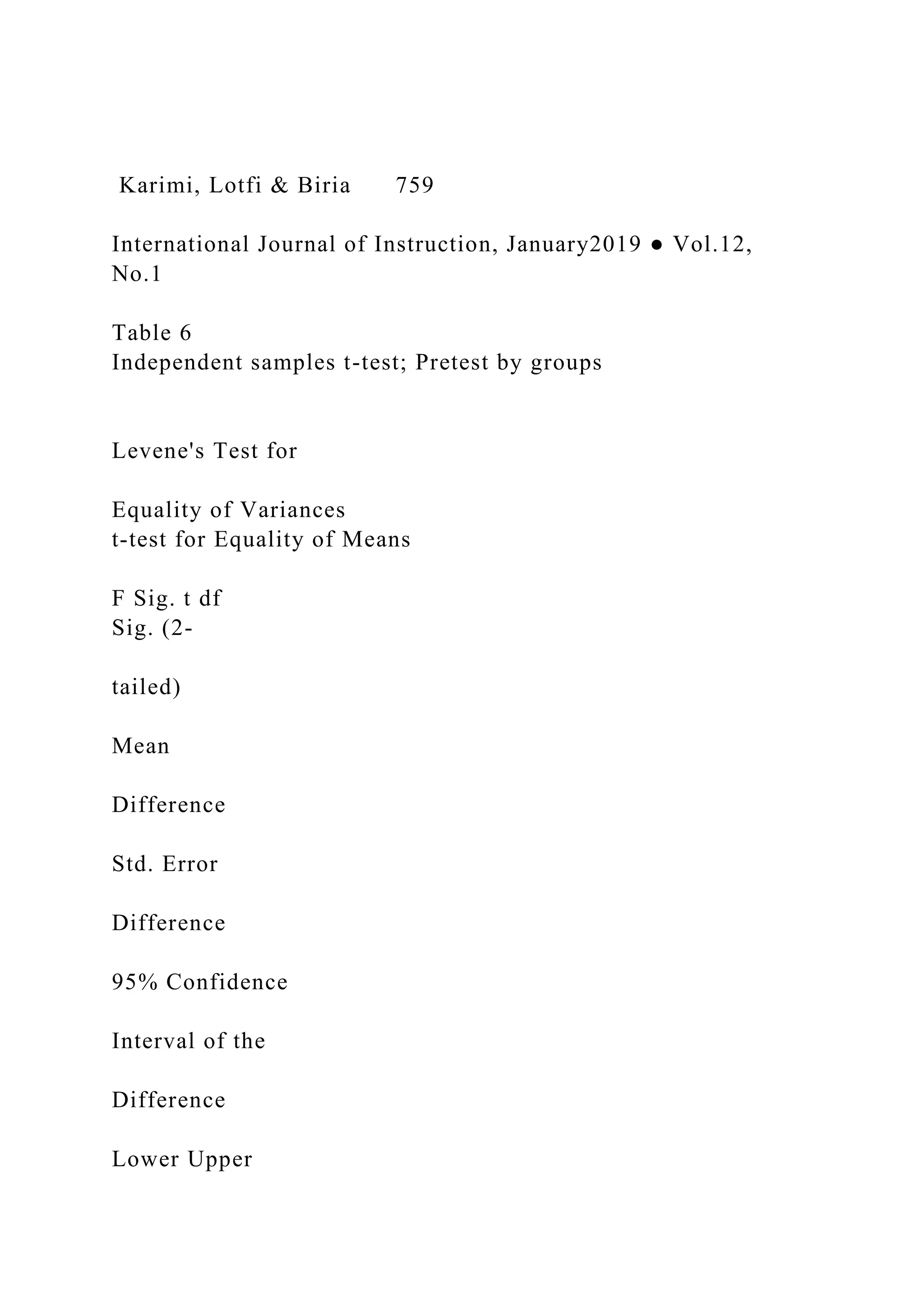

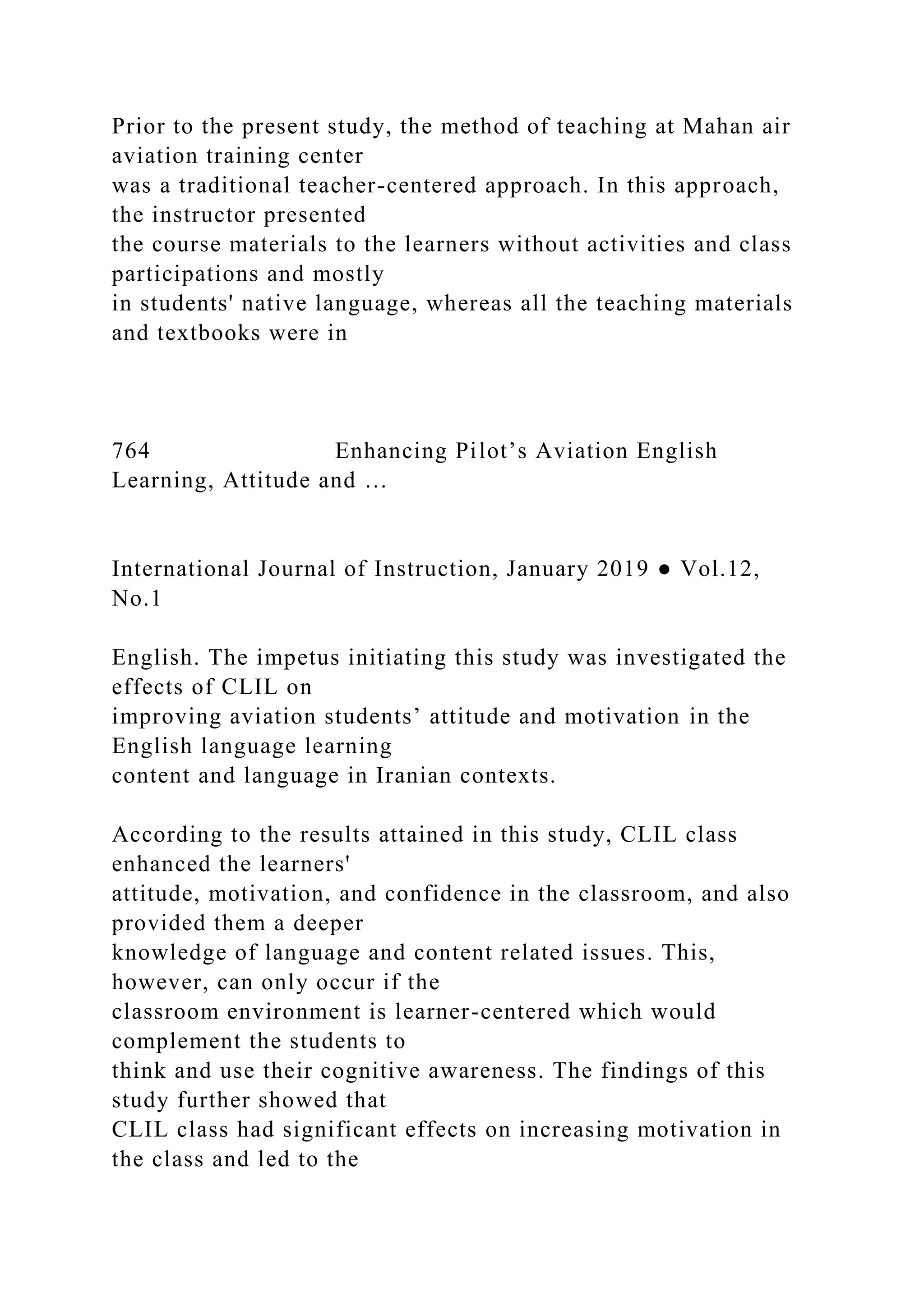

![Homogenizing Groups on Pretest

An independent t-test was run to compare the CLIL and non-

CLIL groups’ means on the

pretest. Based on the results displayed in Table 5, the CLIL (M

= 64.85, SD = 9.31) and

non-CLIL (M = 63.85, SD = 9.36) groups had fairly close means

on the pretest.

Table 5

Descriptive statistics; pretest

Group n M SD Std. Error Mean

Pret

est

CLIL 20 64.85 9.315 2.083

Non-CLIL 20 63.85 9.366 2.094

The results of the independent t-test (t (29) = .339, 95 % CI [-

4.97, 6.97], p = .737, r =

.055 representing a weak effect size) (Table 6) indicated that

the groups were

homogenous in terms of their language and content knowledge

as measured through the

pretest.

It should be noted that the assumption of homogeneity of

variances was met (Levene’s F

= .001, p = 1.00). That is why the first row of Table 6, i.e.

“Equal variances not

assumed” was reported.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-88-2048.jpg)

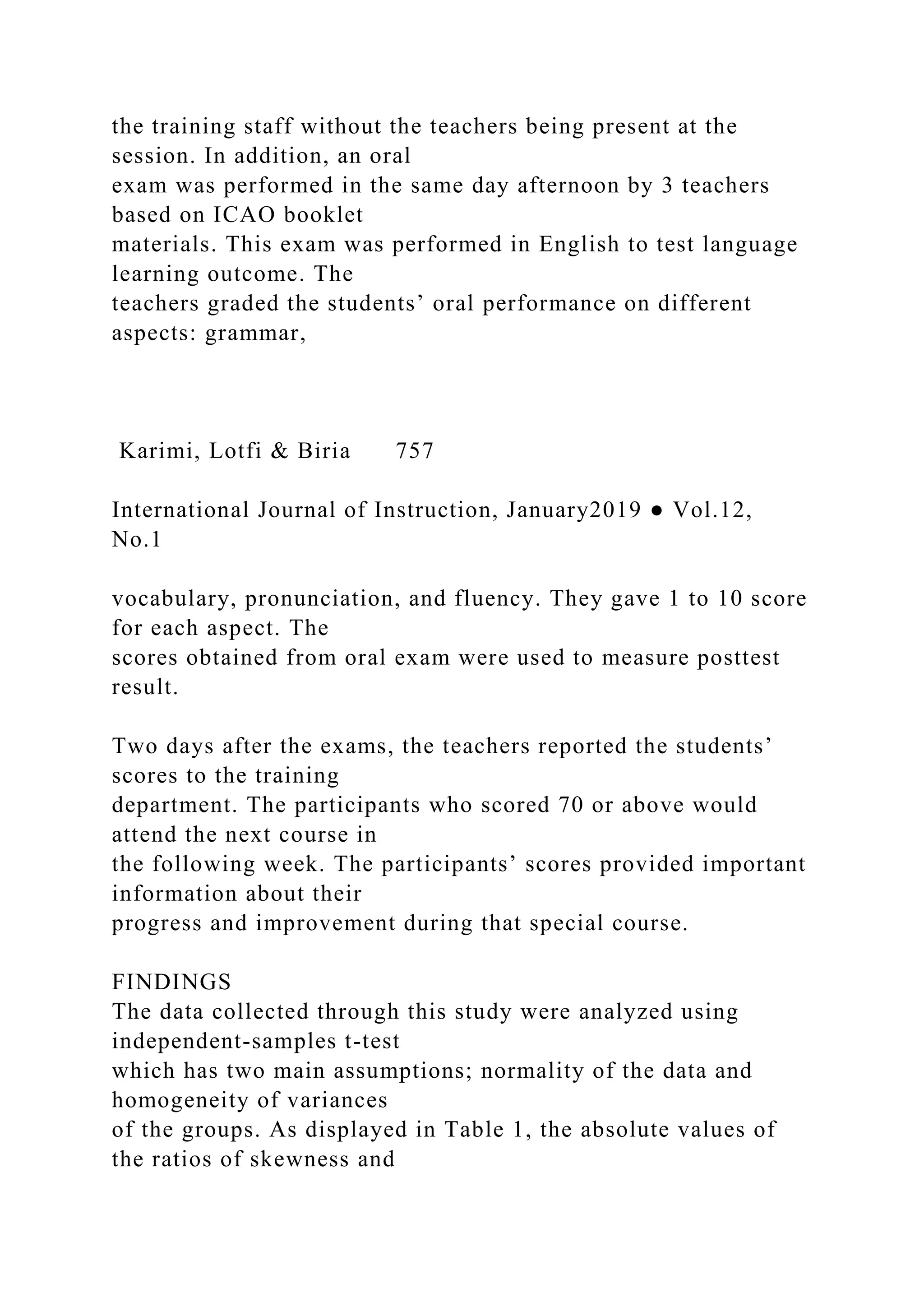

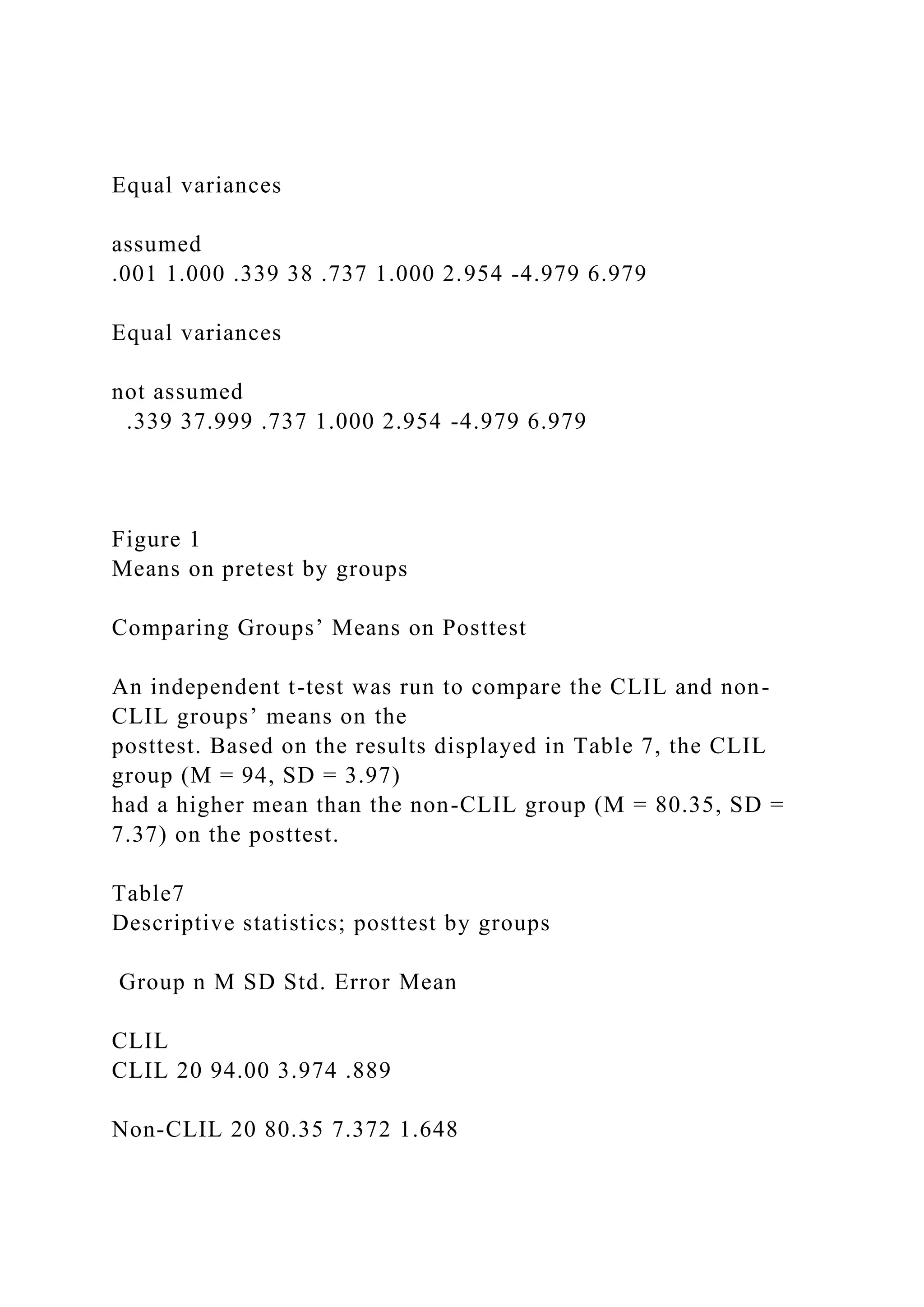

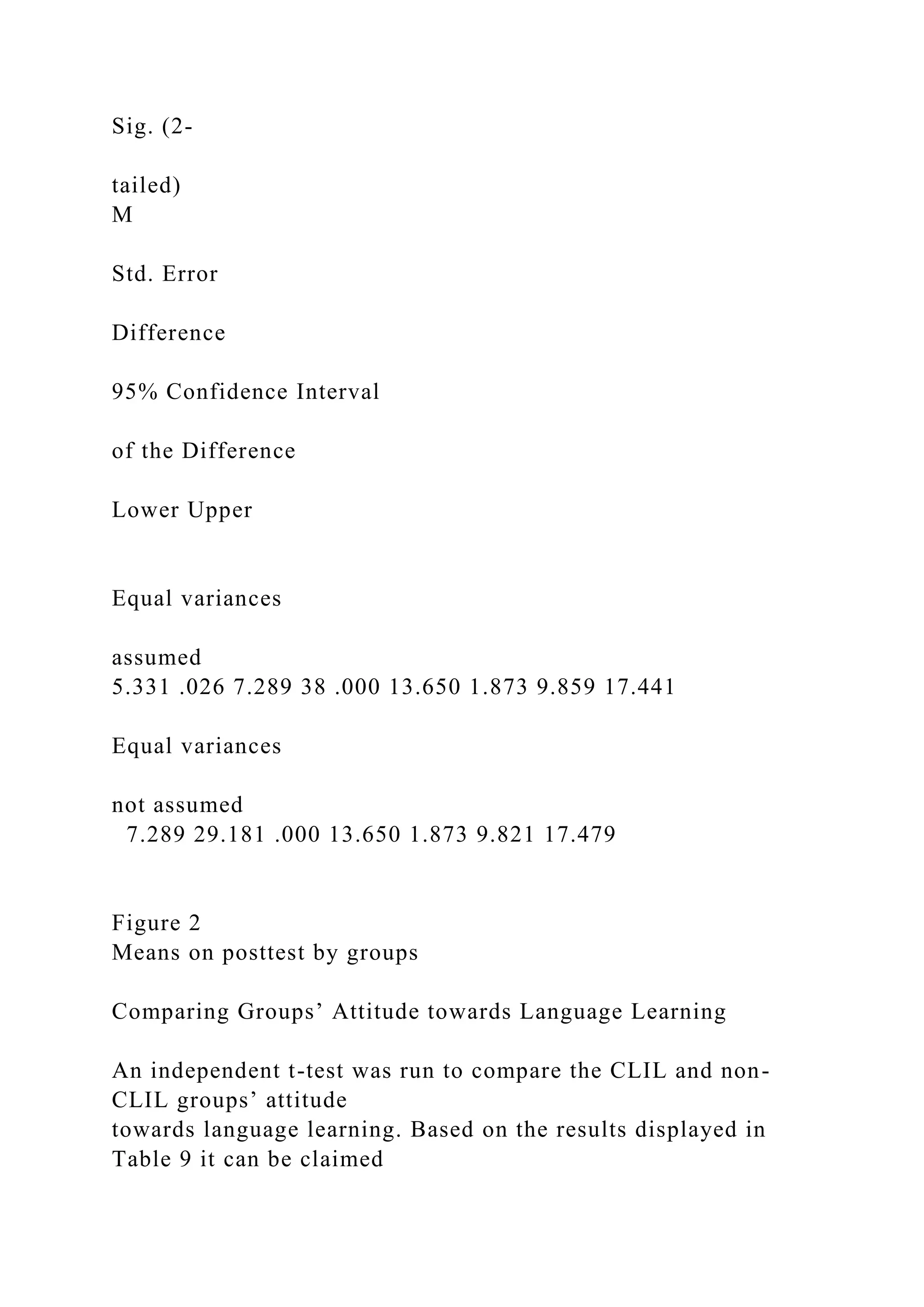

![The results of the independent t-test (t (29) = 7.28, 95 % CI

[9.82, 17.47], p = .000, r =

.804 representing a large effect size) (Table 7) indicated that

the CLIL significantly

outperformed the non-CLIL group on the posttest. Thus the

null-hypothesis was

rejected. The CLIL method significantly enhanced the Aviation

English learning of

Iranian pilots through the application of content and language

integrated learning.

It should be noted that the assumption of homogeneity of

variances was not met

(Levene’s F = 5.33, p = .026). That is why the second row of

Table 8, i.e. “Equal

variances not assumed” was reported.

760 Enhancing Pilot’s Aviation English

Learning, Attitude and …

International Journal of Instruction, January 2019 ● Vol.12,

No.1

Table 8

Independent samples t-test; posttest

Levene's Test for

Equality of Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-91-2048.jpg)

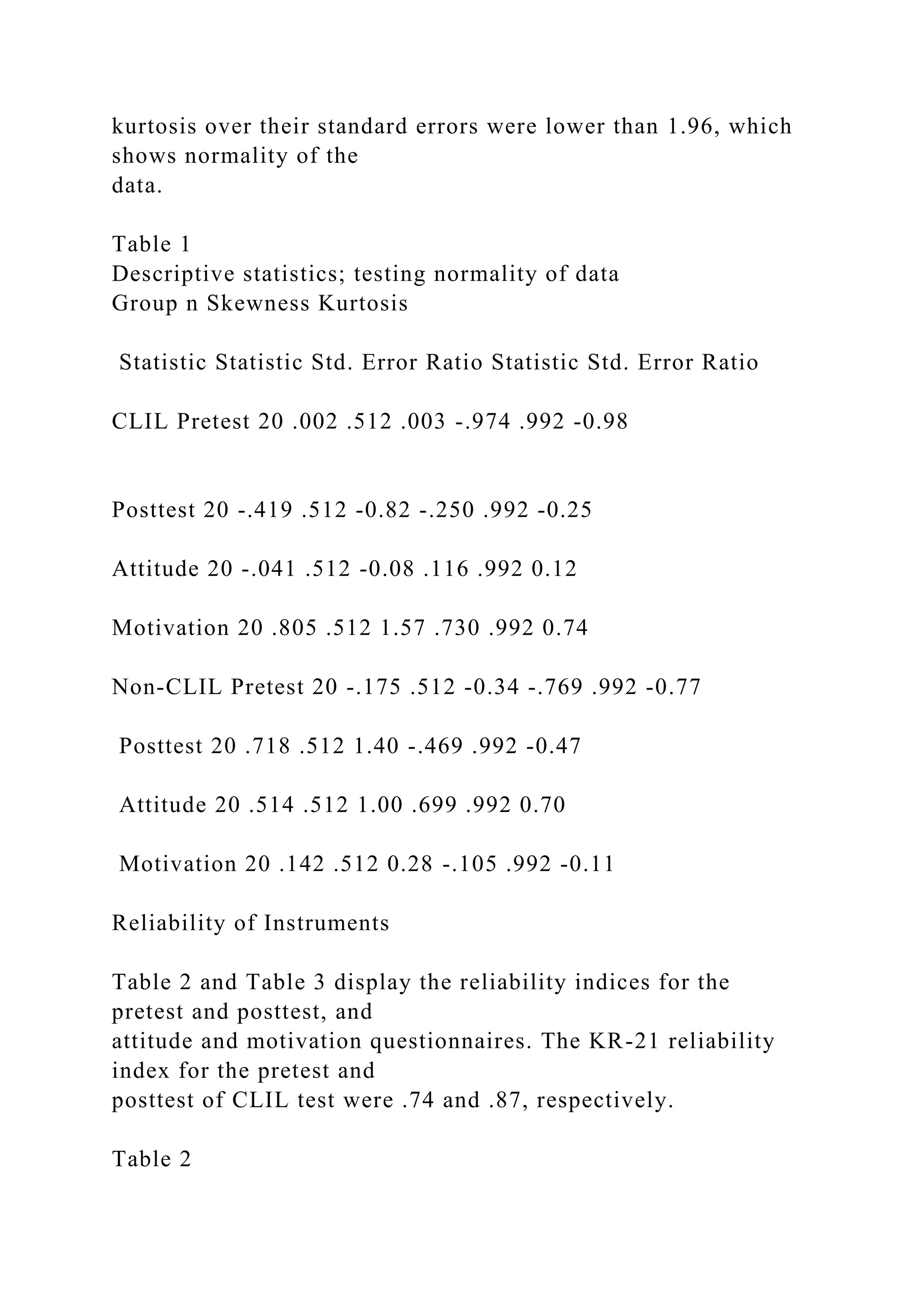

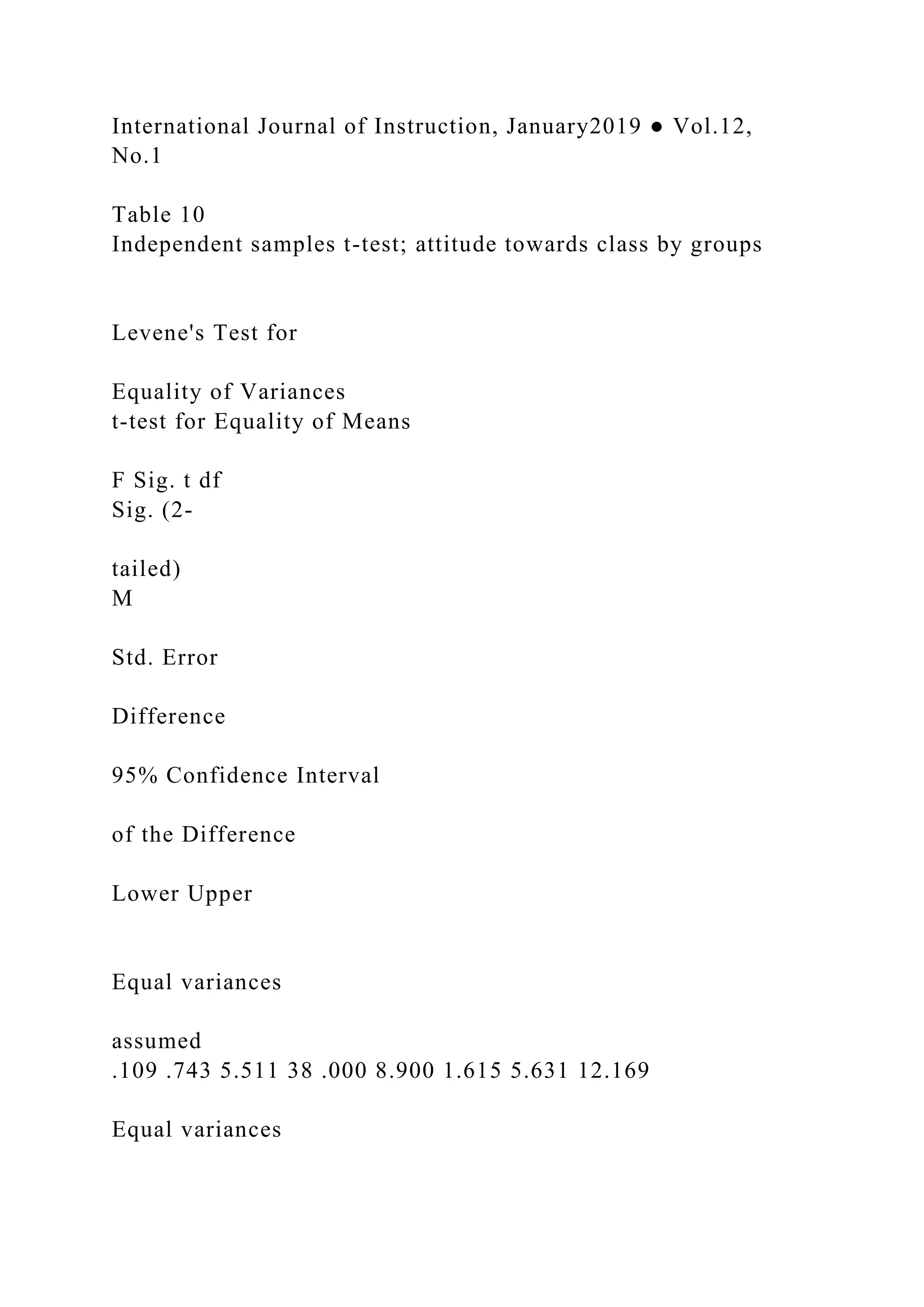

![that the CLIL group (M = 40.60, SD = 5.25) showed a more

positive attitude towards

language learning than the non-CLIL group (M = 31.70, SD =

4.95).

Table 9

Descriptive statistics; attitude towards language learning

Group n M SD Std. Error Mean

Attitude

CLIL 20 40.60 5.256 1.175

Non-CLIL 20 31.70 4.953 1.108

The results of the independent t-test (t (38) = 5.51, 95 % CI

[5.63, 12.16], p = .000, r =

.666 representing a large effect size) (Table 10) indicated that

the CLIL significantly

had a more positive attitude towards language learning than the

non-CLIL group. Thus

the null-hypothesis was rejected.

It should be noted that the assumption of homogeneity of

variances was retained

(Levene’s F = .109, p = .743). That is why the first row of Table

10, i.e. “Equal

variances assumed” was reported.

Karimi, Lotfi & Biria 761](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-93-2048.jpg)

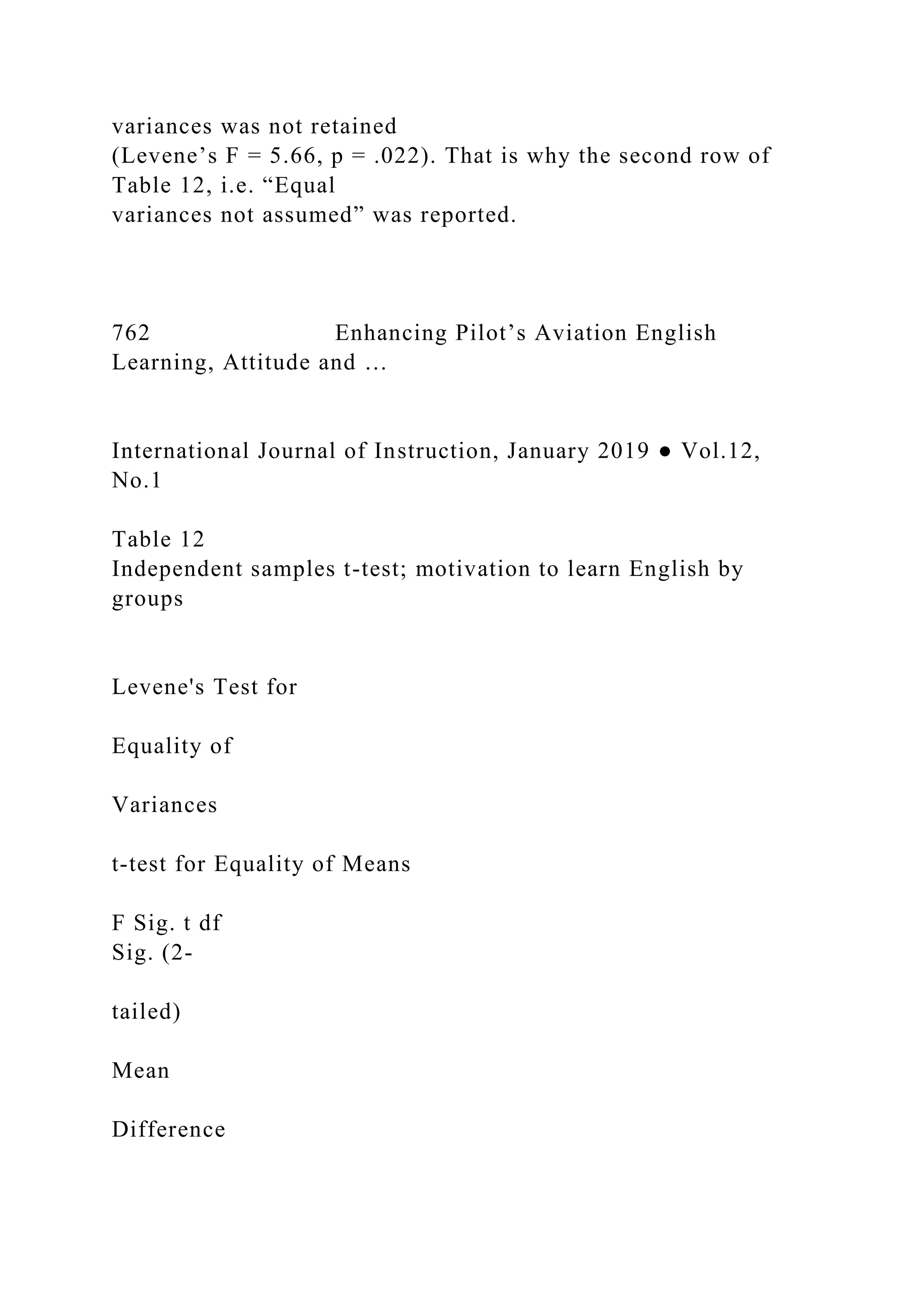

![not assumed

5.511 37.868 .000 8.900 1.615 5.630 12.170

Figure 3

Means on attitude towards language learning by groups

Comparing Groups’ Motivation to Learn English

An independent t-test was run to compare the CLIL and non-

CLIL groups’ motivation to

learn English. Based on the results displayed in Table 11 it can

be claimed that the CLIL

group (M = 42, SD = 9.45) were more motivated to learn

English than the non-CLIL

group (M = 32.60, SD = 5.25).

Table 11

Descriptive statistics; motivation to learn English by groups

Group n M SD Std. Error Mean

Motivation

CLIL 20 42.00 9.459 2.115

Non-CLIL 20 32.60 5.256 1.175

The results of the independent t-test (t (29) = 3.88, 95 % CI

[4.50, 14.29], p = .000, r =

.585 representing a large effect size) (Table 12) indicated that

the CLIL significantly

had higher motivation to learn English than the non-CLIL

group. Thus the null-

hypothesis was rejected.

It should be noted that the assumption of homogeneity of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-95-2048.jpg)

![Doi: 10.2501/JAr-2021-013 september 2021 JOURNAL OF

ADVERTISING RESEARCH 245

Editor’s Desk

New Insights on Advertising Execution

And Consumer Engagement

JOHN B. FORD

Editor-in-chief,

Journal of Advertising

Research

Eminent scholar and

Professor of marketing

and international

Business,

strome college of

Business, old Dominion

university

[email protected]

Text variables

Enter text variables here to define ruuning](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-107-2048.jpg)

![However, one part of American life was affected that is quite

often taken for granted: the

life of the American farmer.

Population and Technological Changes. One of the biggest

changes, as seen in

nineteenth century America’s census reports, is the dramatic

increase in population. The

1820 census reported that over 10 million people were living in

America; of those 10

million, over 2 million were engaged in agriculture. Ten years

prior to that, the 1810

census reported over 7 million people were living in the states;

there was no category for

people engaged in agriculture. In this ten-year time span, then,

agriculture experienced

significant improvements and changes that enhanced its

importance in American life.

One of these improvements was the developments of canals and

steamboats,

which allowed farmers to “sell what has previously been

unsalable [sic]” and resulted in a

If there is a

gramma-

tical,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-122-2048.jpg)

![mechanical,

or spelling

error in the

text you are

citing, type

the quote as

it appears.

Follow the

error with

“[sic].”

The

paragraph

after the

Level 2

headers

start flush

left after

the

headings.

Use

another

style, e.g.,

italics, to

differen-

tiate the

Level 3

headers

from the

Level 2

headers.

The

paragraph

continues

directly](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-123-2048.jpg)

![after the

header.

Headings,

though not

required by

MLA style,

can help the

overall

structure and

organization

of a paper.

Use them at

your

instructor’s

discretion to

help your

reader follow

your ideas.

Use

personal

pronouns

(I, we, us,

etc.) at

your

instructor’s

discretion.

Angeli 3

“substantial increase in [a farmer’s] ability to earn income”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-124-2048.jpg)

![The Distribution of New Knowledge. Before 1820 and prior to

the new knowledge

farmers were creating, farmers who wanted print information

about agriculture had their

choice of agricultural almanacs and even local newspapers to

receive information

(Danhof 54). After 1820, however, agricultural writing took

more forms than almanacs

and newspapers. From 1820 to 1870, agricultural periodicals

were responsible for

spreading new knowledge among farmers. In his published

dissertation The American

Agricultural Press 1819-1860, Albert Lowther Demaree presents

a “description of the

general content of [agricultural journals]” (xi). These journals

began in 1819 and were

written for farmers, with topics devoted to “farming, stock

raising, [and] horticulture”

(12). The suggested “birthdate” of American agricultural

journalism is April 2, 1819

when John S. Skinner published his periodical American Farmer

in Baltimore. Demaree

writes that Skinner’s periodical was the “first continuous,

successful agricultural](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-129-2048.jpg)

![was the “need for acquiring scientific information upon which

could be based a rational

technology” that could “be substituted for the current diverse,

empirical practices”

(Danhof 69). In his 1825 book Nature and Reason Harmonized

in the Practice of

Husbandry, John Lorain begins his first chapter by stating that

“[v]ery erroneous theories

have been propagated” resulting in faulty farming methods (1).

His words here create a

framework for the rest of his book, as he offers his readers

narratives of his own trials and

errors and even dismisses foreign, time-tested techniques

farmers had held on to: “The

knowledge we have of that very ancient and numerous nation

the Chinese, as well as the

very located habits and costumes of this very singular people, is

in itself insufficient to

teach us . . .” (75). His book captures the call and need for

scientific experiments to

develop new knowledge meant to be used in/on/with American

soil, which reflects some

farmers’ thinking of the day.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-133-2048.jpg)

![name and

page

number)

follows the

quote’s end

punctua-

tion.

Angeli 6

Part of Nicholson’s hope was realized in 1837 when Michigan

established their state

university, specifying that “agriculture was to be an integral

part of the curriculum”

(Danhof 71). Not much was accomplished, however, much to

the dissatisfaction of

farmers, and in 1855, the state authorized a new college to be

“devoted to agriculture and

to be independent of the university” (Danhof 71). The

government became more involved

in the creation of agricultural universities in 1862 when

President Lincoln passed the

Morrill Land Grant College Act, which begins with this phrase:

“AN ACT Donating

Public Lands to the several States and Territories which may

provide Colleges for the

Benefit of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts [sic].” The first](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-136-2048.jpg)

![agricultural colleges formed

under the act suffered from a lack of trained teachers and “an

insufficient base of

knowledge,” and critics claimed that the new colleges did not

meet the needs of farmers

(Hurt 193).

Congress addressed these problems with the then newly formed

United States

Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA and Morrill Act

worked together to form

“. . . State experiment stations and extension services . . . [that]

added [to]

. . . localized research and education . . .” (Baker et al. 415).

The USDA added to the

scientific and educational areas of the agricultural field in other

ways by including

research as one of the organization’s “foundation stone” (367)

and by including these

seven objectives:

(1) [C]ollecting, arranging, and publishing statistical and other

useful

agricultural information; (2) introducing valuable plants and

animals; (3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-137-2048.jpg)

![Practical Treatise on Soils, Manures, Draining, Irrigation,

Grasses, Grain,

Roots, Fruits, Cotton, Tobacco, Sugar Cane, Rice, and Every

Staple Product of

the United States with the Best Methods of Planting,

Cultivating, and Preparation

for Market. Saxton, 1849.

Baker, Gladys L., et al. Century of Service: The First 100 Years

of the United States

Department of Agriculture. [Federal Government], 1996.

Danhof, Clarence H. Change in Agriculture: The Northern

United States, 1820-1870.

Harvard UP, 1969.

Demaree, Albert Lowther. The American Agricultural Press

1819-1860. Columbia UP,

1941.

Drown, William, and Solomon Drown. Compendium of

Agriculture or the Farmer’s

Guide, in the Most Essential Parts of Husbandry and Gardening;

Compiled from

the Best American and European Publications, and the

Unwritten Opinions of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-143-2048.jpg)

![issue before concluding the essay. Many of these factors will be

determined by the assignment.”

Argumentative Research Essay 6

USE OF INTERNET SOURCES: The INTERNET can provide

you with valuable sources if used properly. In order to use an

INTERNET source, you must save an electronic copy of the

page and document the web site address. Given the variability

of the value and reliability of internet sources, in order to use a

general website, it has to rank highly on the INFORMATION

SOURCE EVALUATION MATRIX (document available on

Moodle site).

BOOKS: Certain topics are more amenable to the use of books

as sources. You may use books as long as they are relevant,

appropriate in academic level, and use valid research.

PRACTICAL ADVICE FOR WRITING: When citing source

information in your research essay, keep the following advice in

mind:

--> Never let a quote stand alone as a sentence or a paragraph.

You should introduce it by contextualizing it. For instance, you

can mention the source of the quote and why the source is

significant.

Joan Collins, a medical researcher at Johns Hopkins University

and author of Dealing with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders,

explains, “ [fill in quote here]. . .” (37).

The number 37 in parenthesis indicates the page number the

quote was found on. Since the author’s name is mentioned, it is

not necessary to repeat it in parenthesis.

--> Follow-up a quote with commentary on the relevance to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/essayrevisionandeditingchecklistforacademicessaysu-230108104224-0546f7c7/75/Essay-Revision-and-Editing-Checklist-for-Academic-Essays-U-docx-154-2048.jpg)