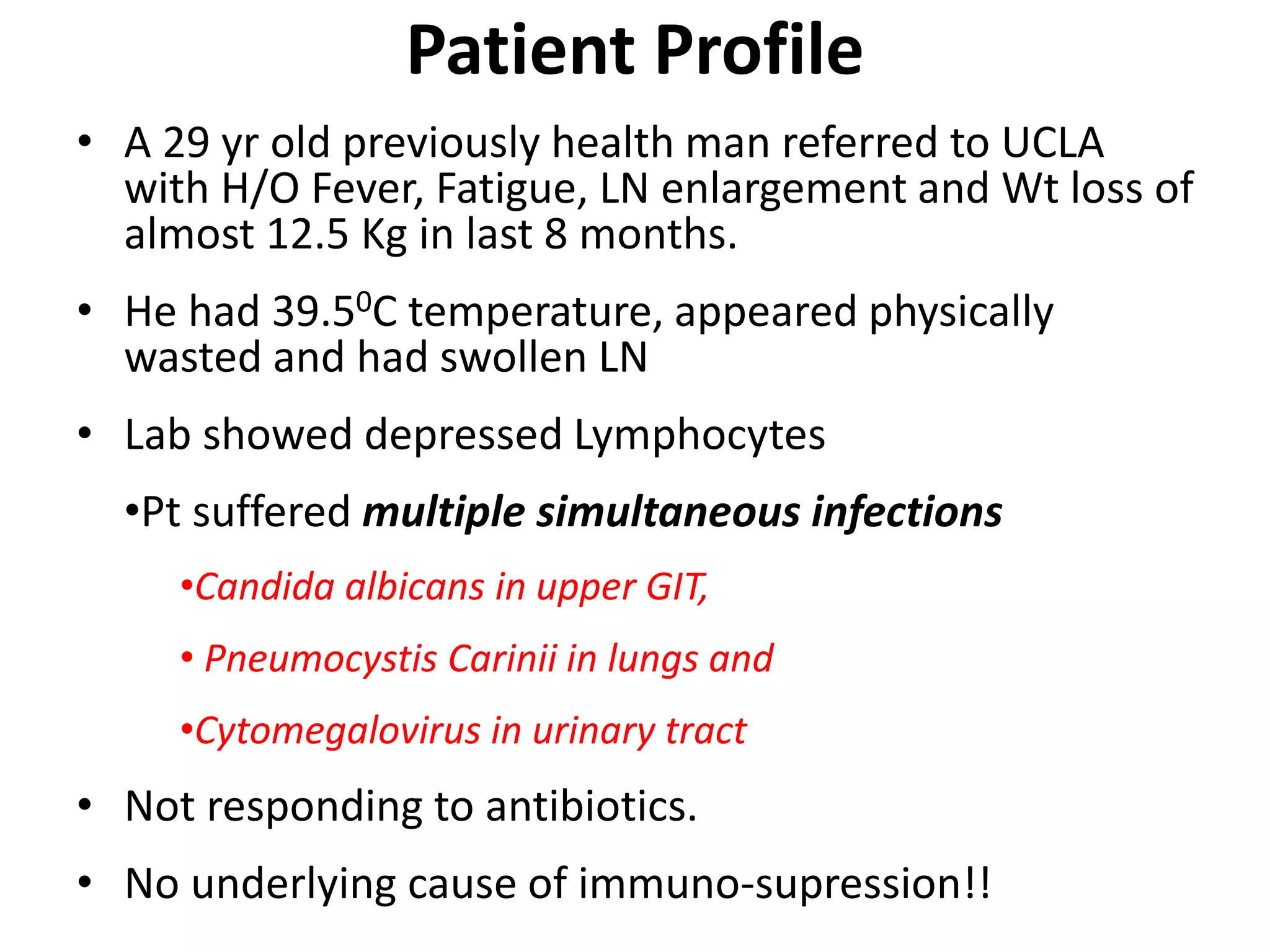

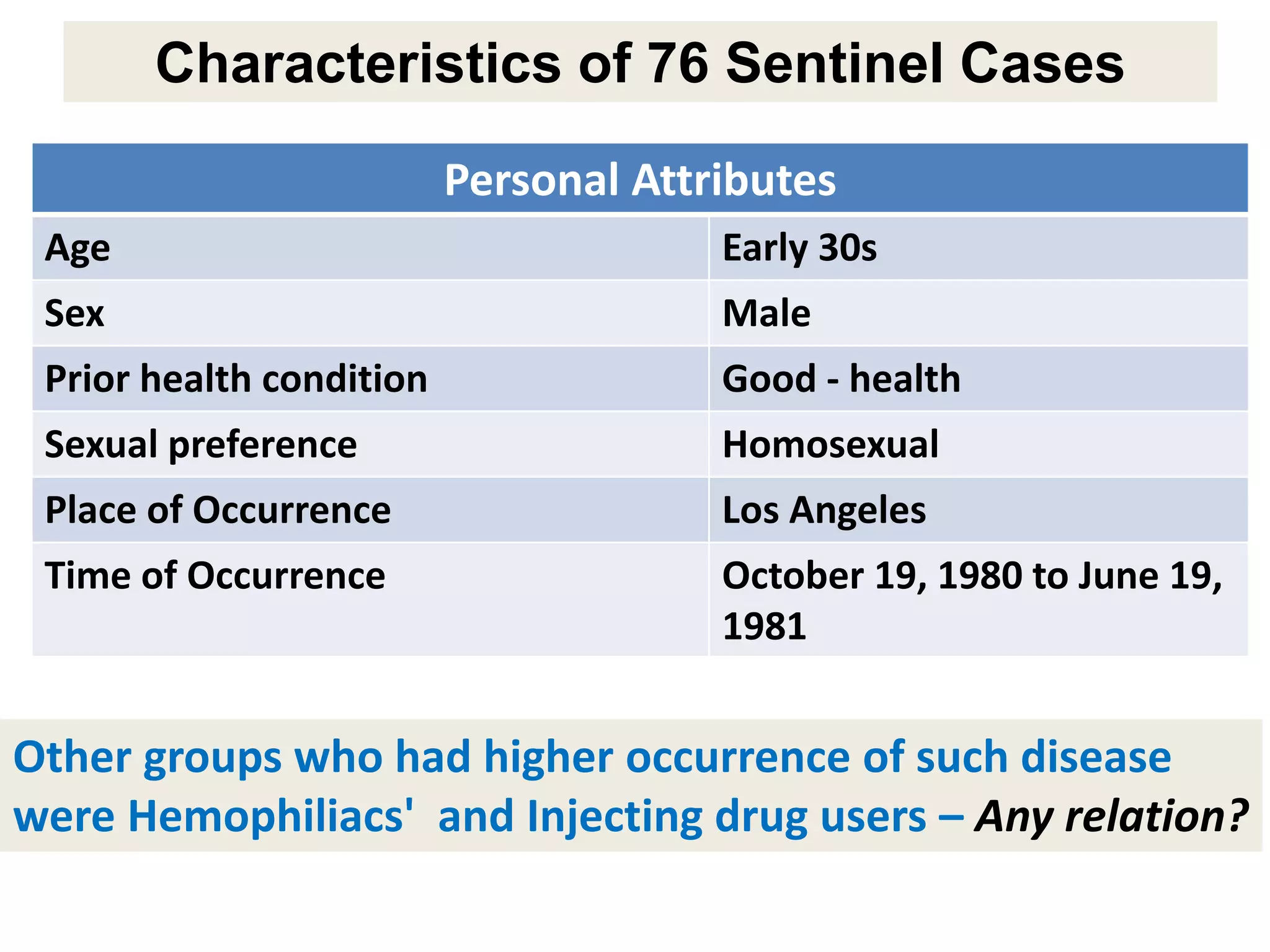

A 29-year-old previously healthy man was referred to UCLA with a 8-month history of fever, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes, and a 12.5 kg weight loss. He had a fever of 39.5°C, appeared physically wasted, and had swollen lymph nodes. Laboratory tests showed depressed lymphocytes. The patient suffered from simultaneous infections of Candida albicans in the upper gastrointestinal tract, Pneumocystis carinii in the lungs, and cytomegalovirus in the urinary tract, and was not responding to antibiotics with no known cause of immunosuppression. There were also 3 other previously healthy young men in the last 6 months reported with similar symptoms who all had Candida albic