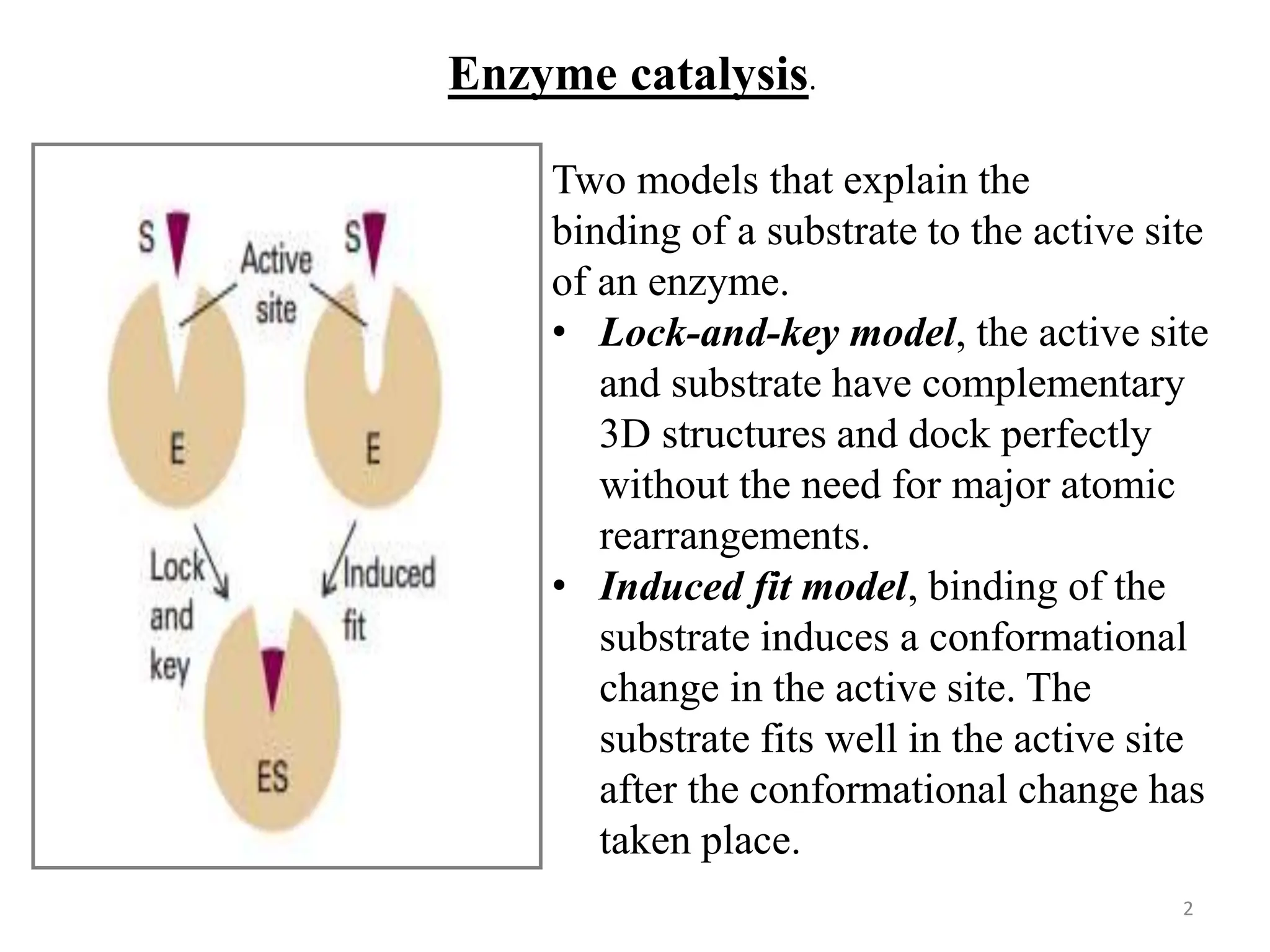

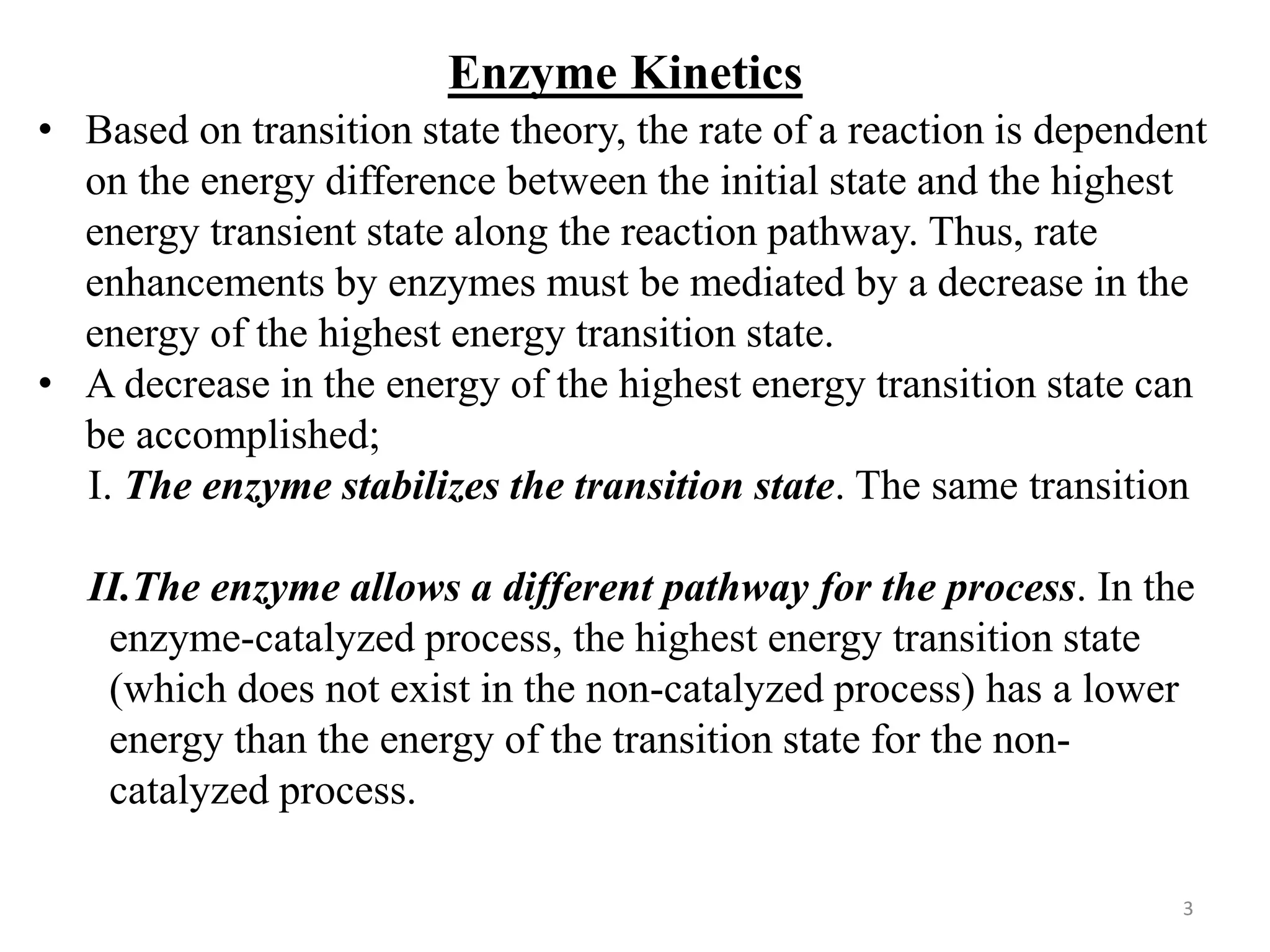

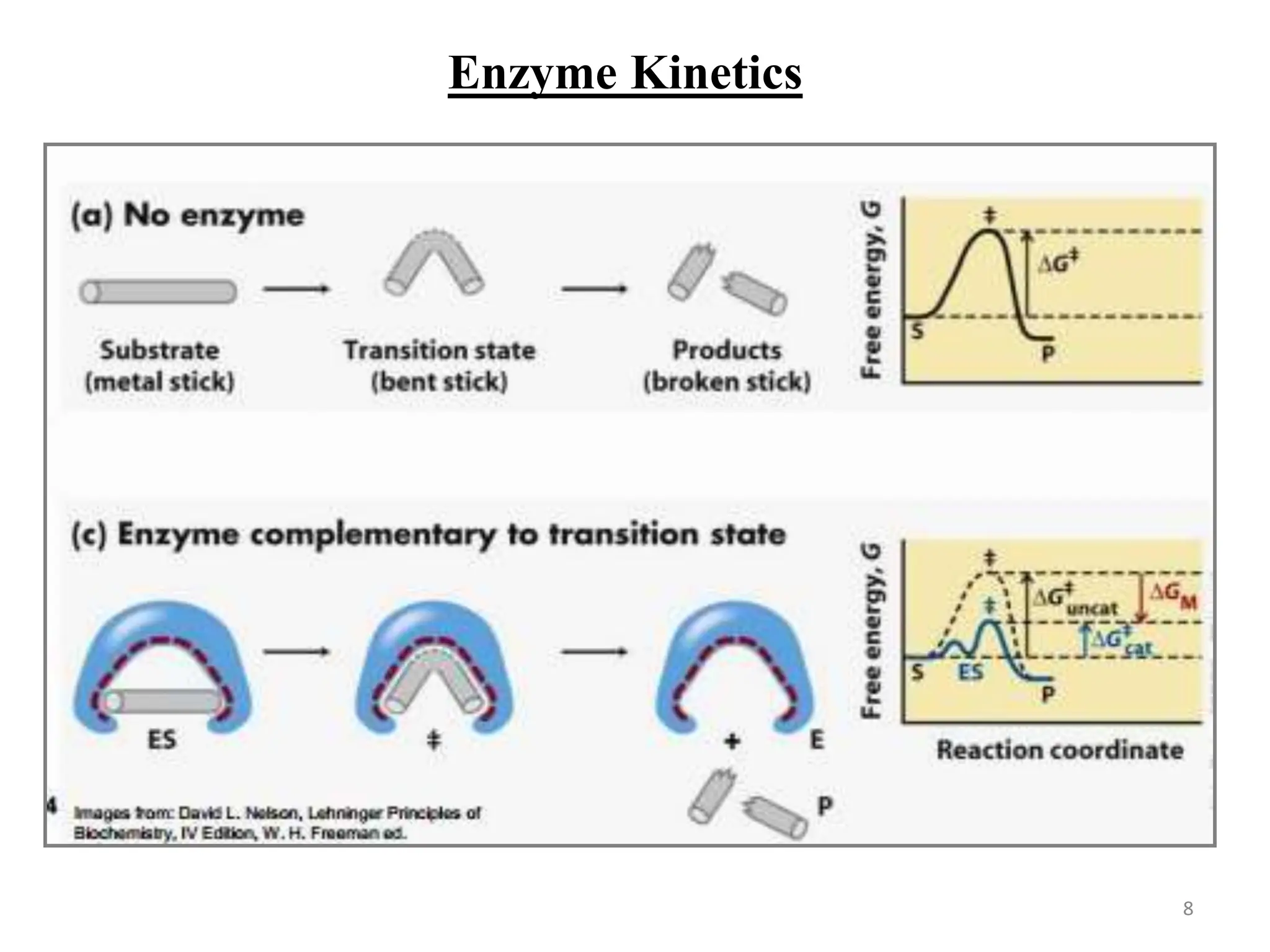

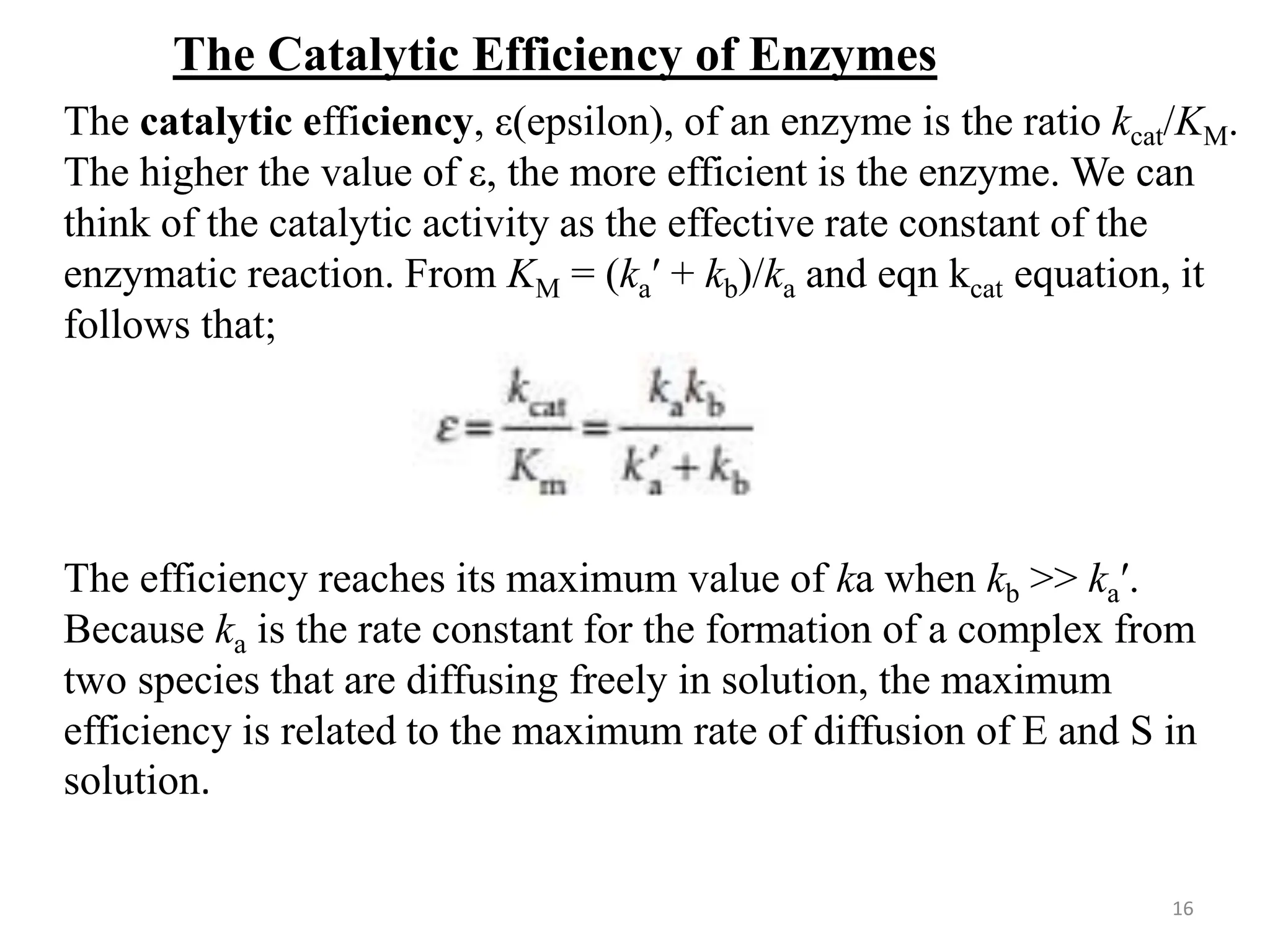

The document discusses enzyme catalysis, highlighting enzymes as biological catalysts with active sites that bind substrates and convert them into products. It elaborates on models that describe substrate binding, such as the lock-and-key and induced fit models, and explains the Michaelis-Menten mechanism for enzyme kinetics. Additionally, it covers the significance of the Michaelis constant (km) and catalytic efficiency (ε), detailing how they relate to enzyme activity and efficiency.

![9

The Michaelis–Menten Mechanism of Enzyme Catalysis

The principal features of many enzyme-catalysed reactions are as

follows:

I. For a given initial concentration of substrate, [S]0, the initial

rate of product formation is proportional to the total

concentration of enzyme, [E]0.

II. For a given [E]0 and low values of [S]0, the rate of product

formation is proportional to [S]0.

III. For a given [E]0 and high values of [S]0, the rate of product

formation becomes independent of [S]0, reaching a maximum

value known as the maximum velocity, vmax](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-9-2048.jpg)

![11

The Michaelis–Menten Mechanism of Enzyme Catalysis

Derivation of Equation:

The rate of product formation according to the Michaelis–Menten

mechanism is:

The concentration of the enzyme–substrate complex is obtained by

invoking the steady-state approximation and writing;

Simplifies to:

where [E] and [S] are the concentrations of free enzyme and

substrate, respectively. Now the Michaelis constant can be defined

as:

KM has the same units as molar concentration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-11-2048.jpg)

![12

The Michaelis–Menten Mechanism of Enzyme Catalysis

To express the rate law in terms of the concentrations of enzyme and

substrate added, we note that: [E]0 =[E] + [ES].

In addition, because the substrate is typically in large excess relative

to the enzyme, the free substrate concentration is approximately equal

to the initial substrate concentration and we can write [S] ≈ [S]0. It

then follows that;

The Michaelis-Menten equation is then obtained by substituting [ES]

is the rate

The Michaelis–Menten Equation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-12-2048.jpg)

![13

Significance of Michaelis–Menten constant, Km

Experimental observation show that:

I. When [S]0 << KM, the rate is proportional to [S]0

II. When [S]0 >> KM, the rate reaches its maximum value and is

independent of [S]0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-13-2048.jpg)

![17

Determining the Catalytic Efficiency of an Enzyme

The enzyme carbonic anhydrase catalyses the hydration of CO2

in red blood cells to give bicarbonate (hydrogen carbonate) ion:

CO2(g) + H2O(l) → HCO3−

(aq) + H+

(aq)

The following data were obtained for the reaction at pH = 7.1,

273.5 K, and an enzyme concentration of 2.3 nmol dm−3

[CO2

]/(mmol dm3

) rate/(mmol dm3

s1

)

1.25 0.0278

2.5 0.05

5 0.0833

20 0.167

Atkins, Physical Chemistry , 8th Ed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-17-2048.jpg)

![18

Determining the Catalytic Efficiency of an Enzyme

Solution:

Draw a straight line graph to determine KM and Vmax.

[CO2

]/(mmol dm3

) rate/(mmol dm3

s1

) 1/(rate/(mmol dm3

s1

)

1/[CO2

]/(mmol dm3

)

1.25 0.0278 36.0 0.8

2.5 0.05 20.0 0.4

5 0.0833 12.0 0.2

20 0.167 6.0 0.05

Atkins, Physical Chemistry , 8th Ed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-18-2048.jpg)

![19

Determining the Catalytic Efficiency of an Enzyme...

y = 39.97x + 4.002

R² = 1

0.0

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

35.0

40.0

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

1/(v/mmol/dm

3

s

1

)

1/(mmol/dm3 [CO2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enzymecatalysis-240725102051-ab11d80a/75/Enzyme-Catalysis-Heterogeneous-and-Homogeneous-19-2048.jpg)