This document discusses enterocutaneous fistulas, including:

1. Fistulas are abnormal connections between two epithelial surfaces, most commonly occurring after abdominal surgery as a complication.

2. Classification systems include etiologic (cause), anatomic (location), and physiologic (output amount) which provide understanding for management.

3. Prevention focuses on proper preoperative patient preparation and surgical technique to reduce postoperative fistula risks.

![Introduction

Fistula is derived from Latin word that means “PIPE”.

A Fistula is an abnormal connection between two epithelised surfaces.

Fistulas that involve Gut and Skin are called ENTEROCUTANEOUS

FISTULA.

Most GI Fistula (75 % - 85 %) occur as a complication of abdominal

surgery . However 15 – 25 % of fistula evolve spontaneously [1].

1. www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/intestinalfistula](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-2-2048.jpg)

![Introduction

Even with recent advances in management & critical care

enterocutaneous fistulas remain great challenges to the

surgeon.

Mortality remains high, between 10–30% in recent series,

largely due to the frequent complications of sepsis and

malnutrition.[1]

1.Ann Surg 1960;152:445](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-3-2048.jpg)

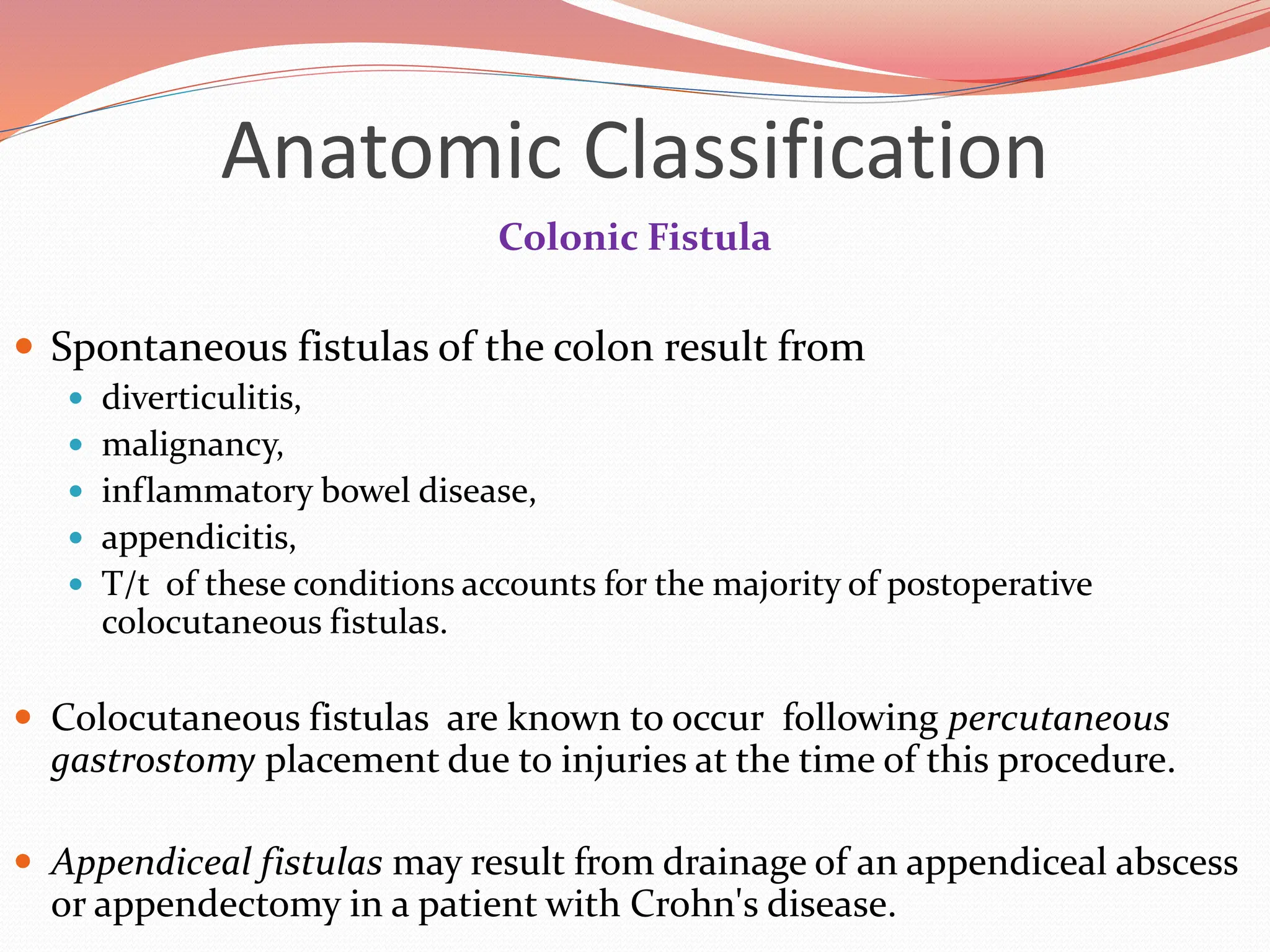

![Anatomic Classification

Gastric Fistulas

The most common cause gastrocutaneous fistula formation is the

removal of a gastrostomy feeding tube.

Nearly 90% of patients develop fistula when the tube had been in situ

for more than 9 months.

There are numerous reports of resolution of these fistulas with fibrin-

glue injection rather than operative closure.

The rate of gastrocutaneous fistula following operations for

nonmalignant processes such as ulcer disease, reflux disease, and obesity

is between 0.5% and 3.9%.

Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:296 [PubMed: 14745411]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-12-2048.jpg)

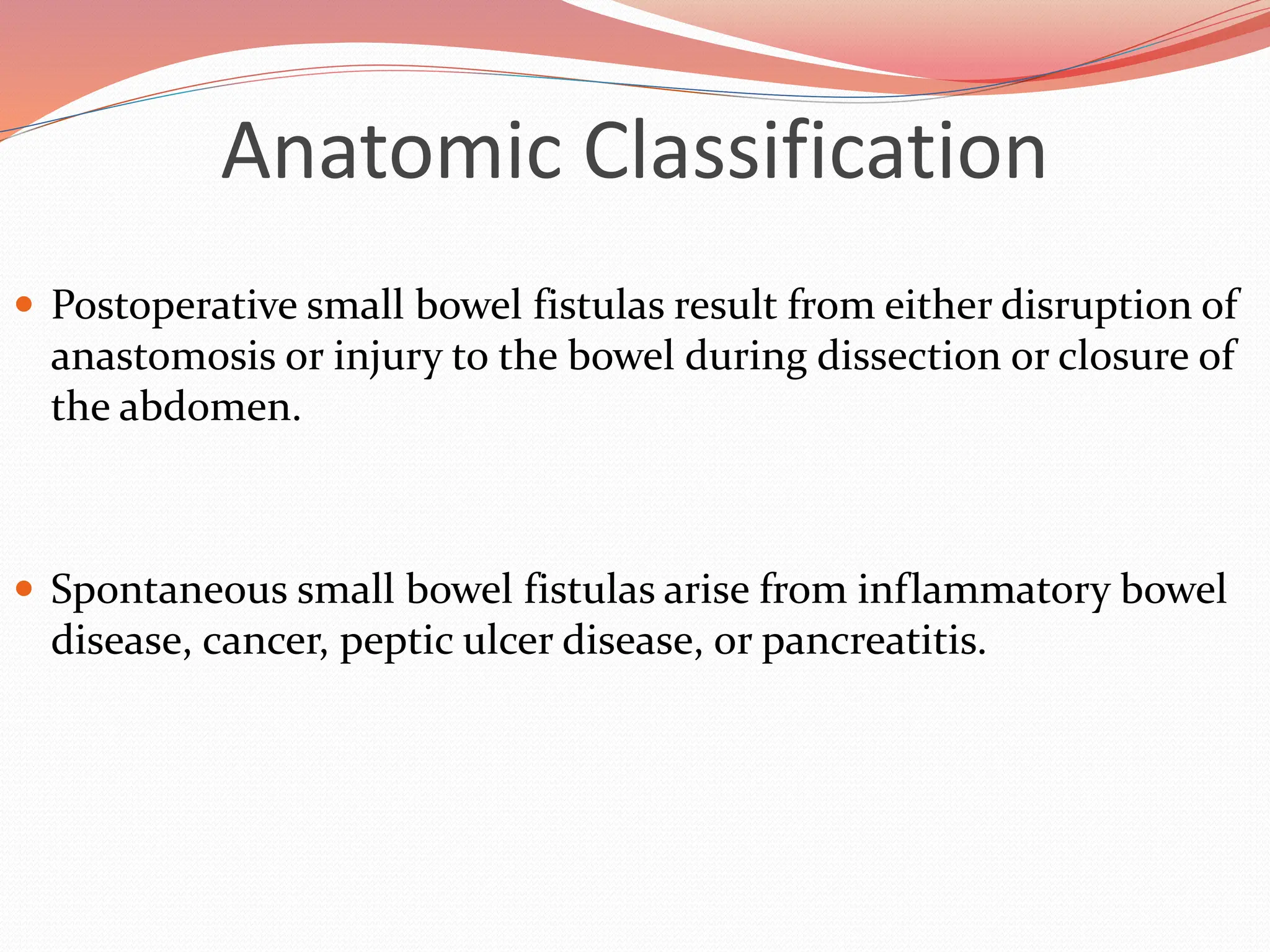

![Anatomic Classification

Edmunds and associates reported a decreased spontaneous

closure rate with lateral duodenal fistulas when compared to

duodenal stump fistulas.[1]

Small Bowel Fistulas

The majority of gastrointestinal cutaneous fistulas arise from the

small intestine.

Seventy to ninety percent of enterocutaneous fistulas occur in

postoperative period.

1.theAnn Surg 1960;152:445 [PubMed: 13725742]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-14-2048.jpg)

![Physiologic Classification

Enterocutaneous fistulas cause

the loss of fluid,

minerals,

trace elements,

and protein,

allow the release of irritating and caustic substances onto the skin.

Accurate measurement of both the amount and nature of enterocutaneous effluent

allows for accurate replacement.

Fistulas may be divided into 3 types :-

high-output (>500 mL per day),

moderate-output (200–500 mL/day),

low-output (<200 mL/day) groups.

Classification of enterocutaneous fistulas by the amount of daily output provides

information regarding mortality and in recent series may predict spontaneous

closure.[1,2]

1.British J Surg 1989;76:676 [PubMed: 2504436]

2.J Am Coll Surg 1999;188:483 [PubMed: 10235575]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-19-2048.jpg)

![Physiologic Classification

More recently, Levy and colleagues reported

50% mortality rate in patients with high-output fistulas

26% mortality with low-output fistulas

Campos and associates suggested that patients with low-output

fistulas were three times more likely to achieve closure without

operative intervention.

The reason for these different rates of closure is that,

high-output fistulas are likely to be of small-bowel origin,

low-output fistulas are likely to be of colonic origin [1].

1.Br J Surg 1989;76:676 [PubMed: 2504436]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-20-2048.jpg)

![Prevention

Mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation reduce the amount

of particulate fecal material as well as colonic bacterial counts and

thus decrease the risk of fistula formation.

A recent meta-analysis of studies examining mechanical and

antibiotic bowel preparation suggests that bowel prep, may

increase the risk of anastomotic leakage, but confirmatory studies

are required before omission of preparation would be recommended

in practice.[1]

1.Slin K, Vicaut E, Panis Y et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of colorectal surgery with or without

mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg 2004;91:1125](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-27-2048.jpg)

![Pathophysiology

The presence of infection adds to the stress on these patients and

limits the ability to achieve positive nitrogen balance.

Series of Hill and colleagues suggest that, until sepsis is

controlled, it is almost impossible to put patients into positive

nitrogen balance, even with any level of nutritional support.[1]

World J Surg 1988;12:191 [PubMed: 3134764]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-33-2048.jpg)

![Identification and Resuscitation

The diagnosis is now

clear [enterocutaneus

fistula ] and

management shifts

from routine

postoperative care to

the management of a

potentially critically ill

patient.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-39-2048.jpg)

![Phase 1: Recognition and Stabilization

In a study of 100 patients with fistulizing Crohn's disease,

infliximab infusion resulted in complete response in 50 patients,

partial response in 22 patients, and no response in 28 patients.[1]

Whether this agent will be of use in patients without Crohn's

disease or ulcerative colitis remains to be determined

1.Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:722 [PubMed: 11280541]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-51-2048.jpg)

![Phase 3: Decision

The timing of operative intervention for fistulas that are unlikely

to or fail to close is important.

Early operation is indicated to control sepsis not amenable to

percutaneous intervention.

First, 90–95% of fistulas that will spontaneous close typically do

so within 5 weeks of the original operation.

Furthermore, operation during the first 10 days to 6 weeks from

diagnosis of postoperative fistulas is made more difficult by the

"obliterative peritonitis" described by Fazio and associates.[1]

1.World J Surg 1983;7:481 [PubMed: 6624123]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enterocutaneousfistulla28-240222172004-b22a3bf0/75/Enterocutaneous-Fistula-general-surg-pptx-63-2048.jpg)