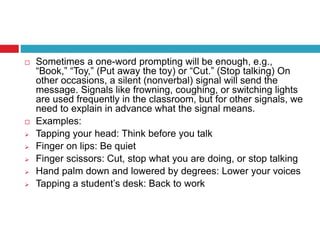

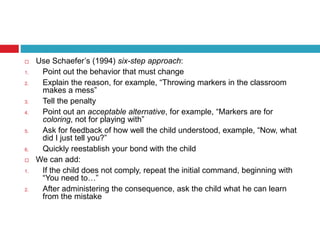

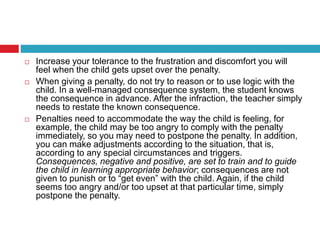

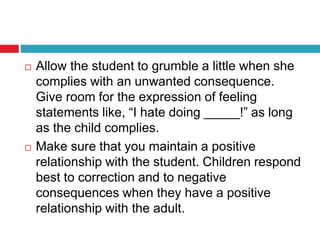

The document provides guidelines for establishing and enforcing classroom rules and consequences. It recommends that teachers involve students in creating a small number of specific, observable, and positively stated rules. Rules should be reviewed regularly and enforced consistently with prompts, warnings, and proportional consequences like time-outs. Both compliance and non-compliance should immediately result in positive or negative responses respectively to reinforce the connection between behaviors and outcomes for students.