The document discusses current practices and future directions for encouraging digital writing equity in pre-K-12 classrooms. It highlights various research topics, including the integration of technology and multimedia in writing instruction, and emphasizes the need for educators to recognize students' out-of-school experiences as valuable resources for learning. The document also outlines specific research findings related to technology use in literacy education and the implications for instructional practices in diverse learning environments.

![Findings

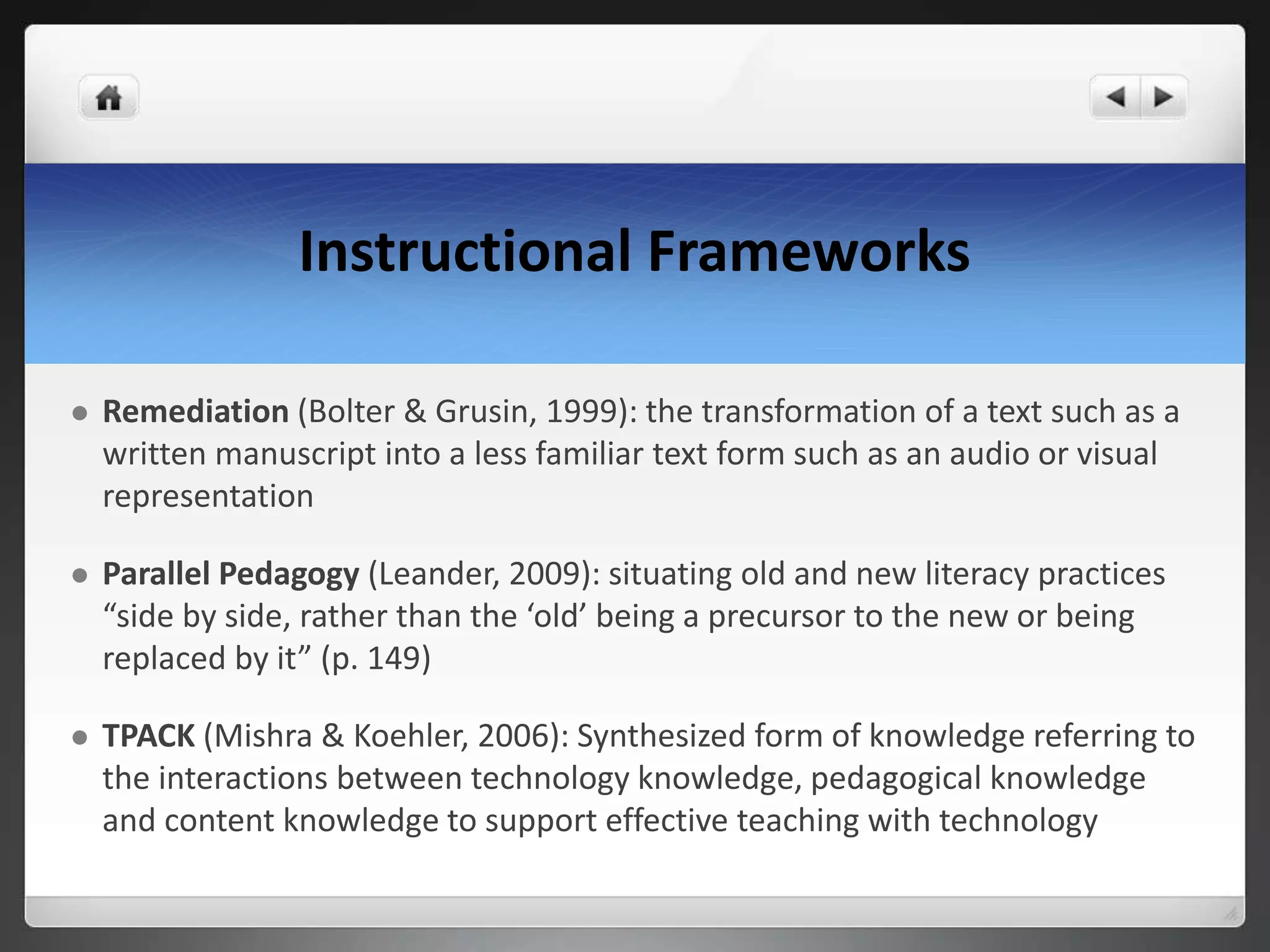

Written Language:

100% of multimodal compositions included written language

Participants recognized the limited space in (free) digital tools and reflected on the

brevity and clarity of their messages, connecting what they learned to their

writing instruction:

“Words, when used, must be used sparingly. While this does not seem like it would be a problem in the

classroom [because] most kids try to write as little as possible, being concise is not the same as using a

few words. So writers must not only learn to cut out the extra, they must also be sure to leave in the

necessary words so that their meaning is clearly conveyed.” – Opal, 6th grade ELA teacher

Technical challenges affected use of written language

The majority of participants reflected on the motivation and interest to use modes

other than written language given the affordances of the digital tools.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalwriting-lra2015-151202081722-lva1-app6892/75/Encouraging-Digital-Writing-Equity-in-Pre-K-12-Classrooms-Current-Practices-and-Future-Directions-86-2048.jpg)