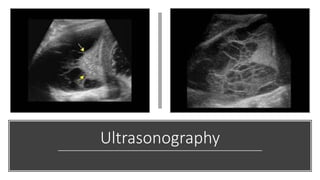

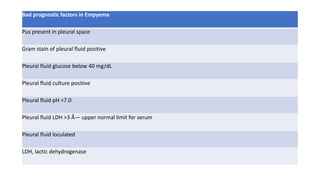

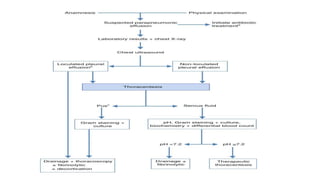

Bacterial pneumonia can result in parapneumonic effusions or empyema in the pleural space in about 40% of hospitalized cases. Empyema is defined as pus in the pleural space. Effusions are classified into exudative, fibropurulent, and organized stages. Common bacteria include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and various gram-negative rods. Diagnosis involves chest imaging, microbiology of pleural fluid, and biochemistry of the fluid. Treatment involves antibiotics, tube thoracostomy, possible intrapleural fibrinolytics or antibiotics, and potentially more invasive procedures like thoracoscopy or thoracotomy if the effusion becomes complicated or organized