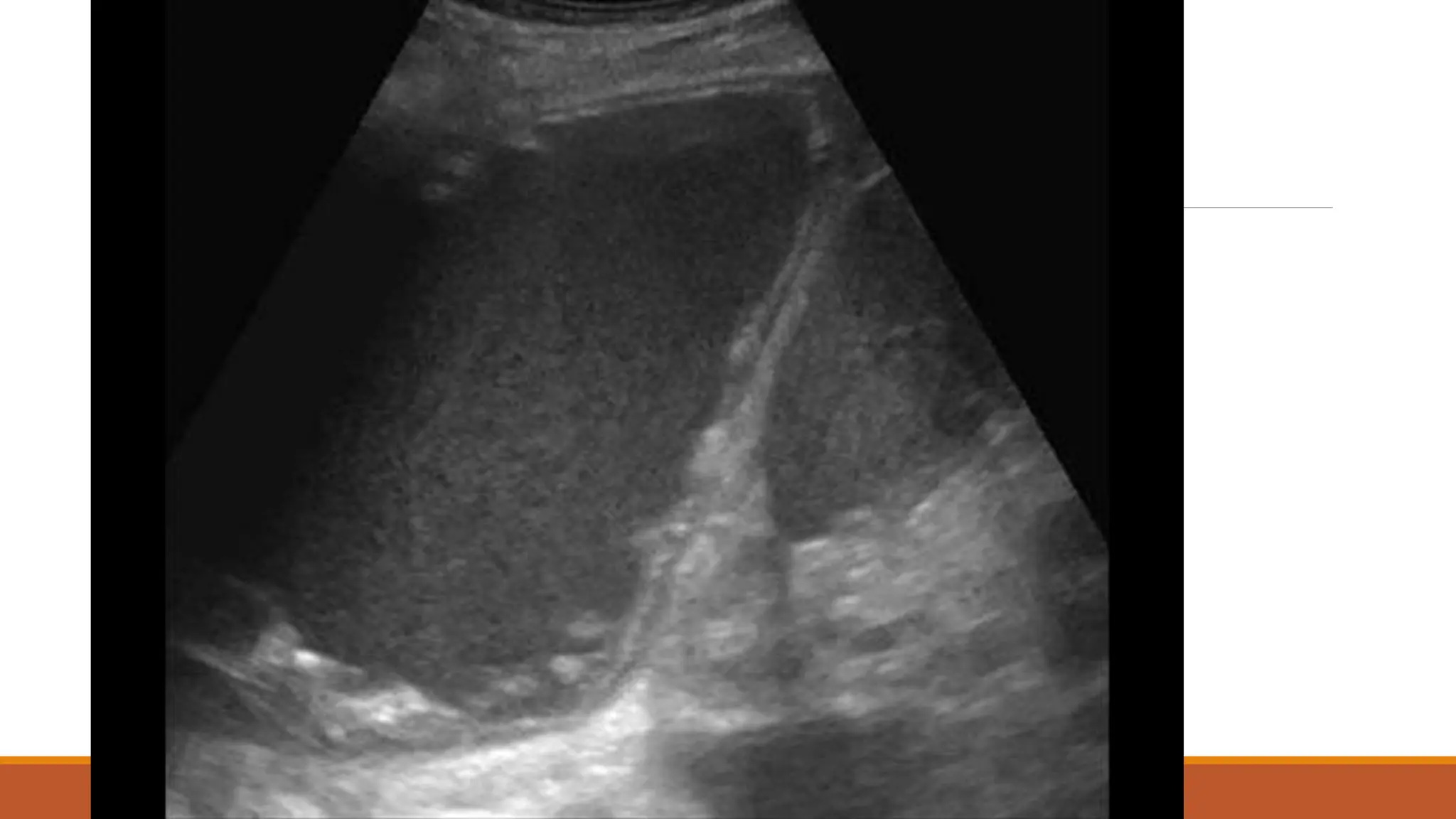

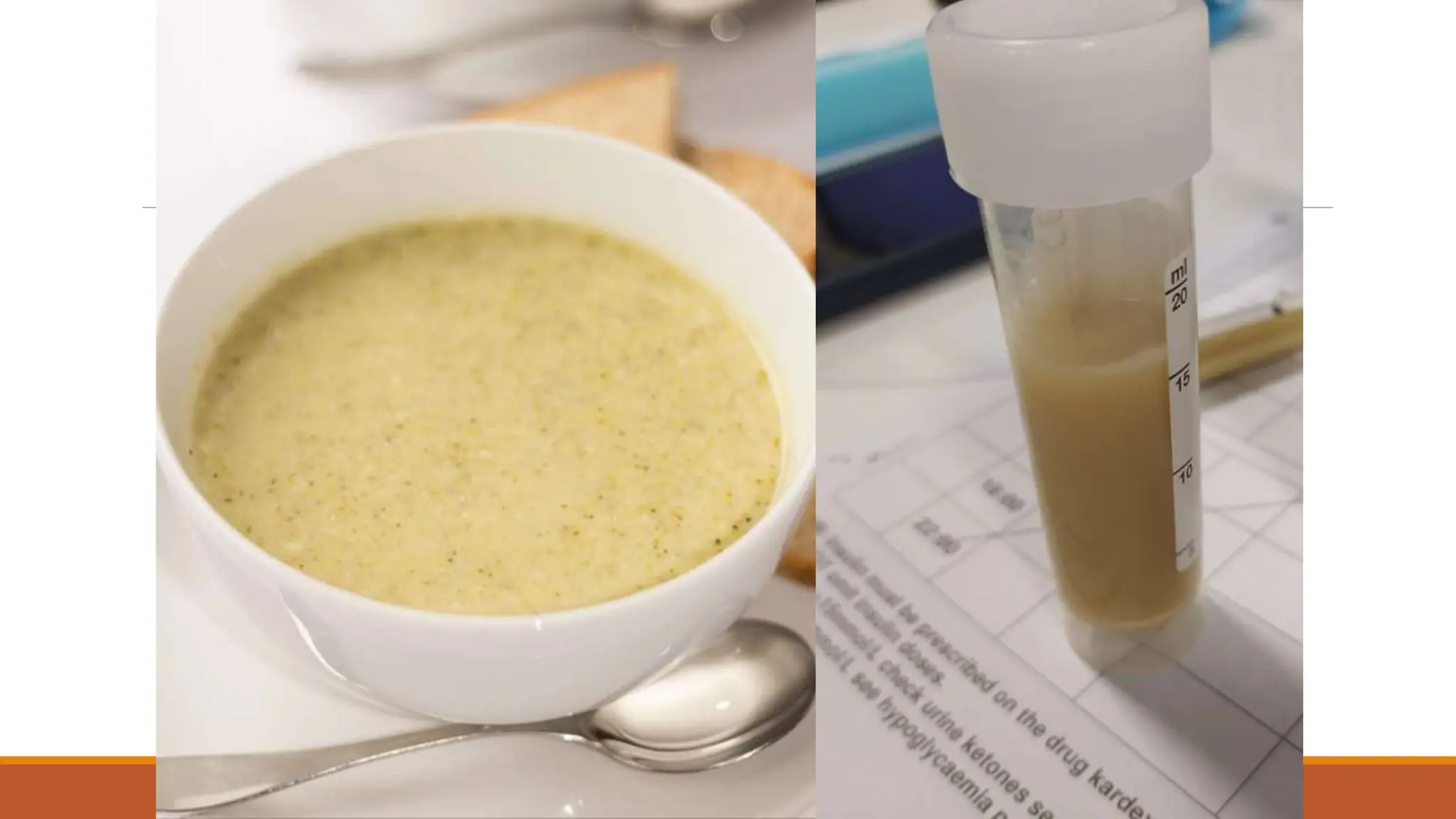

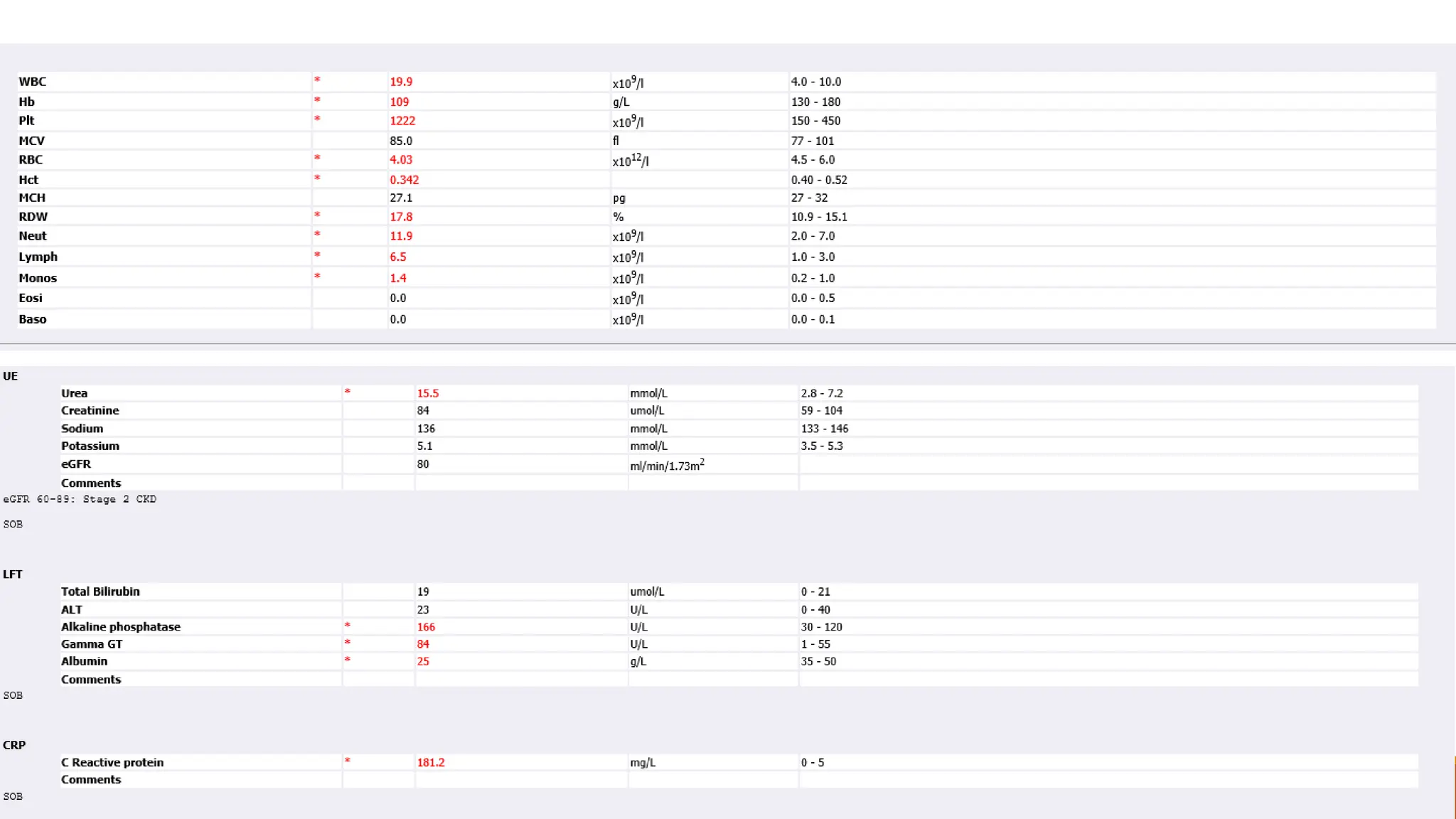

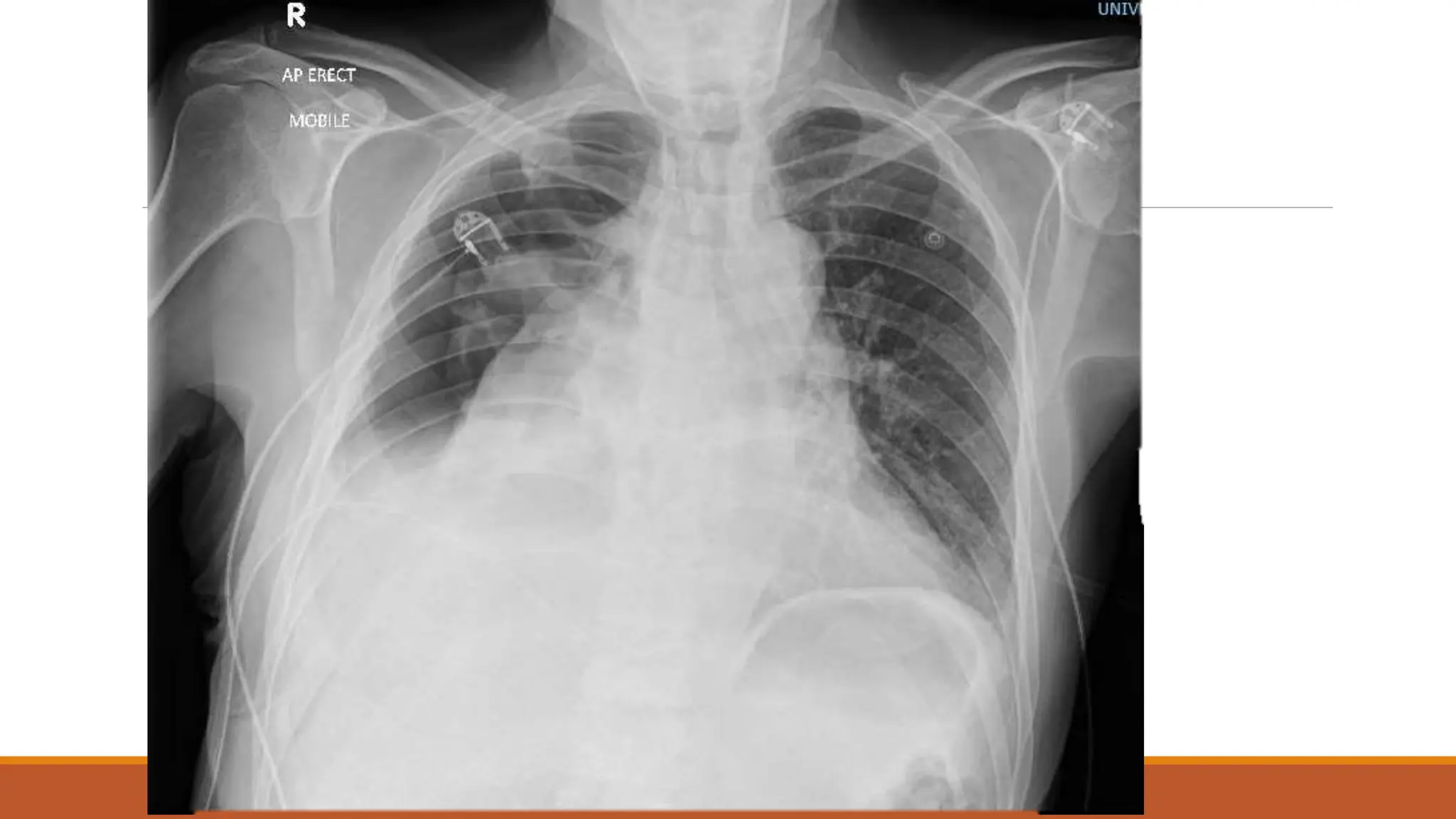

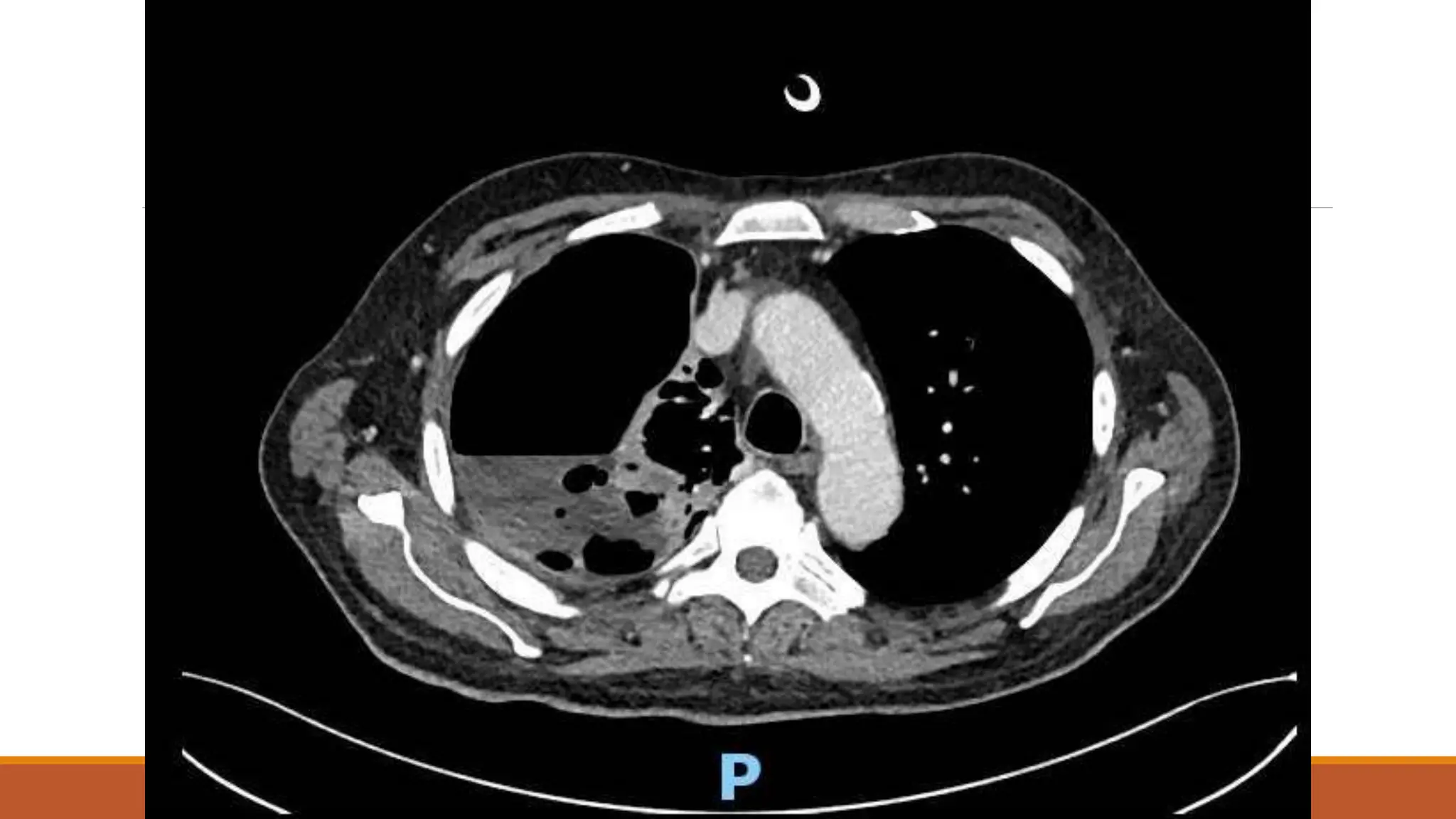

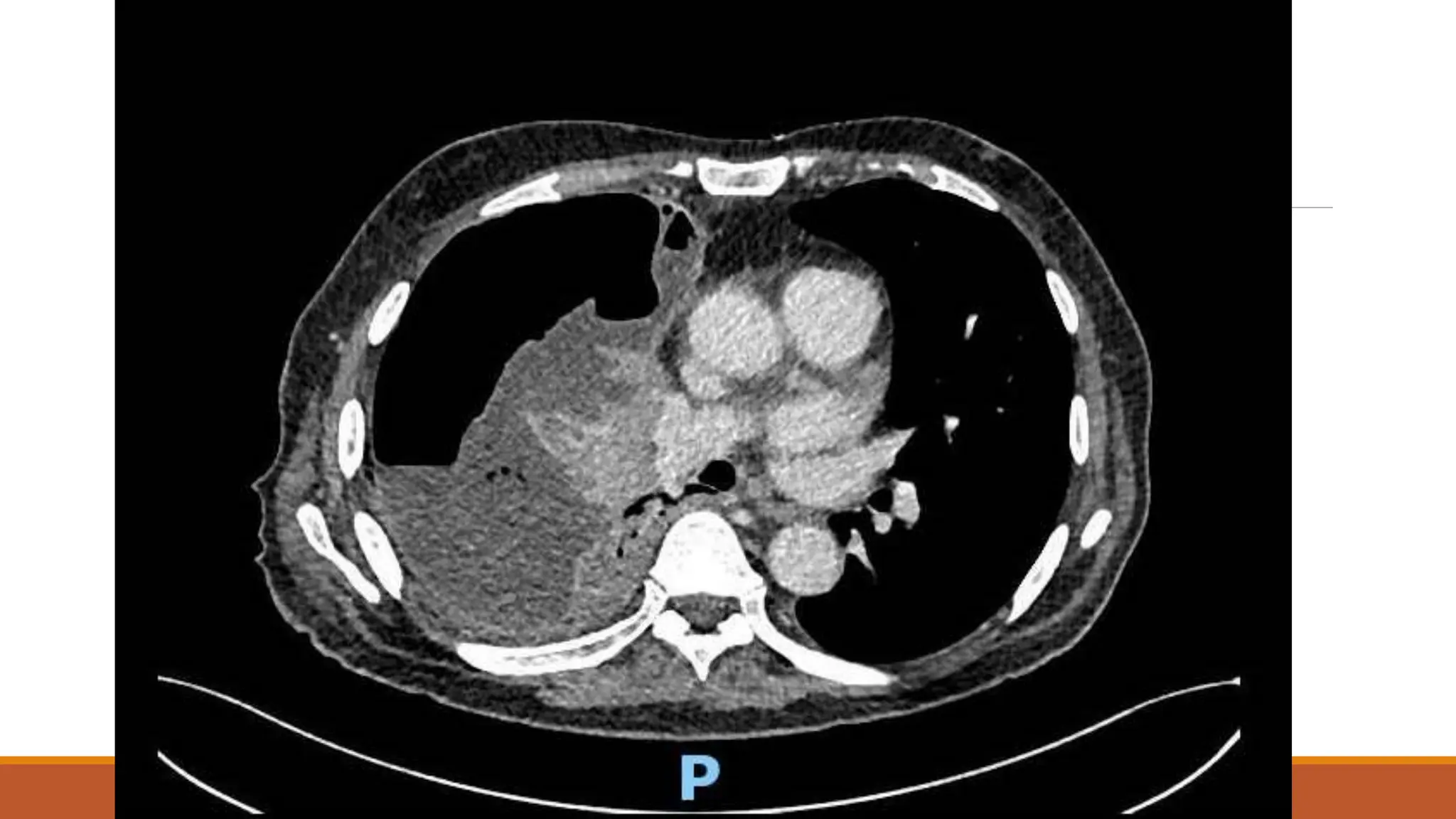

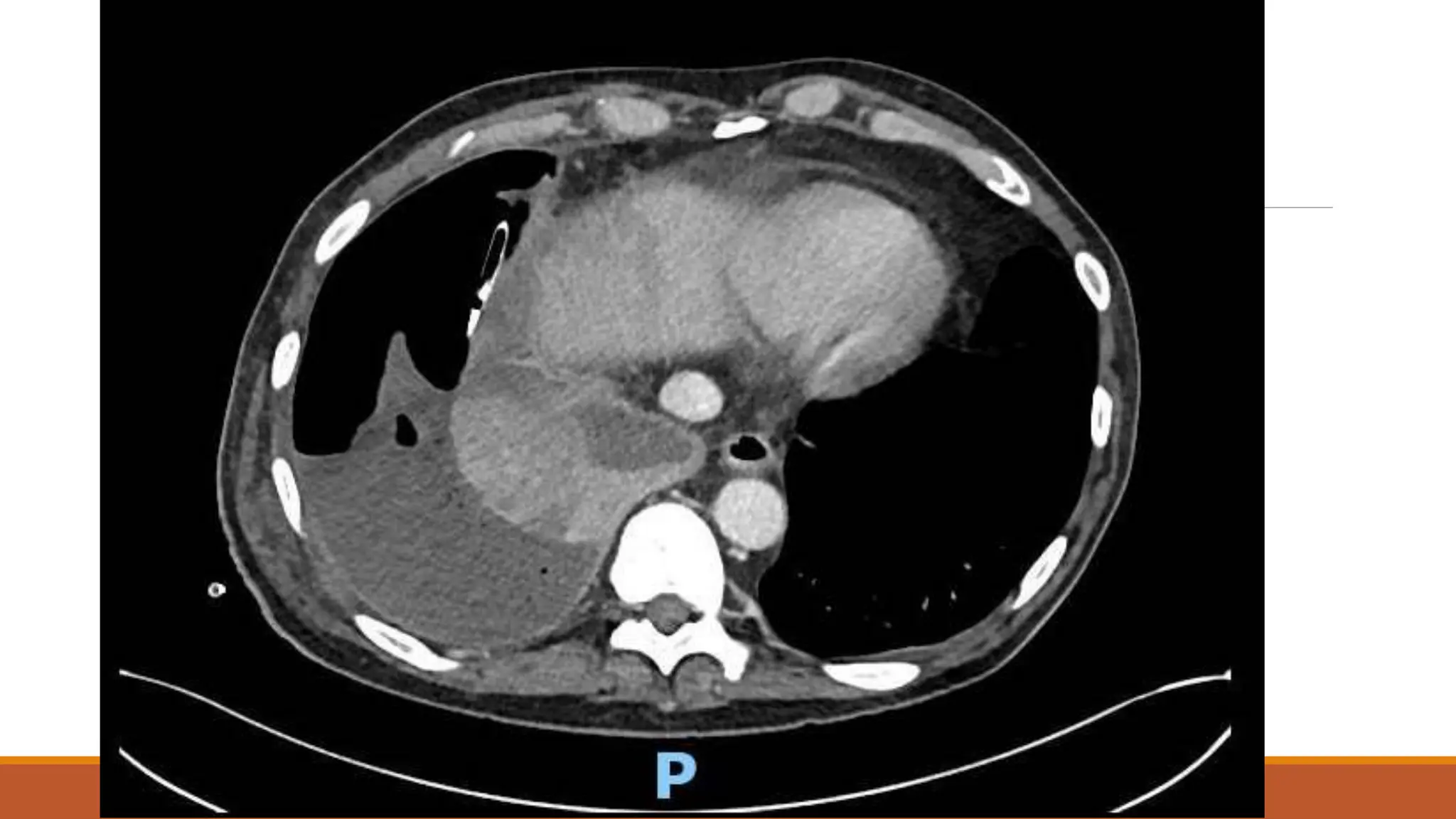

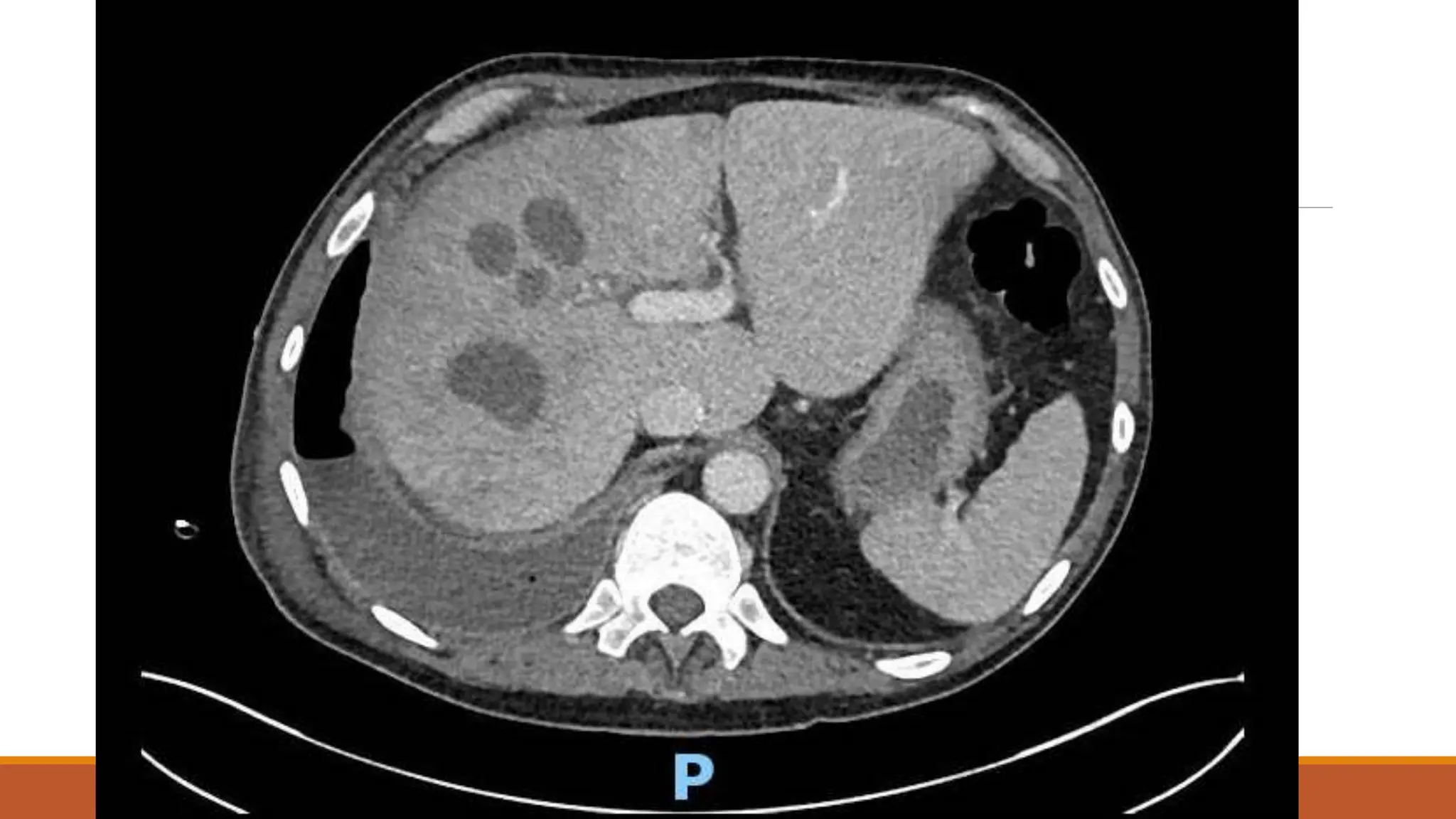

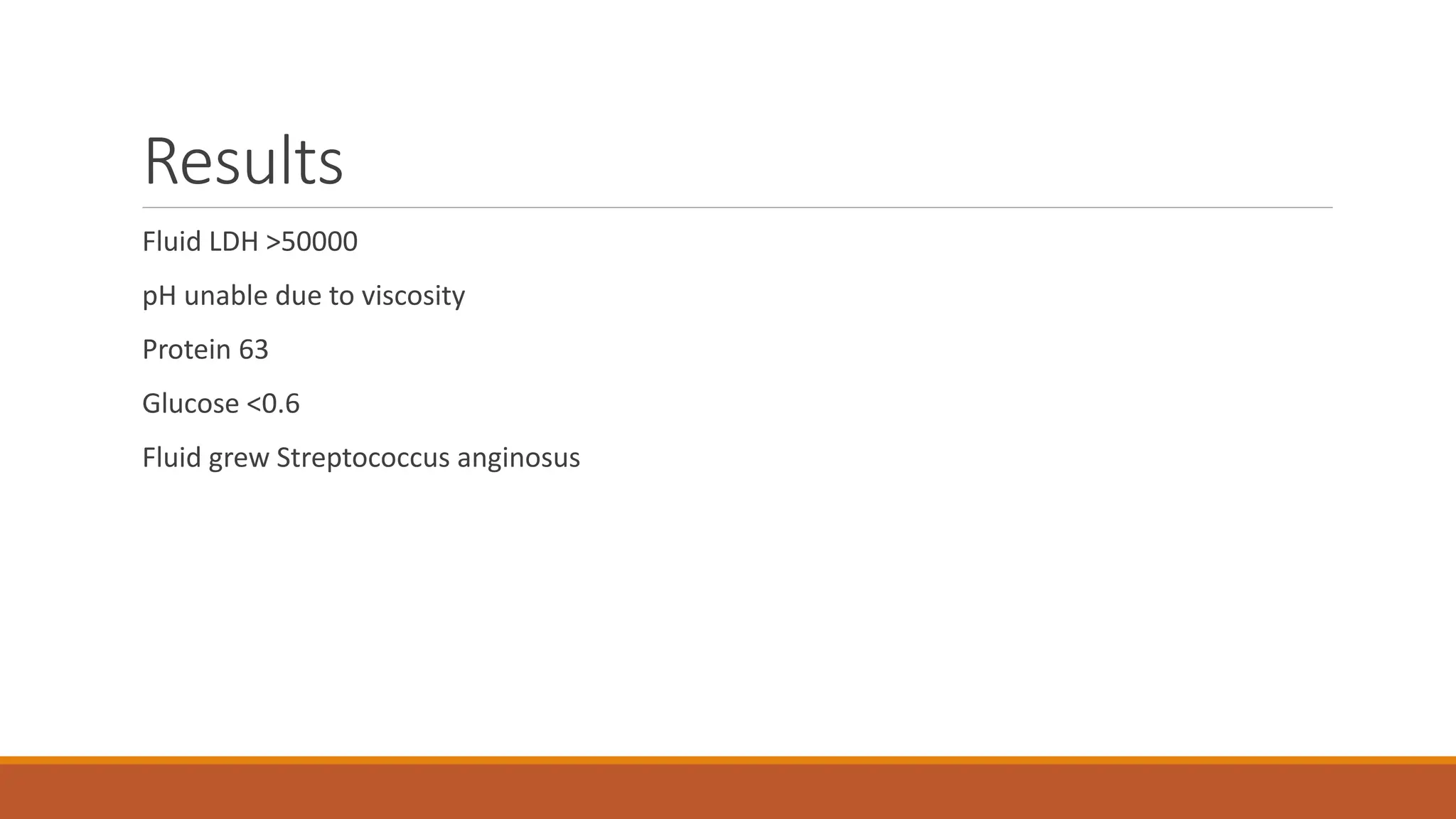

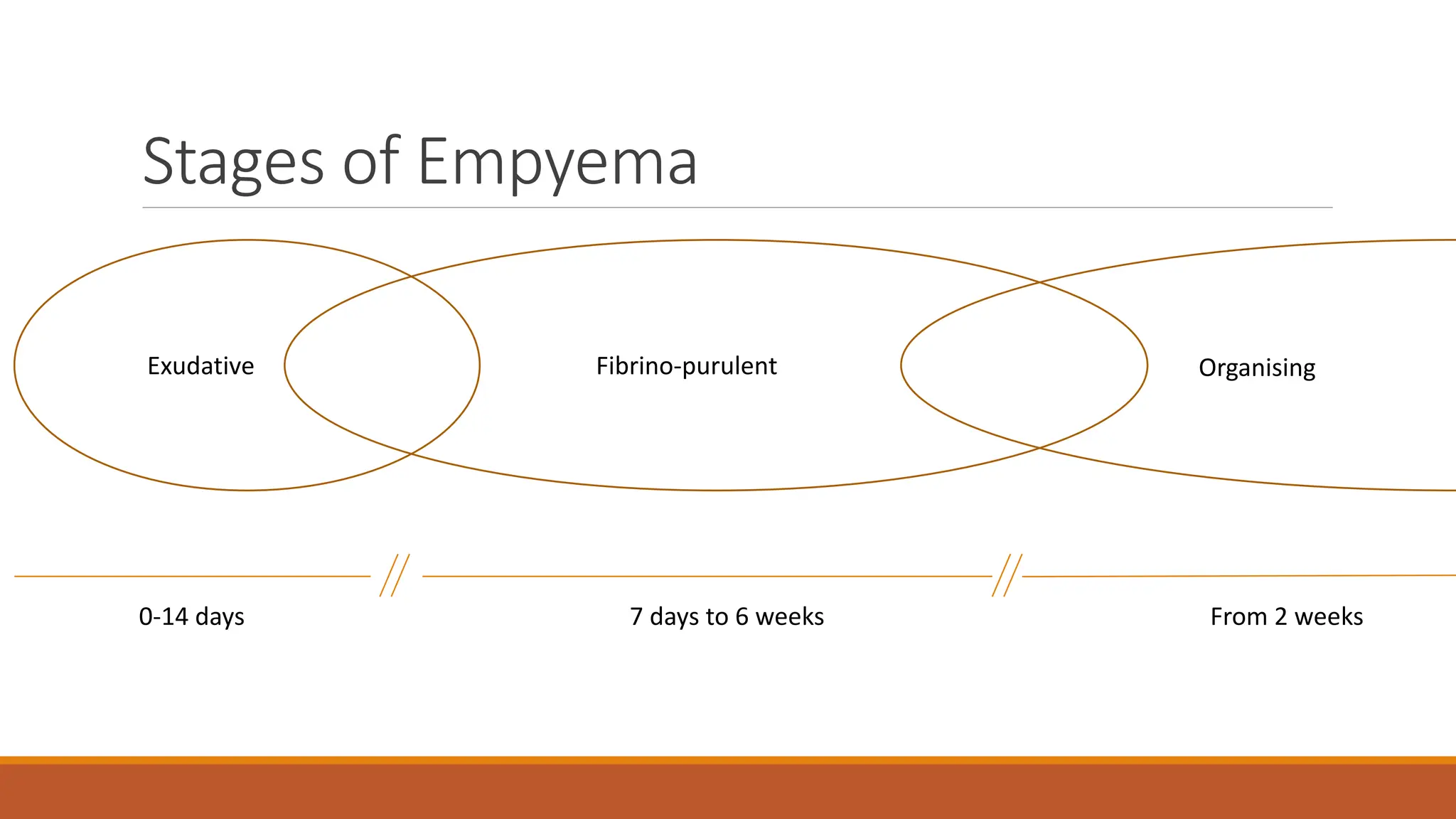

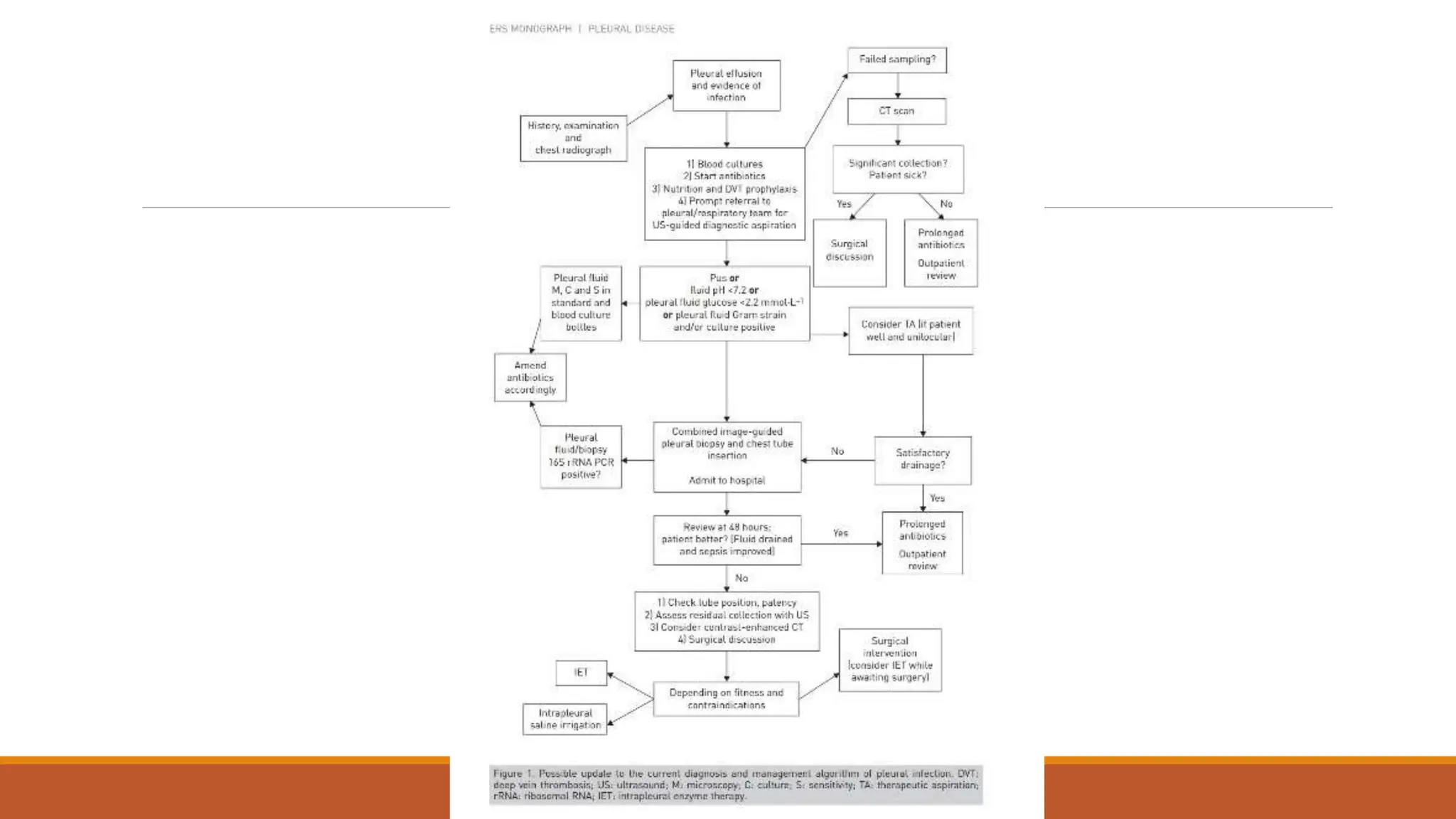

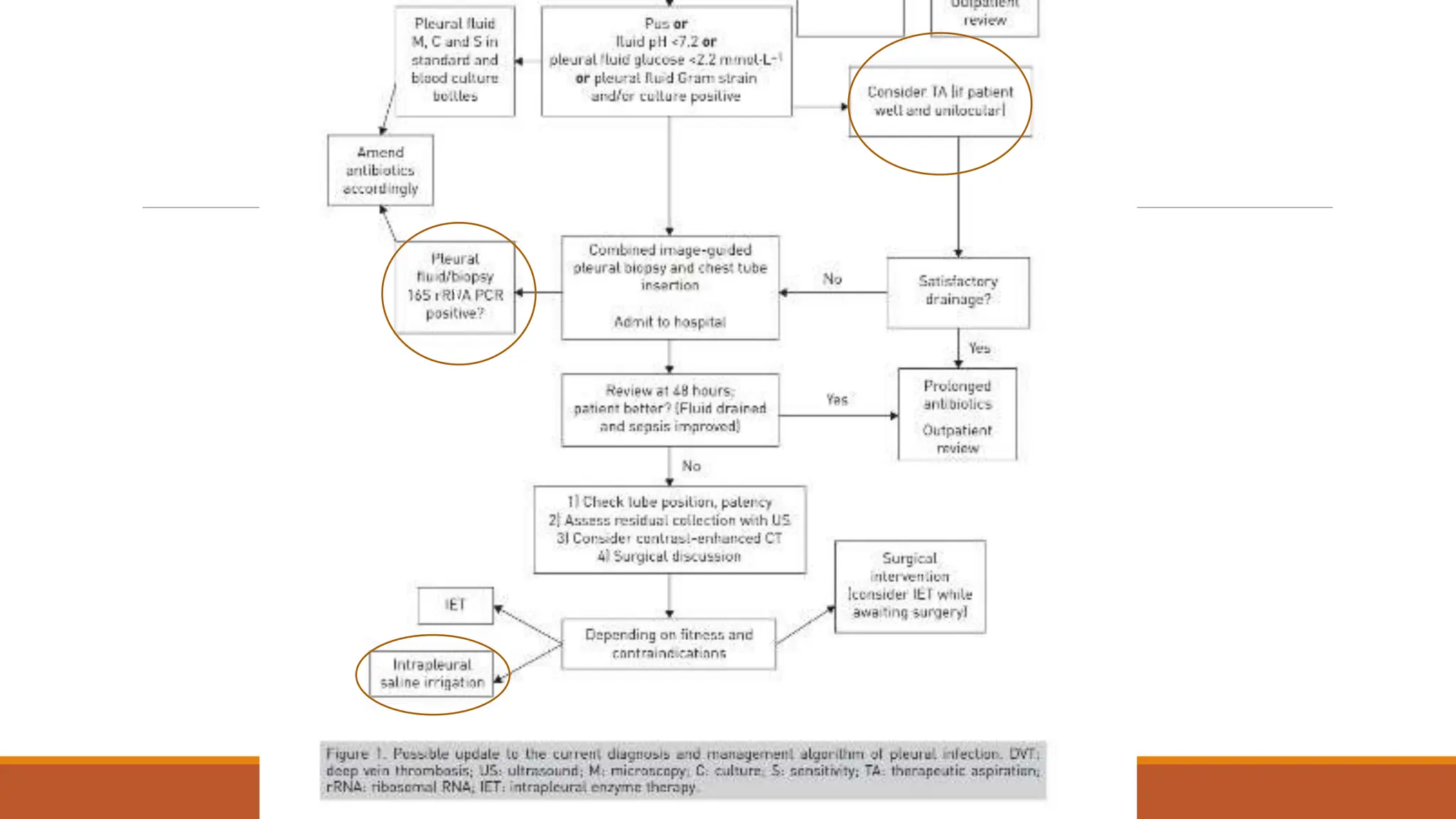

The document discusses a case of empyema in a 63-year-old male who experienced worsening respiratory symptoms and significant health decline after a pneumonia diagnosis. It provides an overview of pleural infections, detailing the rising incidence, distinct microbiological patterns, clinical presentation, and stages of empyema, alongside treatment challenges and recent clinical trial results. Additionally, it outlines future research directions and potential advancements in the management of pleural infections.