The document provides an overview of basic astronomical calculations related to gravity and motion, presented by Sukalyan Bachhar, a senior curator at the National Museum of Science & Technology in Bangladesh. It covers various measurement systems for angles, definitions of trigonometric ratios, the laws of motion, and fundamental concepts in physics such as Newton's law of gravitation and the properties of light. Additionally, it includes mathematical equations and relationships essential for understanding motion and gravitational forces.

![1

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Gravity and motion ( Lecture – 1)

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-1-320.jpg)

![2

Basic facts: Measurements of angles:

• There are mainly three measurement systems for angles.

• (1) Degree system ; (2) Grade system & (3) Radian system.

• #(1) Degree system: One right angle = 900 .

– Meaning of superscript: ‘0’ Degree; ‘’ Minute & ‘’ Seconds.

– This system of measurement is popular one in engineering field.

• # (2) Grade system: One right angle = 100g .

– Meaning of superscript: ‘g’ Grade; ‘’ Minute & ‘’ Seconds.

– This system of measurement is suitable for calculating as it is based on 100

instead of degree system which is based on 60.

• # (3) Radian system: One right angle = c/2

Meaning of superscript: ‘c’ Radian [ ‘c’ comes from circle].

– This system of measurement is the most close to nature (related to circle)

and widely used in pure science.

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-2-320.jpg)

![3

Basic facts: Concept about radian

• Definition of one radian: One radian is an angle subtended at centre by the arc of a circle whose length is

equal to the radius of the circle.

• Definition of (pi) : It is experimentally established that the ratio of circumference (or perimeter) of a

circle to its diameter is always constant.

This constant is known as .

• Actual value of is still undiscovered, it is used as:

3.1415926535897932384626433832795 ; but as rough estimate, 22/7.

• Circumference of a circle:

From the above definition: Circumference/Diameter = C/D =

But, diameter = 2 Radius. So, C/2r = C = 2r.

• i.e, C = 2r

[N.B. : Where ‘C’ ‘D’ and ‘r’ stand for circumference, diameter and radius

of a circle respectively.]

• It is clear that: in case of subtending an angle at centre by the arc of any

circle, the angle subtended at centre is directly proportional to its arc length..

• Now, from definition of one radian: Angle (in radian) = arc length/radius.

= s/r s = r.

[N.B. : Where ‘’ ‘s’ and ‘r’ stand for angle, arc length and radius of a circle respectively.]

• That is: one complete angle = Circumference/radius = 2r/r = 2. So, 2c = 3600 90 0 = c/2

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-3-320.jpg)

![28

Gravitational acceleration on the planets

Acceleration Due to Gravity Comparison

Body Mass Ratio Radius Ratio

g / g-Earth

Acceleration Due

to Gravity, "g" [m/s²]

Acceleratio

n Due

to Gravity,

"g" [m/s²]

Sun 3327760 109.091 27.95 274.13

Mercury 0.0553 0.383 0.37 3.59

Venus 0.815 0.949 0.90 8.87

Earth 1.000 1.000 1.00 9.81

Moon 0.0123 0.273 0.17 1.62

Mars 0.107 0.533 0.38 3.77

Jupiter 317.8 11.200 2.65 25.95

Saturn 95.2 9.450 1.13 11.08

Uranus 14.5 4.010 1.09 10.67

Neptune 17.1 3.880 1.43 14.07

Pluto 0.0021 0.187 0.04 0.42

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-28-320.jpg)

![35

Escape velocity from solar system

Location with respect to Ve

[2] Location with respect to Ve

[2]

on the Sun, the Sun's gravity: 617.5 km/s

on Mercury, Mercury's gravity: 4.3 km/s at Mercury, the Sun's gravity: 67.7 km/s

on Venus, Venus' gravity: 10.3 km/s at Venus, the Sun's gravity: 49.5 km/s

on Earth, the Earth's gravity: 11.2 km/s at the Earth/Moon, the Sun's gravity: 42.1 km/s

on the Moon,

the Moon's

gravity:

2.4 km/s at the Moon, the Earth's gravity: 1.4 km/s

on Mars, Mars' gravity: 5.0 km/s at Mars, the Sun's gravity: 34.1 km/s

on Jupiter, Jupiter's gravity: 59.5 km/s at Jupiter, the Sun's gravity: 18.5 km/s

on Saturn, Saturn's gravity: 35.6 km/s at Saturn, the Sun's gravity: 13.6 km/s

on Uranus, Uranus' gravity: 21.2 km/s at Uranus, the Sun's gravity: 9.6 km/s

on Neptune, Neptune's gravity: 23.6 km/s at Neptune, the Sun's gravity: 7.7 km/s

in the solar

system,

the Milky Way's

gravity:

≥ 525 km/s[3]

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-35-320.jpg)

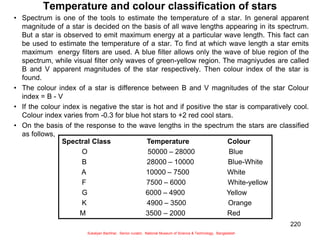

![56

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Earth and Motion ( Lecture – 2)

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-56-320.jpg)

![57

Energy released by an asteroid on the collision course

with the Earth

*

*Main asteroid belt

Main article: Asteroid belt

The majority of known asteroids orbit within the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Marsand Jupiter,

generally in relatively low-eccentricity (i.e., not very elongated) orbits. This belt is now estimated to contain

between 1.1 and 1.9 million asteroids larger than 1 km (0.6 mi) in diameter,[29] and millions of smaller

ones.[30] These asteroids may be remnants of theprotoplanetary disk, and in this region

the accretion of planetesimals into planets during the formative period of the solar system was prevented by

large gravitational perturbations byJupiter.

[edit]Trojans

Main article: Trojan asteroids

Trojan asteroids are a population that share an orbit with a larger planet or moon, but do not collide with it

because they orbit in one of the two Lagrangian points of stability, L4 and L5, which lie 60° ahead of and

behind the larger body.

The most significant population of Trojan asteroids are the Jupiter Trojans. Although fewer Jupiter Trojans

have been discovered as of 2010, it is thought that there are as many as there are asteroids in the main

belt.

A couple trojans have also been found orbiting with Mars.[note 2]

[edit]Near-Earth asteroids

Main article: Near-Earth asteroids

Near-Earth asteroids, or NEA's, are asteroids that have orbits that pass close to that of Earth. Asteroids that

actually cross the Earth's orbital path are known as Earth-crossers. As of May 2010, 7,075 near-Earth

asteroids are known and the number over one kilometre in diameter is estimated to be 500 - 1,000.

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-57-320.jpg)

![88

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Telescope and Calendar ( Lecture – 3)

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-88-320.jpg)

![123

Day of the week from Gregorian calendar

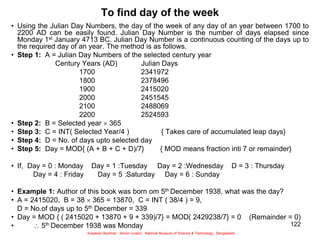

• Stepwise procedure is as follows.

• 1. A = (14 – month)/12 month = January to December 1 To 12

• 2. y = year – A year = 4 digit value

• 3. M = month + 12 A – 2

• 4. D = [ day + y + y/4 – y/100 + y/400 + (31 M)/12]MOD7

• Consider only integer values of the ratios.

• MOD7 means only consider the remainder after dividing by 7.

• According to remainder day is to fixed as follows

• D = 0 : Sunday D = 1 : Monday D = 2 :Tuesday D = 3 :Wednesday

• D = 4 : Thursday D = 5 : Friday D = 6 :Saturday

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-123-320.jpg)

![124

Day of the week from Gregorian calendar

• Example 1: Author of this book was born om 5th December 1938, what was the day?

• 1. A = (14 – month)/12 = (14 – 12)/12 = 2/12 Integer = 0

• 2. y = year – A = 1938 - 0 = 1938 year = 4 digit value

• 3. M = month + 12 A – 2 = 12 + 12 0 – 2 = 10

• 4. In the formula: y/4 = 1938/4 = 484 Integer

y/100 = 1938/100 = 19 Integer

y/400 = 1938/400 = 4 Integer

(31 M)/12 = (31 10)/12 =25 Integer

• 5. D = [ 5 + 1938 + 484 – 19 + 4 + 25]MOD7 = (2437)MOD7 = 1 (remainder)

• 5th December 1938 was Monday

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-124-320.jpg)

![132

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Eclipses and Planets ( Lecture – 4 )

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-132-320.jpg)

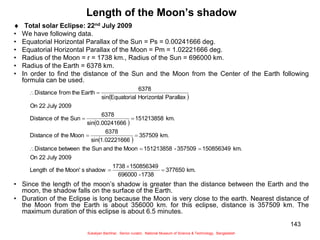

![149

Speed of the shadow in the total solar eclipse

• Every point on the Earth has same angular velocity but different

linear velocity. In general linear velocity at any latitude is given by,

• v= 2Rcos(latitude)/24 km/hr.

• Since the Moon orbits around the Earth, it has also linear velocity,

given by Vm = 2(distance)/(27.3 24 km/hr.

• Since the Earth rotates from west to east and the Moon also

orbits around the Earth from west to east.

• Then we have the speed of the shadow , V = Vm -v

• Example : Total solar Eclipse: 22nd July 2009

• For this eclipse the shadow is moving on an average along 24 degrees north latitudes.

• Linear velocity of the Earth at 24 deg latitude = [2 6400cos(24)]/24 = 1530 km/hr.

• Distance of the Moon from the Earth = 357509 km

• Linear speed of the Moon = [2 357509]/( 27.3 24) = 13428 km/hr.

• Speed of the shadow = 3428 – 1530 = 1898 km/hr.

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-149-320.jpg)

![158

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Magnitudes Of The Stars ( Lecture – 5 )

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-158-320.jpg)

![225

Elementary Astronomical Calculations:

Universe and Space ( Lecture – 6)

•By Sukalyan Bachhar

•Senior Curator

• National Museum of Science & Technology

•Ministry of Science & Technology

•Agargaon, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh

•Tel:+88-02-58160616 (Off), Contact: 01923522660;

•Websitw: www.nmst.gov.bd ; Facebook: Buet Tutor

&

•Member of Bangladesh Astronomical Association

•Short Bio-Data:

First Class BUET Graduate In Mechanical Engineering [1993].

Master Of Science In Mechanical Engineering From BUET [1998].

Field Of Specialization Fluid Mechanics.

Field Of Personal Interest Astrophysics.

Field Of Real Life Activity Popularization Of Science & Technology From1995.

An Experienced Teacher Of Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry for O- ,A- , IB- &

Undergraduate Level.

Habituated as Science Speaker for Science Popularization.

Experienced In Supervising For Multiple Scientific Or Research Projects.

17 th BCS Qualified In Cooperative Cadre (Stood First On That Cadre).

Sukalyan Bachhar, Senior curator, National Museum of Science & Technology, Bangladesh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementaryastronomicalcalculations-241009113137-88e5982a/85/Elementary-Astronomical-Calculations-pdf-225-320.jpg)