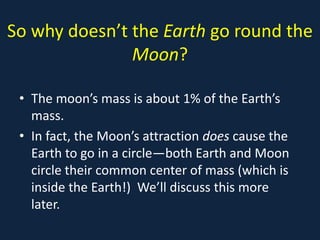

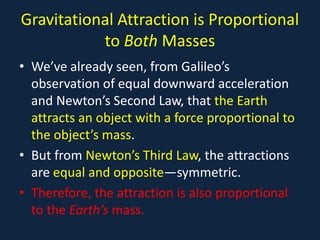

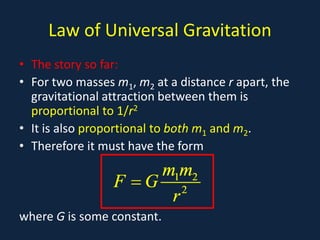

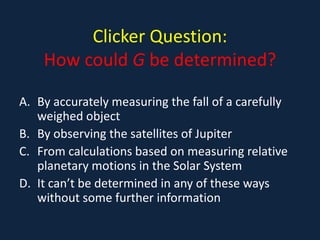

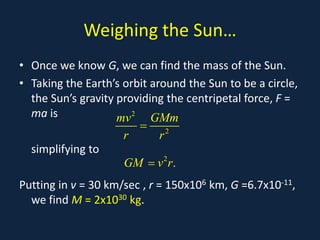

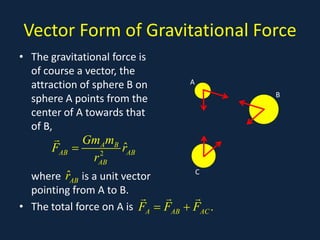

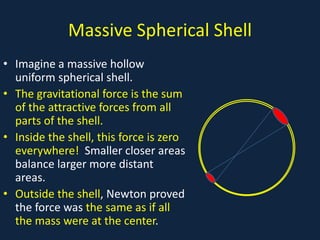

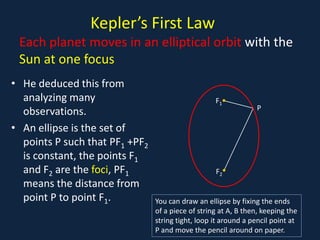

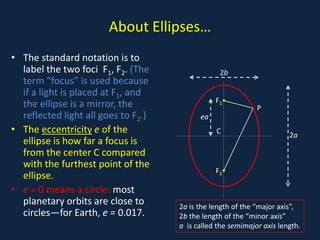

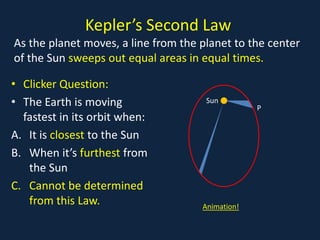

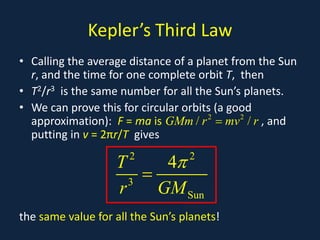

The document discusses key concepts of gravitation and Newton's law of universal gravitation. It explains that gravitational force follows an inverse square law with distance and is proportional to the masses of both objects. It describes how Cavendish used experiments to determine the gravitational constant G and calculate the mass of the Earth. Kepler's laws of planetary motion are also summarized.