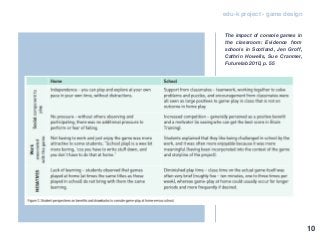

The document discusses the advantages of game-based learning in educational settings, emphasizing its ability to enhance student engagement, collaboration, and retention of knowledge. It highlights the pivotal role of gaming environments in fostering active learning and motivation, as well as the observed educational benefits from students' perspectives. Additionally, it addresses challenges such as curriculum integration and teacher preparedness for effectively implementing game-based learning in classrooms.

![edu-k project - game design

“The majority of school leaders viewed these projects as highly

successful and are enthusiastic about their impact: “I’ve never

been so convinced about the way forward with things. My absolute

dream is to have a games console in every class permanently.“

Success with game-based learning is repeatedly linked by senior

leaders to the pedagogical skill of the teacher involved. The game

is often described as the hook or the stimulus and is never an end

in itself. […] Impact on the pupils: One primary headteacher re-

flected the views of many of the school leaders when he said, “As

a motivational tool it has been unsurpassed....these kids are

learning without realising.””

“The stories of enthused, engaged and highly motivated pupils are

manifold: pupils who had been reluctant to come school turning up

at 8.30 am to rehearse; pupils who rarely wrote more than a para-

graph writing at length; pupils who never did their homework bring-

ing in the fruits of their research unprompted; pupils who found

group work impossible blending in to group tasks and even sup-

porting others; pupils with behaviour problems settling down; sum-

mer term P7 pupils on task and inspired. […] There were accounts

of hierarchies being flattened, as less academic and confident chil-

dren increasingly demonstrated their game skills, confidence and

self-esteem being built through natural peer-tutoring opportunities

afforded by the game.”

The impact of console games in

the classroom: Evidence from

schools in Scotland, Jen Groff,

Cathrin Howells, Sue Cranmer,

Futurelab 2010, p. 30, 31, 49

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eduk-quotes-report-150402132809-conversion-gate01/85/Eduk-quotes-report-9-320.jpg?cb=1723629682)

![edu-k project - game design

“To greatly oversimplify his theory for the purpose of comparison,

he claims that people are driven by a will to mastery (challenge) to

seek optimally informative environments (curiosity) which they as-

similate, in part, using schemas from other contexts (fantasy).”

“Piaget (1951) explains fantasy in children’s play primarily as an

attempt to “assimilate” experience into existing structures in the

child’s mind with minimal needs to “accommodate” to the de-

mands of external reality. [...] I define a fantasy-inducing environ-

ment as one that evokes “mental images of things not present to the

senses or within the actual experience of the person involved”. [...]

It seems fair to say, however, that computer games that embody

emotionally-involving fantasies like war, destruction, and competi-

tion are likely to be more popular than those with less emotional

fantasies.”

“Curiosity. One of the most important features of intrinsically mo-

tivating environments is the degree to which they can continue to

arouse and then satisfy our curiosity. [...] it involves surprisingness

with respect to the knowledge. [...] Berlyne (1965) goes further and

claims that the principal factor producing curiosity is what he calls

conceptual conflict. By this he means conflict between incompat-

ible attitudes or ideas evoked by a stimulus situation.”

Toward a Theory of Intrinsically

Instruction, Thomas W. Malone,

Xerox Palo AIto Research Cent-

er 1981, p. 356, 337 - 338

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eduk-quotes-report-150402132809-conversion-gate01/85/Eduk-quotes-report-21-320.jpg?cb=1723629682)

![edu-k project - game design

“Social groups exist to induct newcomers into distinctive experi-

ences, and ways of interpreting and using those experiences, for

achieving goals and solving problems. [...] Gamers often organize

themselves into communities of practice that create social identi-

ties with distinctive ways of talking, interacting, interpreting experi-

ences, and applying values, knowledge, and skill to achieve goals

and solve problems. This is a crucial point for those who wish to

make so-called serious games: to gain these sorts of desired learn-

ing effects will often require as much care about the social system

(the learning system) in which the game is placed as the in-game

design itself.” Learning and Games

“In terms of the social dynamics of game-based learning, a com-

mon theme is that through video games young people cultivate

interests and join ‘affinity groups’ that operate across contexts, as

part of their projects of personal development. In these groups,

players engage in sophisticated forms of learning fuelled by the

shared passion for gaming. […] A similar, and equally popular,

theme is that video games provide virtual worlds which are effec-

tive contexts for learning, because acting in such worlds allows

learners to develop social practices and take on the identities of

actual professional communities.”

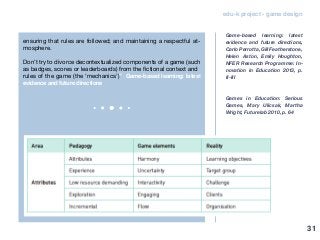

Game-based learning: latest

evidence and future directions,

Carlo Perrotta, Gill Featherstone,

Helen Aston, Emily Houghton,

NFER Research Programme: In-

novation in Education 2013, p. 6,

17

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eduk-quotes-report-150402132809-conversion-gate01/85/Eduk-quotes-report-31-320.jpg?cb=1723629682)

![edu-k project - game design

scientific theories: completeness, consistency, and parsimony.

[...] According to this theory, the way to engage learners’ curiosity

is to present just enough information to make their existing knowl-

edge seem incomplete, inconsistent, or unparsimonious. The learn-

ers are then motivated to learn more, in order to make their cogni-

tive structures better-formed. [...] The “Socratic method” and the

tutorial strategies of master teachers (Collins & Stevens, 1981) can

be seen as ways of systematically exposing incompletenesses, in-

consistencies, and unparsimoniousness in the learner’s knowledge

structures.” Toward a Theory of Intrinsically Instruction

“The RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification:

Play – facilitating the freedom to explore and fail within boundaries.

Exposition – creating stories for participants that are integrated

with the real-world setting and allowing them to create their own.

Choice – developing systems that put the power in the hands of

the participants.

Toward a Theory of Intrinsically

Instruction, Thomas W. Malone,

Xerox Palo AIto Research Cent-

er 1981, p. 363

The recipe for Meaningful Gami-

fication, Scott Nicholson, Wood,

L & Reiners 2012., p. 4

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eduk-quotes-report-150402132809-conversion-gate01/85/Eduk-quotes-report-43-320.jpg?cb=1723629682)