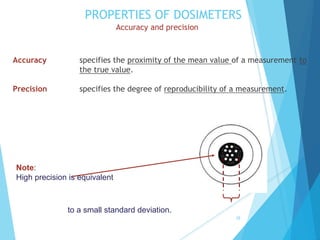

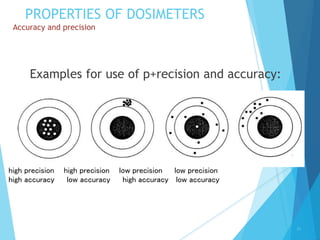

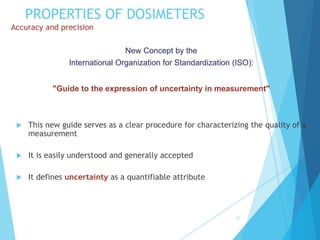

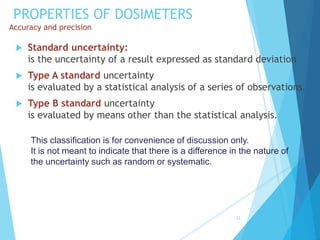

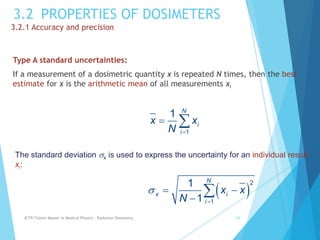

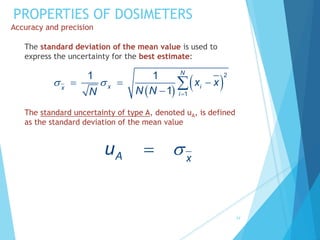

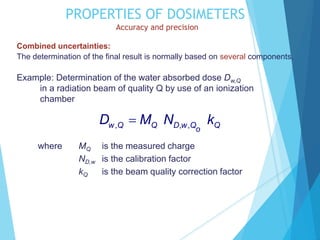

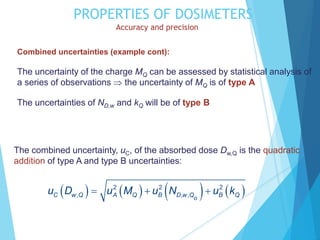

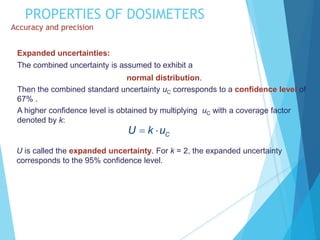

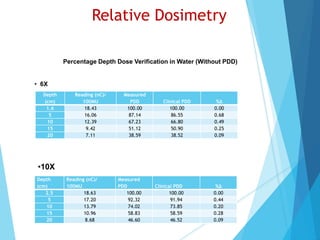

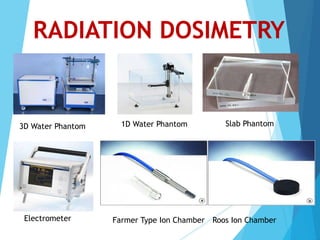

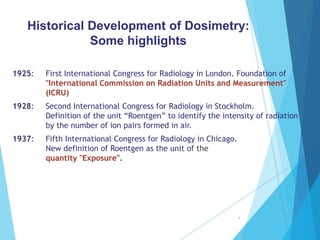

MD. Motiur Rahman is the Chief Medical Physicist and Assistant Project Director at TMSS Cancer Center in Bogura, Bangladesh. The document discusses the history and importance of radiation dosimetry in cancer treatment. It describes how radiation dose is measured using instruments like ionization chambers placed in the radiation beam. Dose measurements must be standardized according to dosimetry protocols to ensure cancer patients receive the prescribed radiation amounts accurately. Absolute and relative dosimetry methods are outlined as well as factors like accuracy, precision, and uncertainty which are important for high quality dose measurements.

![What is Absolute dosimetry?

Absolute dosimetry is a direct measure of ionization or

absorbed dose under standard conditions, which are

things like calorimetry [measure energy deposited

which eventually appears as heat], electrons released

(in an ionization chamber where electronic charge is

measured), or ion formation where the number of

valence changes in a known amount of ions is directly

related to the number of electrons (chemical

dosimeter).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dosimetry-210327175146/85/Dosimetry-9-320.jpg)