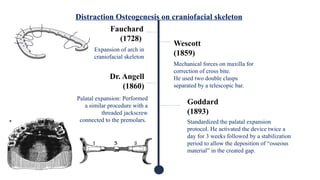

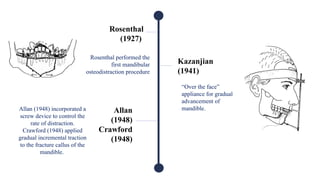

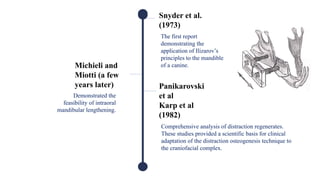

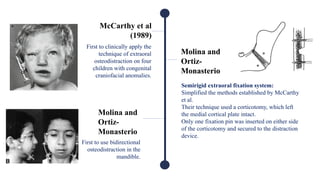

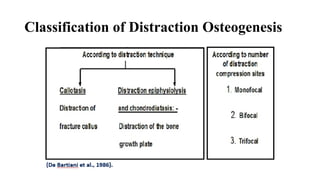

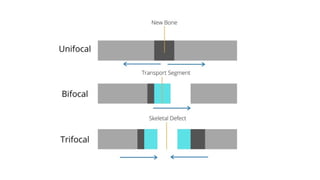

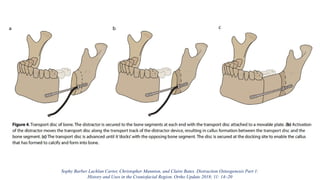

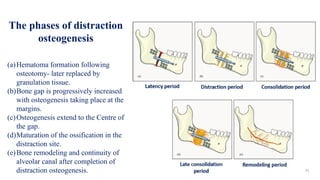

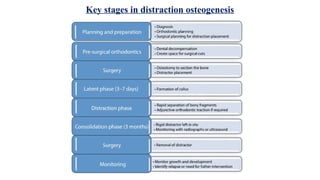

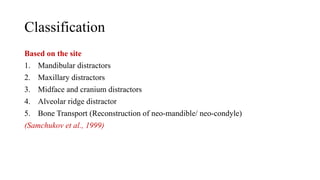

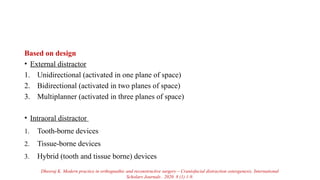

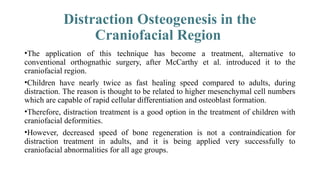

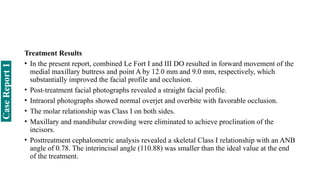

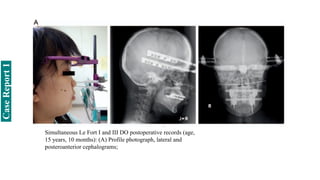

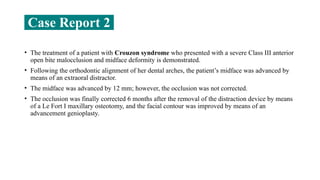

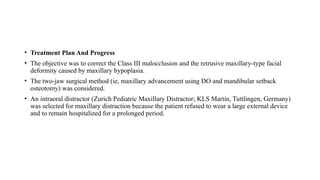

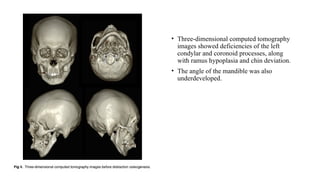

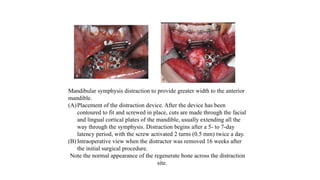

Distraction osteogenesis is a surgical technique used to induce new bone formation by gradually separating osteotomized bone segments, particularly beneficial in craniofacial reconstruction. The document elaborates on the history, principles, mechanisms, and implications of distraction osteogenesis, as well as its effects on both bone and surrounding soft tissues. It covers the procedure phases, classifications, and advancements in techniques, highlighting its significance in addressing congenital and acquired craniofacial anomalies.

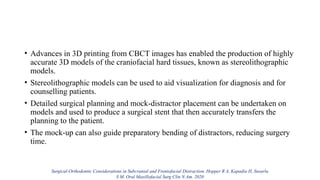

![Research and advances

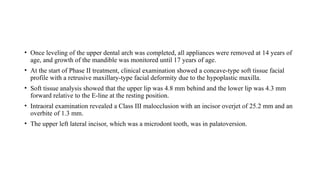

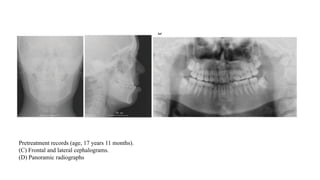

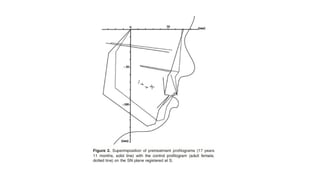

Automated continuous DO

• Currently available distraction devices are patient and surgeon dependent. The

patient must adjust the manual control two or more times daily, often over long

periods.

Hariri F, Yoong Chin S, Rengarajoo J, Chao Foo Q, Nur Nabihah Zainul Abidin S, Fadhli Ahmad Badruddin A. Distraction Osteogenesis in

Oral and Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive Surgery [Internet]. Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. IntechOpen; 2019.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/distractionosteogenesis-241219123140-a9305f3e/85/Distraction-Osteogenesis-orthodontics-pptx-257-320.jpg)

![• Because non-compliance and device failure are the leading causes of treatment

failure, the patient requires numerous clinical visits to ensure proper distractor

activation.

• Considering these drawbacks, many research groups are working to design novel

distraction devices that expand automatically and continuously. An automated

mechanism would eliminate the need for patient compliance and decrease the

frequency of post-operative visits for patient supervision.

• At the moment, the types of these devices are classified into three categories

based on the method of power: hydraulic, motor-driven and spring-mediated

Hariri F, Yoong Chin S, Rengarajoo J, Chao Foo Q, Nur Nabihah Zainul Abidin S, Fadhli Ahmad Badruddin A. Distraction Osteogenesis in

Oral and Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive Surgery [Internet]. Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. IntechOpen; 2019.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/distractionosteogenesis-241219123140-a9305f3e/85/Distraction-Osteogenesis-orthodontics-pptx-258-320.jpg)