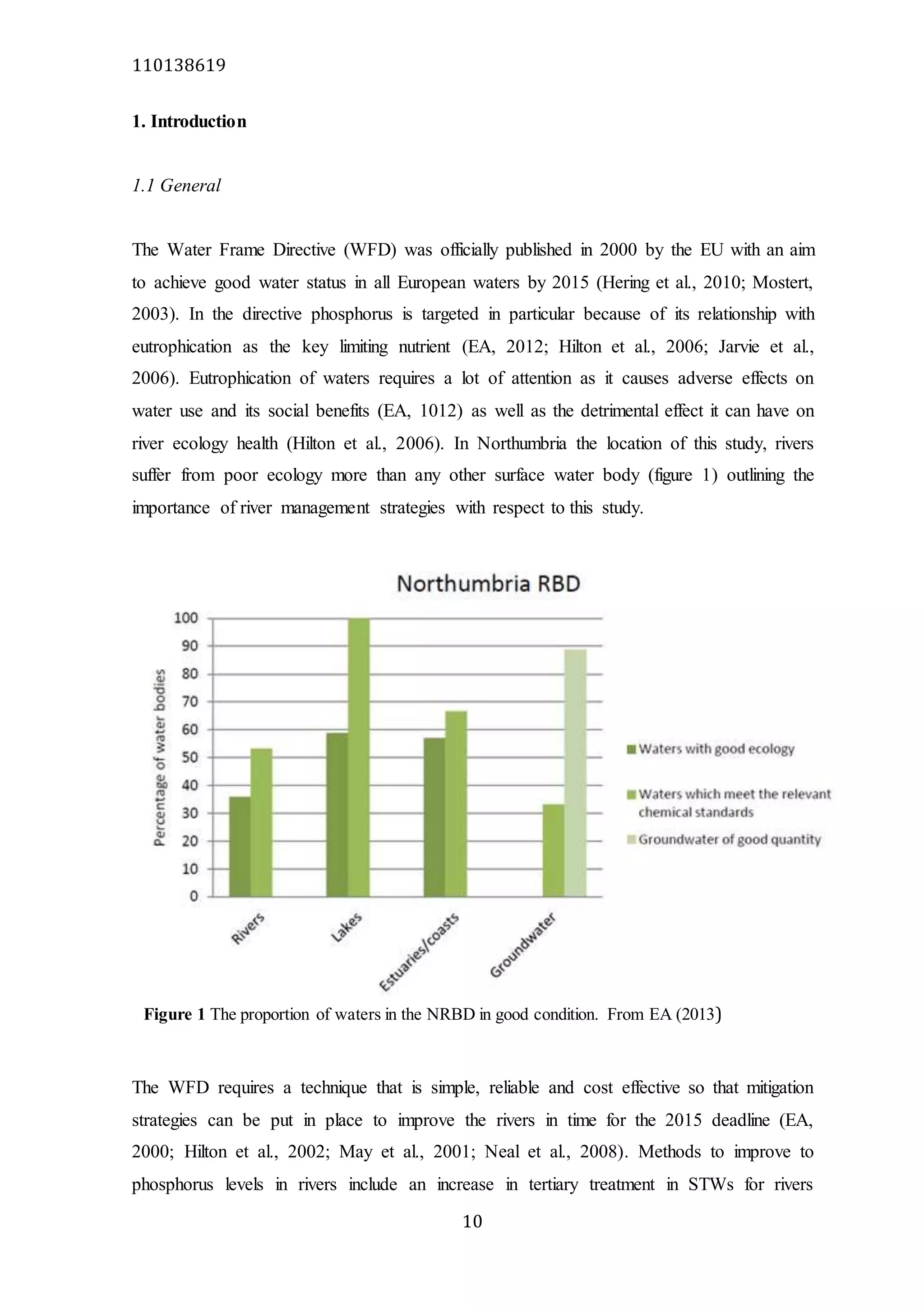

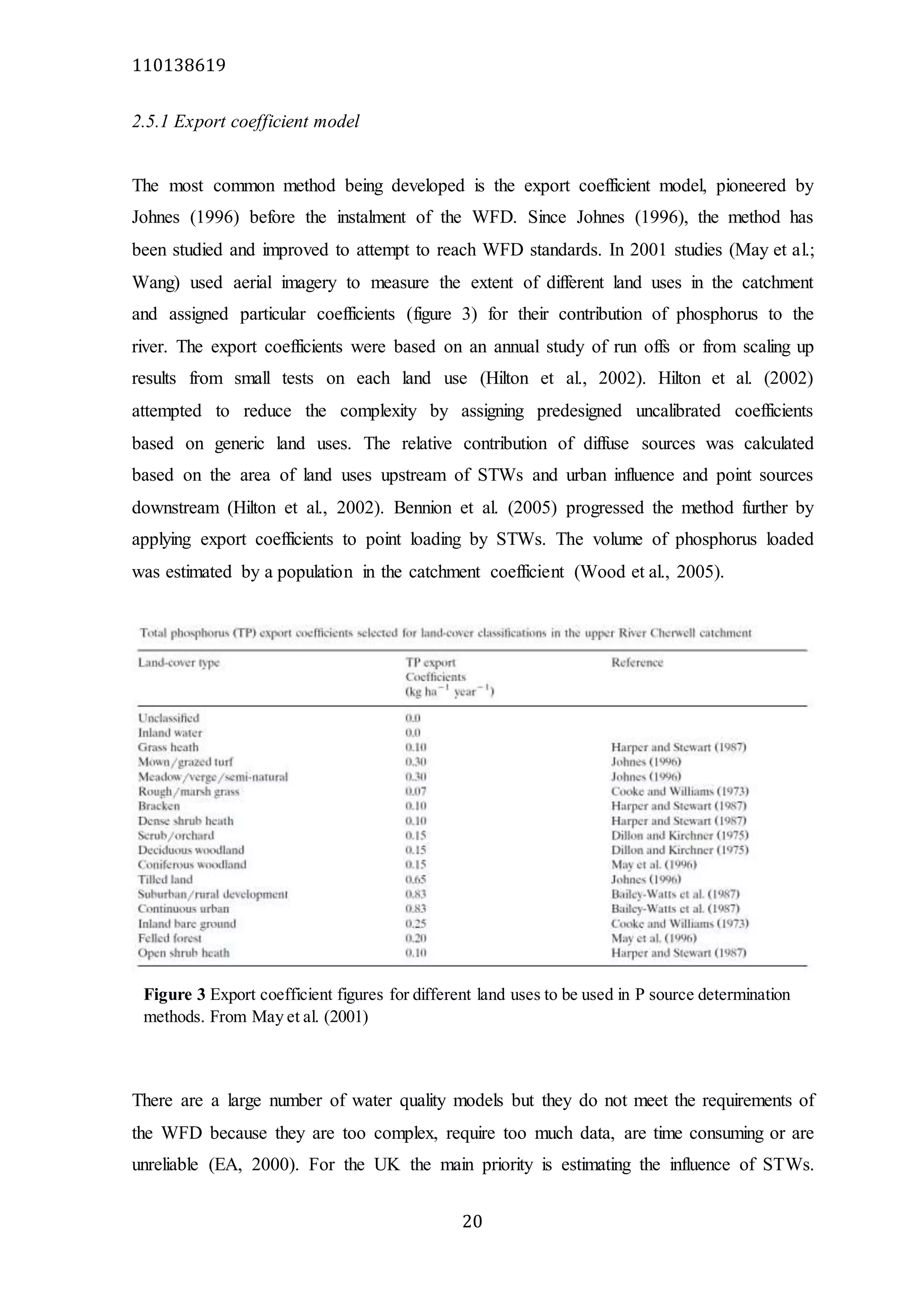

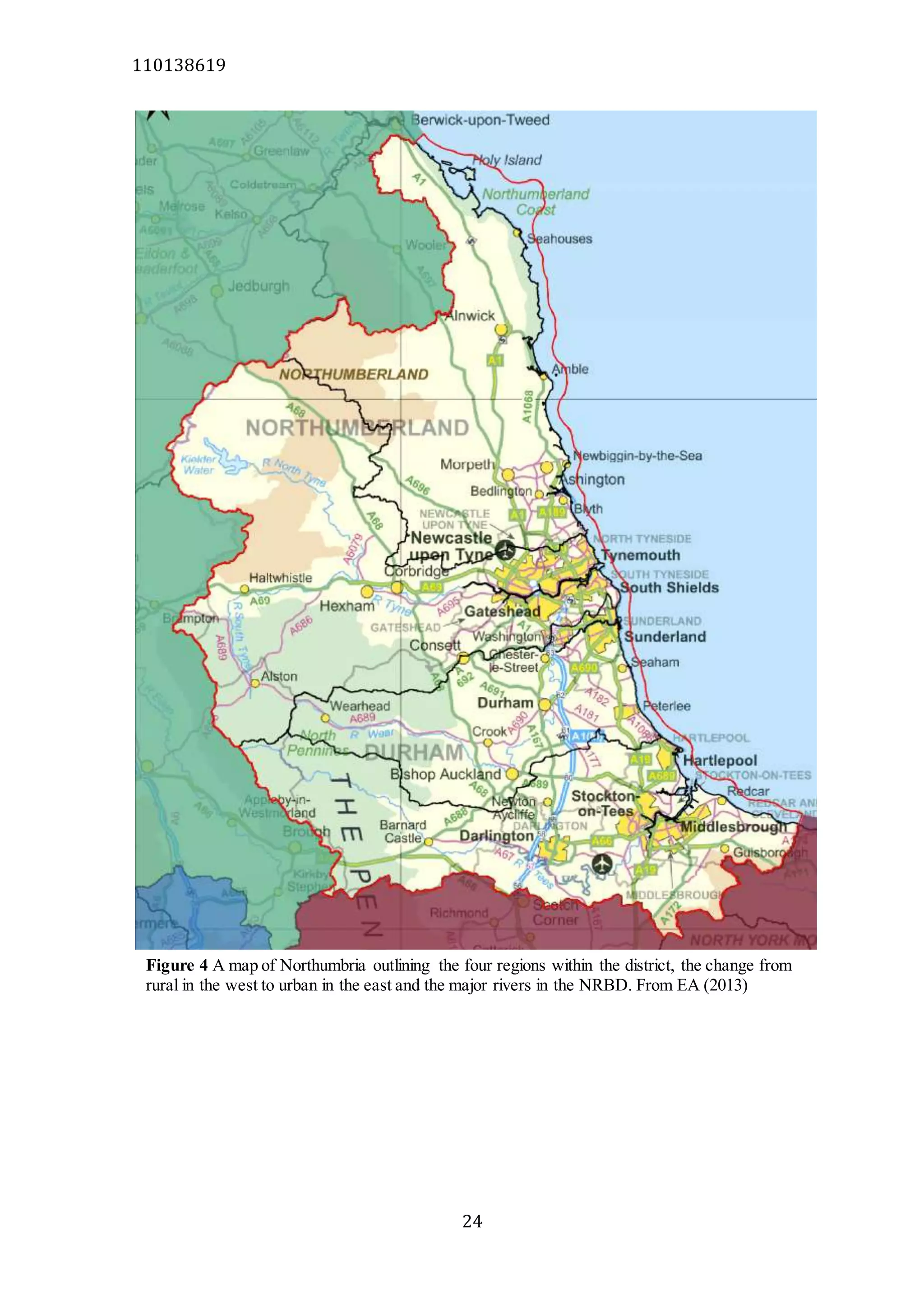

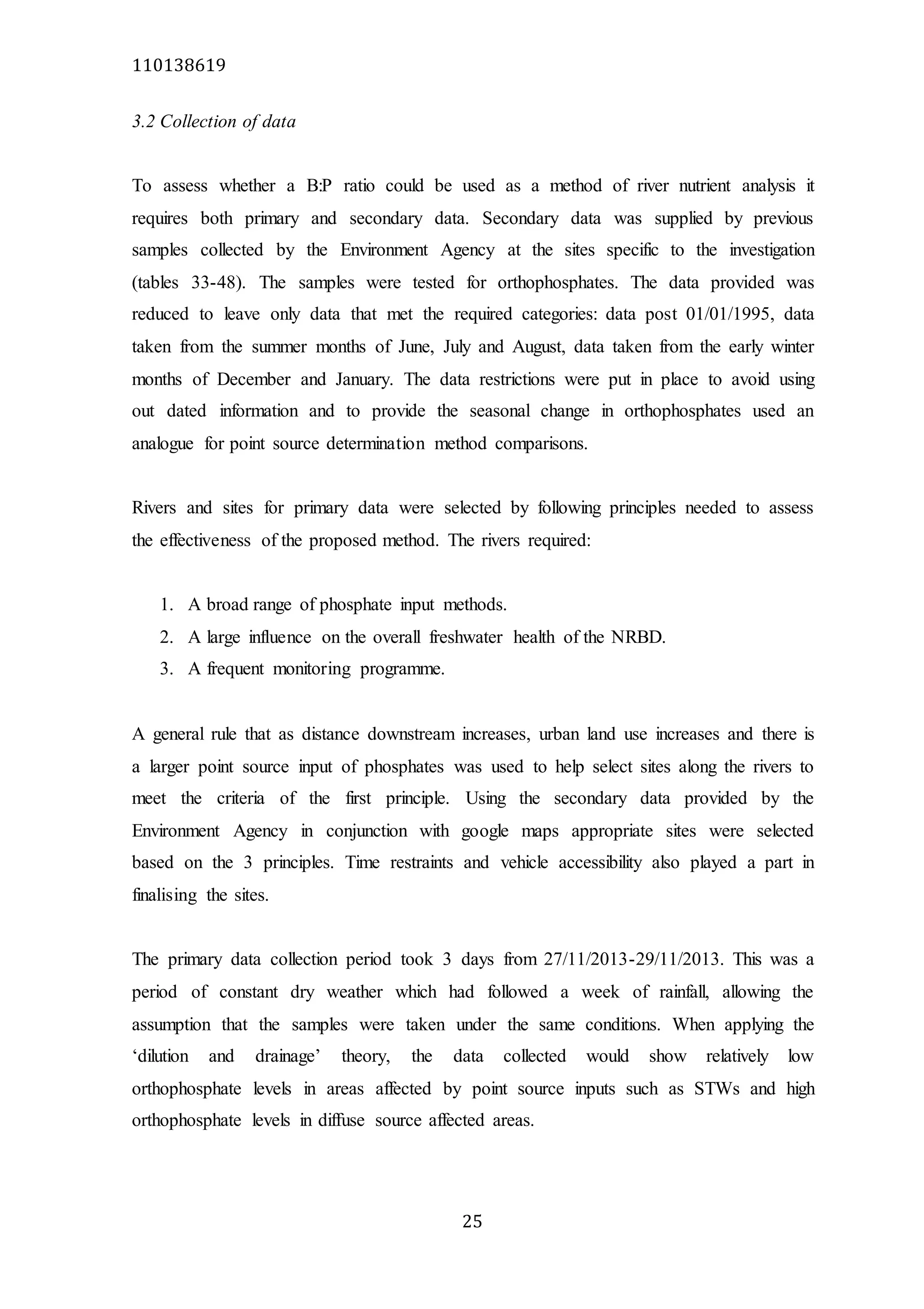

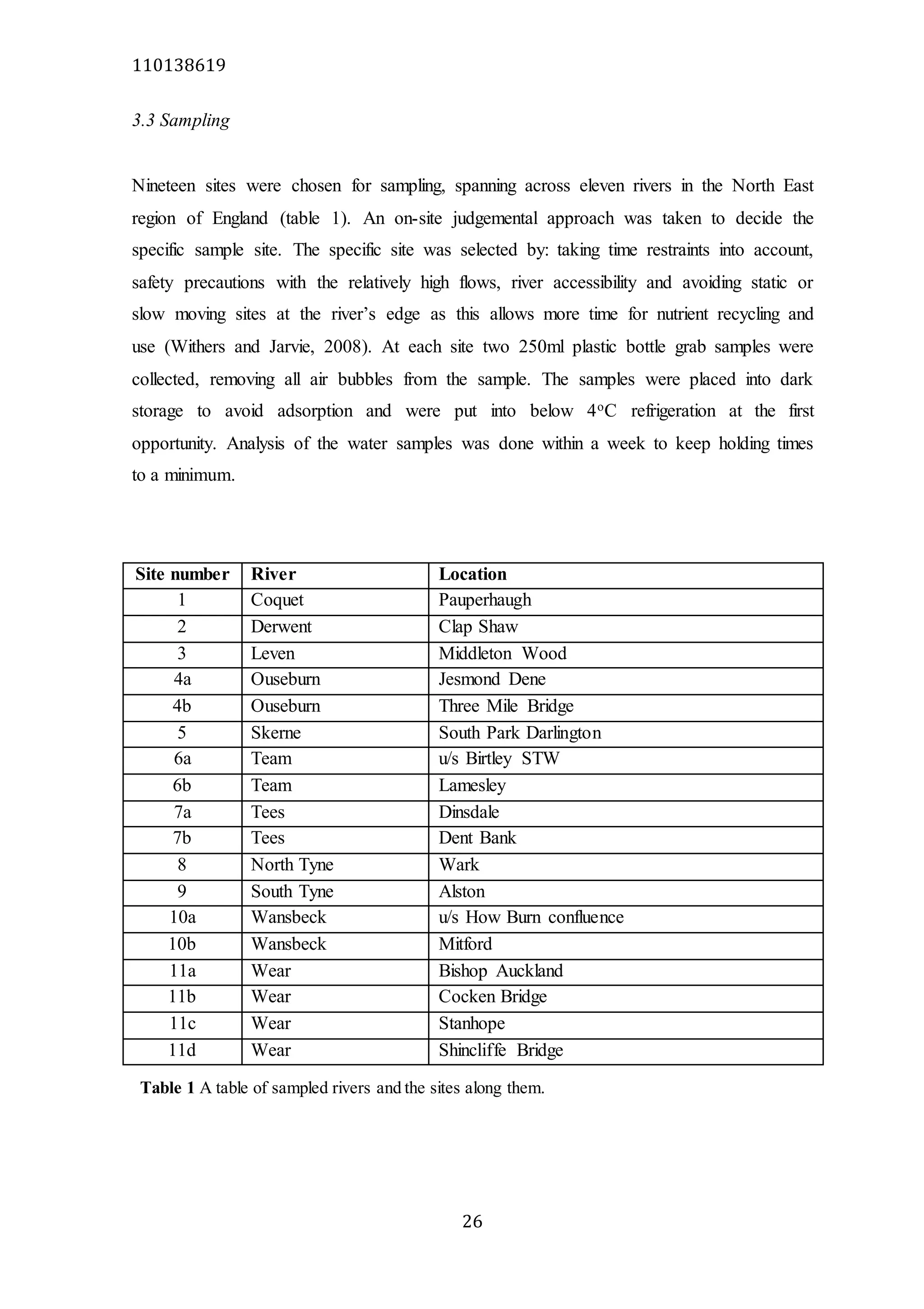

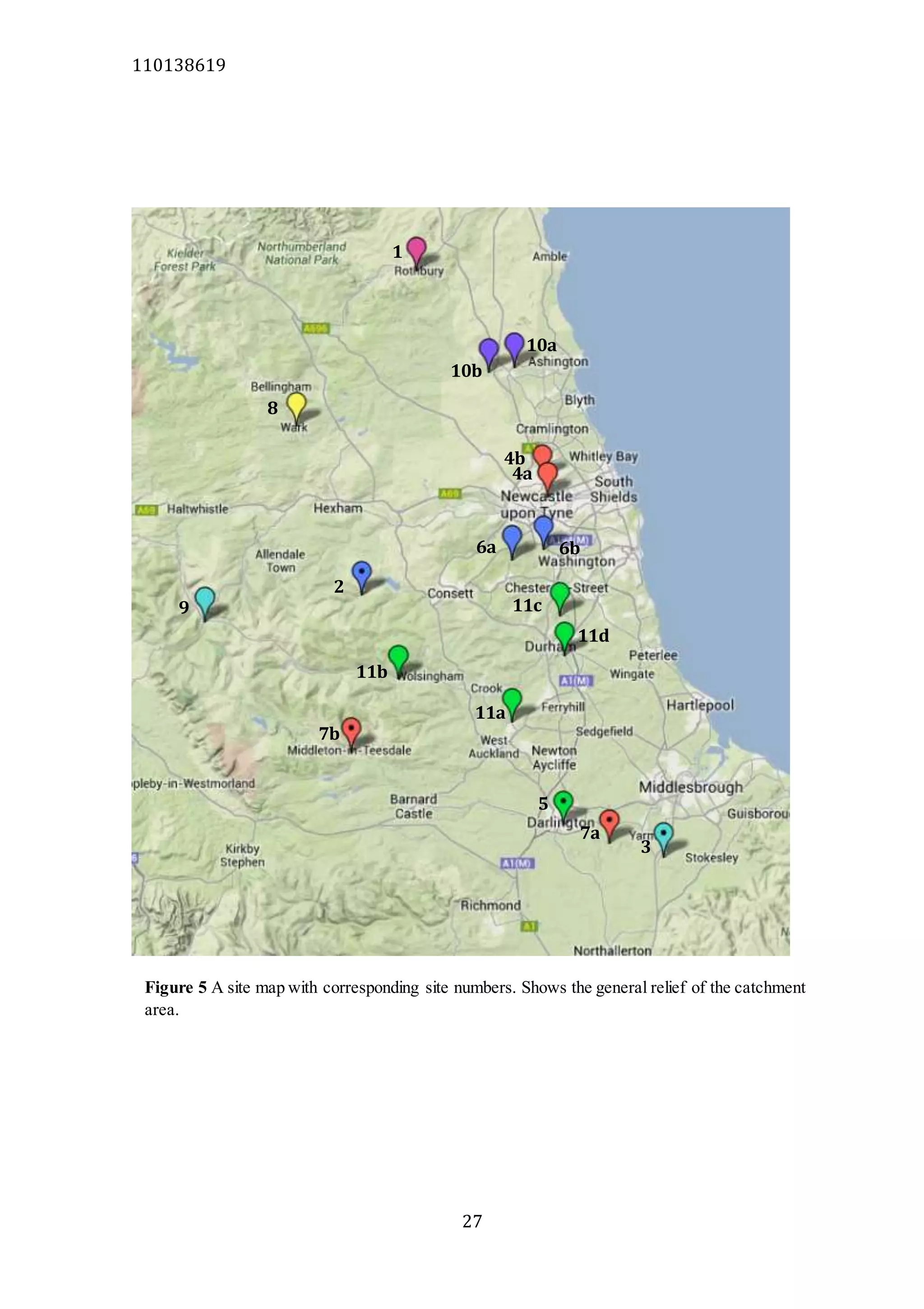

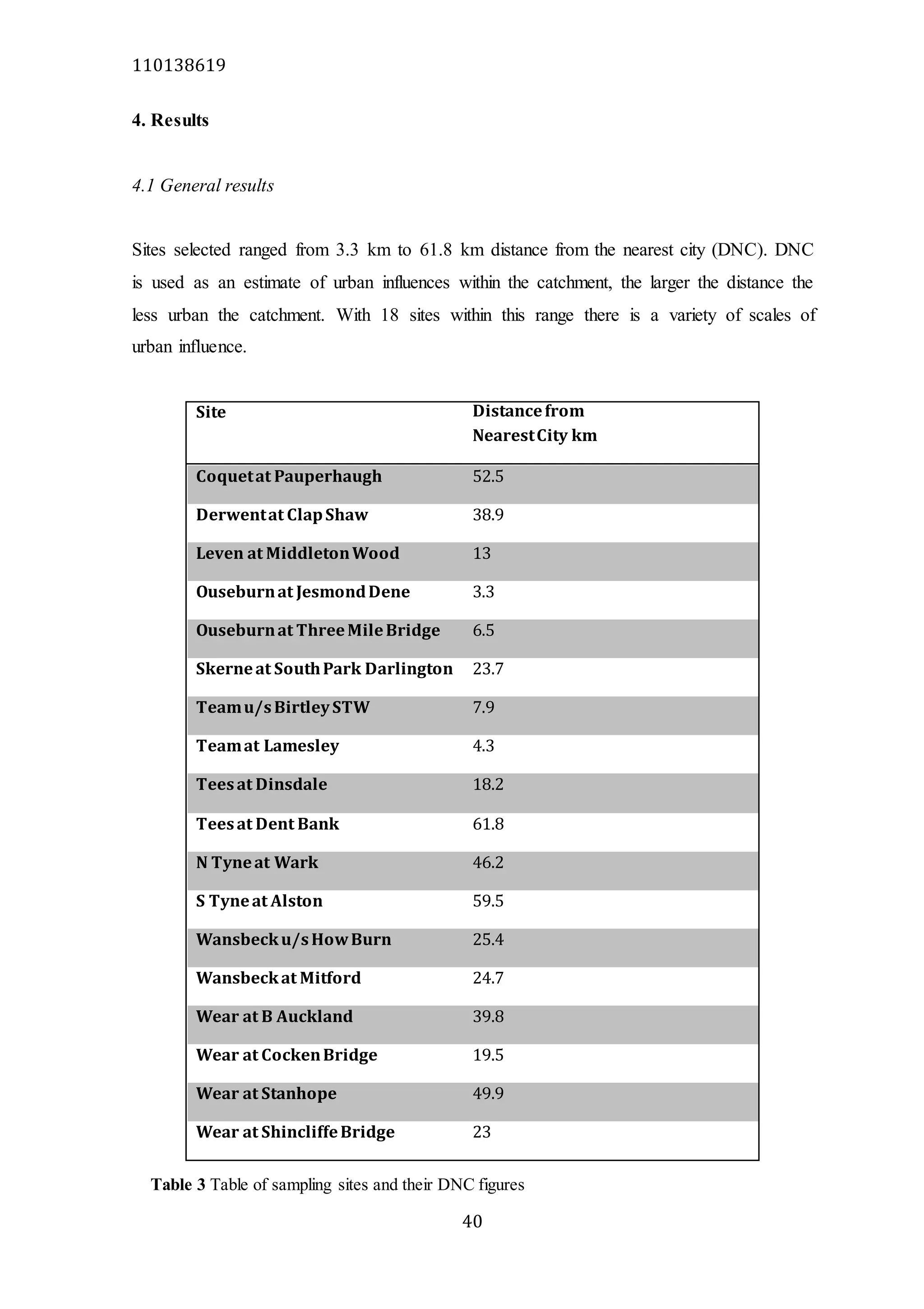

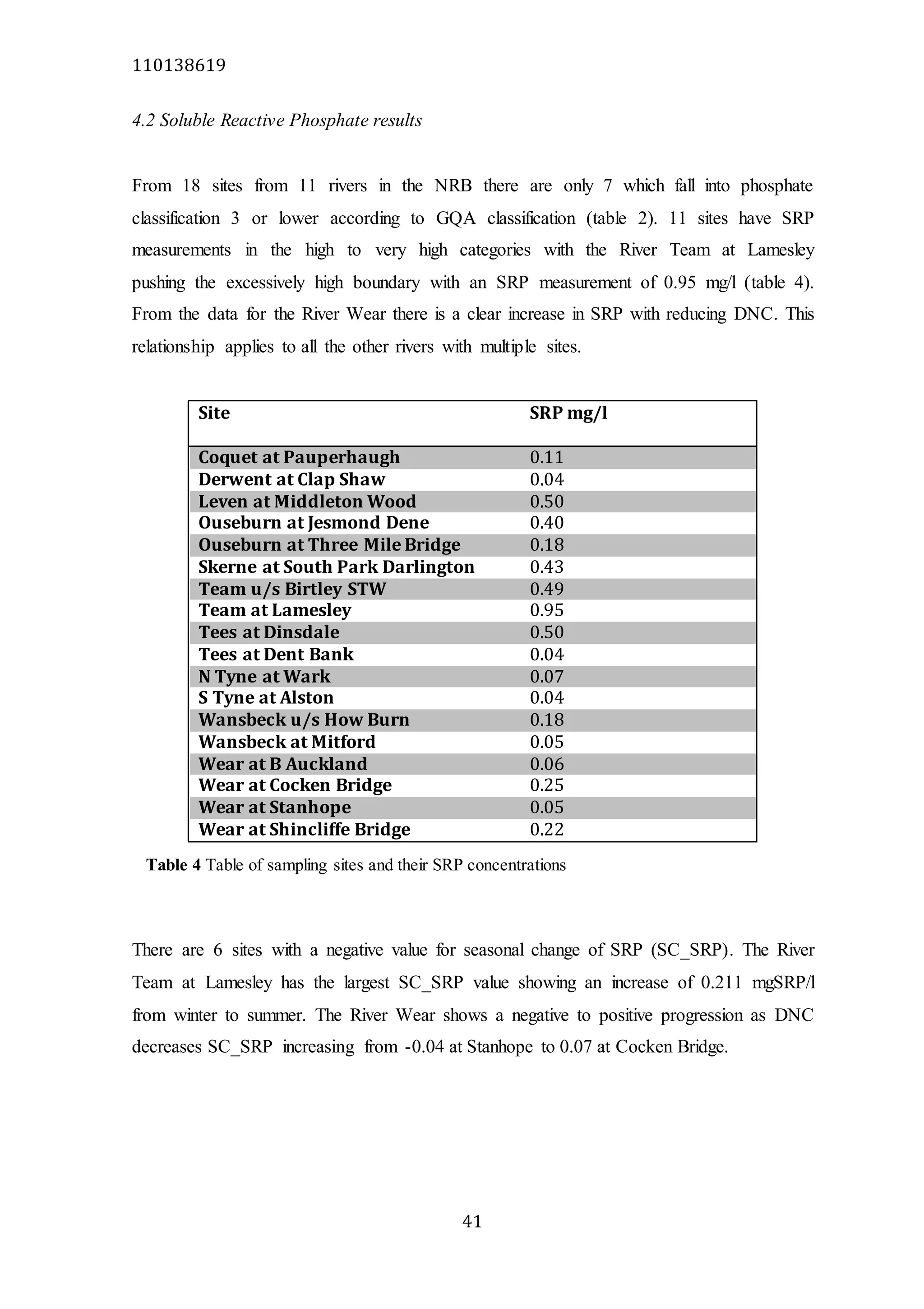

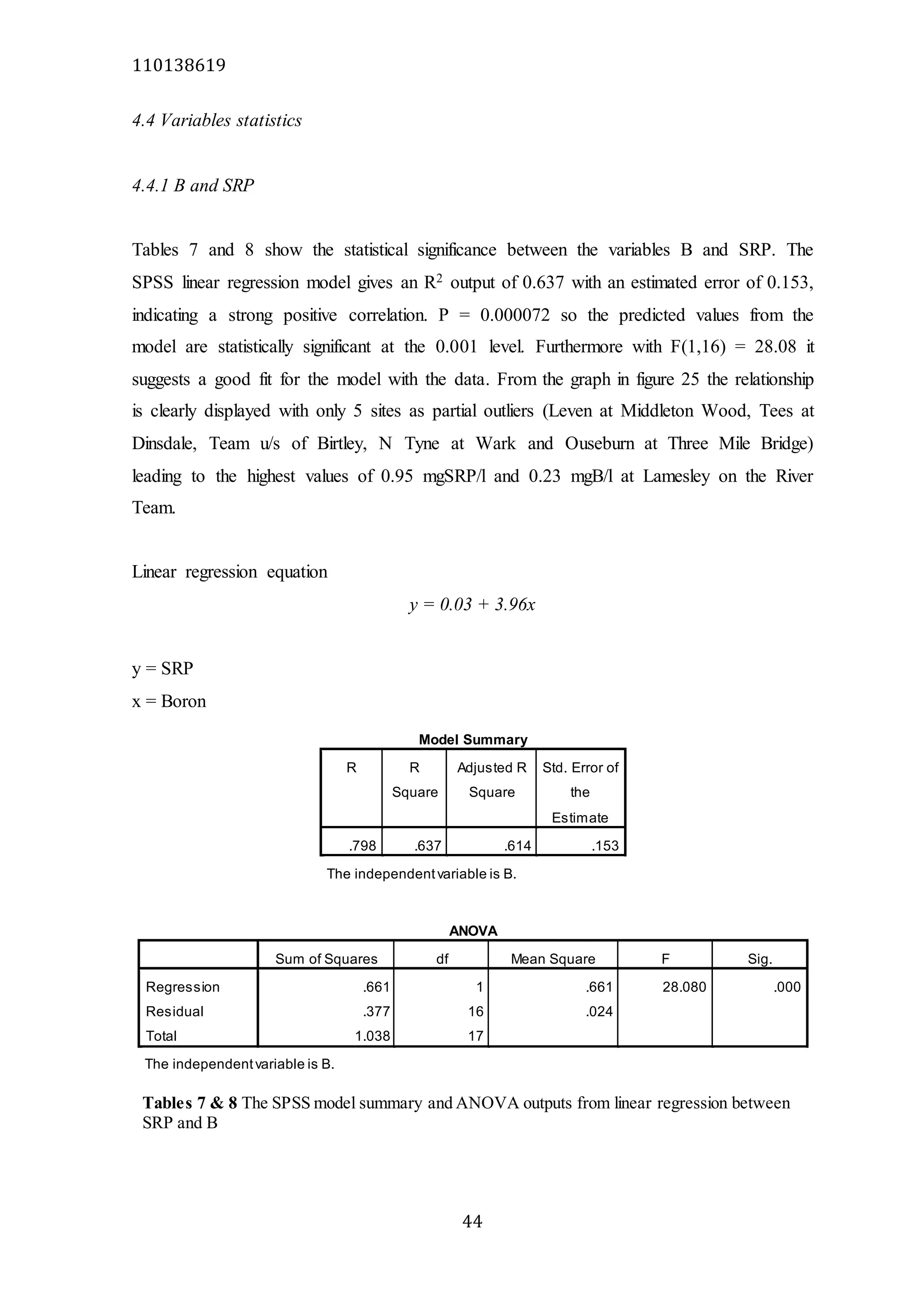

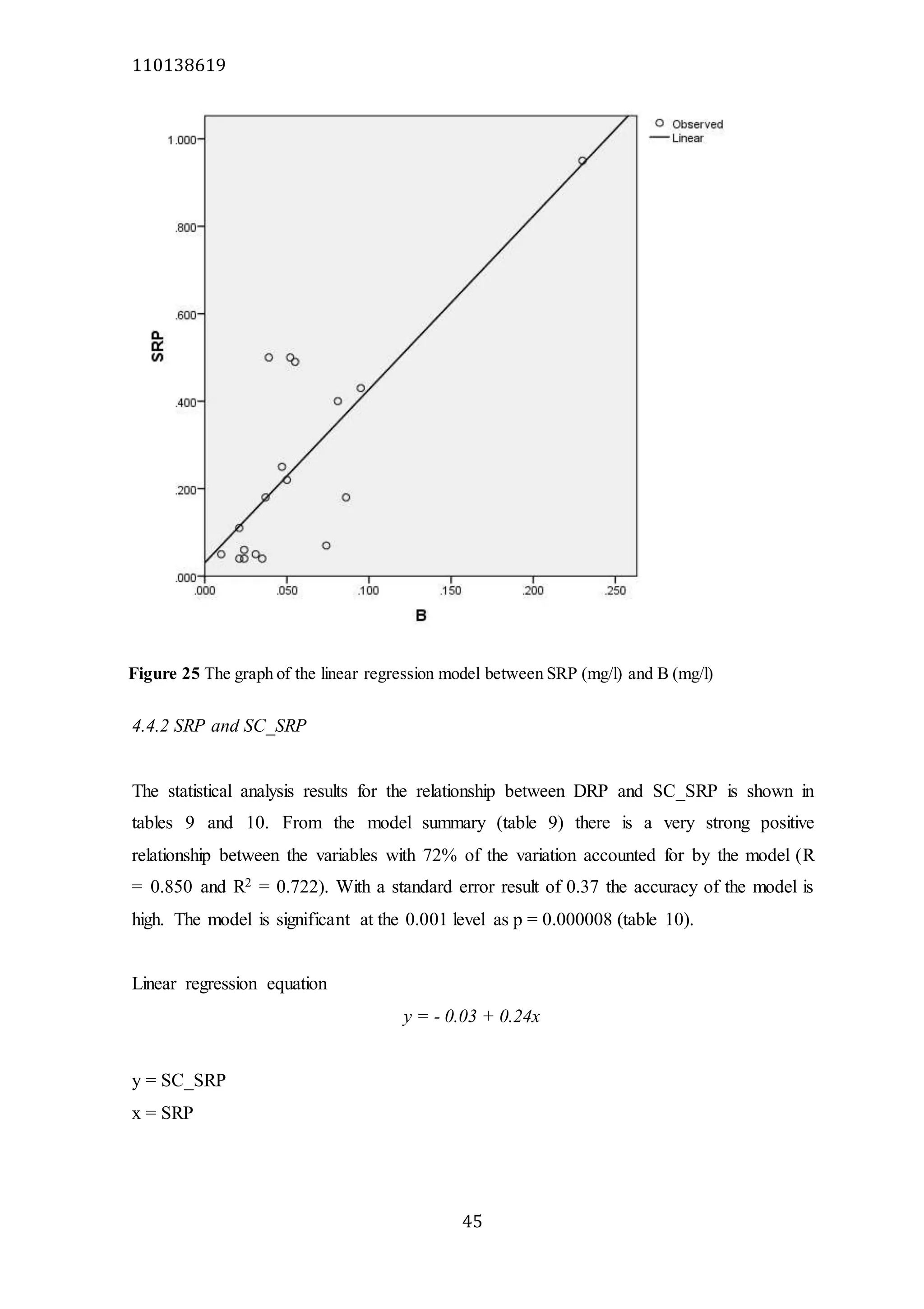

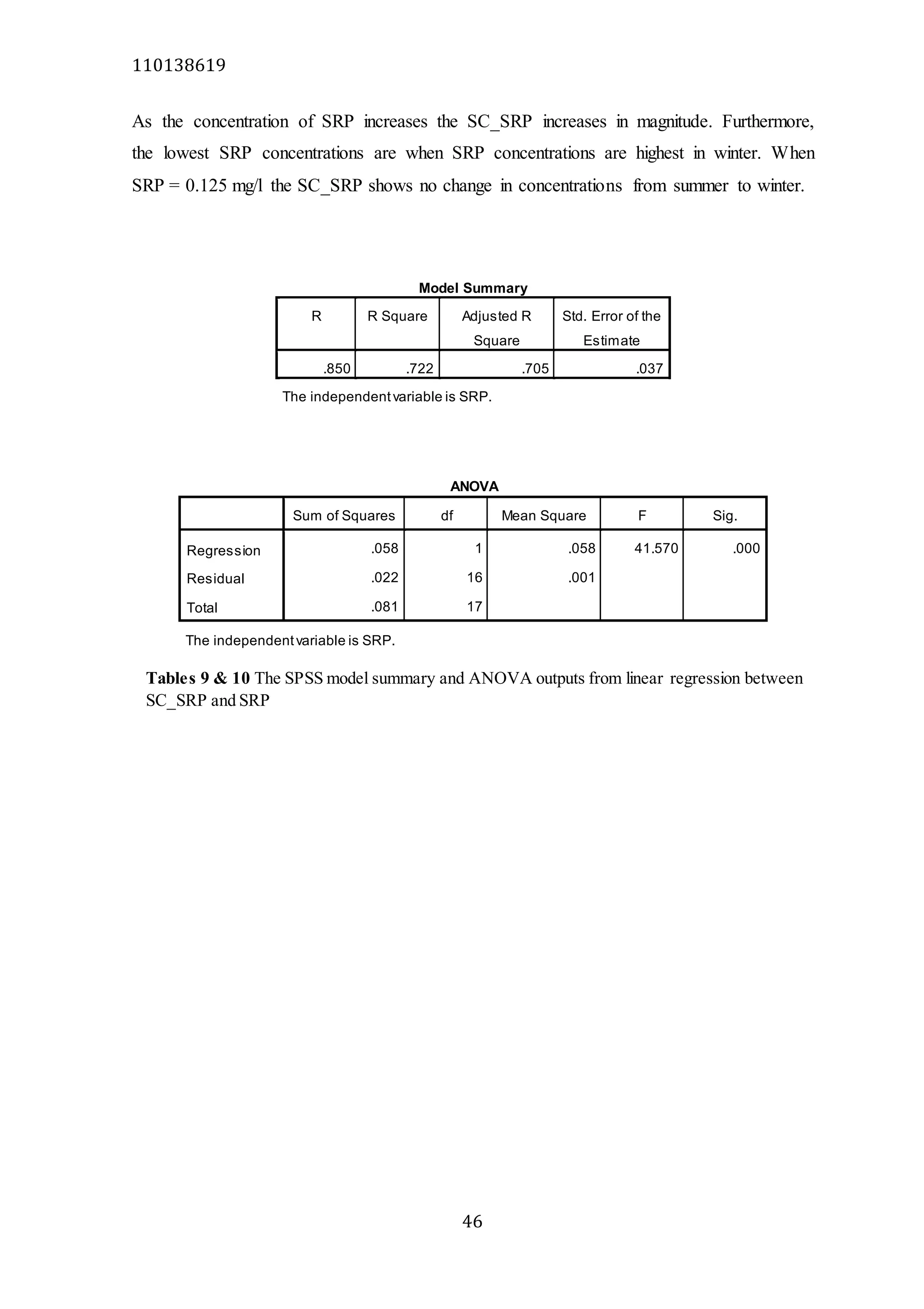

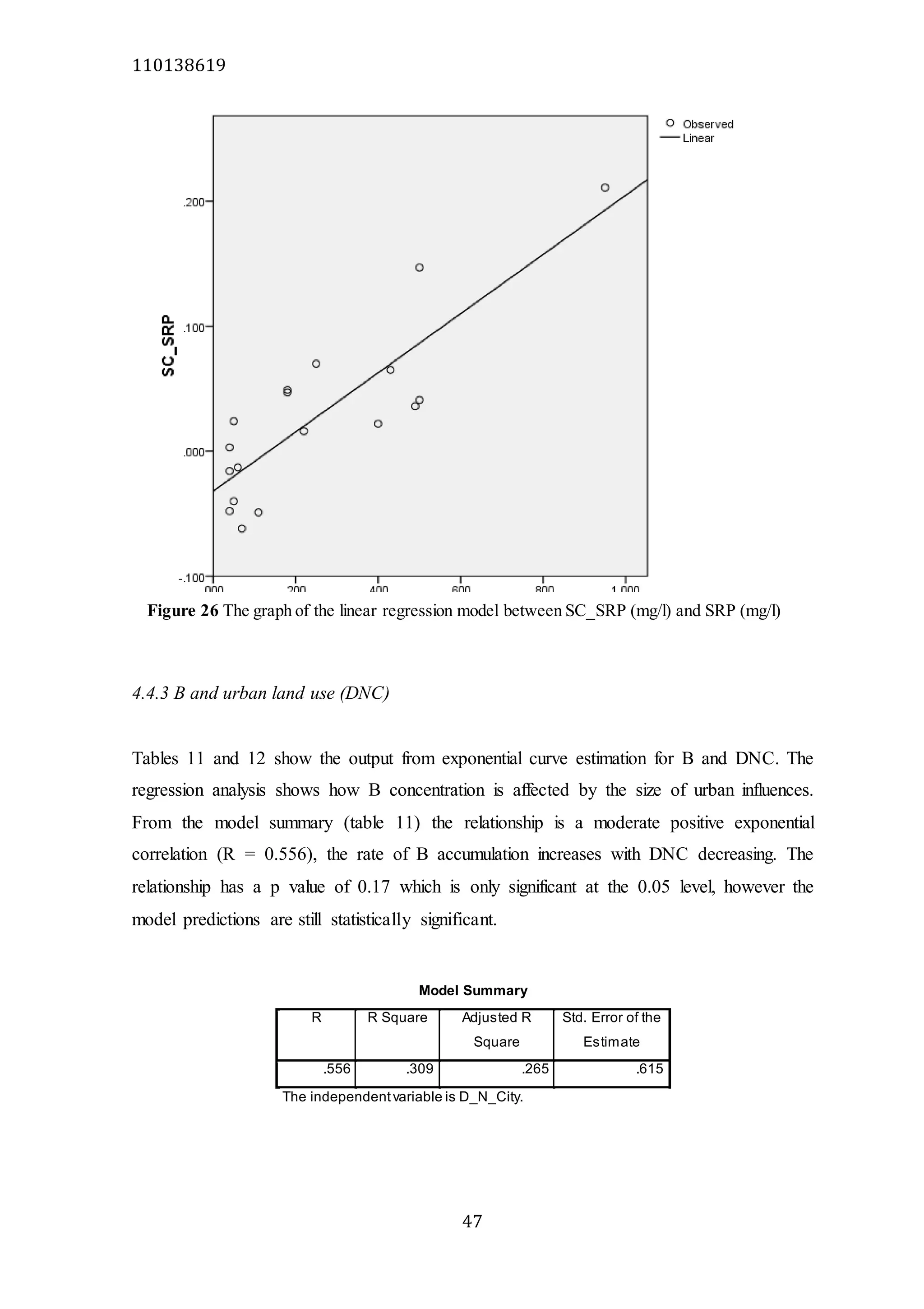

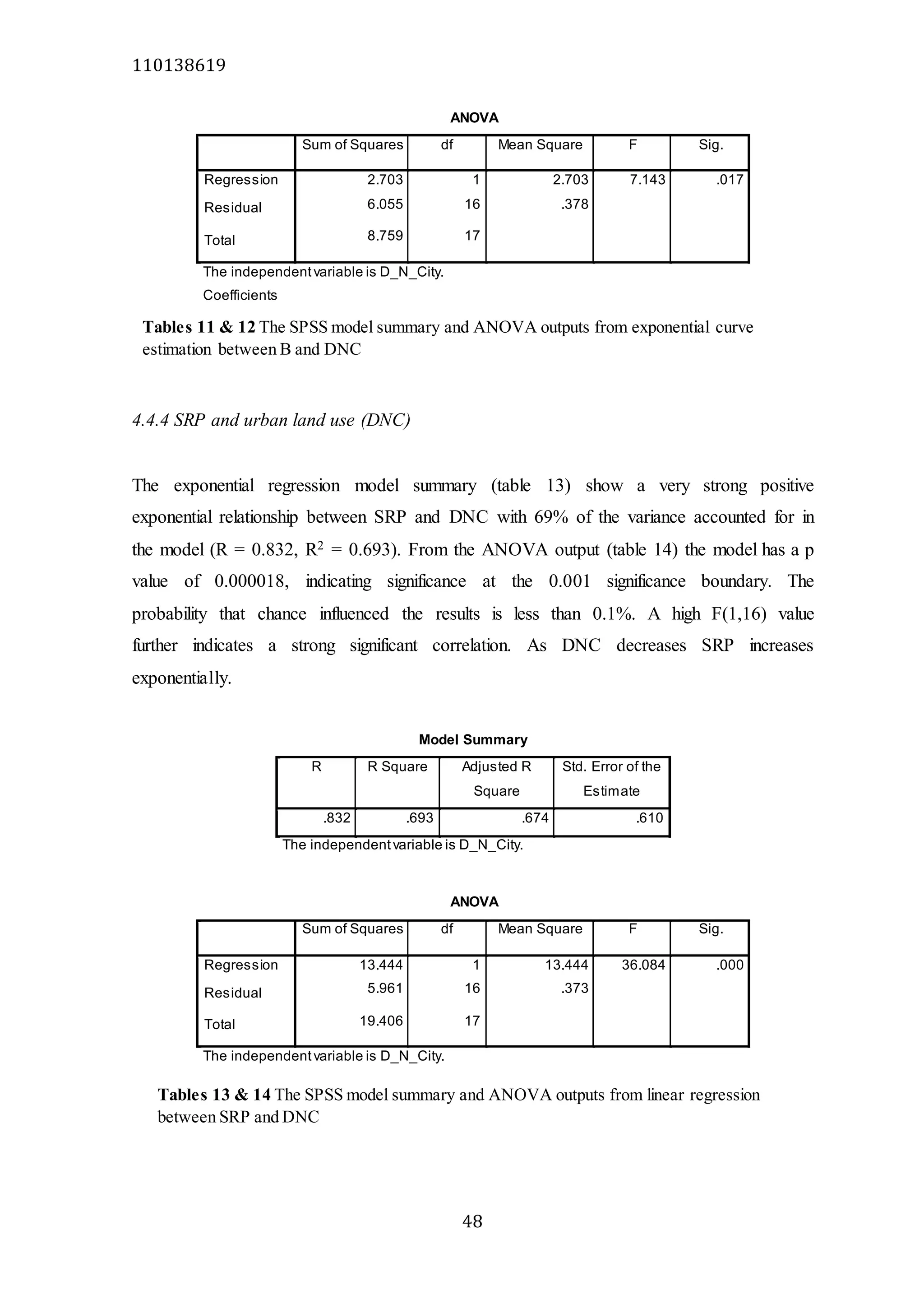

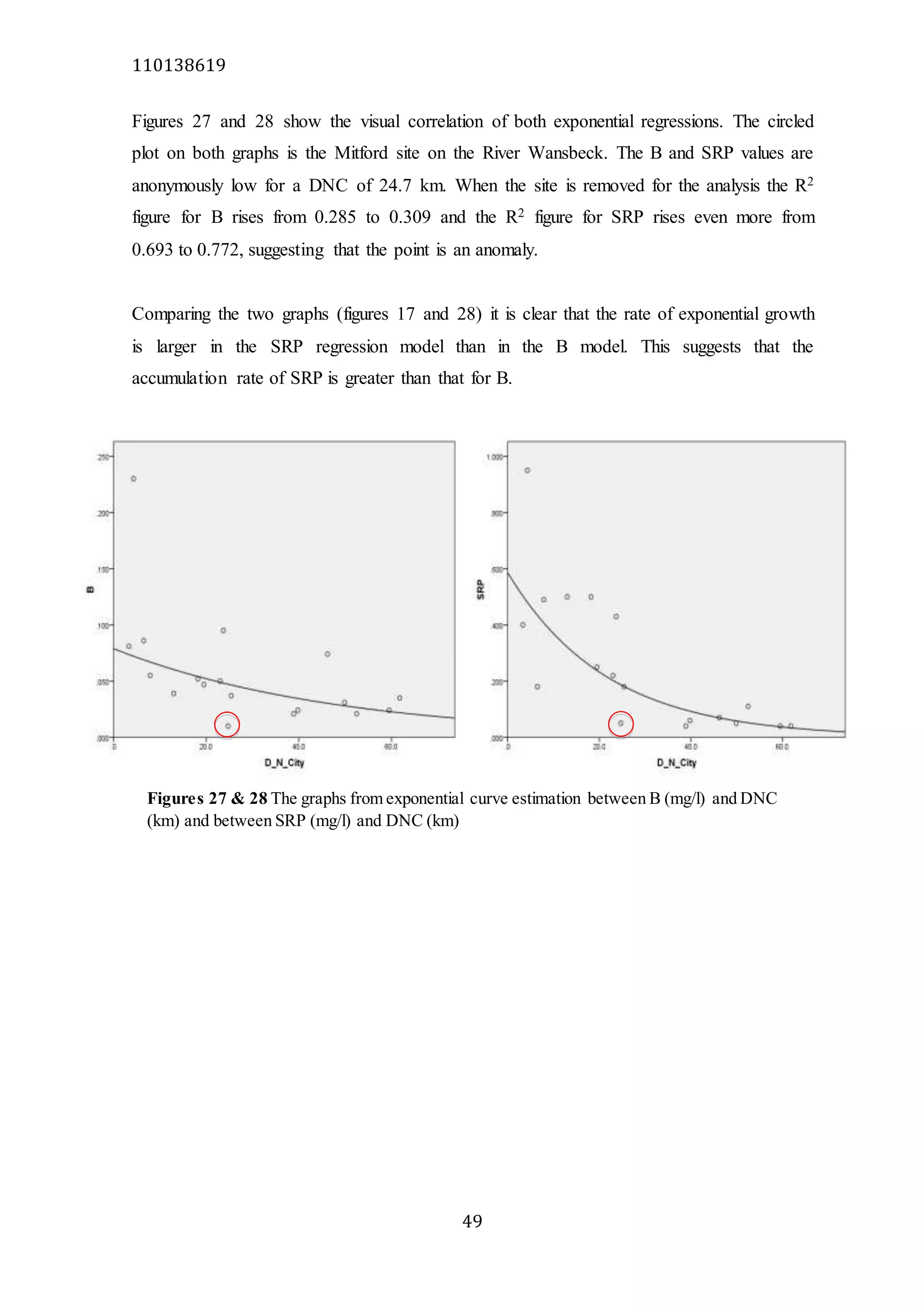

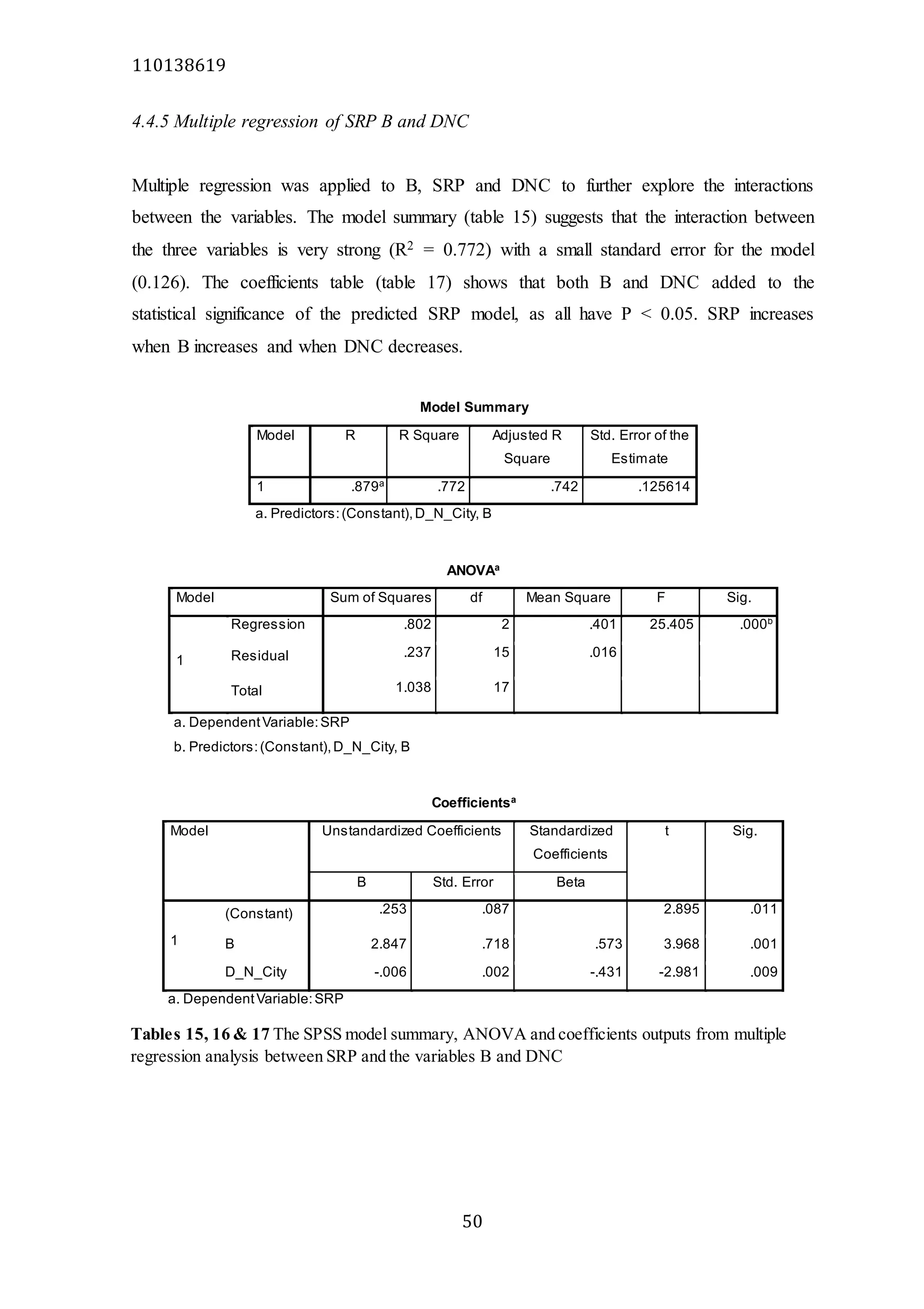

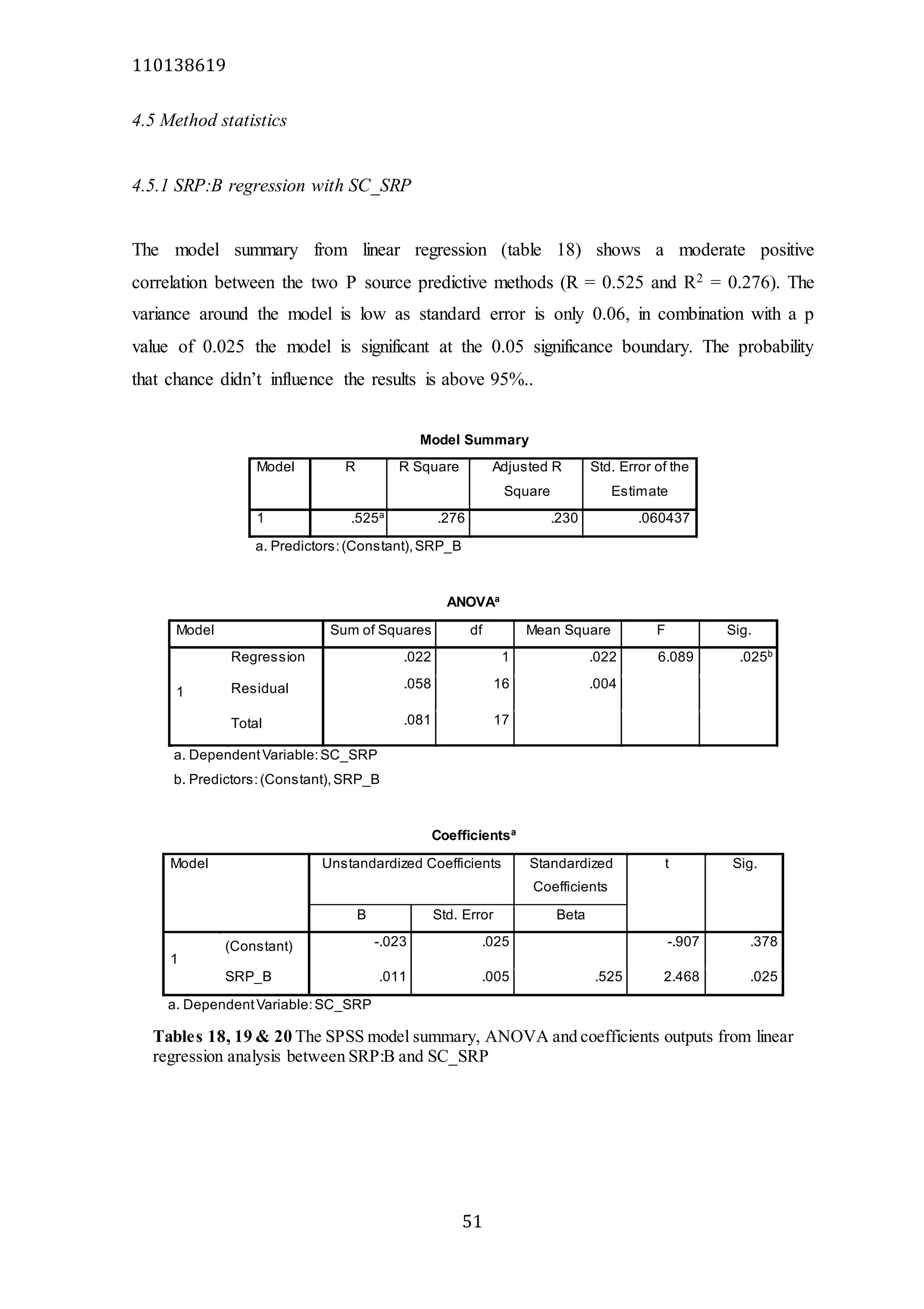

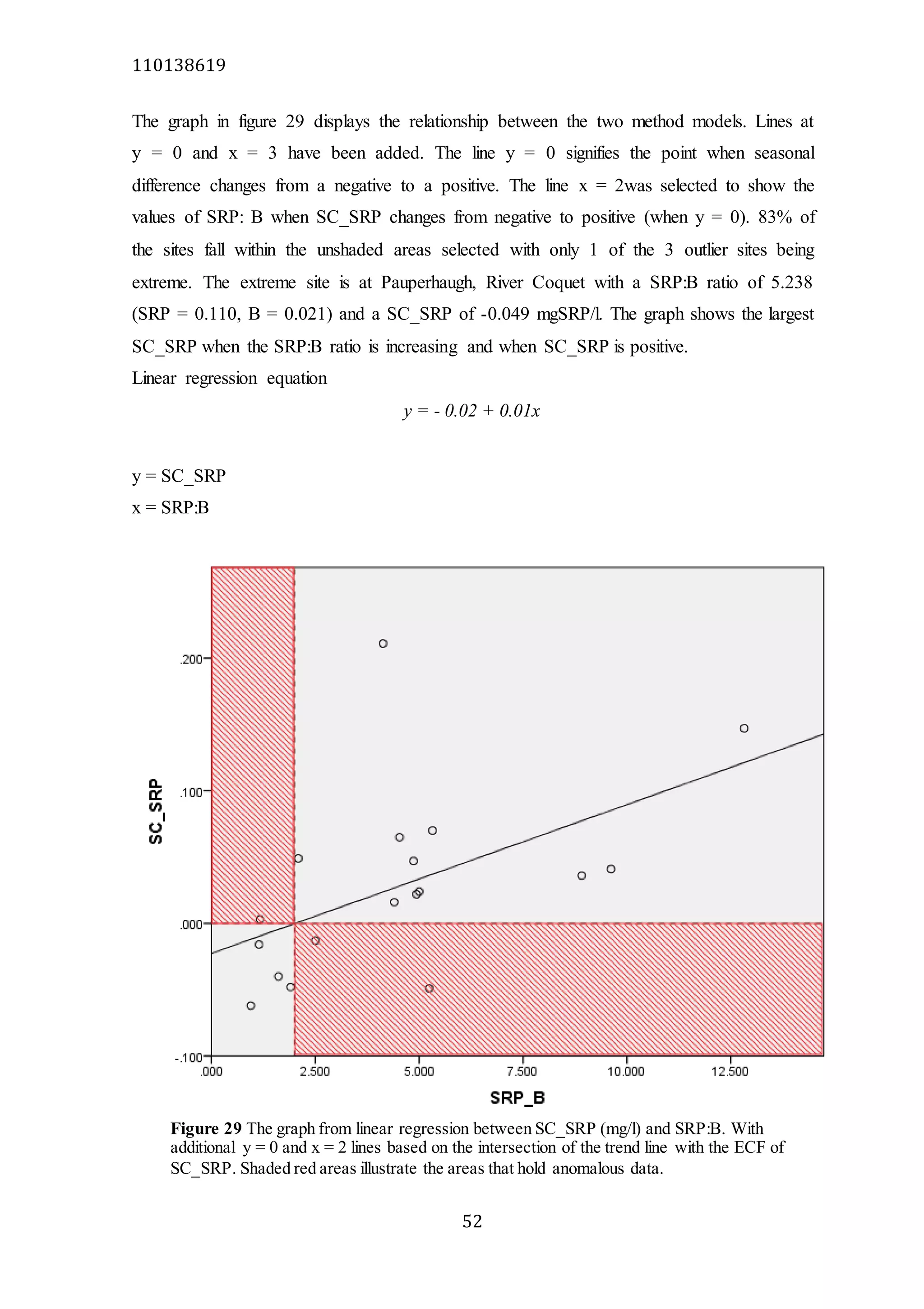

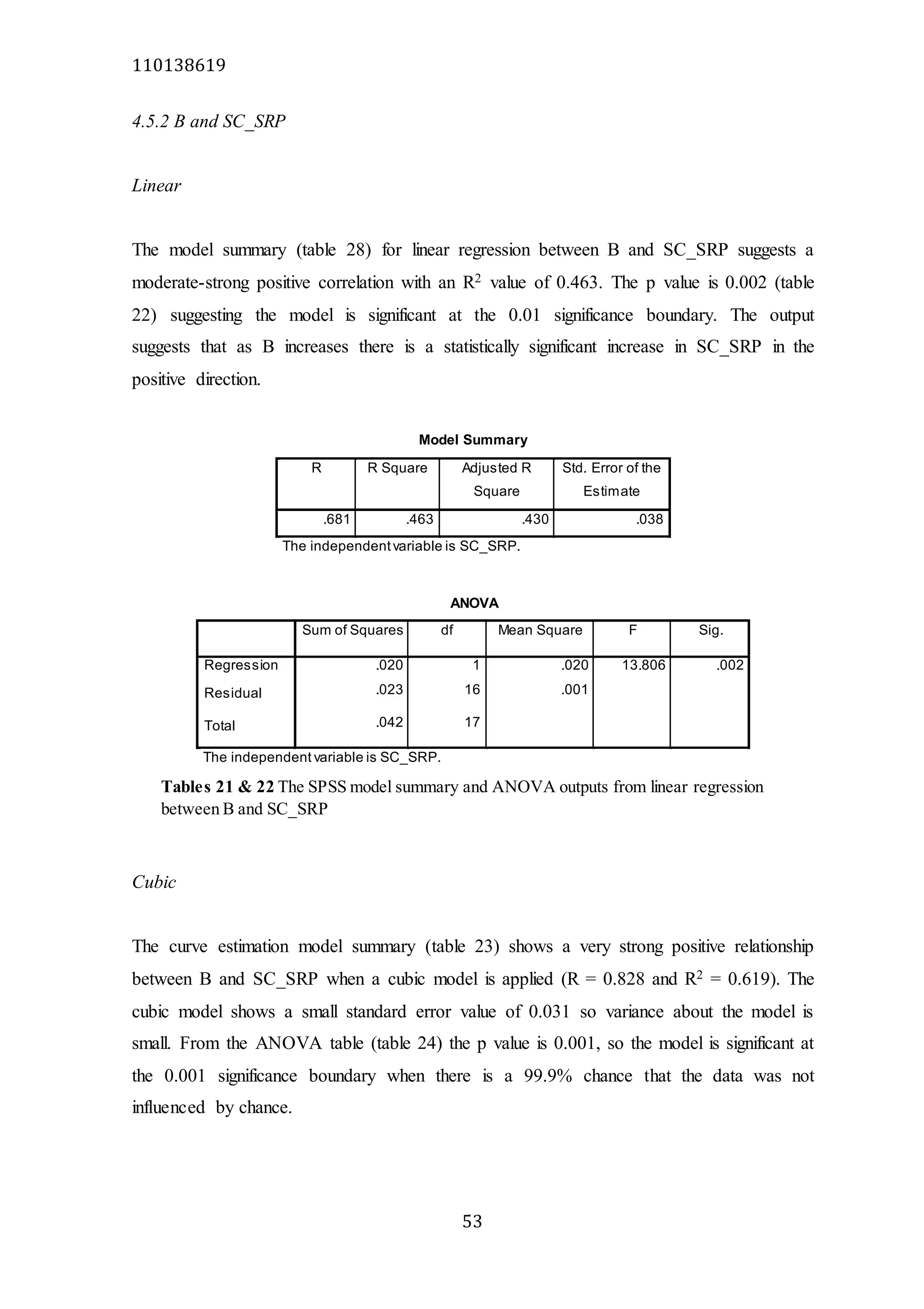

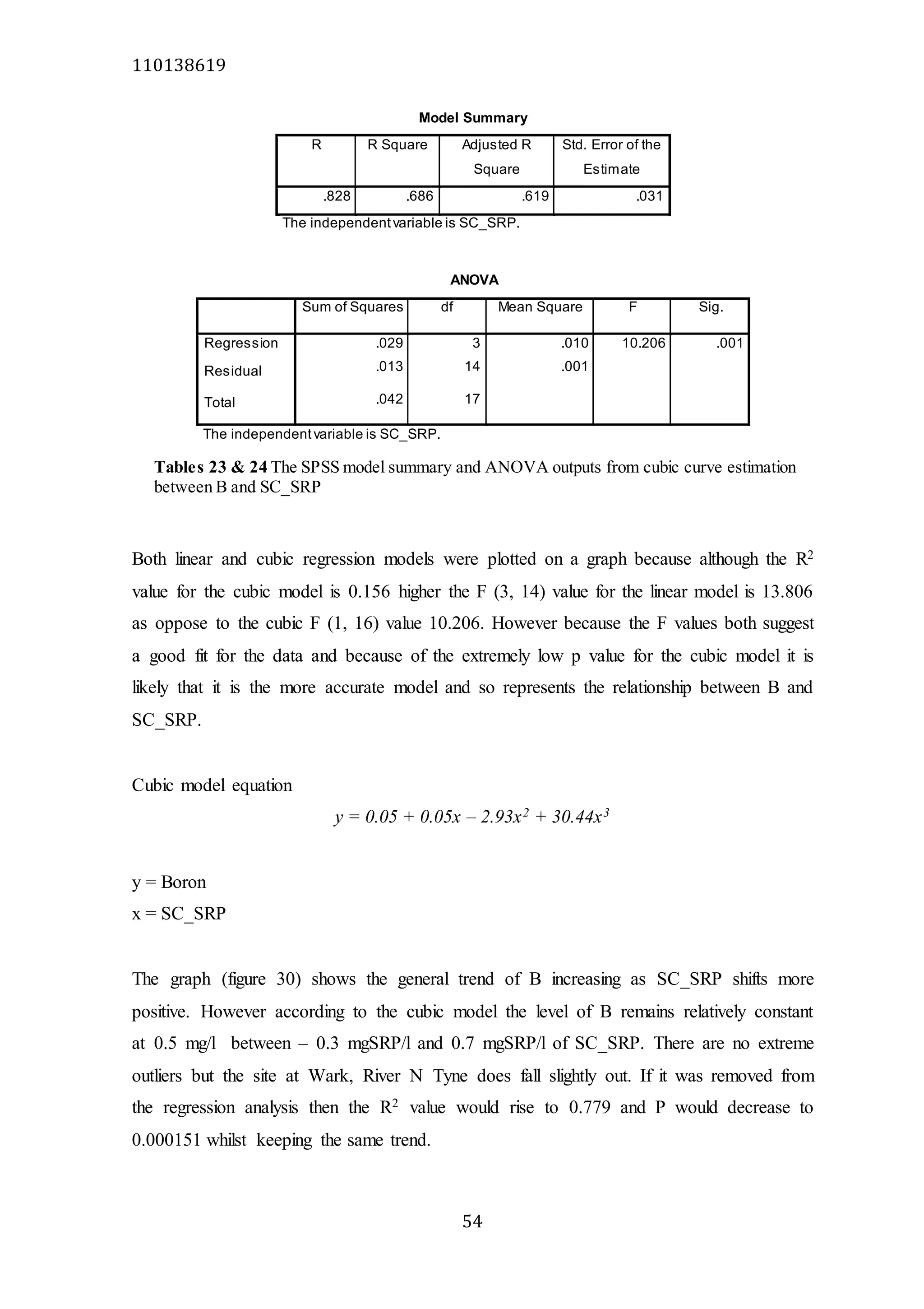

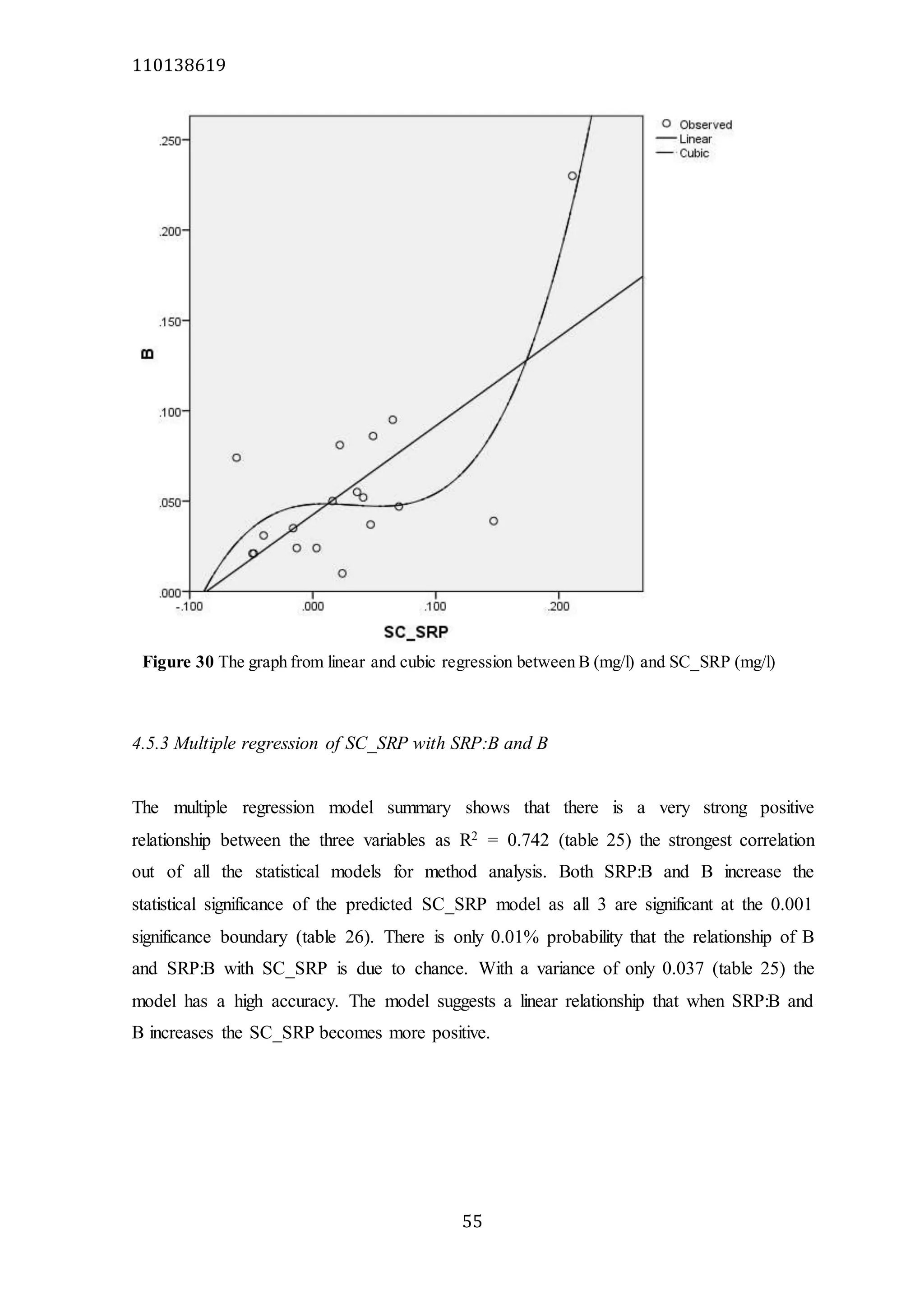

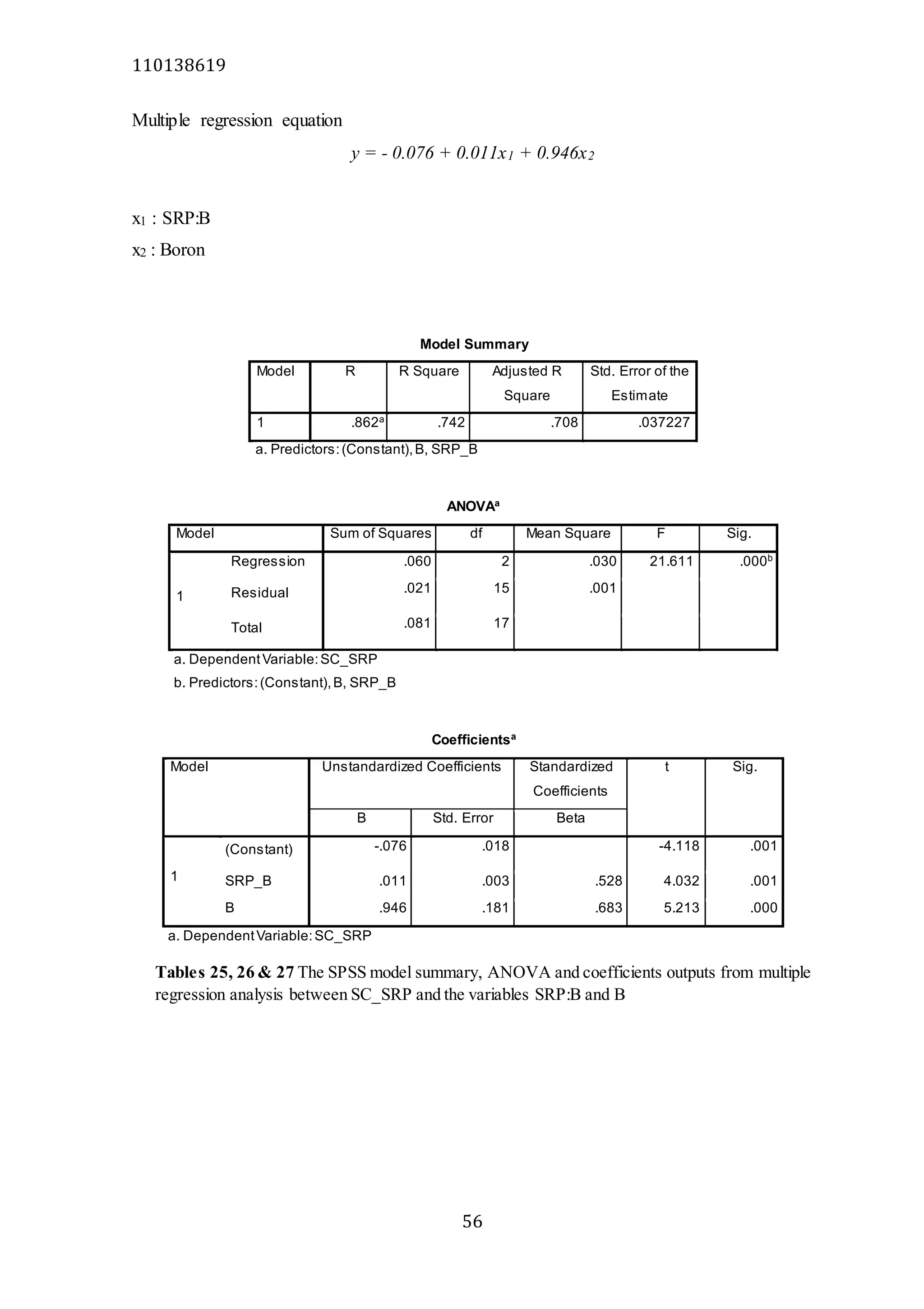

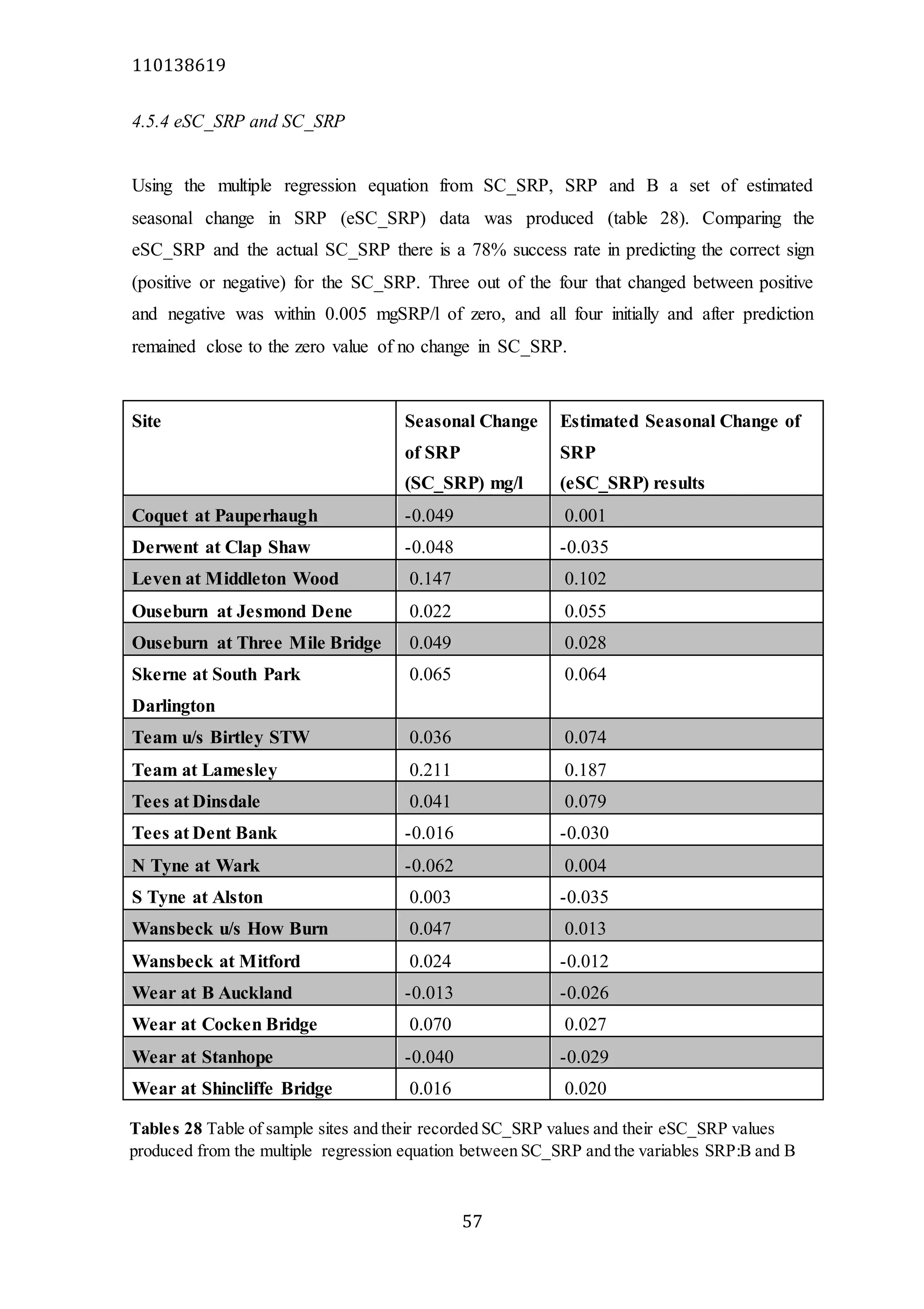

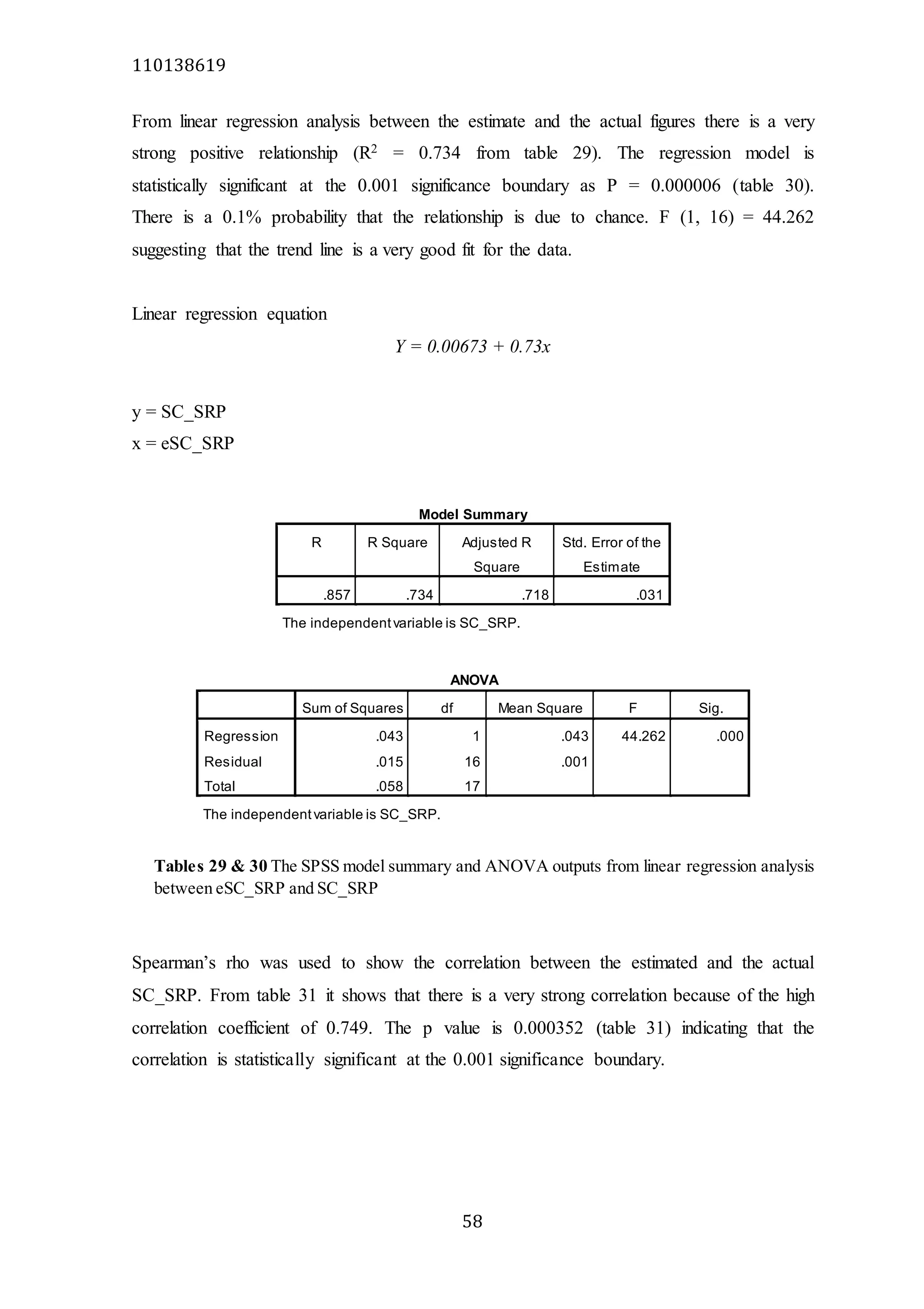

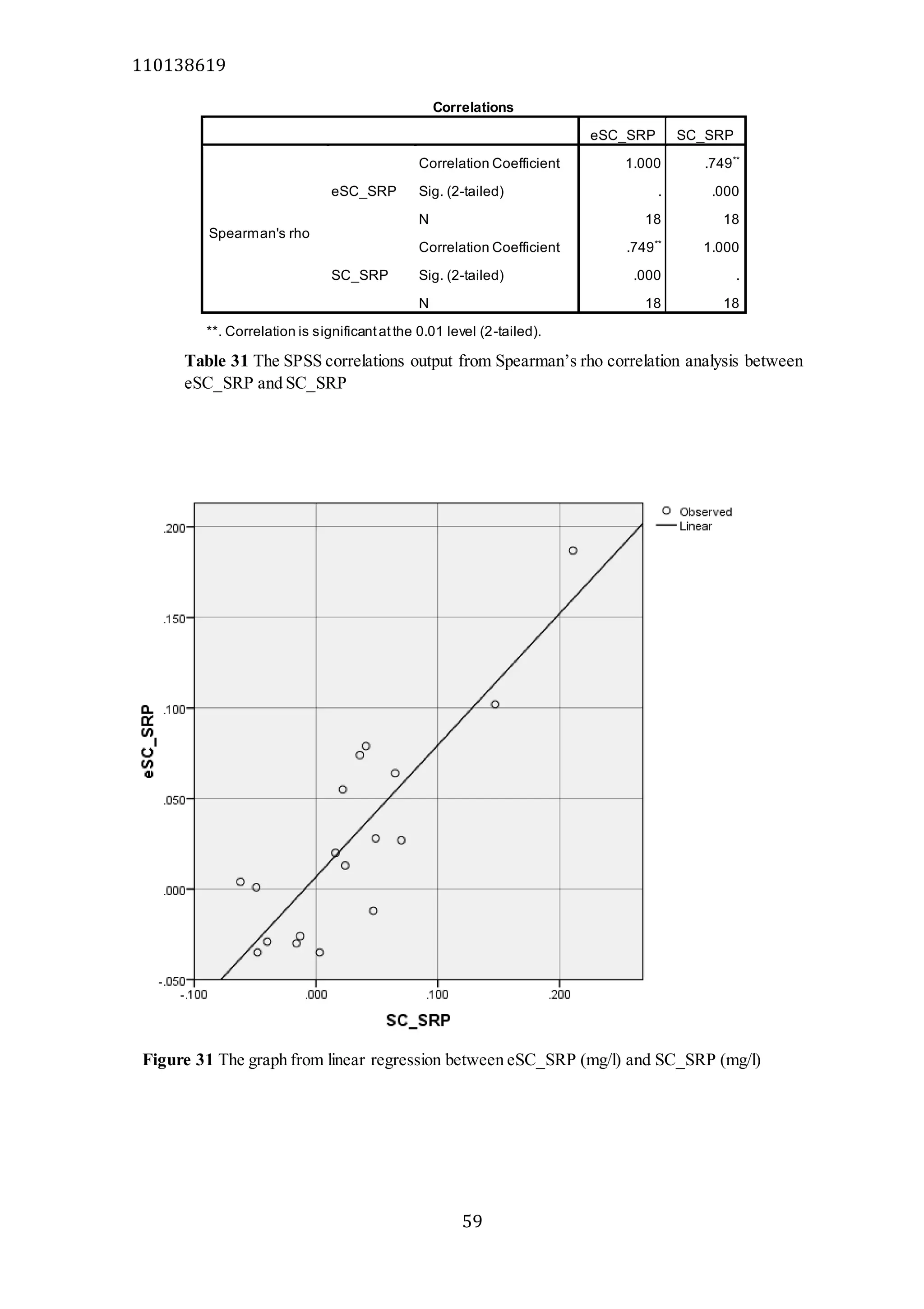

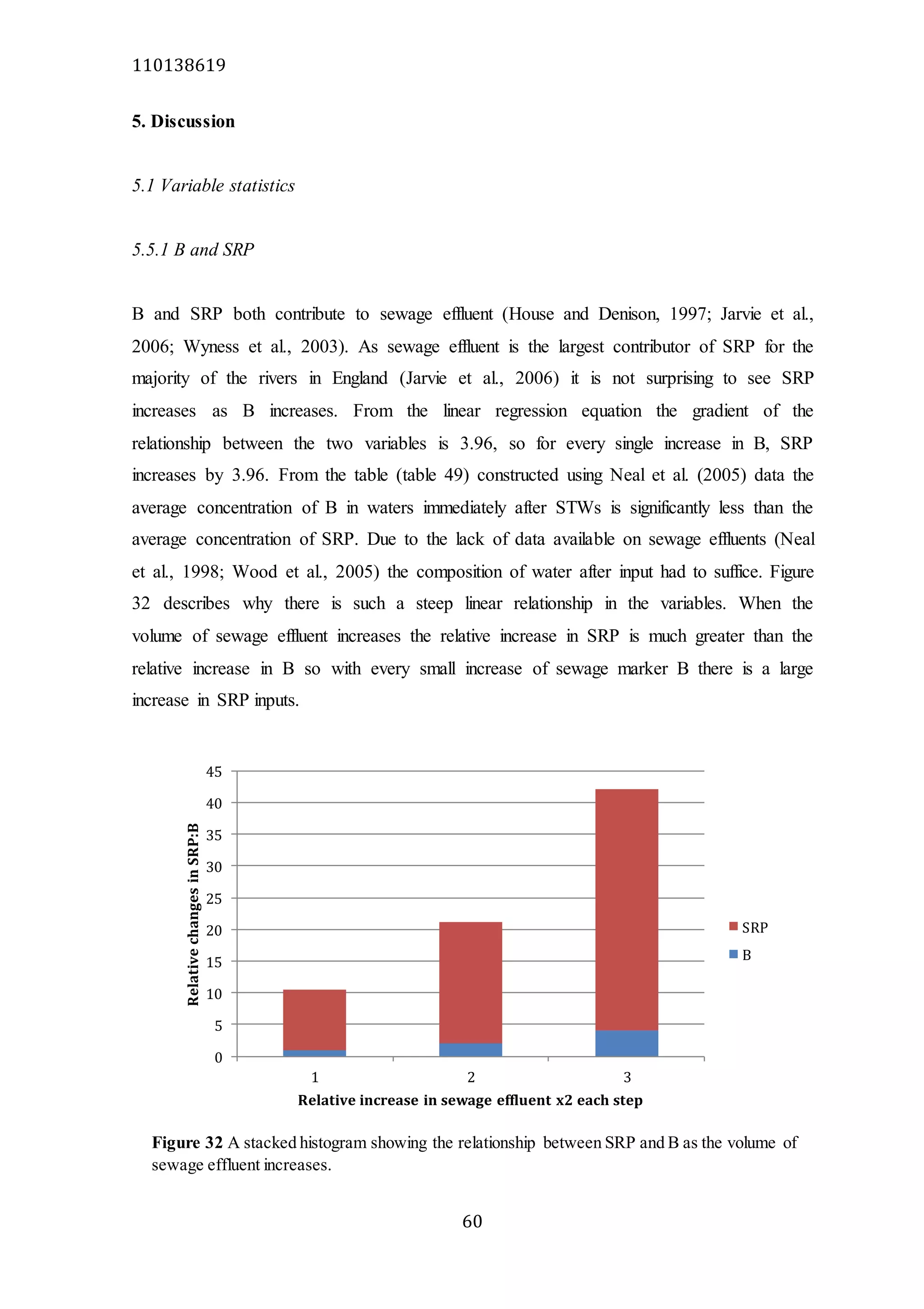

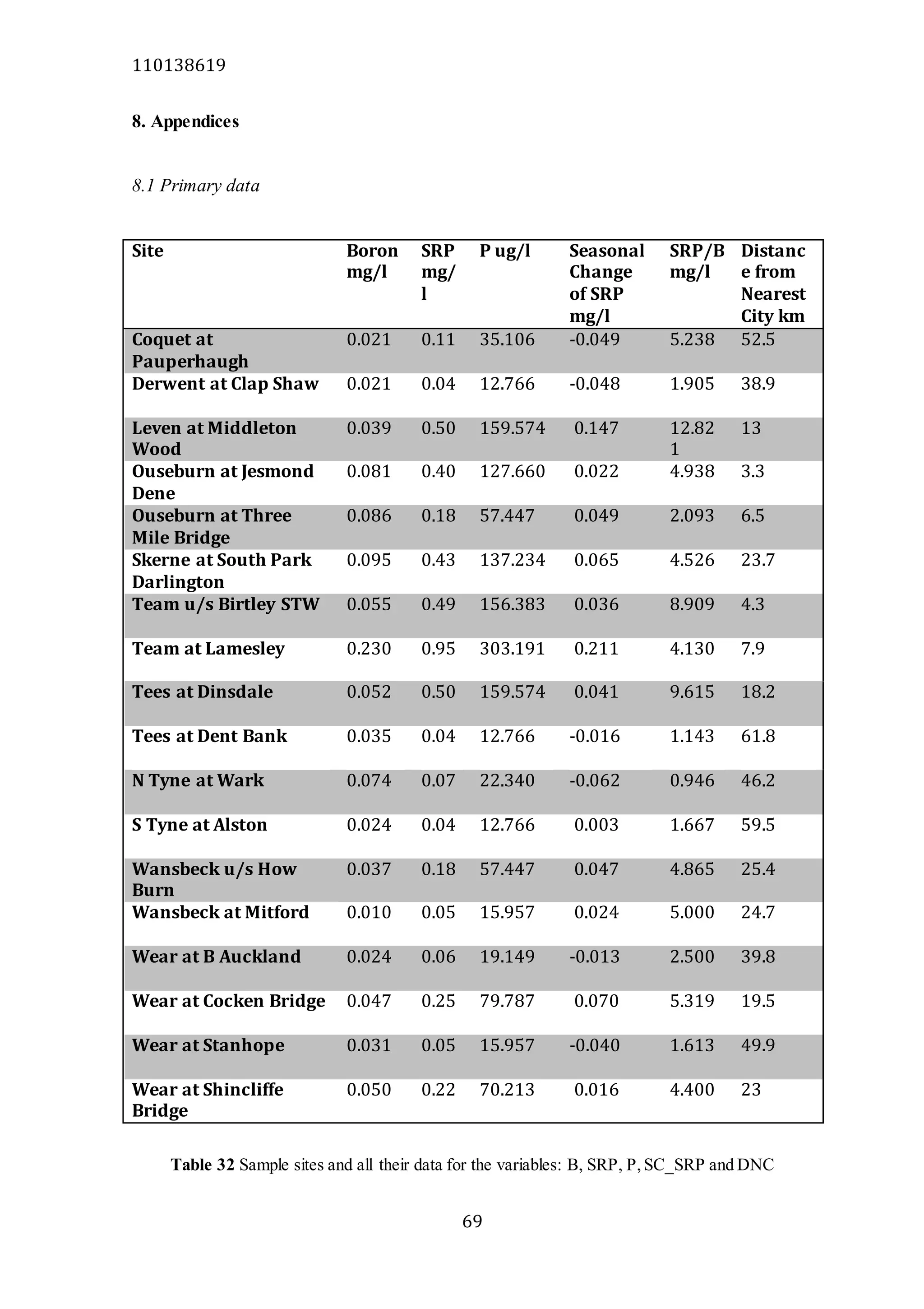

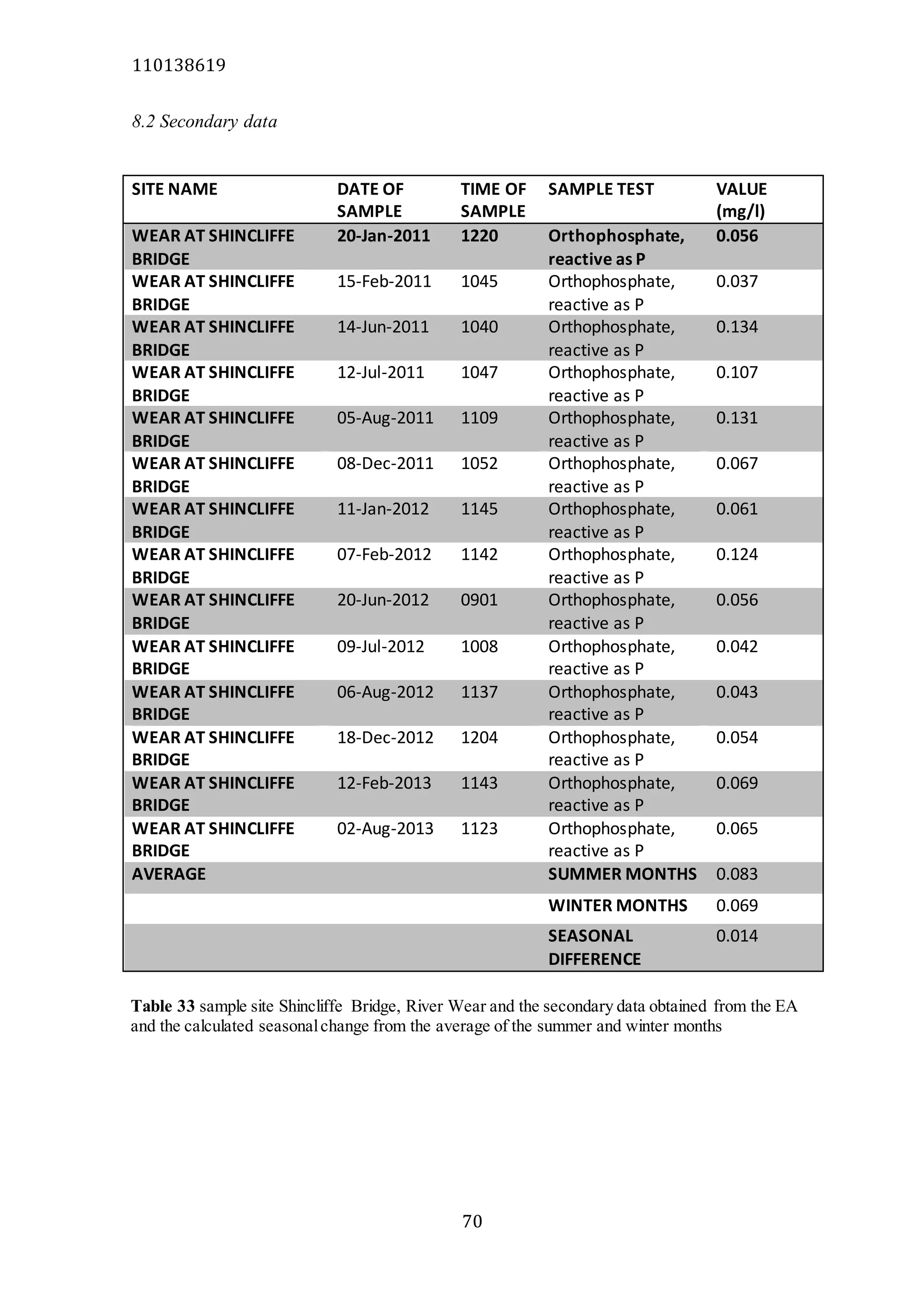

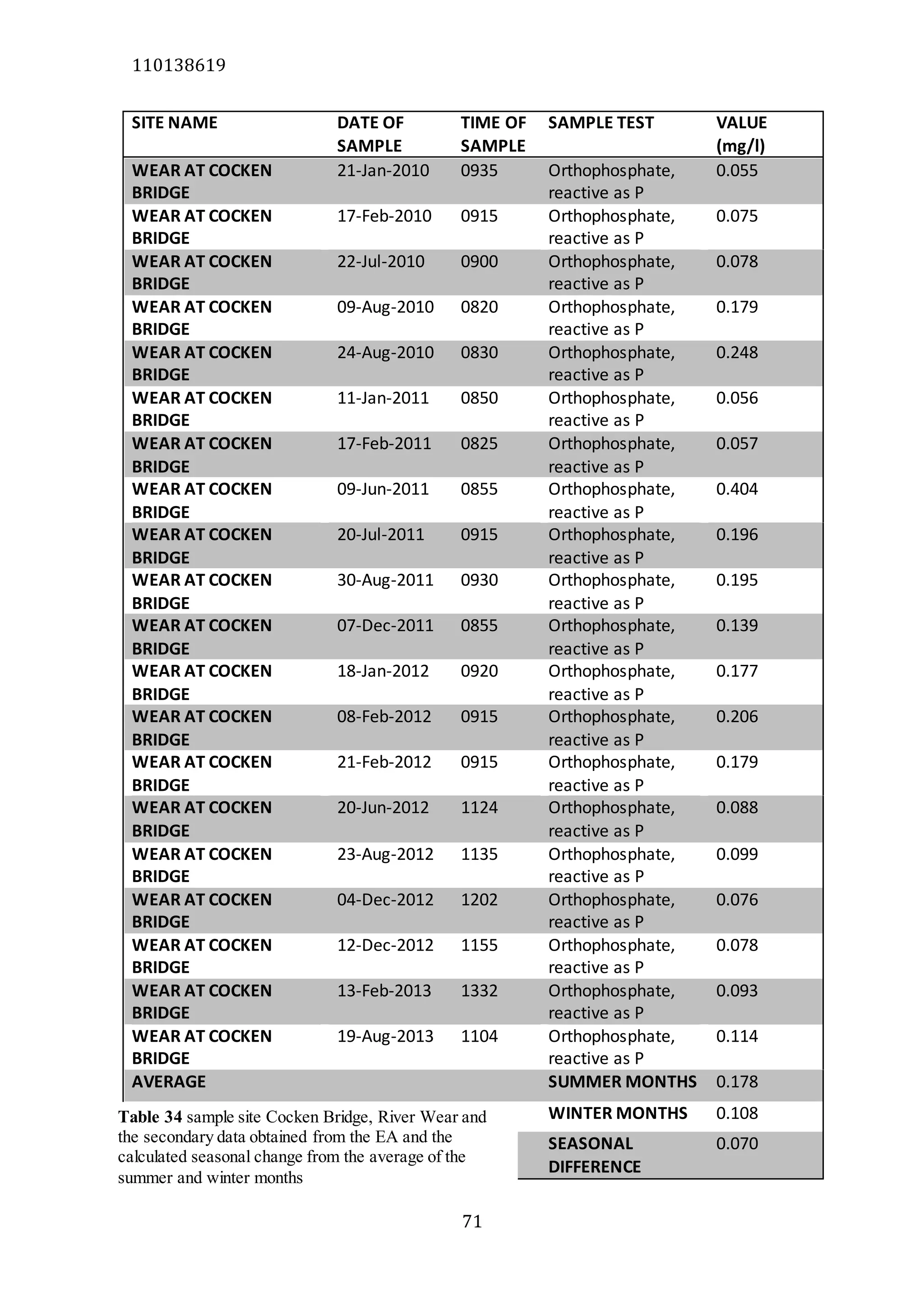

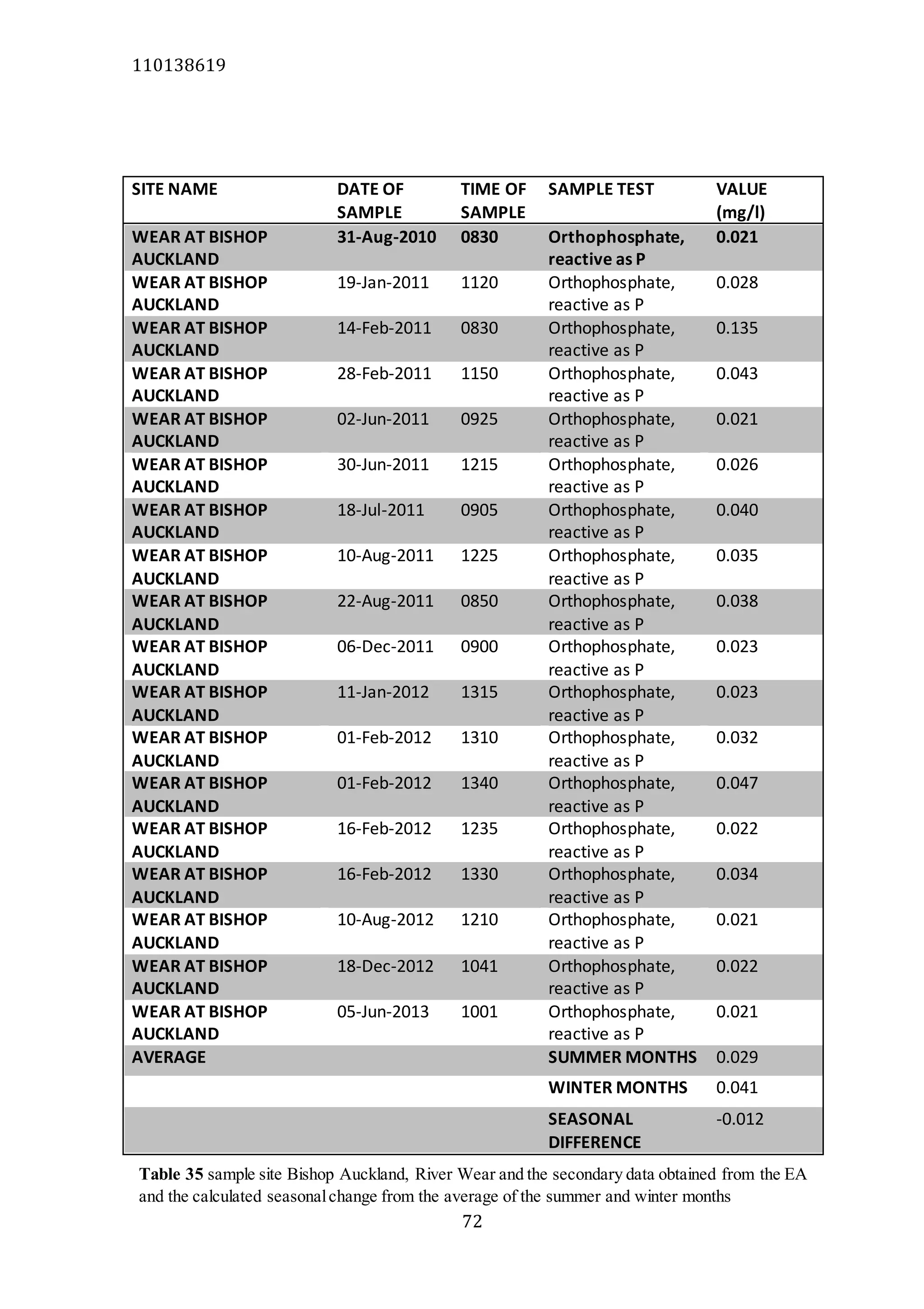

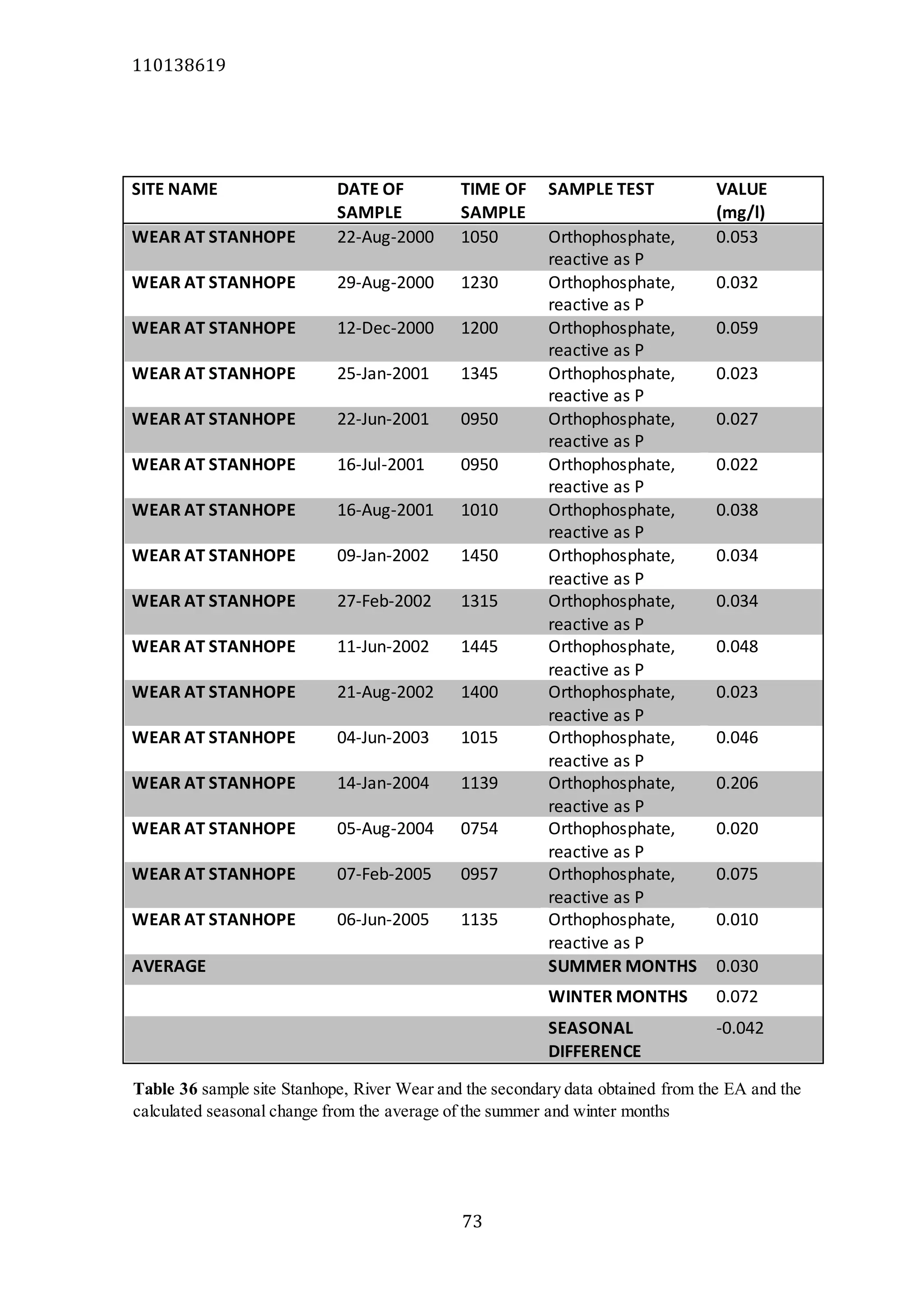

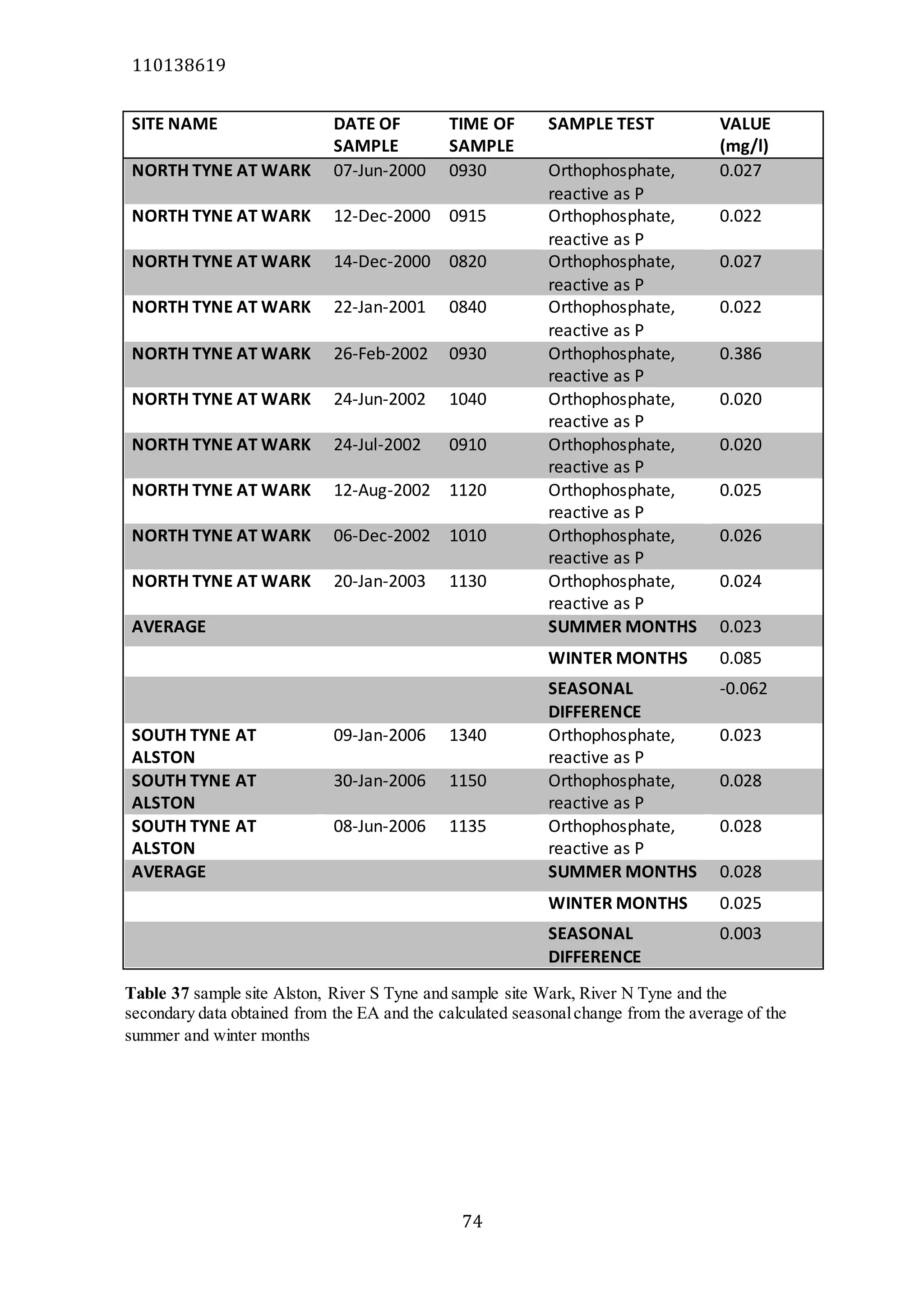

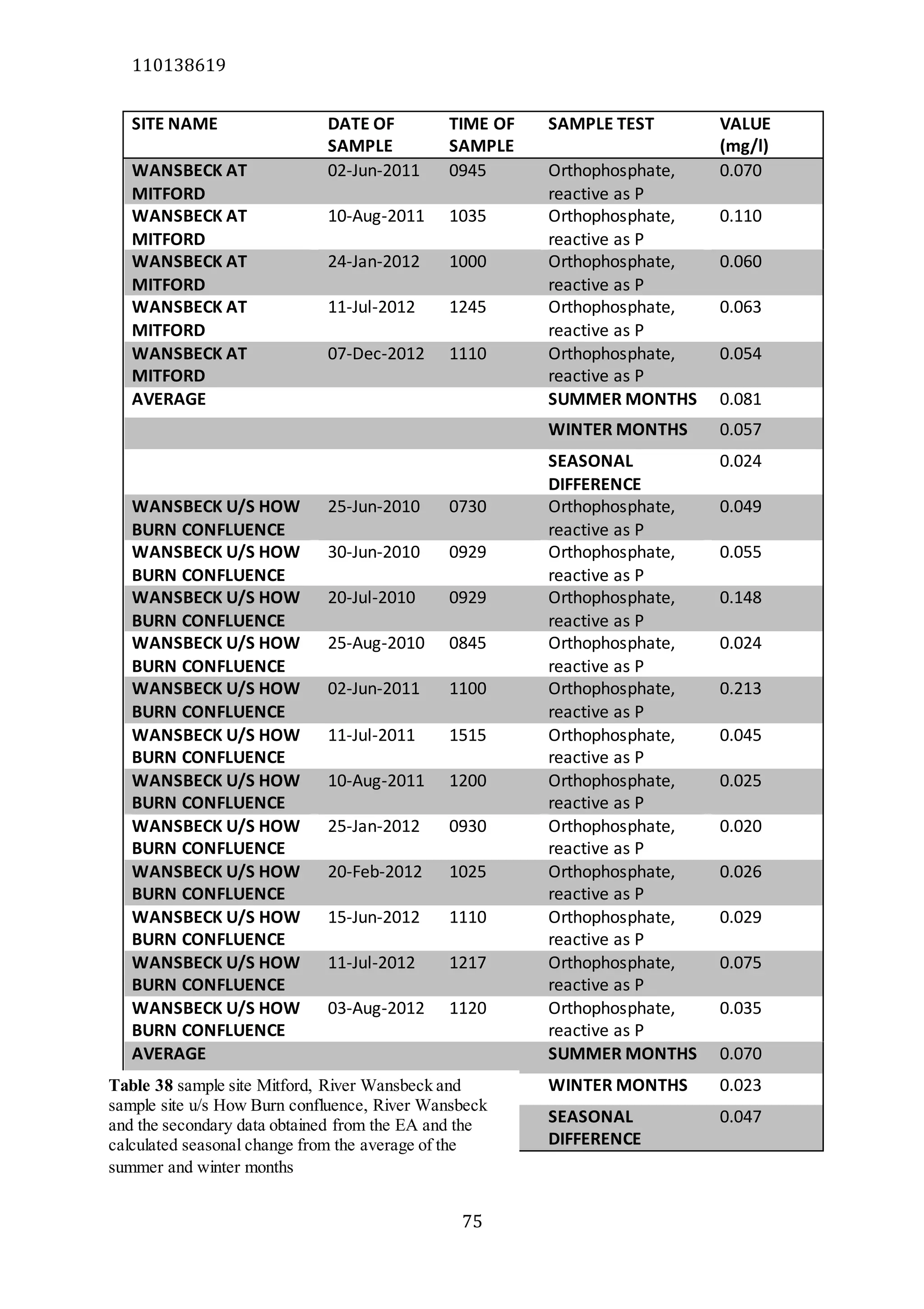

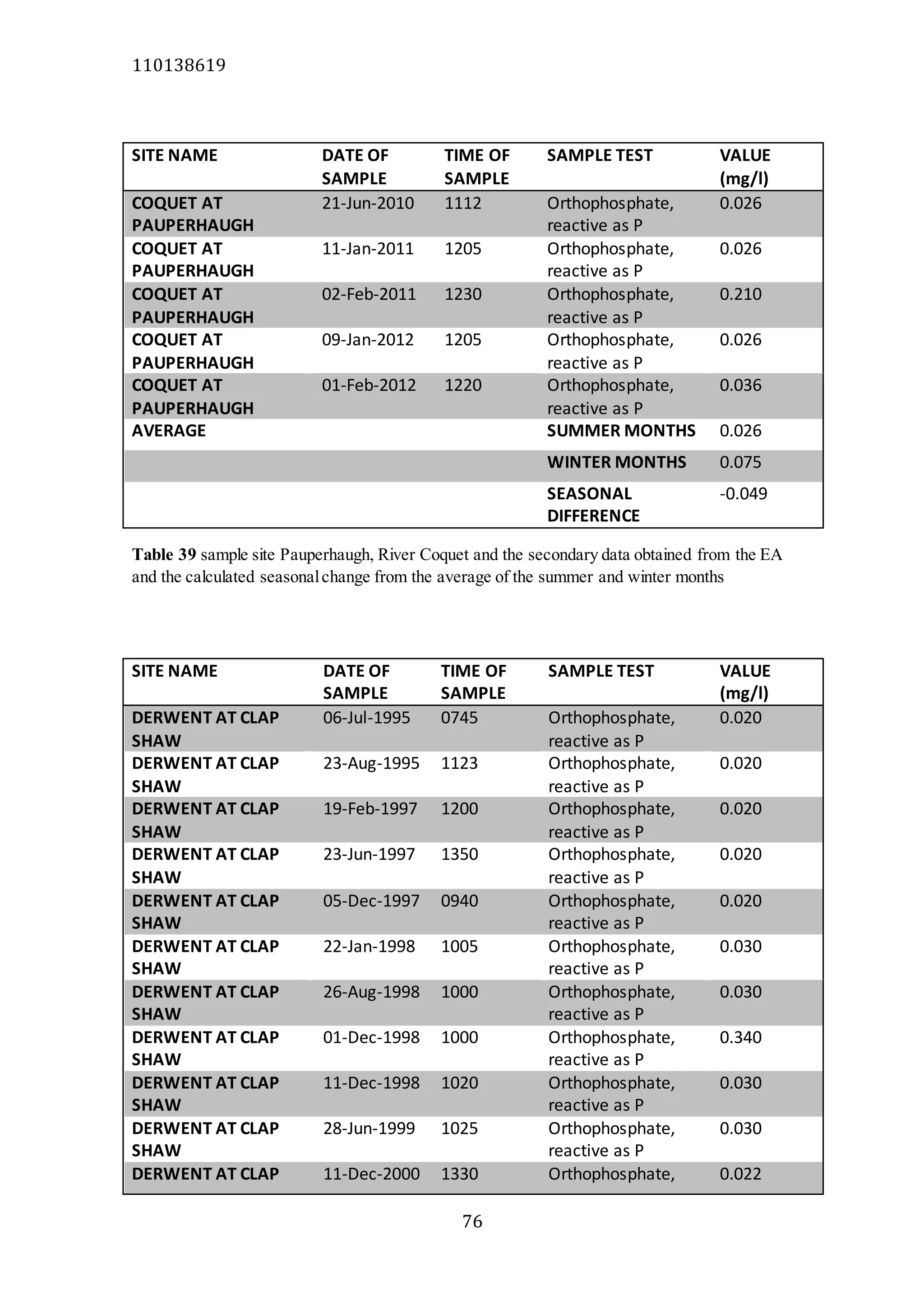

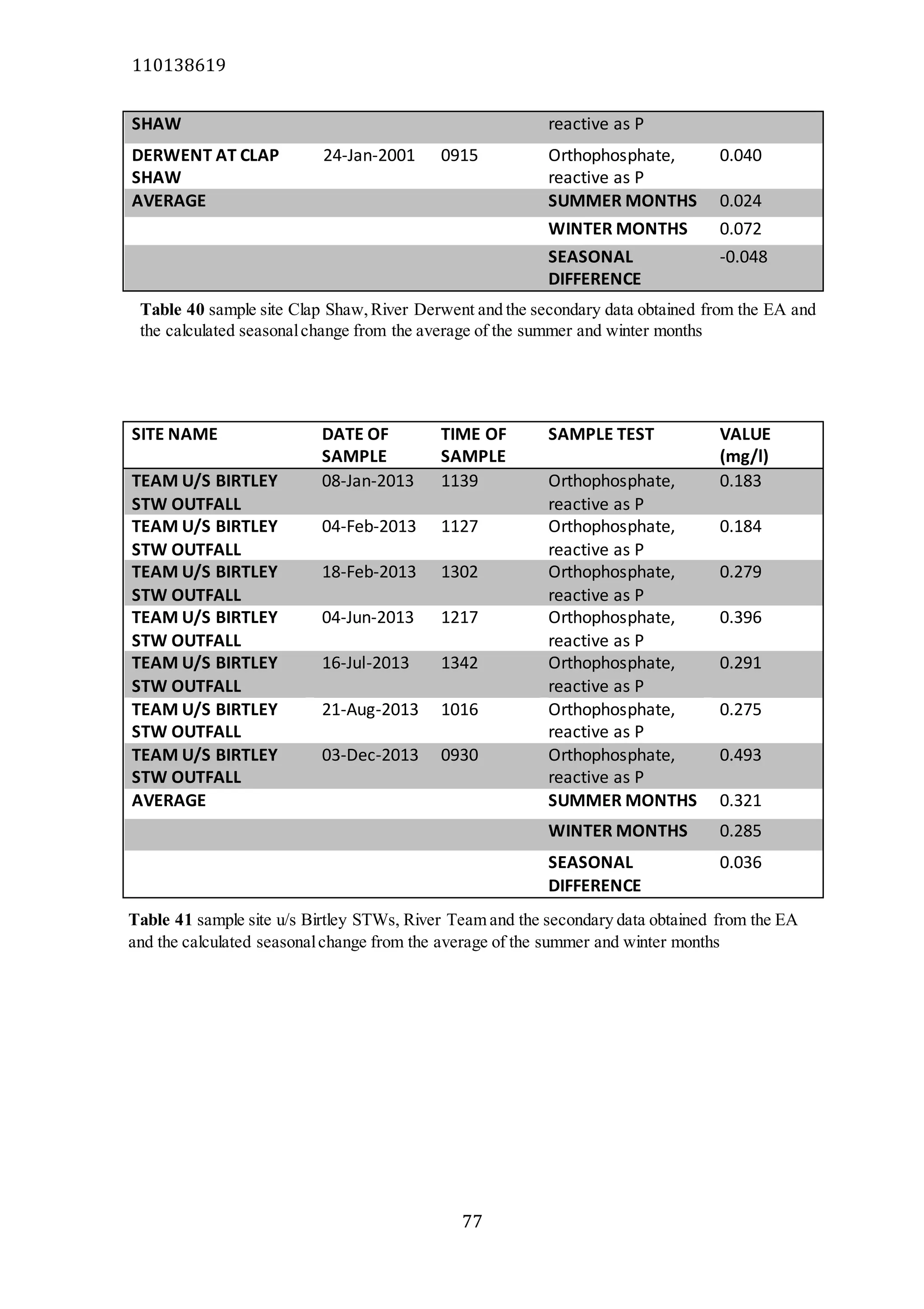

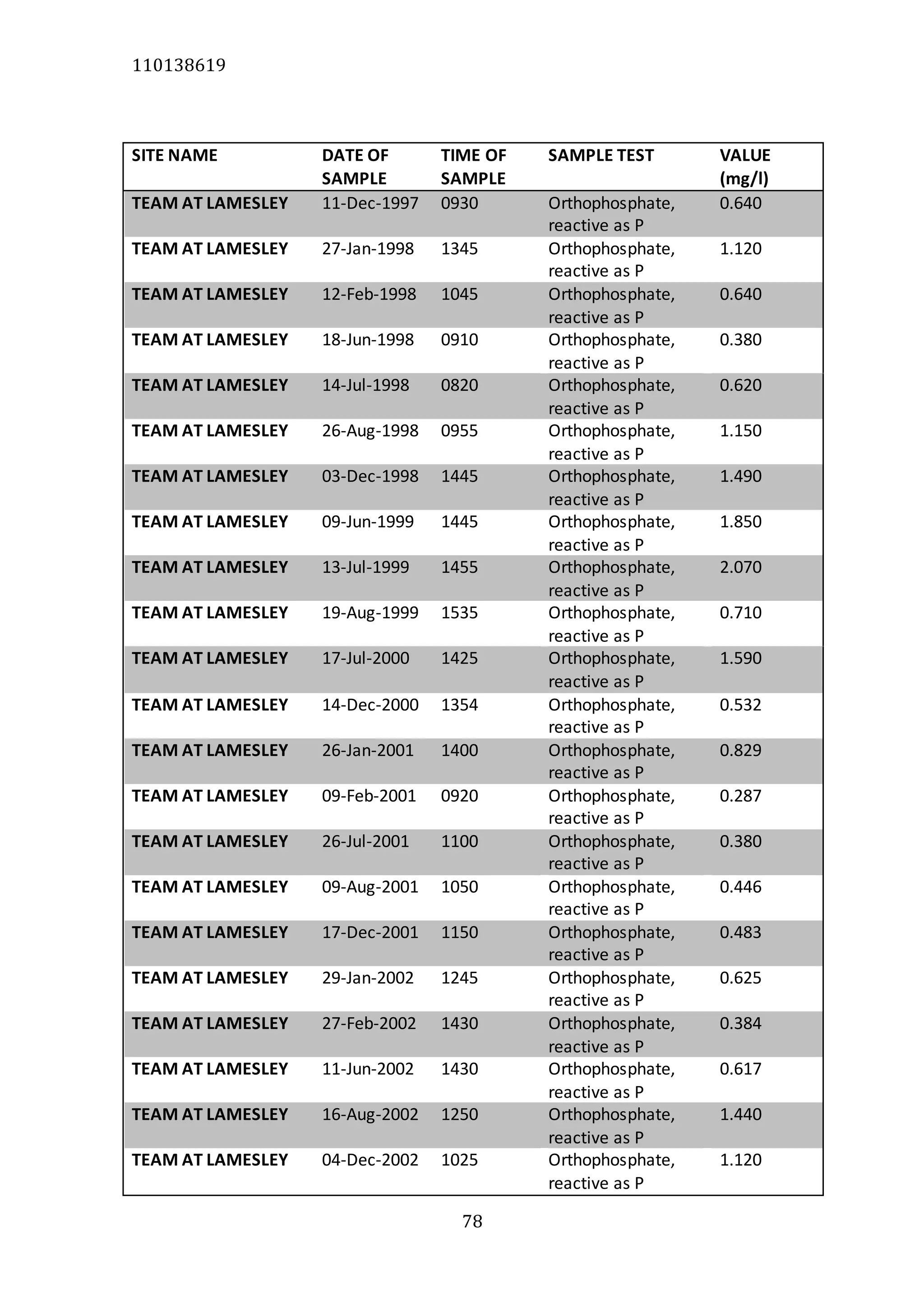

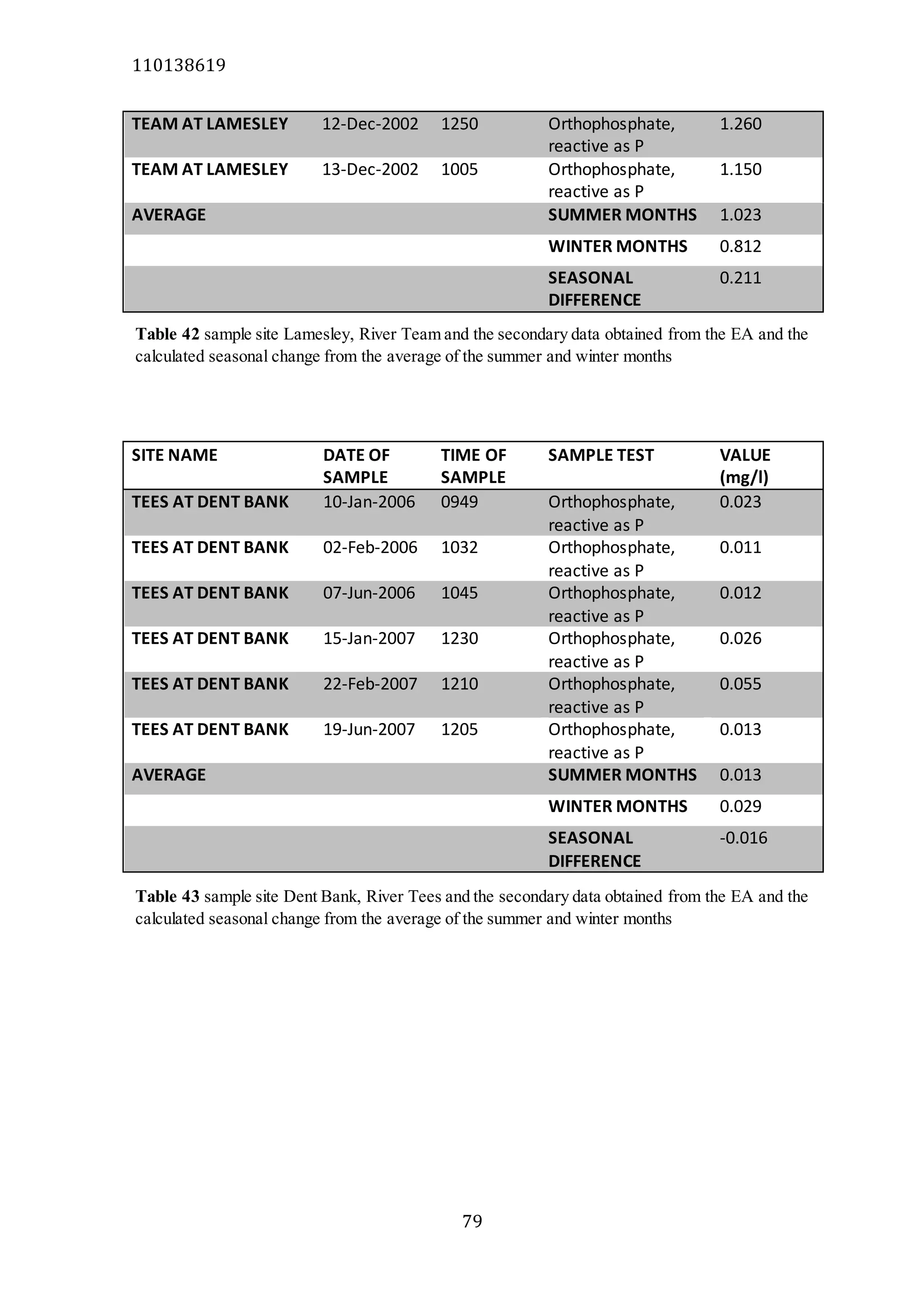

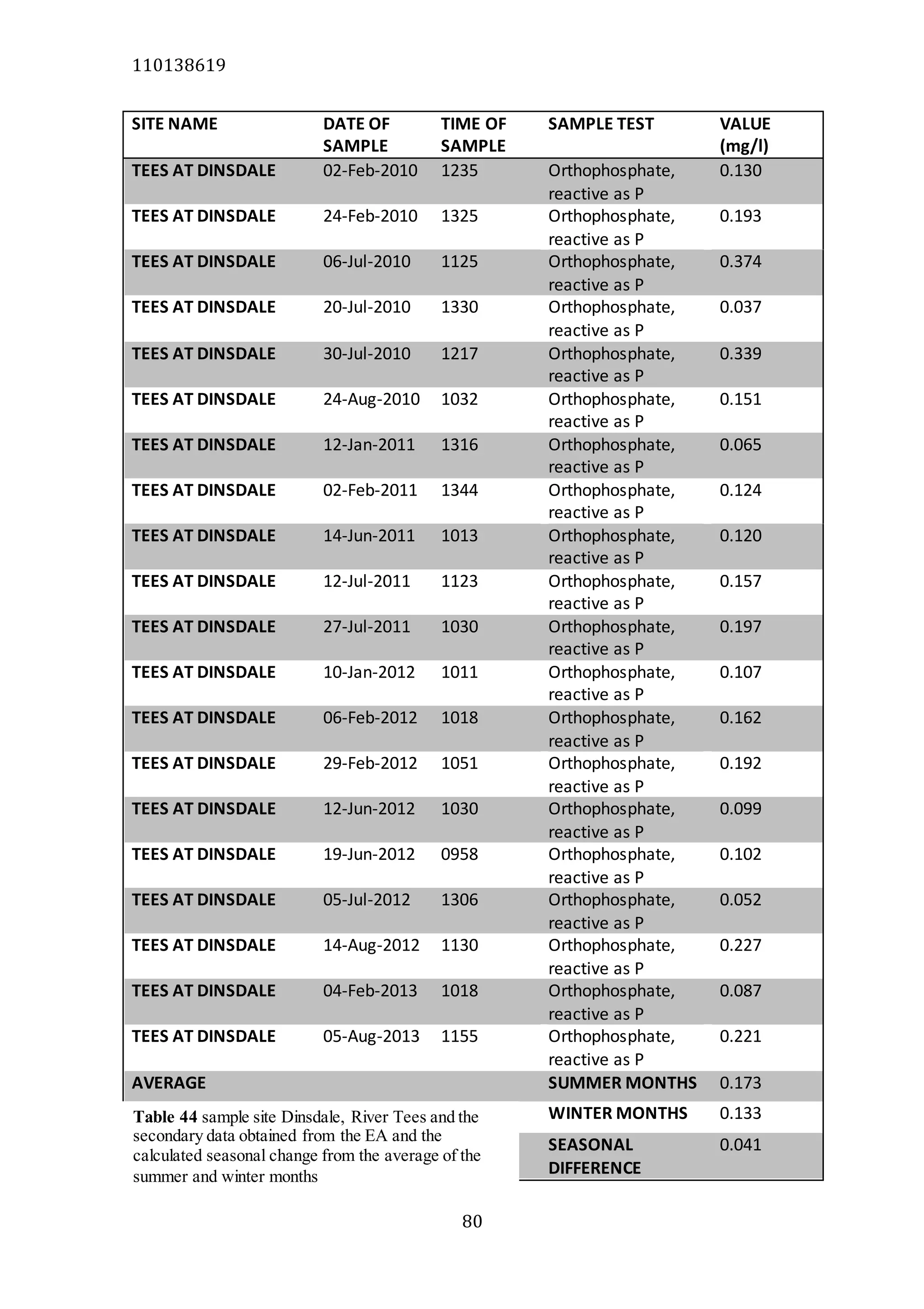

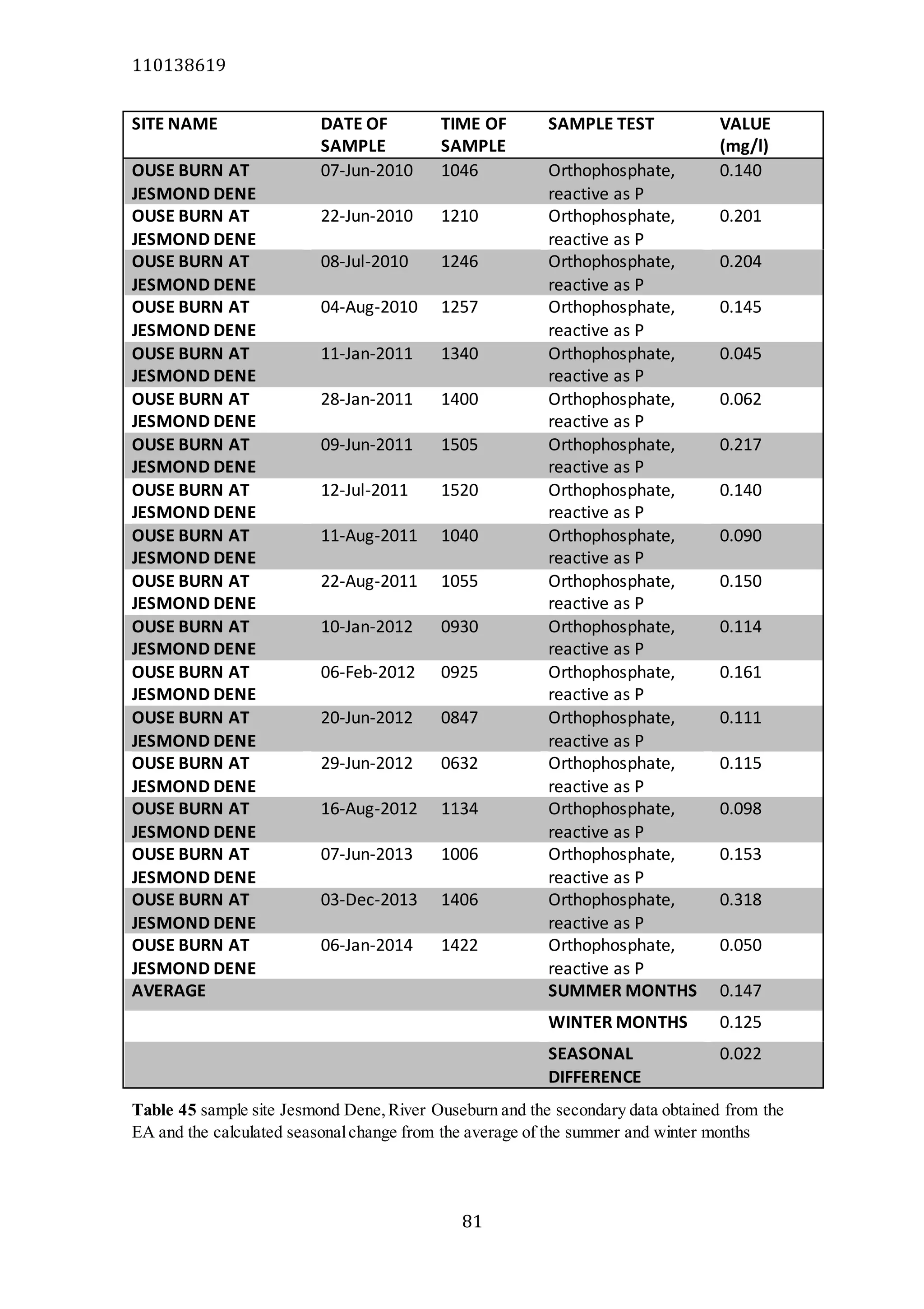

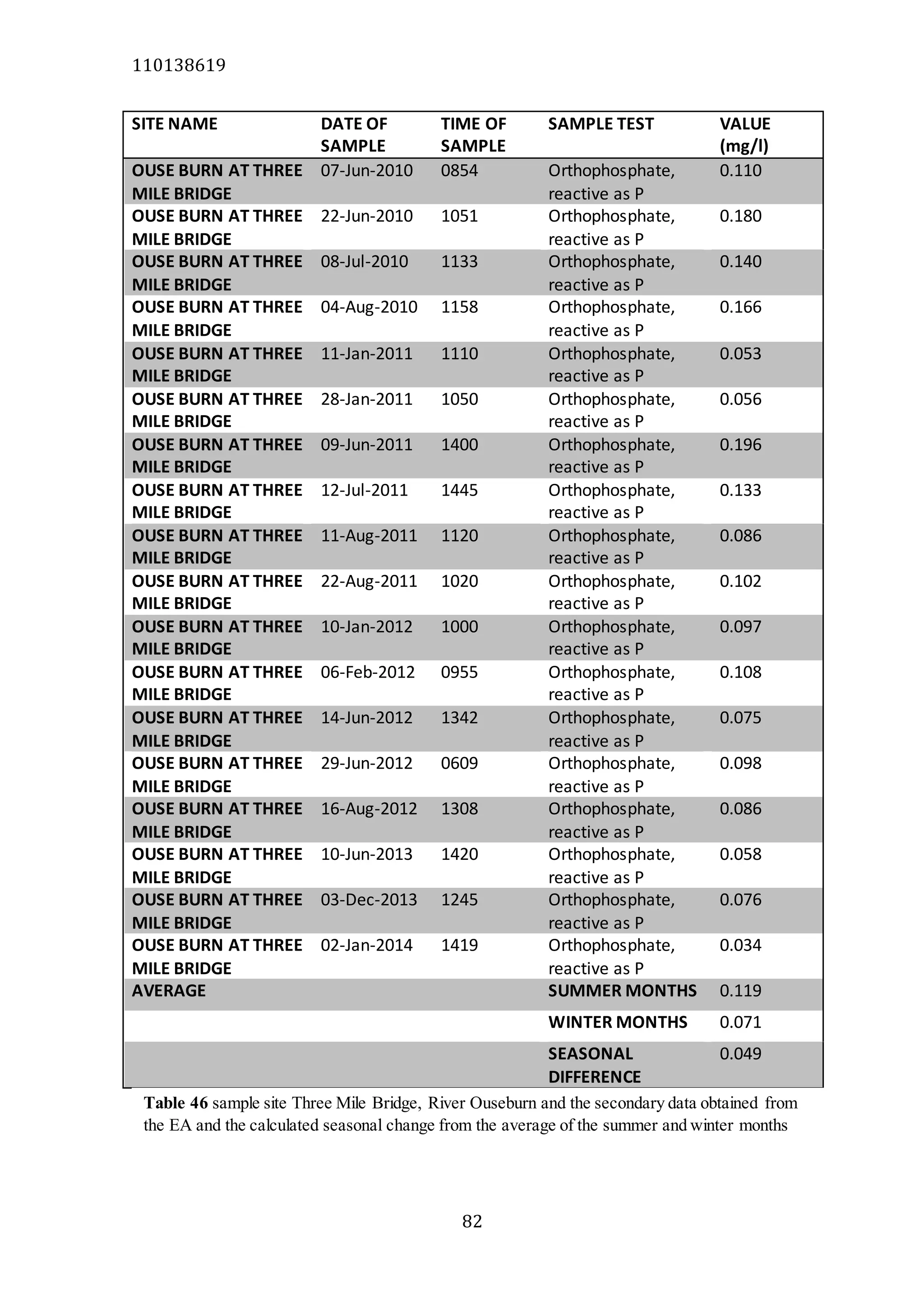

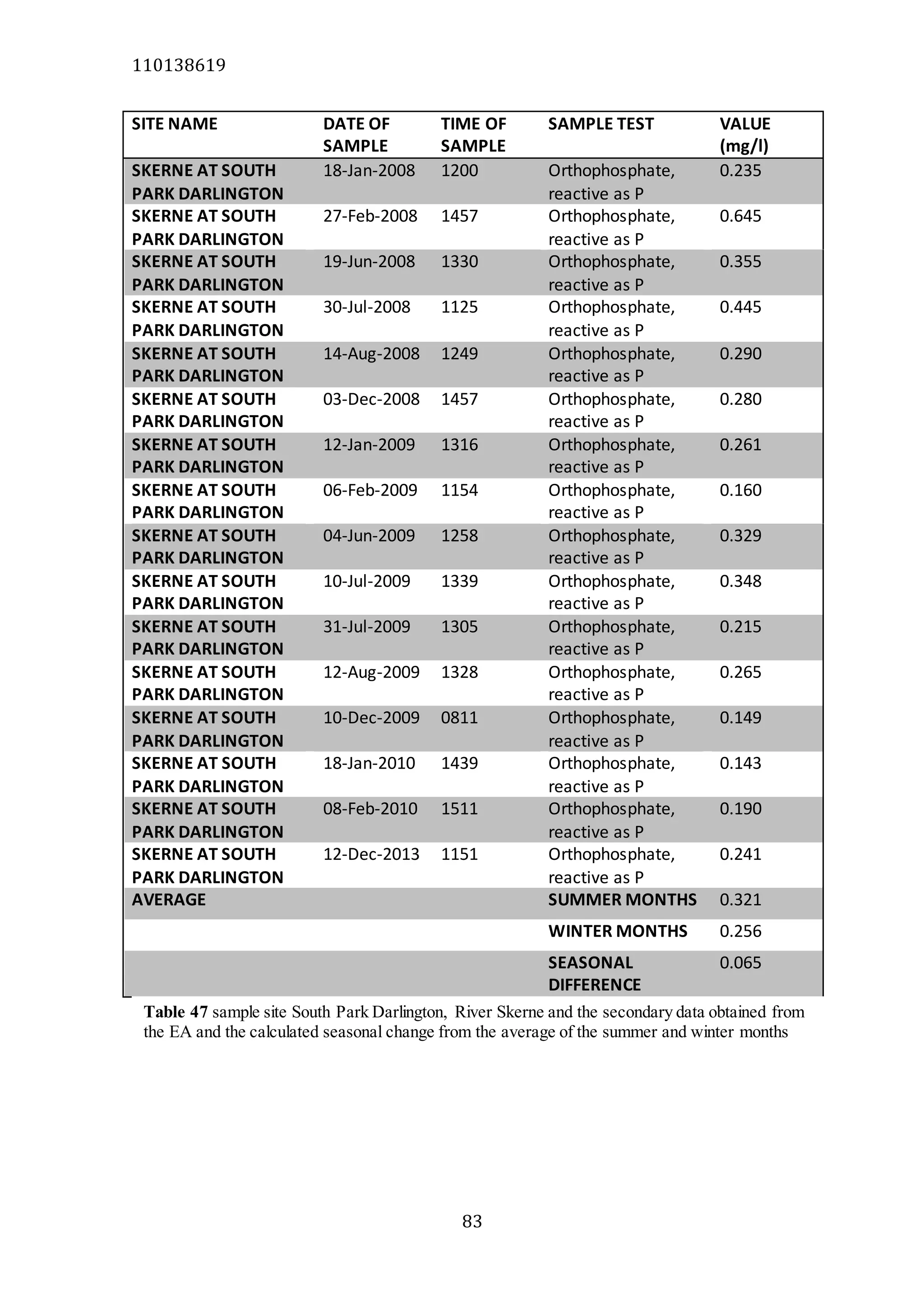

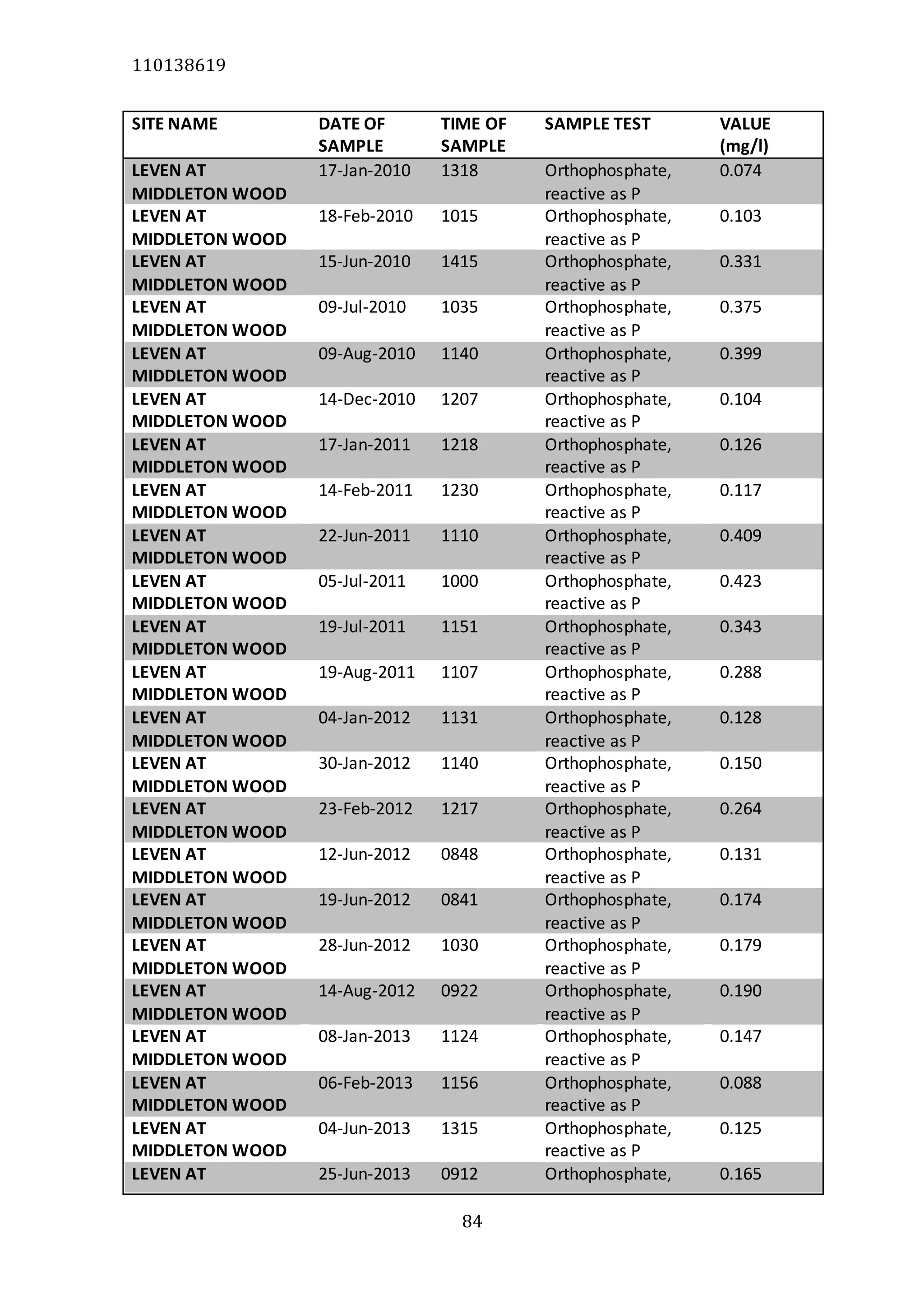

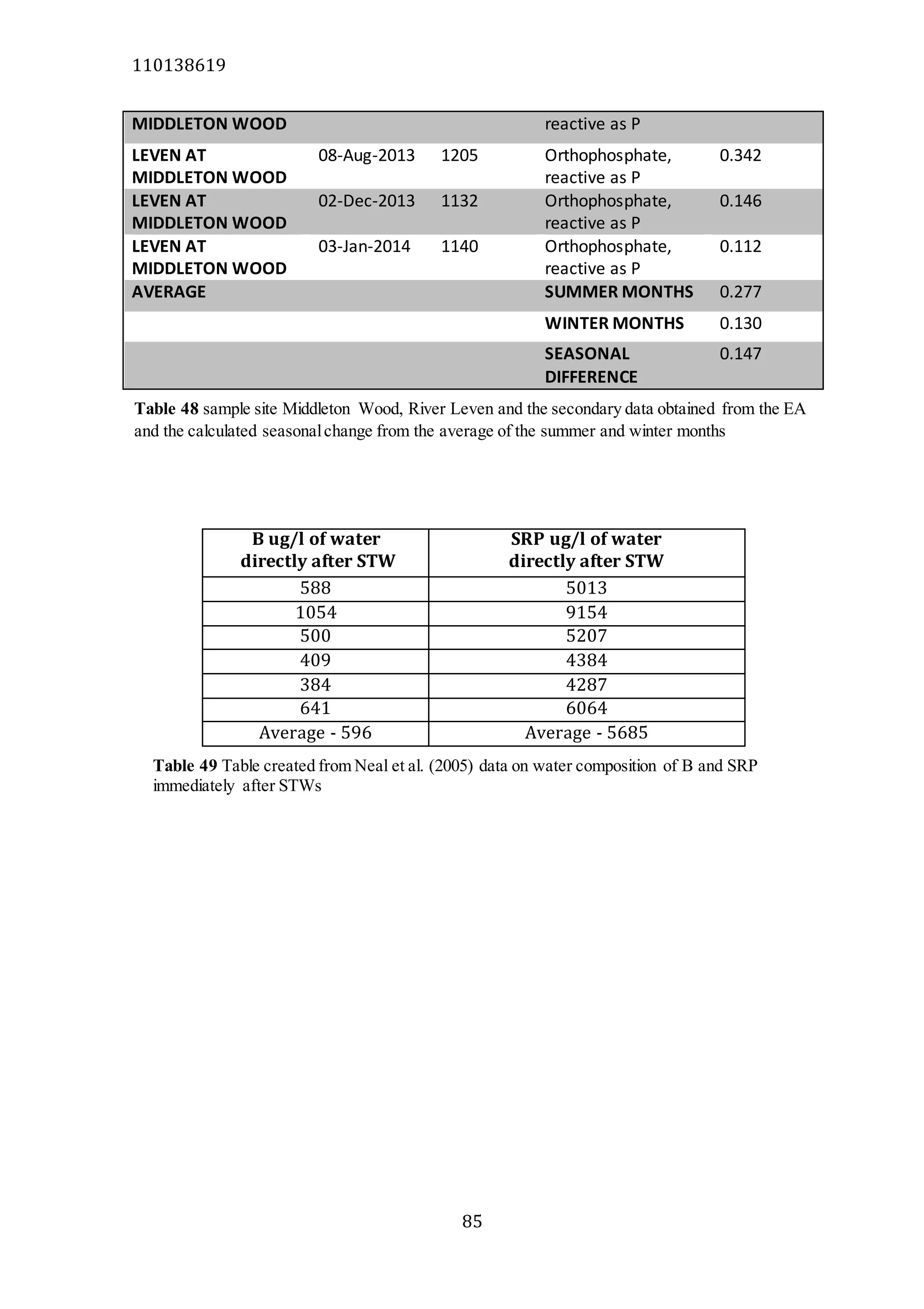

The document analyzes data from 18 sites across 11 rivers in Northumbria to determine relationships between soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP), boron (B), and seasonal change in SRP (SC_SRP) as indicators of phosphorus sources. Statistical analysis found significant positive relationships between SRP and B, and SRP and SC_SRP. B and distance from cities were negatively correlated, as were SRP and distance. Regression analysis showed a moderate correlation between SRP:B ratio and SC_SRP. Estimated SC_SRP values from regression of SRP and B matched actual SC_SRP values significantly. The results support using the SRP, B, and SC_SRP analysis to determine dominant phosphorus sources as required