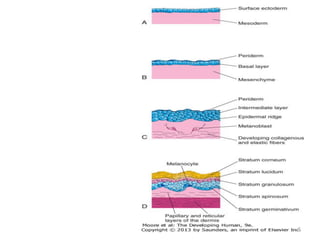

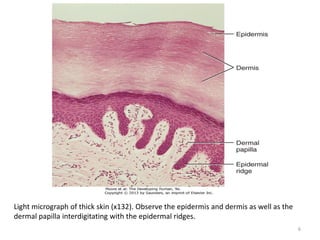

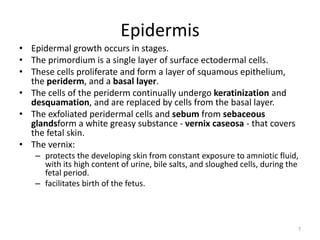

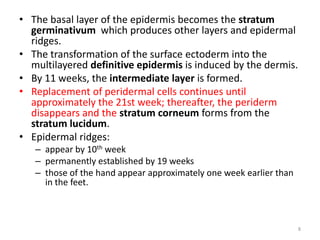

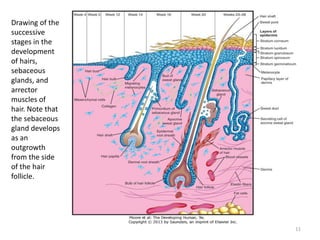

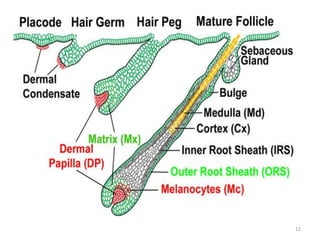

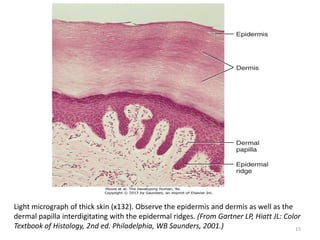

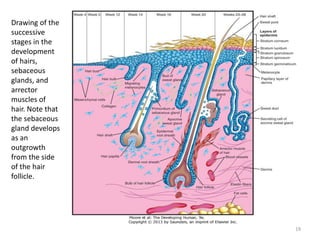

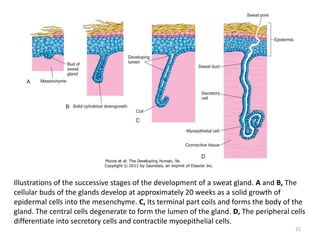

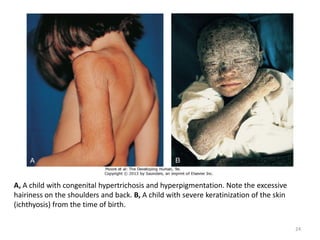

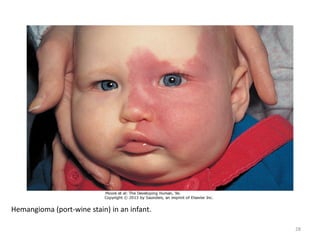

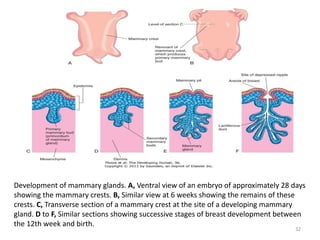

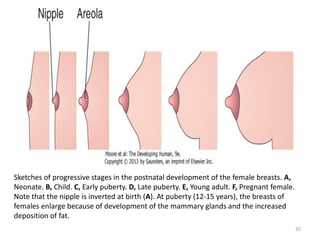

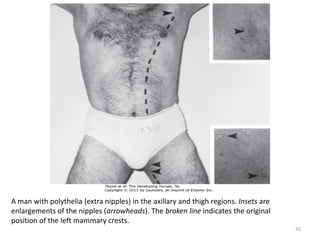

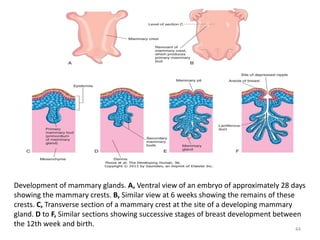

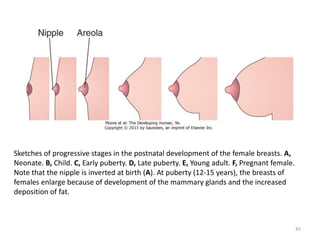

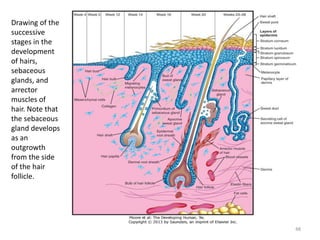

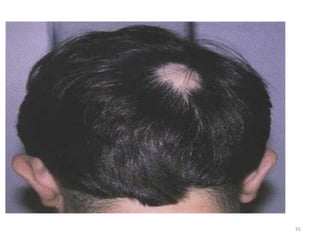

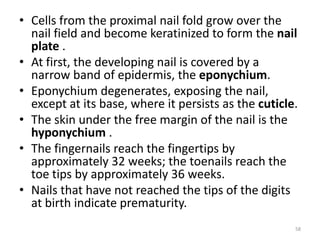

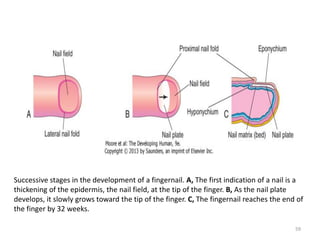

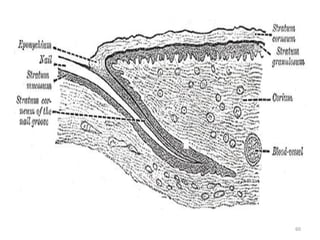

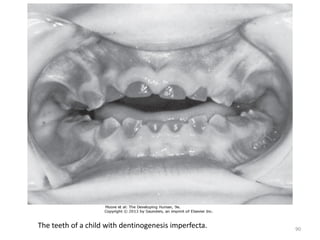

El documento detalla el desarrollo de la piel y sus estructuras asociadas, incluyendo las capas de la piel y la formación de glándulas como las sebáceas y sudoríparas durante la embriogénesis. Se explica la importancia de procesos como la queratinización, la formación de melanocitos, y las anomalías congénitas relacionadas, así como el desarrollo de las glándulas mamarias y variaciones como la ginecomastia y la presencia de senos supernumerarios. También aborda trastornos de la queratinización y la albinismo, brindando una visión integral de las condiciones de la piel y sus implicaciones clínicas.