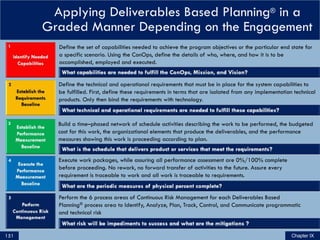

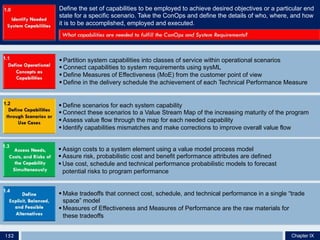

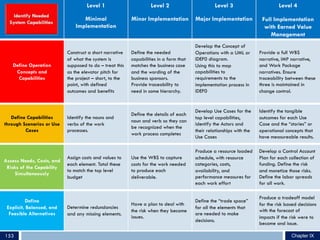

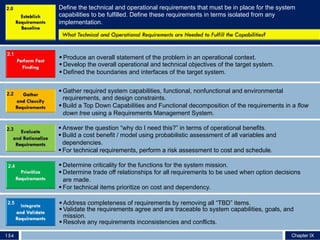

Deliverables Based Planning® integrates five critical program management principles with cost, schedule, and technical performance measures to increase the probability of program success. The document outlines these principles and practices through 10 chapters. It defines deliverables based planning, discusses its origins and benefits over conventional cost and schedule-only approaches. It describes identifying needed system capabilities, establishing requirements and performance baselines, executing work, and applying continuous risk management. The goal is to answer key questions around objectives, requirements, plans, execution and risks to deliver the needed capabilities on time and budget.

![The 10 Organizing Principles of

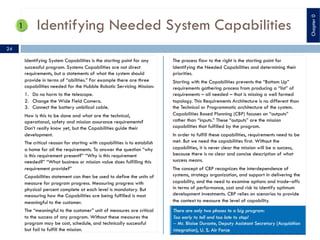

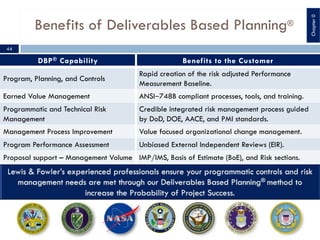

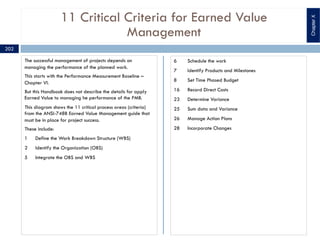

Deliverables Based Planning®

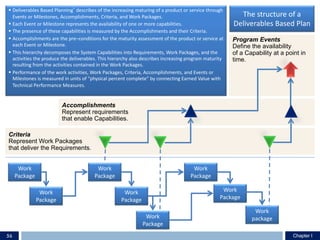

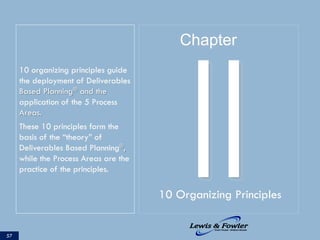

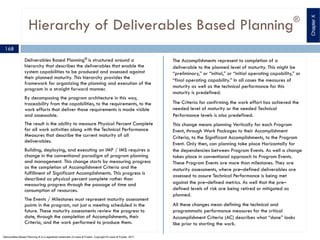

Principles are the source of guidance for the Deliverables

Based Planning®

Practices.

A principle is a “general truth, a law on which other are

founded or from which others are derived.” [Webster]

For the principles of program and project management to be

effective they must :

§ Express a basic concept

§ Be universally applicable

§ Be capable of straightforward expression

§ Be self evident

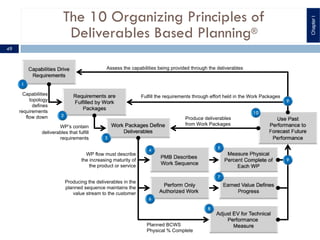

The 10 Principles of Deliverables Based Planning®

guide the

application of the four process areas. These principles

encompass the entire life cycle of a project or program, from

inception and the discovery of the business or system

capabilities, through requirements elicitation, to the creation

of the Performance Measurement Baseline (PMB), to the

execution of this baseline.

The principles of Deliverables Based Planning®

provide

several feedback loops to assure that subsequent activities

provide measurable information to correct gaps that exist in

the previous activities. This iterative and incremental

approach to program management assures the periods of

assessment for corrective actions are appropriately spaced

to minimize risk while maximizing the delivered value to the

program.

Deliverables Based Planning® can be the basis of

conventional as well as Lean program management methods.

The illustration the next page are the 10 Principles of

Deliverables Based Planning®. Each principle is developed in

detail later in this handbook. For now understanding the

dependencies between the principles is important.

Information produced by the practices derived from the

principles must be done in a sequential manner. This is not a

“waterfall” approach, but rather an incremental elicitation of

the information needed to successfully manage the program.

Skipping forward in the sequence of principle, creates

systemic risk for both the programmatic and technical

elements of the program.

48

ChapterI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-48-320.jpg)

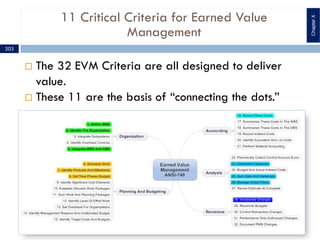

![Deliverables Based Planning® Processes

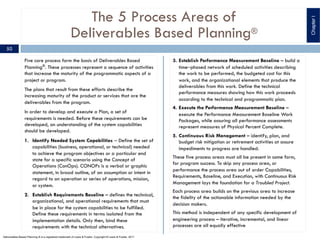

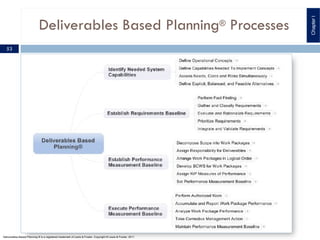

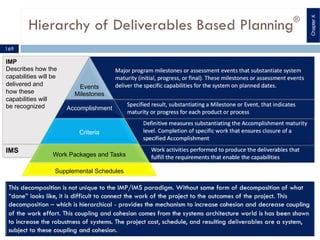

Deliverables Based Planning® is a comprehensive approach

to managing cost, schedule, and technical performance of

programs and projects by assessing the interaction between

programmatic and technical processes. The method starts by

capturing the technical and operational needs of the

proposed system. These are stated in a Concept of

Operations describing how the system operates, how it fulfills

the stated mission, what major components comprise the

system, and how they interact with each other.

From the capabilities description of the Concept of

Operation, technical and operational requirements are

elicited. These requirements define the development progress

of the deliverables captured in the Performance

Measurement Baseline (PMB). This PMB is constructed from a

collection of Work Packages, arranged in a logical network

describing the increasing maturity of the products or services

needed to deliver the stated capabilities. Measures of

physical percent complete are used for each Work Package

and the deliverables they produce. Deliverables Based

Planning® is a Systems Engineering approach to program

and project management [INCOSE], [Stevens].

This method incorporates all three aspects of a program

performance measurement process – Cost, Schedule, and

Technical Performance Measures (TPM).

The inclusion of the TPMs distinguishes the Lewis & Fowler

Deliverables Based Planning® from more conventional

approaches to Program, Planning, and Controls.

In conventional approaches, the cost and schedule baseline

and the variances generate the values for Earned Value.

In the Deliverables Based Planning®

method, measures of

Physical Percent Complete are derived from pre–defined

targets of Technical Performance. The Earned Value

variables are augmented with adjustments from the Technical

Performance compliance for each deliverable to produce a

true assessment of progress.

Technical Performance Measures integrate technical

achievement with earned value using risk assessments that

provides a robust program management tool to identify

early technical and programmatic disruptions to a program.

[Pisano] TPMs:

Provide an integrated view across all programmatic and

technical elements.

Support distributed empowerment implicit in the IPT

approach, through interface definitions.

Logically organizes data resulting from systems engineering,

risk management, and earned value processes.

Provide a "real time" indication of contract performance and

future cost and schedule risk.

Support the development of systems thinking within an

integrated program model focused on the interface

definitions.

ChapterI

52

Deliverables Based Planning ® is a registered trademark of Lewis & Fowler. Copyright ® Lewis & Fowler, 2011](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-52-320.jpg)

![Capabilities Drive System Requirements

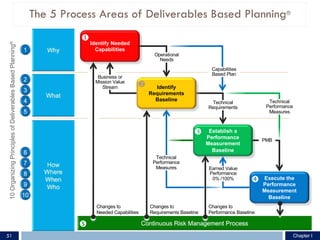

The principles for defining a capability address the

flexibility needed to ensure system responsiveness and

sustainability in a context of constant change, while

delivering tangible benefits to the buyer

These include: Agility, Tailorability, and measures of System

Element coupling and cohesion.

Governance principles provide guidance to institutionalize a

process, including its continued assessment and evolution over

time in support of the tangible system benefits.

These include: Enforced Rules & Responsibilities, Workflow

Guidance, Continuous Improvement, Transformation enablers.

The core concept in Capabilities Based development is the

focus on the delivery of value. The concept of “Value

Focused Thinking” starts with two methods of decision

making: the 1st

focuses on competitive analysis between the

various alternatives, and the 2nd focuses on attaining

organization values as the fundamental objective of any

decision making process. [Pagatto07]

During the development of the Concept of Operations for

each capability, assumptions must be made in the absence of

specific technical and operational information. To avoid

unwelcome surprises, some form of assumptions based

planning is needed. 1) Make operational plans, 2) Describe

plausible events, 3) Identify the “signposts” for potential

problems, 4) Discover shaping actions that shore up uncertain

assumptions, and 5) take hedging actions to better prepare

for the possibility that an assumption will fail [Dewer02]

Capabilities planning consists of several core processes to

describe the system capabilities in the absence of the

specific technical or operational requirements.

Discover what is not known by reaching a sufficient basic

knowledge level setting the problem space.

Identify problems by understanding the current process,

along with people and technology involved.

Establish boundaries and solution elements. These are

grouped into five categories:

1. Orientation principles align the process on a sound

theoretical basis issued from generally accepted practices

in the areas of engineering, modeling, and acquisition.

These principles include: Capability Thinking, Architecture

Models, Evolutionary Development, and Deliverables

Centric planning.

2. Communication principles enforce the standardization of

vocabulary and structure of information to be exchanged

within or outside the process.

These include: Standardized Formats and Common

Terminology to describes the system capabilities.

3. Collaboration principles enable active and timely

participation of all stakeholders involved in the

engineering of a capability.

These include: Collaborative Engineering and Information

Sharing between the contributors of the system capability

elements.

ChapterII

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-60-320.jpg)

![Requirements Identify Technical And

Process Deliverables

Inadequate requirements engineering is a common problem

in the development of any complex system.

There are many issues associated with requirements

engineering, including failure to define the system scope,

failure to foster understanding among the different

communities affected by the development of a given system,

and failure to deal with the volatile nature of requirements.

These problems lead to poor requirements and the

cancellation of development, or else the development of a

system that is later judged unsatisfactory or unacceptable,

has high maintenance costs, or undergoes frequent changes.

[Young04], [Grady06]

By improving requirements elicitation, the requirements

engineering process can be improved, resulting in enhanced

system requirements and potentially a much better system.

Requirements engineering is decomposed into the activities

of requirements elicitation, specification, and validation. Most

of the requirements techniques and tools today focus on

specification, i.e., the representation of the requirements.

The Deliverables Based Planning approach concentrates on

elicitation concerns, those problems with requirements

engineering that are not adequately addressed by

specification techniques.

The elicitation methodology to handle these concerns. Is

provided by [Cristel92].

Whatever the actual process used, the following activities

are fundamental to all Requirement Engineering

processes:[Sommerville05]

§ Elicitation – Identify sources of information about the

system and discover the requirements from these.

§ Analysis – Understand the requirements, their overlaps,

and their conflicts.

§ Validation – Go back to the system stakeholders and

check if the requirements are what they really need.

§ Negotiation – Inevitably, stakeholders’ views will differ,

and proposed requirements might conflict. Try to reconcile

conflicting views and generate a consistent set of

requirements.

§ Documentation – Write down the requirements in a way

that stakeholders and software developers can understand.

§ Management – Control the requirements changes that will

inevitably arise.

ChapterII

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-62-320.jpg)

![Requirements Identify Technical And

Process Deliverables

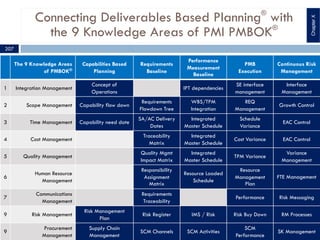

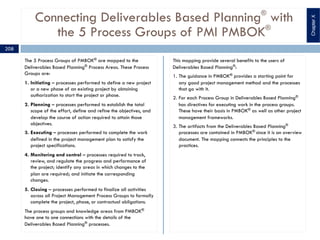

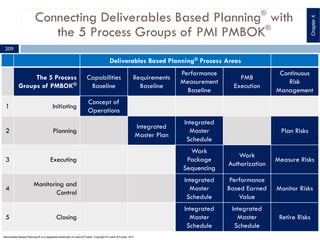

¨ Derive the system requirements for each system capability.

¨ Assure a requirement exists for each system capability needed to fulfill the

mission of the system.

¨ Develop the traceability from capabilities to requirements to produce a

“minimalist” system, with each requirement being present only because of a

needed system or mission capability.

¨ Test requirements by answering the question “why do we need this feature,

function, service, or capability?”

¨ Create Technical Performance Measures: [IEEE 1220]

¤ High priority requirements that have an impact on: mission accomplishment,

customer satisfaction, cost, system usefulness.

¤ High risk requirements or those where the desired performance is not currently

being met: the system uses new technology, new constraints have been added,

the performance goal has been increased, but the performance is expected to

improve with time.

¤ Requirements where performance can be controlled.

¤ Requirements where the program manager is able to rebalance cost, schedule

and performance.

ChapterII

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-63-320.jpg)

![Earned Value Describes Current

Performance

¨ Recognize Earned Value is cost based. Cost Variance and Schedule

Variance have the same units of measure – Dollars.

¨ Use the To Complete Performance Index (TCPI) and the Independent

Estimate At Completion (IEAC) as measures of progress derived from

Earned Value. But they are also measured in dollars.

¨ Using the TCPI and IEAC, the program manager has visibility into the

work performance needed to stay on schedule and the forecast cost

of this effort.

¨ Recognize the credibility of these indices depends on the credibility

of the underlying earned value numbers. This is the primary

motivation for maintaining good data on the program. Otherwise

the Earned Value numbers are not only wrong, they provide no real

value for guiding management in decisions that impact the future

performance of the program.

¨ Consider using Earned Schedule [ES] to complement Earned Value

[PMI EV]. Earned Schedule is a method of deriving schedule

performance from Earned Value data [Lipke], [Henderson04],

[Vanhoucke]

ChapterII

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-73-320.jpg)

![Performance Feedback Used To Adjust WP

Sequence and Resource Allocation

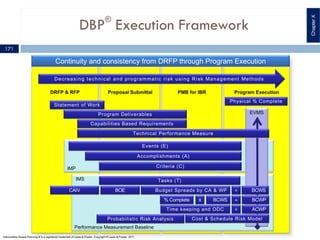

Earned Value Management (EVM) is a program management

tool integrates Cost and Schedule parameters as an early

warning system for future performance of the program.

But the EVMS standard states that EV is a measurement of

quantity (BCWP), not quality, of the work accomplished.

As far back as 1997, the discussion was integrating Cost,

Schedule, and Technical Performance. Robust systems

engineering and software engineering processes should

provide technical performance measures (TPM) and exit

criteria for assessing technical maturity that are

quantitatively linked to Earned Value.

Adjusting the To Complete Performance Index (TCPI) and the

Independent Estimate At Complete (IEAC) for less than

planned technical performance measurements – quality,

missing scope, delayed scope, or combinations of these and

other less than planned outcomes.

These TPMs are defined and evaluated to assess how well a

system is achieving its performance requirements. Technical

performance measurement uses actual or predicted values

from engineering measurements, tests, experiments or

prototypes.

The introduction the Earned Value Management Intent Guide

speaks to this but better guidance is needed [Solomon].

To provide the needed feedback for adjusting the TCPI and

IEAC values , the following activities need to be performed:

§ Include systems engineering activities in the schedule and

the Performance Measurement Baseline (PMB).

§ Establish thresholds or parameters for TPM in the program

plan.

§ Specify objective measures of progress as base measures

for EVM for: Development maturity to date, product’s

ability to satisfy requirements, Product metrics, including

TPM achievement‒to‒date.

§ Review program’s plans, activities, work products and

performance measurement baseline for consistency with

the requirements and the changes made to the

requirements baseline.

§ Incorporate risk mitigation plans in the program plan,

including changes to the PMB.

§ Include quantified risk assessments in the EAC depending

on the probability of risk occurrence and the impact on

cost objectives.

With this information, TCPI and IEAC can be adjusted to

reflect the Physical Percent Complete of the Work Packages,

not just the Cost and Schedule performance measures.

ChapterII

76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-76-320.jpg)

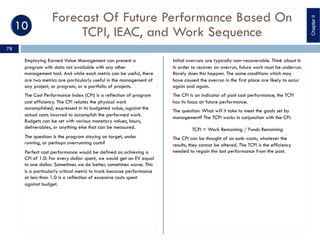

![Forecast Of Future Performance Based On

TCPI, IEAC, and Work Sequence

¨ Develop a new forecast of cost and schedule with the new

sequence of Work Packages.

¨ Base this forecast on the To Complete Performance Index (TCPI)

and the Independent Estimate At Complete (IEAC)

[Henderson08].

¨ There are five IEAC indices.

¤ IEAC1 = BAC / CPI

¤ IEAC2 = ACWP + (BAC – BCWP) / SPI

¤ IEAC3 = ACWP + (BAC – BCWP) / (SPI x CPI)

¤ IEAC4 = ACWP + (BAC – BCWP) / ((wt1 x SPI) + (wt2 x CPI))

¤ IEAC5 = ACWP + (BAC – BCWP) / CPIx

ChapterII

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-79-320.jpg)

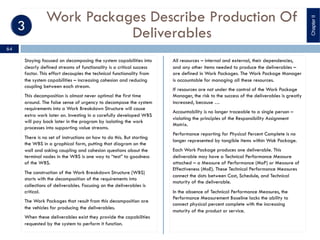

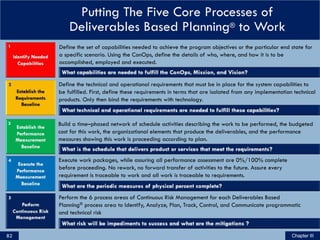

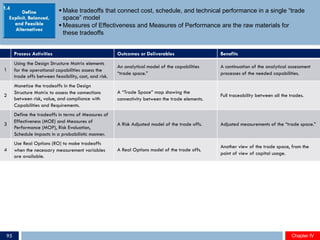

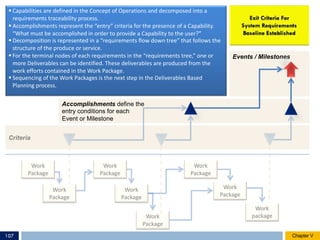

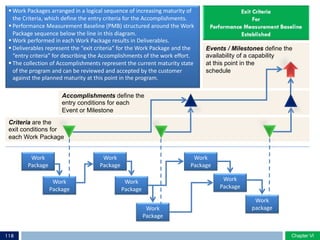

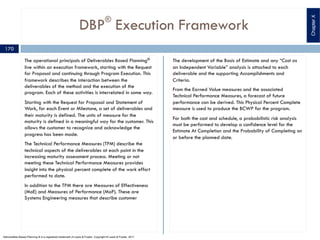

![Define the set of capabilities needed to achieve the program objectives or the particular end

state for a specific scenario. Using the ConOps, define the details of who, where, and how it

is to be accomplished, employed and executed.

Process Activities Outcomes or Deliverables Benefits

Using the supplied Statement of Work (SOW),

Statement of Objectives (SOO) extract a

description of the operational behavior of the

system in a Concept of Operations (ConOps)

and an associated process flow diagram.

A Process Flow Diagram of the system with

verbs in the boxes and nouns on the lines.

This can be done in Visio using the IDEFÆ

notation, or some other systems engineering

process and element diagramming method

[IDEFÆ].

A single diagram showing the system

components, the data or actions it produces,

and how these components interact.

This diagram shows the increasing maturity of

the system as is proceeds from left to right in

the Integrated Master Plan (IMP), through each

Program Event.

With the Process Flow Diagram, identify the

Accomplishments for each Milestone or Event.

Identify the dependencies between each

Accomplishment within and between the

Integrated Product Team (IPT) stream.

For each Event or Milestone, build a single

page chart for each Accomplishment for each

Integrated Product Team (IPT) members work

stream.

These diagrams show how each Event or

Milestone will be met from the completion of

the Accomplishment s.

With the dependencies identified, a top level

precedence diagram is now available for the

development of the Integrated Master

Schedule (IMS).

With each Accomplishment defined and

arranged in a sequence of increasing maturity

within the Event or Milestone, capture the

Criteria for the assessment of the

Accomplishment.

These Criteria are the “Exit Criteria” for the

Work Packages containing the Work Tasks.

The exit criteria for the work effort will be

defined in terms meaningful to the assessment

of Physical Percent Complete and the

completion of the Accomplishment.

Connections from Milestone or Event, to

Accomplishments and to the Criteria describe

the increasing maturity of the program.

This is more than just the traditional list of items

in the Integrated Master Plan. But a description

of the program’s process flow and its

increasing value.

1

Chapter III83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-83-320.jpg)

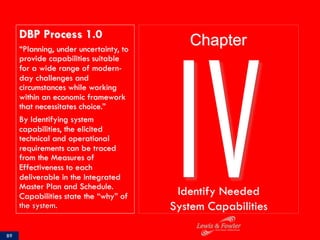

![1.0 – Identify Needed System Capabilities

Discovering needed system requirements begins with the a

narrative description of the needed Capabilities. Defining

capabilities provides a rational basis for making decisions

about requirements and allows planning to be responsive to

uncertainty. [TTCP]

This sounds like a tautology – a Chicken or the Egg problem.

But discovering the system requirements is difficult in the

absence of some higher level description of the needed

“Capabilities” of the desired system.

The concept of a “Capability” is a capacity or potential

[Davis]:

§ Provided by a set of resources and abilities

§ To achieve a measureable result

§ In performing a particular task

§ Under specific conditions

§ To specific performance standards

One approach to capturing the system capabilities is:

§ Start with the customers understanding the current and

future operational needs of their system.

§ Aligning those needs with industry standards and trends.

Translating the needs into system capabilities in the form of

system requirements specification or a Concept of

Operations. The Systems Requirements Specification is not

the same as a Technical Requirements Specification.

Establish a high–level system concept to identify system

components and their interfaces.

Guide the Integrated Product and Process Development

(IPPD) Teams, mentoring, and working with providers of

system components (both custom built and COTS) to ensure

they adhere to the overall system view.

Work with the customer to identify and mitigate technical

risks through a structured Risk Management process at the

Systems Requirements level.

Verify each system capability through a System Integration

and Qualification Test Plan.

Work with the customer to develop a Fielding and Product

Support Plan of the delivered system.

ChapterIV

90](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-90-320.jpg)

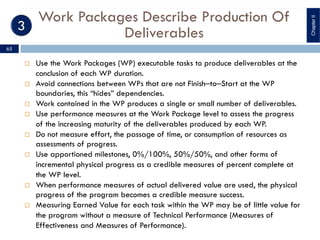

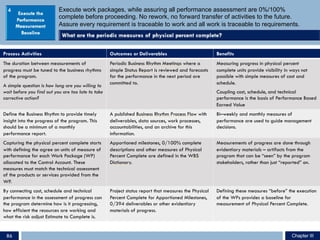

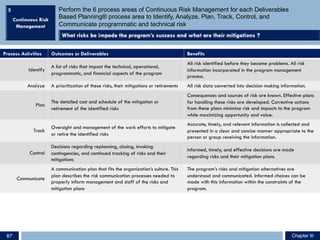

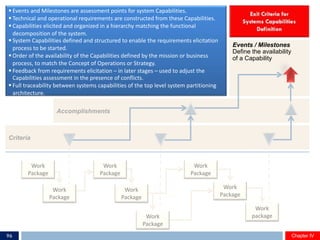

![§ Partition system capabilities into classes of service within operational scenarios

§ Connect capabilities to system requirements using sysML

§ Define Measures of Effectiveness (MOE) and Measures of Performance (MOP)

§ Define in the delivery schedule the achievement of each Technical Performance Measure

Process Activities Outcomes or Deliverables Benefits

1

Decompose the SOW, SOO,

and other RFP and system

documents, into a Concept of

Operations (ConOps).

§ A Top–to–bottom System Traceability Structure as the starting

point for the Requirements Management Baseline.

§ This structure is a “map” of the needed capabilities, their

interrelationships. This forms the basis of the requirements

flow down process.

Starting at the beginning of the program

capture capabilities in a form that can be

used to trace requirements, deliverables and

performance measures back to these

capabilities.

2

Build a map between the

System Capabilities in the

using the Design Structure

Matrix. [Browning99]

§ Design Structure Matrix showing dependencies between

operational capabilities.

§ Optimized structural alternatives suggesting re–architecting

of these dependencies.

Place all information in a common database

for analysis, publishing, and change control.

3

Define Measures of

Effectiveness (MOE) for each

capability.

How would the presence of

the capability be

recognized?

§ The Measures of Effectiveness (MOEs) are quantitative

measures that provide some insight into how effectively a

product or service is performing.

§ MoE’s are derived from stakeholder expectation statements.

§ MoE’s are deemed critical to the mission or operational

success of the system

§ For example: “95% of all work will be completed within 15

business days or the negotiated deadline.”

The basis of physical percent complete can

be defined with measures of effectiveness.

4

Define Measures of

Performance (MOP) for each

capability.

How would the presence of

the capability be

recognized?

§ MoPs serve as criteria to hierarchically organize these MoEs.

§ MoPs are qualitative or quantitative measures of system

capabilities or characteristics as seen from the providers

point of view.

§ MoPs are broad physical and performance parameters.

§ MoPs are components, or subsets, of MoEs; i.e., the "degree–

to–which" a system performs is one of a number of possible

measures of "how well" a system's task is accomplished.

The basis of physical percent complete can

be defined with measures of performance.

1.1

Chapter IVChapter IV92](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-92-320.jpg)

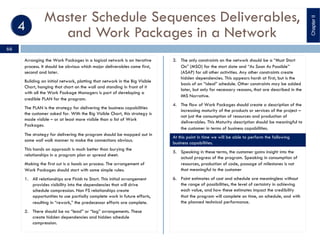

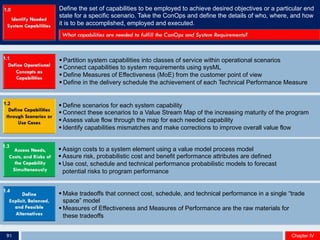

![§ Define scenarios for each system capability

§ Connect these scenarios to a Value Stream Map

§ Assess value flow through the map for each needed capability

§ Identify capabilities mismatches and make corrections to improve overall value flow

Process Activities Outcomes or Deliverables Benefits

1

List individual capabilities in scenario forms:

Use Case, process flows, or an operational

description

Scenario Based Descriptions using some

notation amenable to systems analysis –

IDEFÆ or SysML.

A single integrated representation of the

needed capabilities in a form assessable with

formal tools.

2

Assess dependencies between capabilities

using Design Structure Matrix (DSM) tool

Identify implicit dependencies as well as

explicit dependencies in a DSM.

Remove or minimize the implicit dependencies.

Address interface management issues with the

explicit dependencies.

3

Perform a Functional Area Analysis (FAA)

[INCOSE]

Characterize a specific area of the system in

terms of the operations that are required to

be performed to support the mission in a FAA.

Produces a focus on provides capabilities

based on functional scenarios rather than

specific technologies.

4

Performance a Functional Needs Assessment

(FNA) [INCOSE]

Assess the ability of the current and planned

systems to deliver the capabilities

identified in the FAA.

Produces a focus on identifying gaps in both

the scenarios and the functional behaviors

needed to fulfill those scenarios.

5

Perform a Functional Solutions Analysis (FSA)

[INCOSE]

An operationally–based assessment of all

potential organizational, training,

technological, material, leadership, personnel

and facilities and the supporting policy

approaches to solving (or mitigating) one or

more of the capability gaps identified in the

FNA.

Produces a focus of identifying all

participating elements of the system beyond

the technological deliverables.

1.2

Chapter IVChapter IV93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-93-320.jpg)

![§ Assign costs to a system element using a value model process model

§ Assure risk, probabilistic cost and benefit performance attributes are defined

§ Use cost, schedule and technical performance probabilistic models to forecast

potential risks to program performance

Process Activities Outcomes or Deliverables Benefits

1

For each implicit and explicit dependency

asses the nouns and verbs that cross the

interface boundary.

A weighted Trade Space Matrix for each

capability used to assess the cost and benefit

for each requirement that has alternative

choices of implementation.

ü Establish a common vocabulary for

making tradeoffs between desired or

needed capabilities in a form beyond just

personal assessment.

2

Assign cost, risk, and operational needs for

each capability and its impact on the

adjacent interface element.

A monetized assessment of each “trade

space” element used to build a credible

business model for the trade space decisions.

ü Document these trade offs in a formal

manner (sysML) that can be used by

analysis tools [Sharman].

3

Make assessments between cost, risk, and

operational needs in some form of

mathematical model.

Quantitative data showing the relationship

between these elements.

ü A tangible assessment of the “trade

space” between the programmatic

elements of the system.

4

From the data above, perform CAIV (Cost As

an Independent Variable) assessment. Set

aggressive, but realistic cost objectives when

defining operational requirements and

acquiring defense systems and managing

achievement.

Adjusted program cost objectives through the

use of cost‒performance analyses and

trade‒offs.

ü Execution of the program in a way to

meet or reduce stated cost objectives.

ü Realization that risks are present and

must be understood and managed in

order to achieve performance, schedule

and cost objectives.

5

For the CAIV process define the maximum

and minimum affordable price and the

maximum and minimum performance

thresholds.

Trade studies that address meeting user

performance needs and cost / resource

constraints, while performing on schedule with

minimal acceptable risk.

ü Visibility in the probability of success for

the program based on the trade space of

cost, schedule, and technical

performance.

1.3

Chapter IVChapter IV94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-94-320.jpg)

![Action Outcome

Implement Strategy

Ensure Capabilities

Prioritize Problems And Solutions

Identify Redundancies

Deliver Solutions

Chapter IVChapter IV97 † [Kossakowski]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-97-320.jpg)

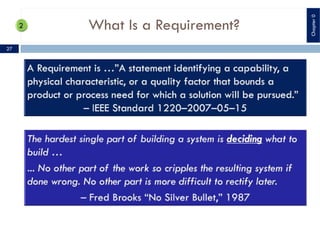

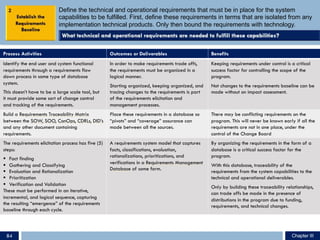

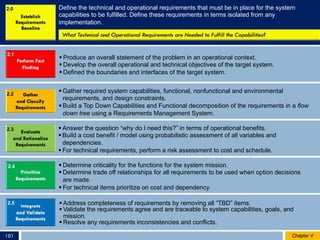

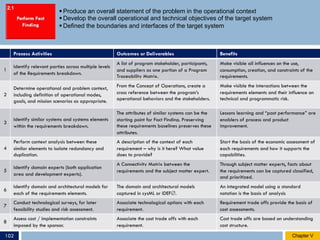

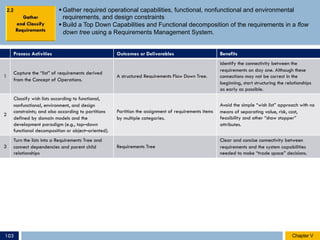

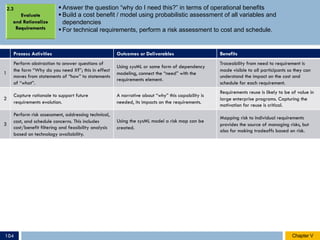

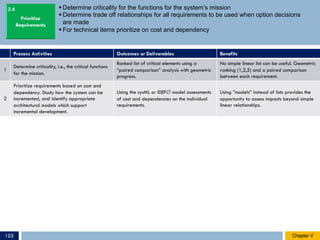

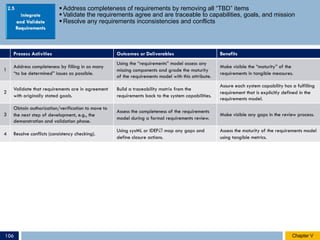

![2.0 – Establish the Requirements Baseline

Poorly formed requirements have been shown to contribute

as much as 25% to the failure modes of programs and

projects.

Requirements engineering can be decomposed into the

activities of requirements elicitation, specification, and

validation. Most of the requirements techniques and tools

today focus on specification, i.e., the representation of the

requirements. The Deliverables Based Planning® method

concentrates instead on elicitation. This method addresses

problems found with requirements engineering that are not

adequately addressed by specification techniques. [Christel]

This Deliverables Based Planning®

method incorporates

advantages of existing elicitation techniques while

addressing the activities performed during requirements

elicitation. These activities include fact–finding, requirements

gathering, evaluation and rationalization, prioritization, and

integration.

The requirements baseline is established starting with a Fact

Finding activity. This does not search for requirements, but

instead defines the boundaries of the requirements space.

With these boundaries established, the actual requirements

can be gathered and classified. The classification process is

an important state for assessing the need, evaluation, and

tradeoff processes.

Evaluating the requirements is done against the background

of the system boundaries and system capabilities.

With these evaluation, prioritization can start. These

prioritizations assess the order in which the requirements will

be deployed against the funding and resource limitations.

With the requirements prioritized, they can then be

integrated and validated. The integration process defines

the interdependencies between requirements that guide the

development of the Work Packages that produce the

deliverables that fulfill the requirements.

ChapterV

100](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-100-320.jpg)

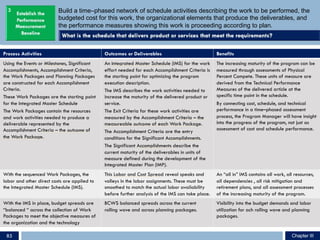

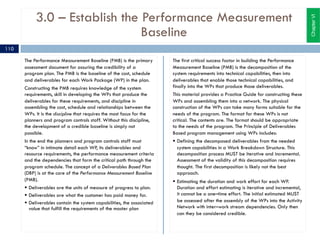

![§ Decompose the Project Scope into a product based Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

§ Decompose WBS into Work Packages describing the production of all deliverables

traceable to the requirements

Process Activities Outcomes or Deliverables Benefits

1

Map the desired system capabilities into

categories of system elements.

A Requirements Flow Down Tree from the

requirements to Work Packages that produce

deliverables.

Continue with full traceability from capability

to deliverables.

2

Build a Work Breakdown Structure derived

from the requirements categories. Focus on

products that are delivered from the work

effort.

Construct a product centric WBS. Not a

functional WBS. This WBS should follow the

100% rule [MIL 881] and the Mutually

Exclusive rule (no overlap between WBS

elements).

Assign resources and functional to each

deliverables in the WBS (product breakdown

tree). The WBS describes “planned outcomes”

not “planned activities.”

3

Decompose the requirements into collections

of deliverables at the terminal nodes of the

WBS.

Assembly collections of requirements into

logical “lumps of work” for assignment to

subject matter experts for estimating

Discovering how the “lumps of work” are

related is an iterative process. making them

visible is the start.

4

Produce a requirements traceability matrix in

some form of automated tool. Quality

Function Deployment (QFD) or Design

Structure Matrix (DSM). [Danilovic]

Using the WBS, the requirements tree and

other relationship models, use DSM to

construct a dependency model.

Making visible explicit and implicit

relationships is critical to verify requirements

and avoiding conflicts.

5

Examine the decomposition to determine if all

the components are clear and complete.

Using the model verify interdependencies are

needed.

Reduce coupling and increase cohesion of the

requirements.

6

Determine if each component listed is

absolutely necessary to fulfill the

requirements of the deliverable and verify

that the decomposition is sufficient enough to

describe the work.

Assessment of the necessity for each

requirement.

Complete the traceability from requirements

up to capabilities and from capabilities down

to requirements.

3.1

Chapter VIChapter VI112](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-112-320.jpg)

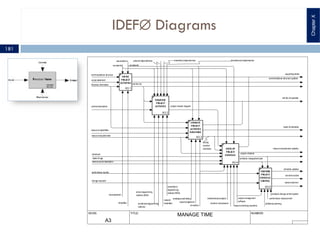

![IDEFÆ Diagrams

The IDEFÆ Functional Modeling method is designed to model

the decisions, actions, and activities of an organization or

system.[2] It was derived from the established graphic

modeling language Structured Analysis and Design

Technique (SADT) developed by Douglas T. Ross and SofTech,

Inc.. In its original form, IDEFÆ includes both a definition of a

graphical modeling language (syntax and semantics) and a

description of a comprehensive methodology for developing

models.[3] The US Air Force commissioned the SADT

developers "to develop a function model method for

analyzing and communicating the functional perspective of a

system. IDEFÆ should assist in organizing system analysis and

promote effective communication between the analyst and

the customer through simplified graphical devices".[2]

Where the Functional flow block diagram is used to show the

functional flow of a product, IDEFÆ is used to show data

flow, system control, and the functional flow of life cycle

processes. IDEFÆ is capable of graphically representing a

wide variety of business, manufacturing and other types of

enterprise operations to any level of detail. It provides

rigorous and precise description, and promotes consistency

of usage and interpretation. It is well-tested and proven

through many years of use by government and private

industry. It can be generated by a variety of computer

graphics tools. Numerous commercial products specifically

support development and analysis of IDEFÆ diagrams and

models.

An associated technique, Integration Definition for

Information Modeling (IDEF1x), is used to supplement IDEFÆ

for data intensive systems. The IDEFÆ standard, Federal

Information Processing Standards Publication 183 (FIPS 183),

and the IDEF1x standard (FIPS 184) are maintained by the

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

IDEFÆ may be used to model a wide variety of automated

and non-automated systems. For new systems, it may be used

first to define the requirements and specify the functions, and

then to design an implementation that meets the requirements

and performs the functions. For existing systems, IDEFÆ can

be used to analyze the functions the system performs and to

record the mechanisms (means) by which these are done. The

result of applying IDEFÆ to a system is a model that consists

of a hierarchical series of diagrams, text, and glossary cross-

referenced to each other. The two primary modeling

components are functions (represented on a diagram by

boxes) and the data and objects that inter-relate those

functions (represented by arrows).

180

ChapterX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-180-320.jpg)

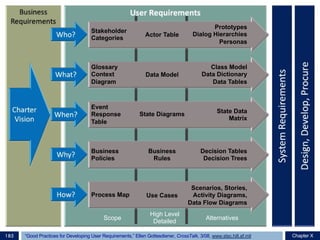

![Requirements Framework

Business requirements are statements of the business

rationale for the project. These requirements grow out of the

vision for the product which, in turn, is driven by mission (or

business) goals and objectives. The product’s vision statement

articulates a long-term view of what the product will

accomplish for its users. It should include a statement of scope

to clarify which capabilities are and are not to be provided

by the product. [Gottesdiener]

Putting all this information into a framework is next. We’ll do

this in preparation for our exercise that’s coming up.

User requirements define the software requirements from the

user’s point of view, describing the tasks users need to

accomplish with the product and the quality requirements of

the software from the user’s point of view. Users can be

broadly defined to include not only the people who access

the system but also inanimate users such as hardware

devices, databases, and other systems. In the systems

produced by most government organizations, user

requirements are articulated in their concept of operations

document.

This framework is one of many, but it’s simple, and even

useful for our current needs and the future needs as well. This

framework does several things:

1. It uses the separation of product and process that was

shown earlier.

2. It asks 5 of the 6 question in Rudyard Kipling “Six Honest

Serving Men” from “The Elephants Child.” “Where” is

missing, but we know where – we are at the location

where we are gathering requirements for our systems.

3. It demonstrates the layering of the requirements and

their evolutionary nature.

4. It shows some of the techniques for managing these

requirements.

Each requirements model represents information at a

different level of abstraction. A model such as a state

diagram represents information at a high level of

abstraction, whereas detailed textual requirements represent

a low level of abstraction. By stepping back from the trees

(textual requirements) to look at the forest (a state diagram),

the team can discover requirements defects not evident when

reviewing textual requirements alone.

Because the requirements models are related, developing

one model often leads to deriving another. Examples of one

model driving another model are the following:

§ Actors initiate use cases.

§ Scenarios exemplify instances of use cases.

§ A use case acts upon data depicted in the data model.

§ A use case is governed by business rules.

§ Events trigger use cases.

184

ChapterX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-184-320.jpg)

![Chapter I References

Principles and Practices of DBP®

[INCOSE] Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, INCOSE–TP–2003–002–03.1,

August 2007, www.incose.org

[Stevens] Systems Engineering: Coping with Complexity, Richard Stevens, Peter Brook, Ken Jackson, and Stuart Arnold, Prentice

Hall, 1998.

[Wood] Henri Fayol: Critical Evaluations in Business and Management, John C. Wood and Michael C. Wood, Routedge, 2002.

[Pisano] “Technical Performance Measurement, Earned Value, and Risk Management: An Integrated Diagnostic Tool for

Program Management,” Commander N. D. Pisano, SC, USN, Program Executive Office for Air ASW, Assault, and

Special Mission Programs (PEO(A))

AppendixA

213](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-213-320.jpg)

![Chapter II References

The 10 Principles of DBP®

[Pruitt03] Modeling Homeland Security: A Value Focused Thinking Approach, Kristopher Pruitt, Air Force Institute of Technology,

March 2003

[Solomon] Performance Based Earned Value, Paul Solomon.

[PMBOK] Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Project Management Institute.

[Brooks87] “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering, Fred Brooks, IEEE Computer, 10‒19, April 1987.

[Grady06] Systems Requirements Analysis, Jeffry O. Grady, Academic Press, 2006.

[Henderson08] “Further Development in Earned Schedule,” Kym Henderson, The Measureable News, Spring 2004.

[Lipke] “Schedule is Different,” Walter Lipke, The Measureable News, Summer 2003.

[Vanhoucke] “A Simulation and Evaluation of Earned Value Metrics to Forecast Project Duration,” M. S. Vanhoucke, Journal of

Operations Research Society, October 2007.

[IEEE1220] Standard for Application and Management of the Systems Engineering Process, Institute of Electrical and Electronics

Engineers, 09–Sep–2005

[Stevens98] Systems Engineering: Coping with Complexity, Richard Stevens, Peter Brook, Ken Jackson, and Stuart Arnold, Prentice

Hall, 1998.

[Young04] The Requirements Engineering Handbook, Ralph R. Young, Artech House, 2004

[Pisano] “Technical Performance Measurement, Earned Value, and Risk Management: An Integrated Diagnostic Tool for

Program Management,” Commander N. D. Pisano, SC, USN, Program Executive Office for Air ASW, Assault, and

Special Mission Programs (PEO(A))

[Christel92] “Issues with Requirements Elicitation,” Michael G. Christel and Kyo C. Kang, Technical Report, CMU/SEI–92–TR–12,

Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213.

[Danilovic] “Managing complex product development projects with design structure matrices and domain mapping matrices,”

Mike Danilovic and Tyson Browning, International Journal of Project Management, 25 (2007), pp. 300–314.

AppendixA

214](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-214-320.jpg)

![Chapter II References

The 10 Principles of DBP®

[Sharman] “Architectural optimization using real options theory and Dependency structure matrices,” David M. Sharman, Ali A.

Yassine+, Paul Carlile, Proceedings of DETC ’02 ASME 2002 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences

28th Design Automation Conference Montreal, Canada, September 29–October 2, 2002.

[Browning] “Modeling and Analyzing Cost, Schedule, and Performance in Complex System Product Development,” Tyson

Browning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, February 1999.

[TIPMH] The Integrated Project Management Handbook, Dayton Aerospace, 8 Feb 2002, Dayton Ohio.

[Davis] “Analytic Architecture for Capabilities–Based Planning, Mission–System Analysis, and Transformation,” Paul K. Davis,

RAND Corporation.

[INCOSE] Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, INCOSE–TP–2003–002–

03.1, August 2007, www.incose.org

AppendixA

215](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-215-320.jpg)

![Chapter III References

Deploying Deliverables Based Planning®

[IDEFÆ] http://www.idef.com/idef0.html

AppendixA

216

Deliverables Based Planning ® is a registered trademark of Lewis & Fowler. Copyright ® Lewis & Fowler, 2011](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-216-320.jpg)

![Chapter IV References

Identify Needed Systems Capabilities

[Davis] “Analytic Architecture for Capabilities–Based Planning, Mission–System Analysis, and Transformation,” Paul K. Davis,

RAND Corporation.

[Davis] Portfolio-Analysis Methods for Assessing Capability Options, Paul K. Davis, Russell D. Shaver, and Justin Beck, Rand

Corporation, 2008

[Sharman] “Architectural optimization using real options theory and Dependency structure matrices,” David M. Sharman, Ali A.

Yassine+, Paul Carlile, Proceedings of DETC ’02 ASME 2002 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences

28th

Design Automation Conference Montreal, Canada, September 29–October 2, 2002.

[Browning99] “Modeling and Analyzing Cost, Schedule, and Performance in Complex System Product Development,” Tyson

Browning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, February 1999.

[Maier] The Art of Systems Architecting, Mark W. Maier and Eberhardt Rechtin, CRC Press, 2000.

[Stevens] Systems Engineering: Coping With Complexity, Richard Stevens, Peter Brook, Ken Jackson, and Stuart Arnold, Prentice

Hall, 1998.

[Dewer] Assumption Based Planning: A Tool for Reducing Avoidable Surprises, James A. Dewar, Cambridge University Press,

2002.

[Kossakowski] Capabilities-Based Planning: A Methodology for Deciphering Commander’s Intent, Peter Kossakowski, Evidence Based

Research, Inc. 1595 Spring Hill Road, Suite 250 Vienna, VA 22182.

[Stalk] Competing on Capabilities: The New Rules for Corporate Strategy, George Stalk, Philip Evans, and Lawrence Shulman,

Harvard Business Review, No. 92209, March-April 1992.

[Jeffery] Effects-Driven, Capabilities-Based, Planning for Operations, Maj Kira Jeffery, USAF and Mr Robert Herslow.

[Saunders] Effects-based Operations: Building Analytical Tools, Desmon Saunder-Newton and Aaron B. Frank, Defense Horizons,

October 2002, pp 1-8.

[TTCP] Guide to Capability-Based Planning, Joint Systems and Analysis Group, MORS Workshop, October 2004,

Alexandria, VA. http://www.mors.org/

AppendixA

217](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-217-320.jpg)

![Chapter V References

Establish the Requirements Baseline

[Christel] “Issues with Requirements Elicitation,” Michael G. Christel and Kyo C. Kang, Technical Report, CMU/SEI–92–TR–12,

Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213.

[Young] The Requirements Engineering Handbook, Ralph R. Young, ArcTech House, 2004

[Boehm] Software Risk Management, Barry W. Boehm, IEEE Computer Society Press, 1989.

[David] Software Requirements Analysis & Specifications, Alan M. Davis, Prentice Hall, 1990.

[Sommerville] Requirements Engineering: A Good Practice Guide, Ian Sommerville and Pete Sawyer, John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

[Grady] Systems Requirements Practices, Jeffery O. Grady, McGraw Hill, 1993

[Ebert] Four Key Requirements Engineering Techniques, Christof Ebert, IEEE Software, May / June 2006.

[Leveson] Intent Specifications: An Approach to Building Human-Centered Specifications, Aeronautics and Astronautics, MIT.

[Leveson] Sample TCAS Intent Specification, Nancy Leveson and Jon Damon Reese, Software Engineering Corporation .

AppendixA

218](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-218-320.jpg)

![Chapter VI References

Establish the Performance Measurement Baseline

[Danilovic] “Managing complex product development projects with design structure matrices and domain mapping matrices,”

Mike Danilovic and Tyson Browning, International Journal of Project Management, 25 (2007), pp. 300–314.

[MIL 881] MIL–STD–881A, Work Breakdown Structures.

[Morris] The Management of Projects, Peter W. G. Morris, Thomas Telford, 1994

[Williams] Modelling Complex Projects, Terry Williams, John Wiley & Sons. 2002.

[Brown] The Handbook of Program Management, James T. Brown, McGraw Hill, 2007.

[Brown] AntiPatterns in Project Management, William J. Brown, Hays W. McCormick III, and Scott W. Thomas, John Wiley &

Sons, 2000

AppendixA

219](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-219-320.jpg)

![Chapter VII Reference

Execute the Performance Measurement Baseline

[Fleming] Earned Value Management, 3rd

Edition, Quentin W. Fleming and Joel M. Koppelman, Project Management Institute, 2005.

AppendixA

220](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-220-320.jpg)

![Chapter VIII References

Continuous Risk Management

[Bolles] “Understanding Risk Management in the DoD,” Mike Bolles, Acquisition Research Journal, Volume 10, pp. 141–145,

2003.

[Conrow] Effective Risk Management: Some Keys to Success, 2nd

Edition, Edmund H. Conrow, AIAA Press, 2003.

[Hall] Managing Risk: methods for Software Systems Development, Elaine M. Hall, Addison Wesley, 1998

[NDIA] Integrating Risk Management with Earned Value Management, National Defense Industry Association.

[Risk] Three point estimates and quantitative risk analysis a process guide for risk practitioners, Acquisitioning Operating

Framework, UK Ministry of Defense, http://www.aof.mod.uk/index.htm

[Hillson] Effective Opportunity Management for Project: Exploring Positive Risk, David Hillson, Taylor & Francis, 2004.

[Bennatan] Catastrophe Disentanglement: Getting Software Projects Back on Track, E. M. Bennatan, Addison Wesley, 2006.

[Karolak] Software Engineering Risk Management, Dale Walter Karolak, IEEE Computer Society Press, 1998.

[Jones] Assessment and Control of Software Risks, Capers Jones, Prentice Hall, 1994

[AOF] Three Point Estimates and Quantitative Risk Analysis - A Process Guide For Risk Practitioners - version 1.2 May 2007 -

Risk Management – AOF, http://www.aof.mod.uk/aofcontent/tactical/risk/downloads/3pepracgude.pdf

[Lister] How much risk is too much risk?, Tim Lister, Boston SPIN, January 20th

, 2004.

[INCOSE] Risk Management Maturity Level Development, INCOSE Risk Management Working Group, April 2002.

[Arízaga] “A Methodology for Project Risk Analysis using Bayesian Belief Networks within a Monte Carlo Simulation Environment,”

Javier F. Ordóñez Arízaga, University of Maryland, College Park, 2007.

[USAF] AFMC PAMPHLET 63-101, 9 July 1997.

[Valerdi] An Approach to Technology Risk Management, Ricardo Valerdi and Ron J. Kohl, Engineering Systems Division

Symposium, MIT, Cambridge, MA 29-31 March 2004.

AppendixA

221](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-221-320.jpg)

![Chapter VIII References

Continuous Risk Management

[Bahill] “An Industry Standard Risk Analysis Technique,” A Terry Bahill and Eric D. Smith, Engineering Management Journal,

Vol. 21 No 4., December 2009.

[ASE] Risk Management Process and Implementation, American Systems Corporation, 2003.

[Kandaswamy] The Basics of Monte Carlo Simulation: A Tutorial, S. Kandaswamy, Proceedings of the Project Management Institute

Seminars & Symposium, 1-10 November 2001.

[NASA] Bayesian Inference for NASA Probabilistic Risk and Reliability Analysis, NASA/SP-2009-569, June 2009.

[Alberts] Common Elements of Risk, Christopher J. Alberts, CMU/SEI-2006-TN-014, April 2006.

[Conrow] “Development of Risk Management Defense Extensions to the PMI Project Management Body of Knowledge,”

Edmund H. Conrow, Acquisition Review Quarterly, Spring 2003.

[Dorofee] Continuous Risk Management Guidebook, Audrey J. Dorofee, Julie A. Walker, Christopher J. Alberts, Ronald P.

Higuera, Richard L. Murphy, and Ray C. Williams, Software Engineering Institute, 1996.

[DoD] Risk Management Guide for DoD Acquisition, Fifth Edition, June 2002.

[Drucker] Emerging Practice: Joint Cost & Schedule Risk Analysis, Eric Drucker, 2009 St. Louis SCEA Chapter Fall Symposium,

St’ Louis, MO.

[Coleman] Making Risk Management Tools More Credible: Calibrating the Risk Cube, Richard L. Coleman, Jessica R.

Summerville, and Megan E. Dameron, SCEA 2006, Washington, D.C., 12 June 2006.

[Book] A Theory of Modeling Correlations for Use in Cost-Risk Analysis, Stephen A. Book, Third Annual Project

Management Conference, NASA, Galveston, TX, 21-22 March 2006.

[Butts] The Joint Confidence Level Paradox: A History of Denial, 2009 NASA Cost Symposium, 28 April 2009.

AppendixA

222](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-222-320.jpg)

![Chapter X References

Tools and Artifacts

[Yassine] An Introduction to Modeling and Analyzing Complex Product Development Processes Using the Design Structure

Matrix (DSM) Method, Ali A. Yassine

[Browning] Browning, T. & Eppinger, S., “Modeling Impacts of Process Architecture on Cost and Schedule Risk in Product

Development,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering. Management, 49(4): 428–442, 2002.

[Danilovic] Managing complex product development projects with design structure matrices and domain mapping matrices,

Mike Danilovic and Tyson R. Browning, International Journal of Project Management.

[DoD] Risk Management Guide for DOD Acquisition, US Department of Defense.

[FIPS 184] Federal Information Processing Standard Publication 184: Integrated Definition for Information Modeling, 21

December 1993.

[Gottesdiener] Good Practices for Developing User Requirements, Crosstalk, May 2008, pp. 13-17.

AppendixA

223](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deliverablesbasedplanninghandbookv8-201224023045/85/Deliverables-based-planning-handbook-223-320.jpg)