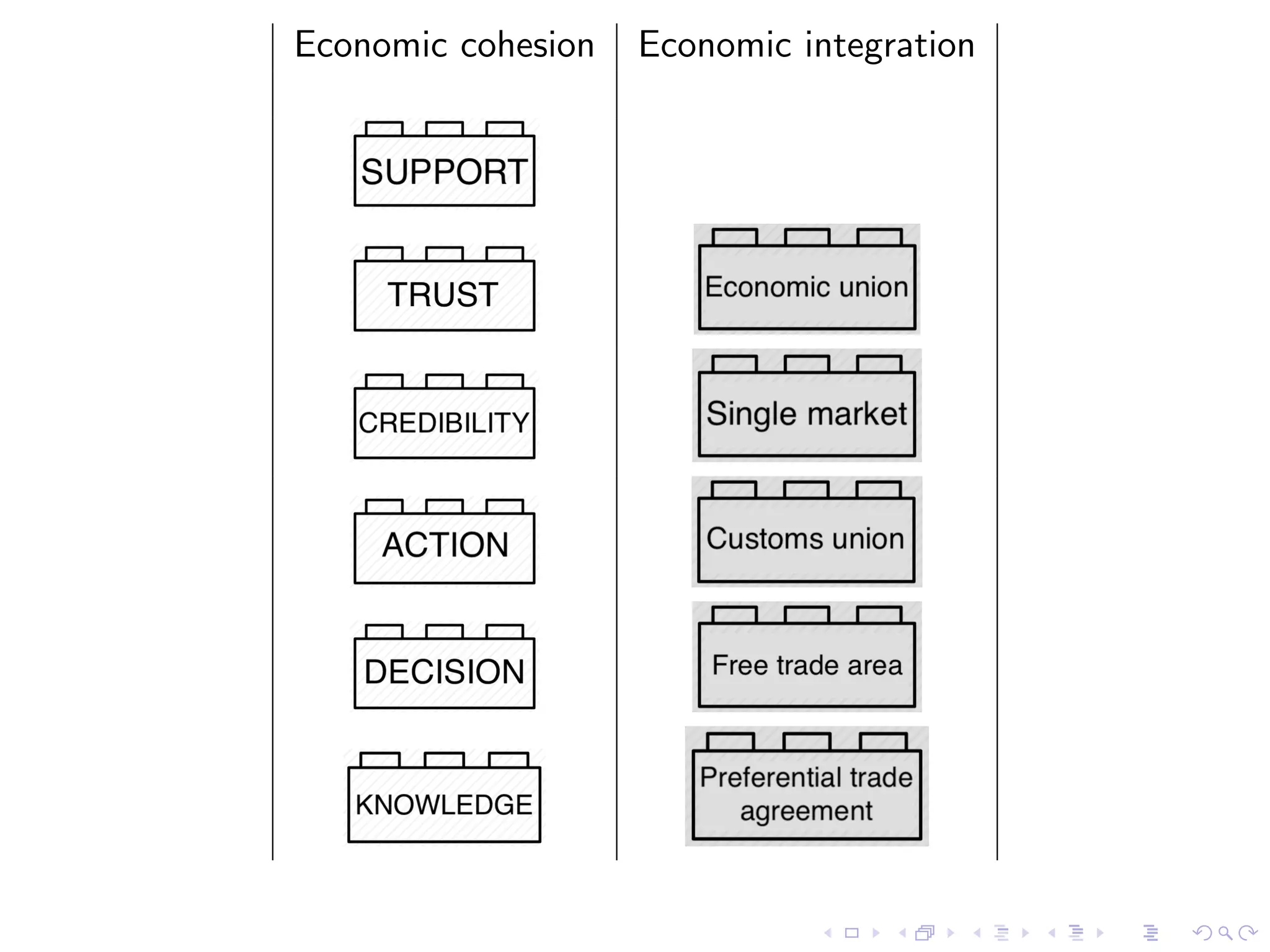

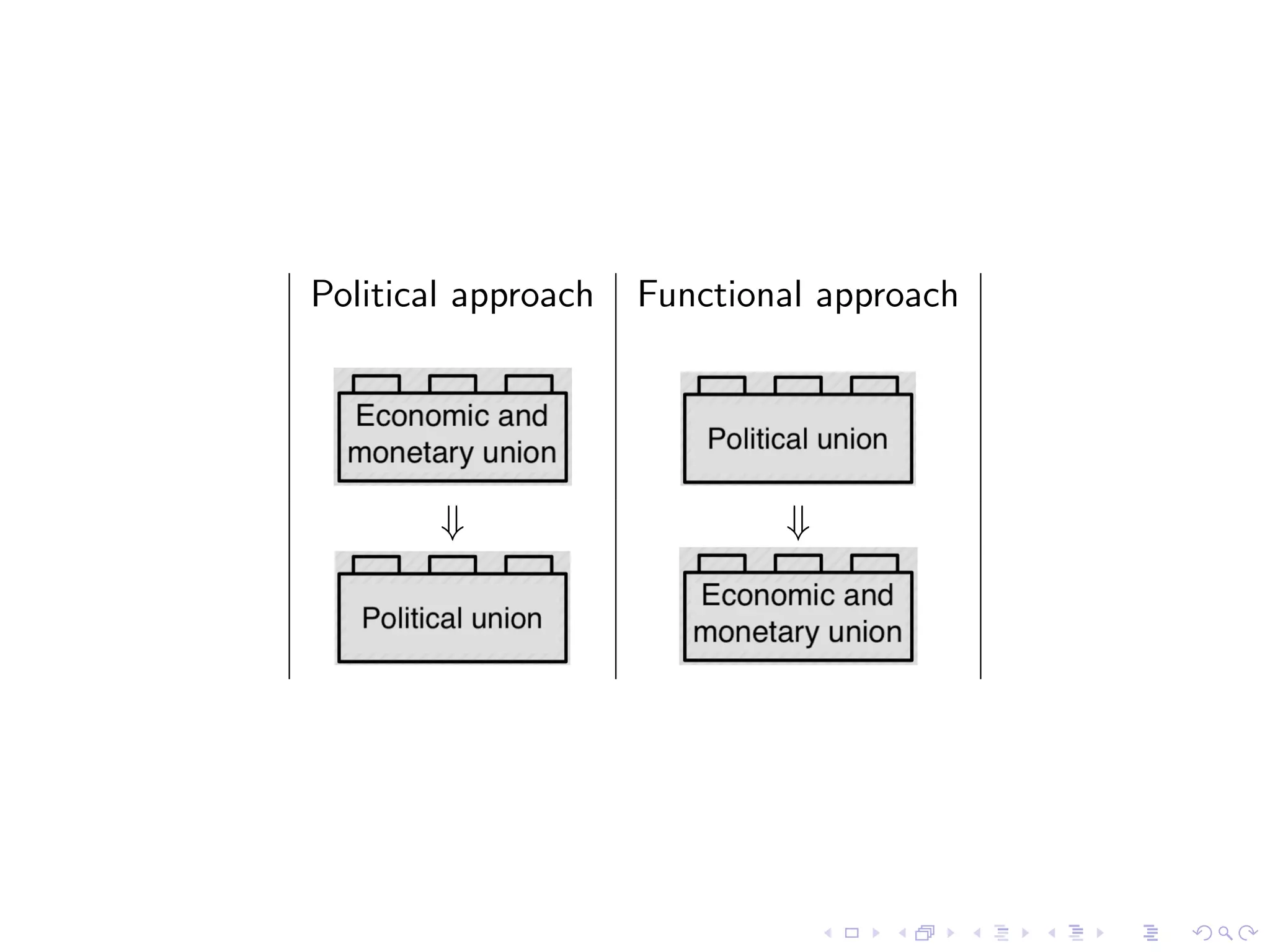

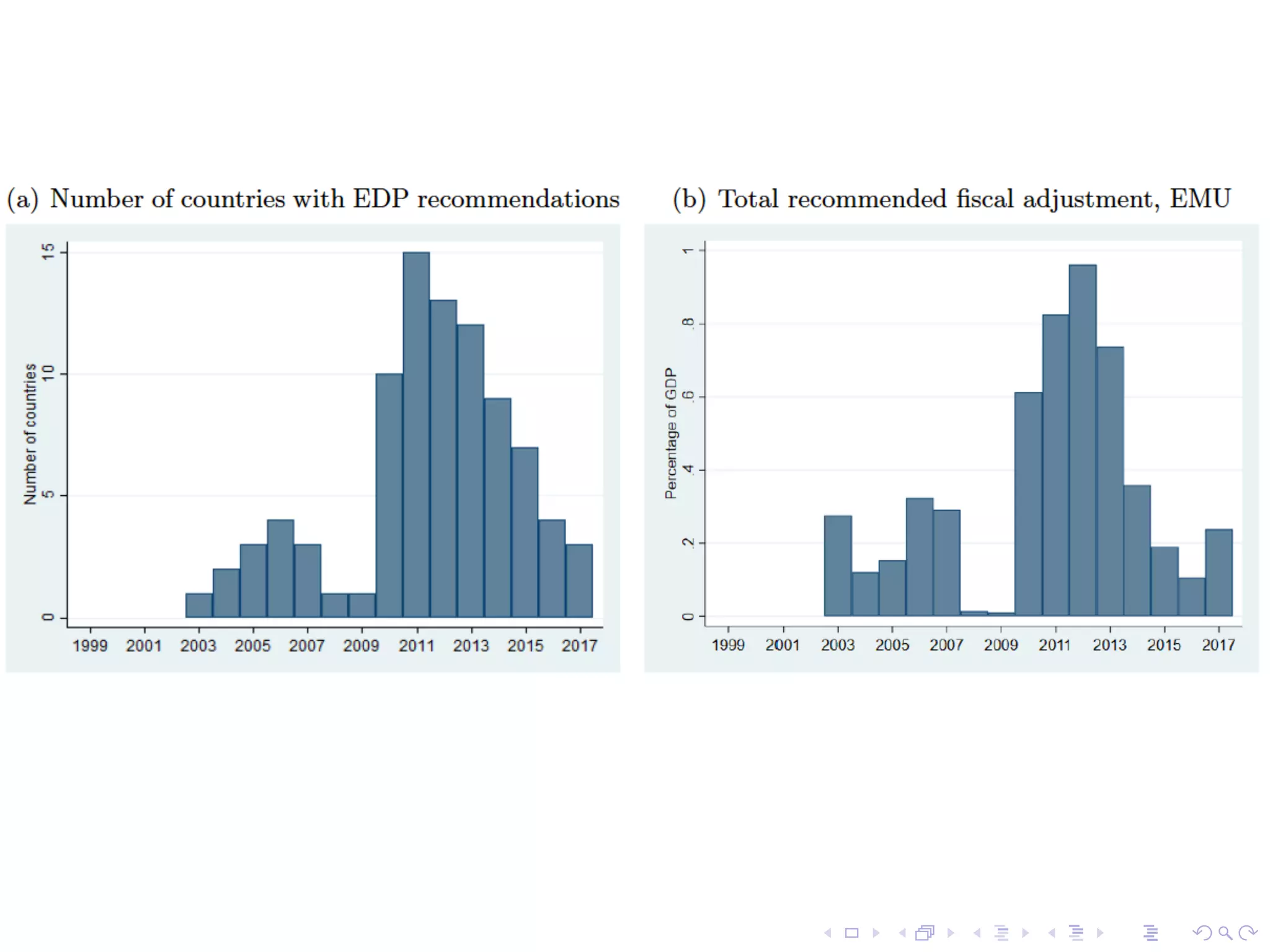

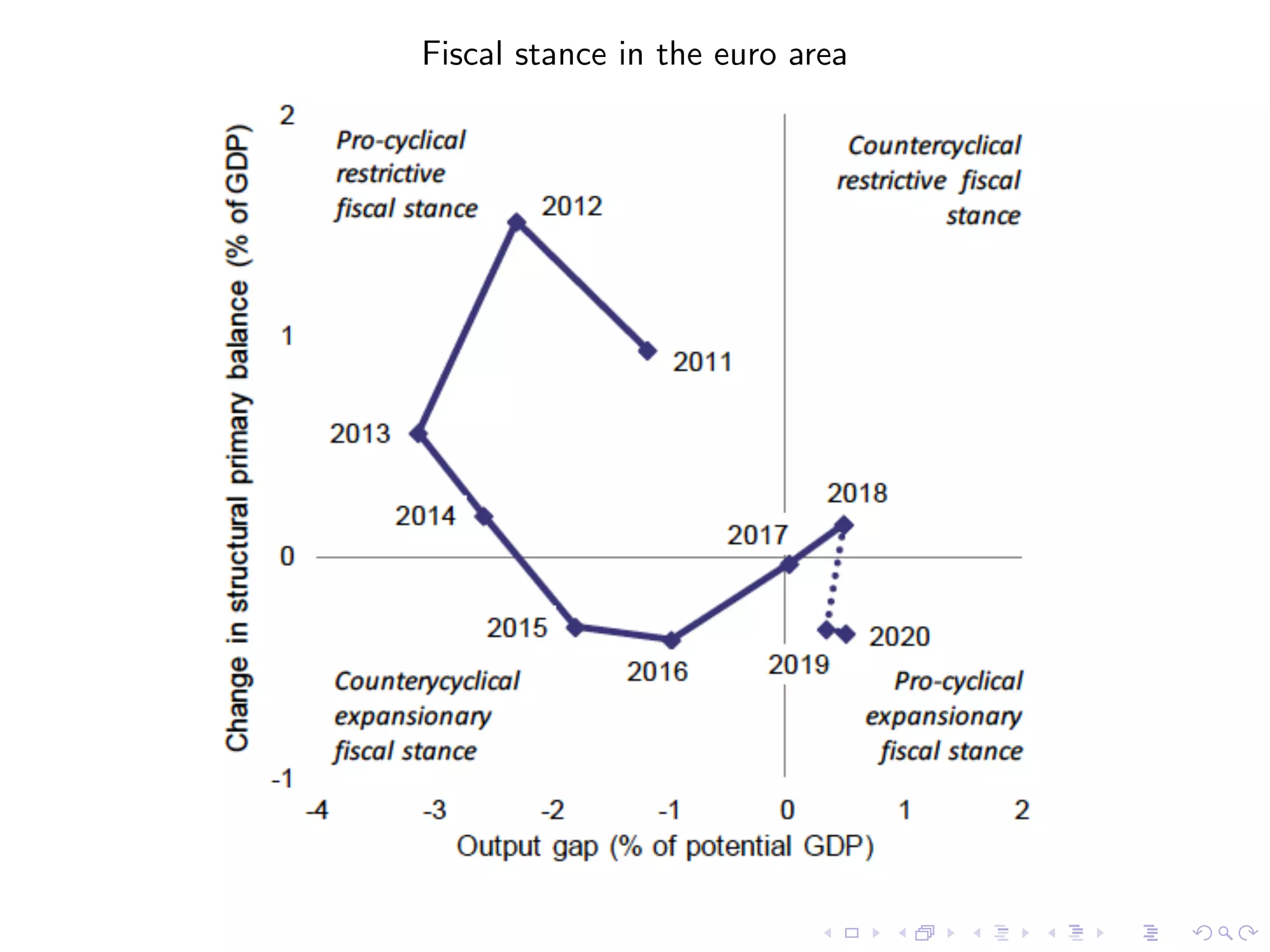

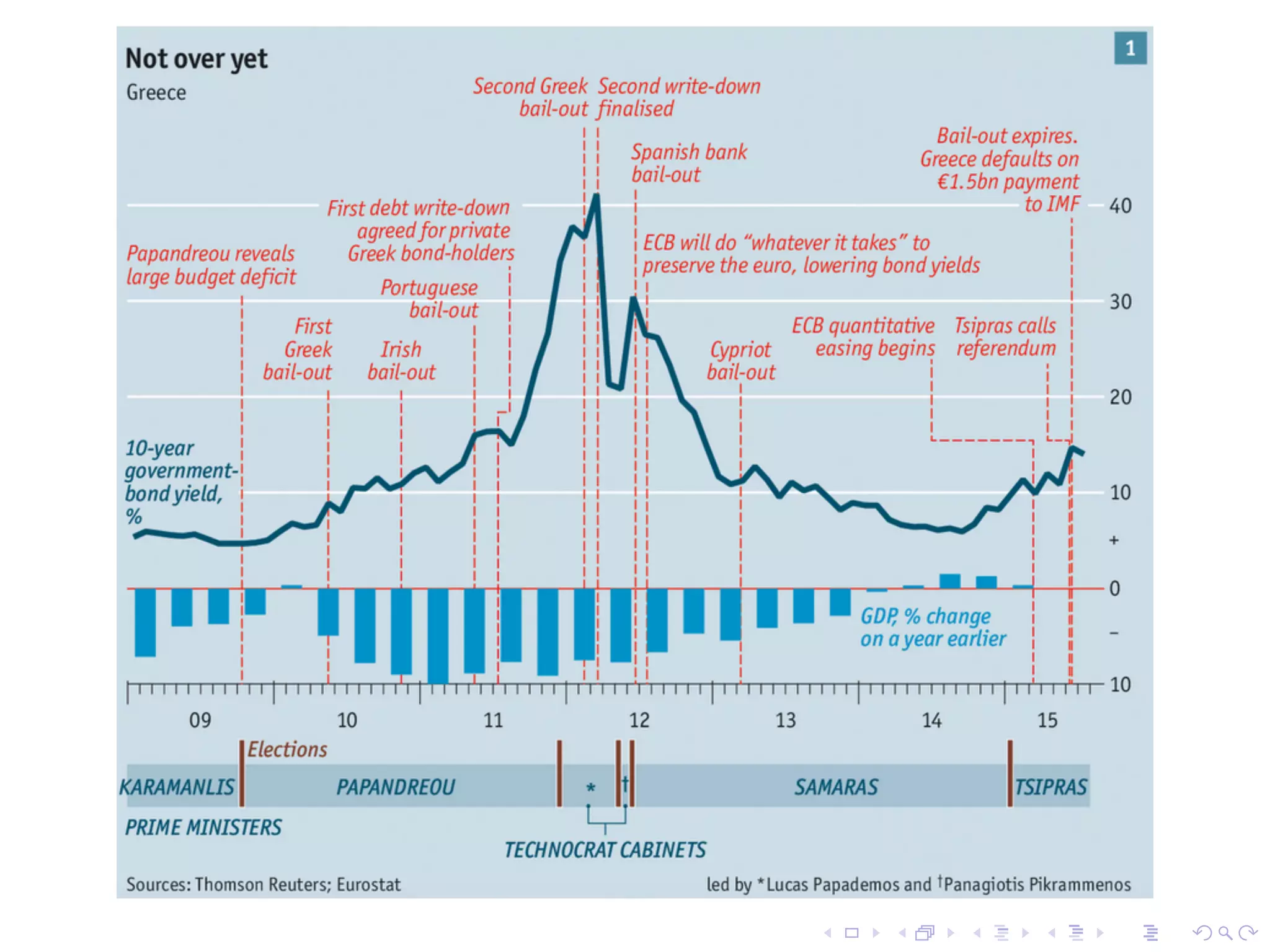

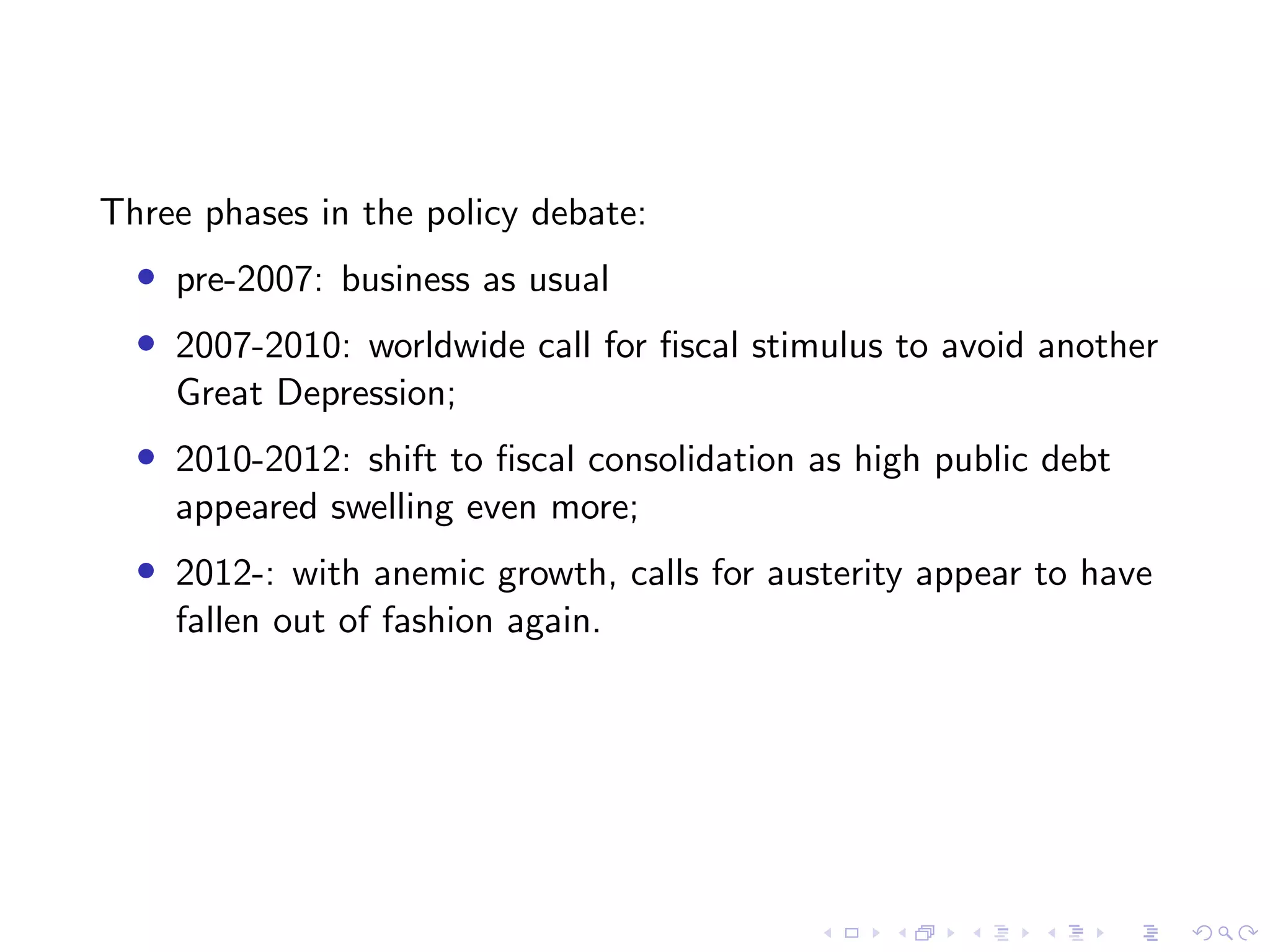

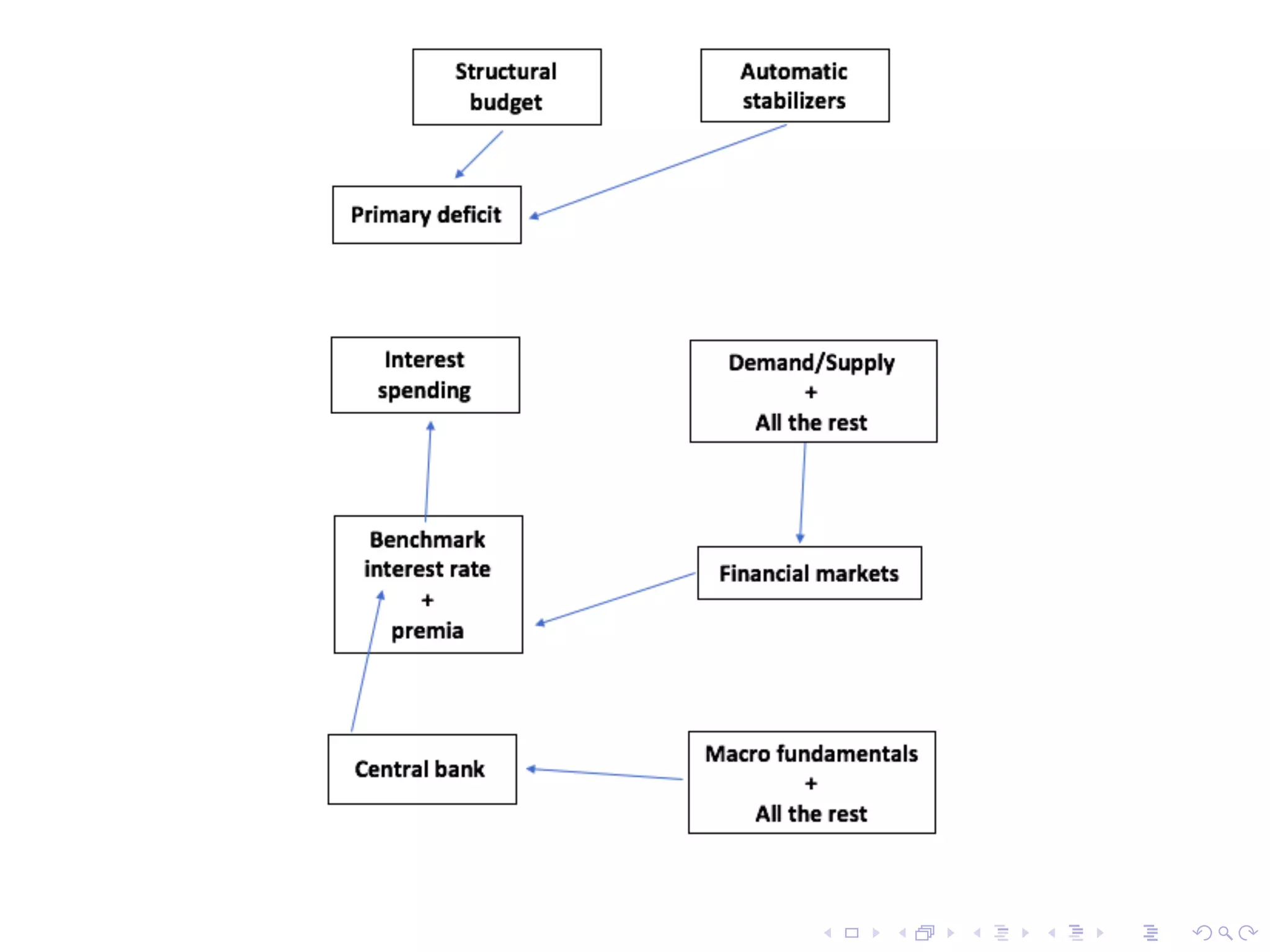

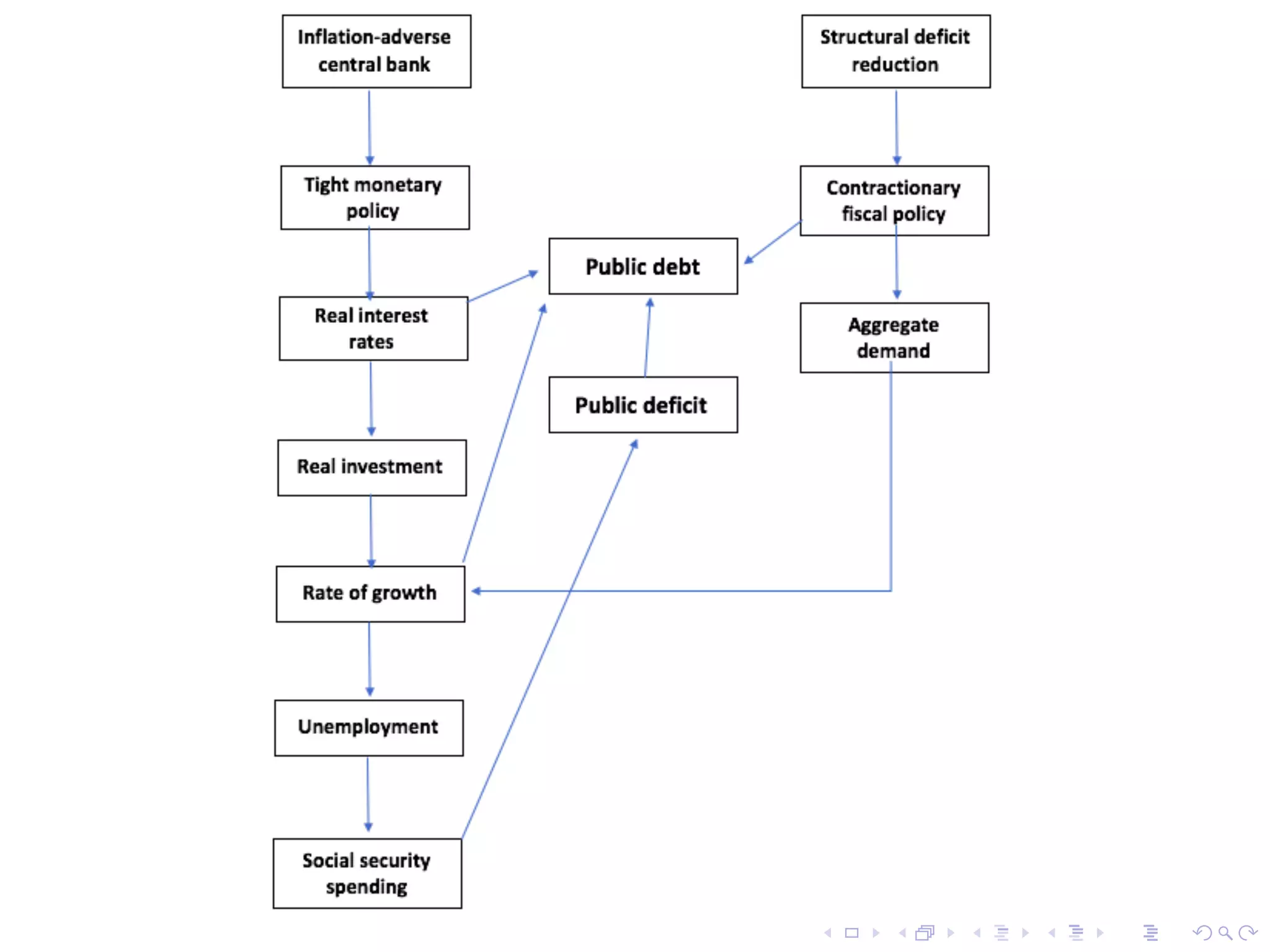

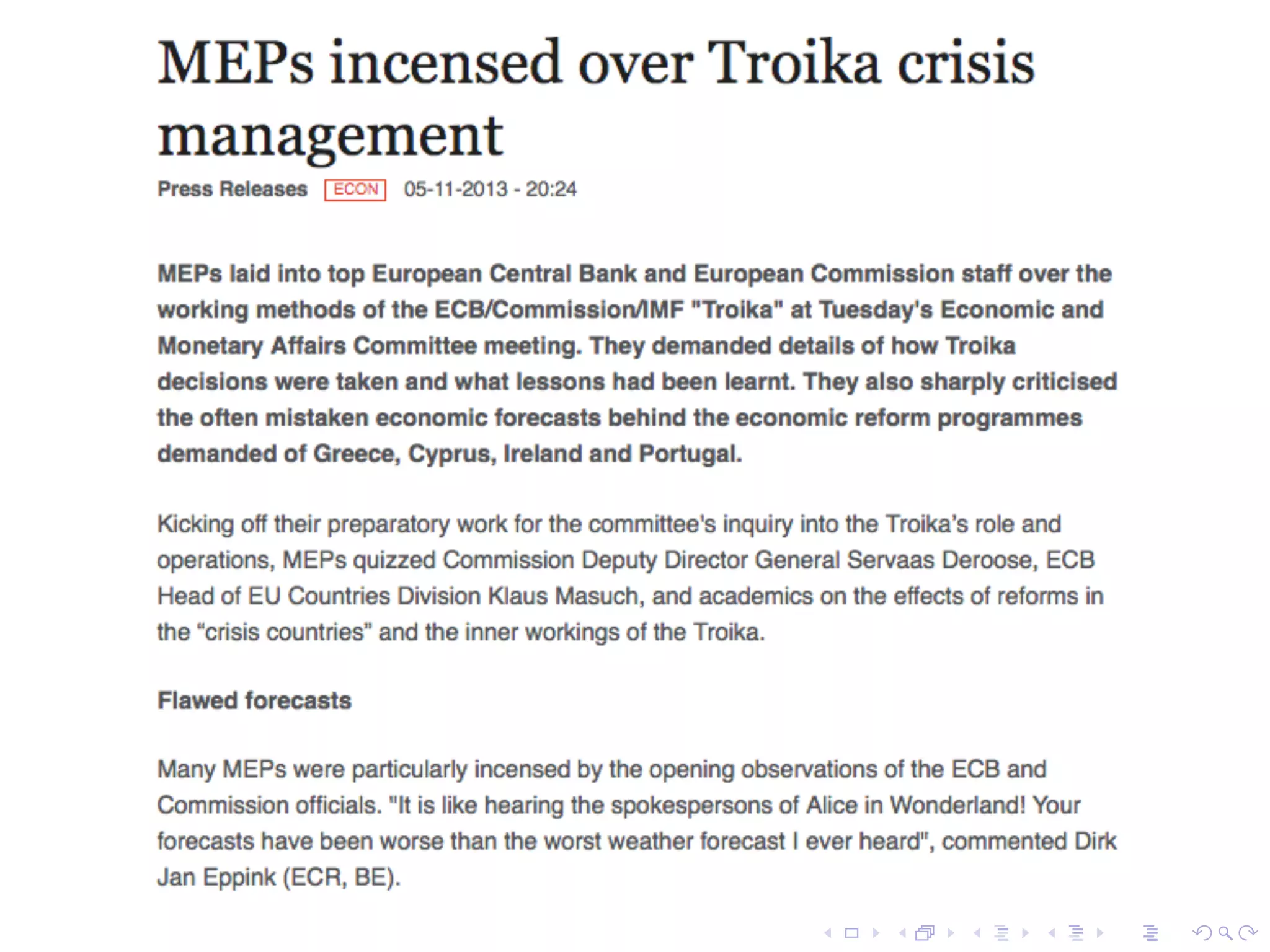

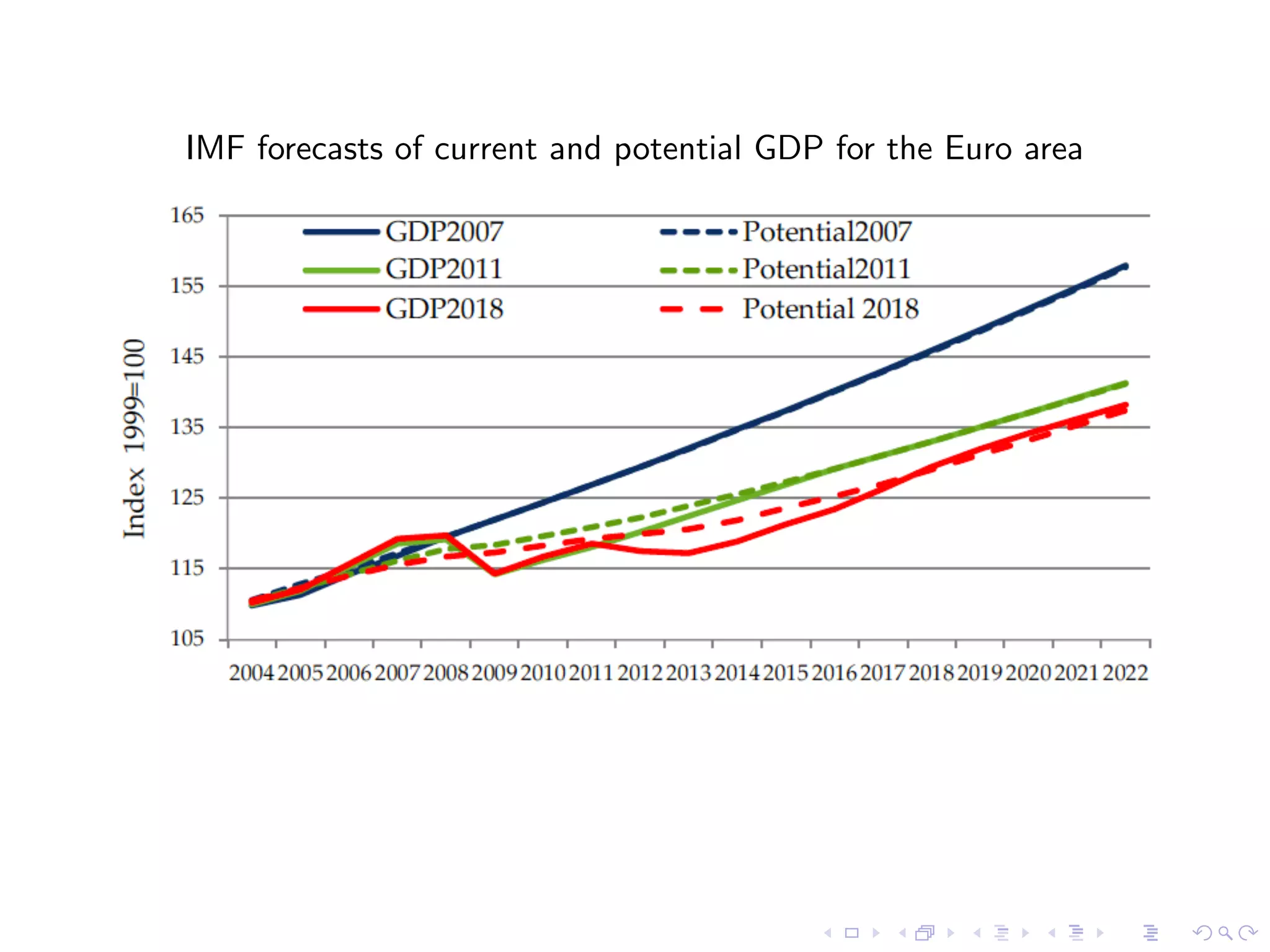

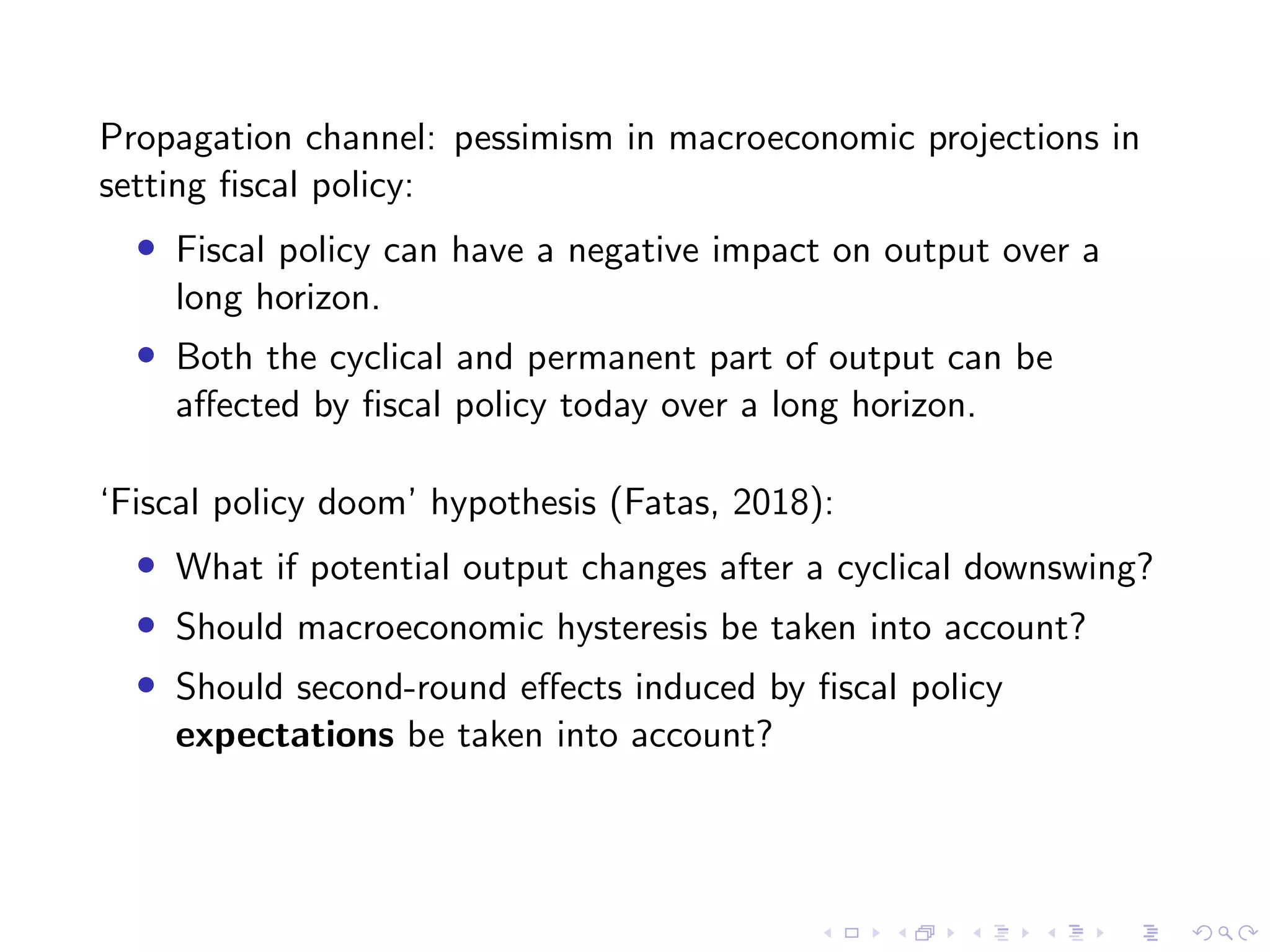

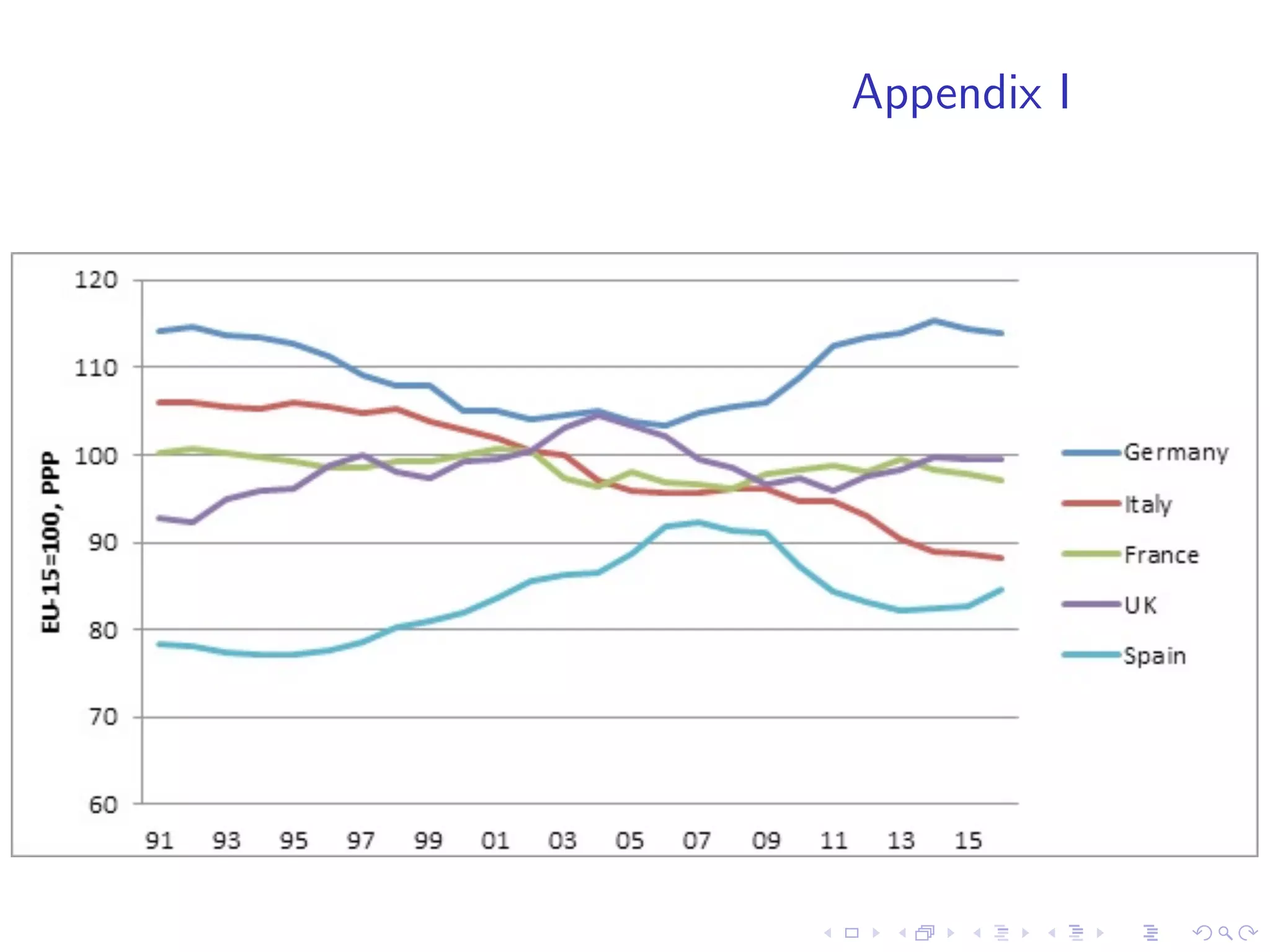

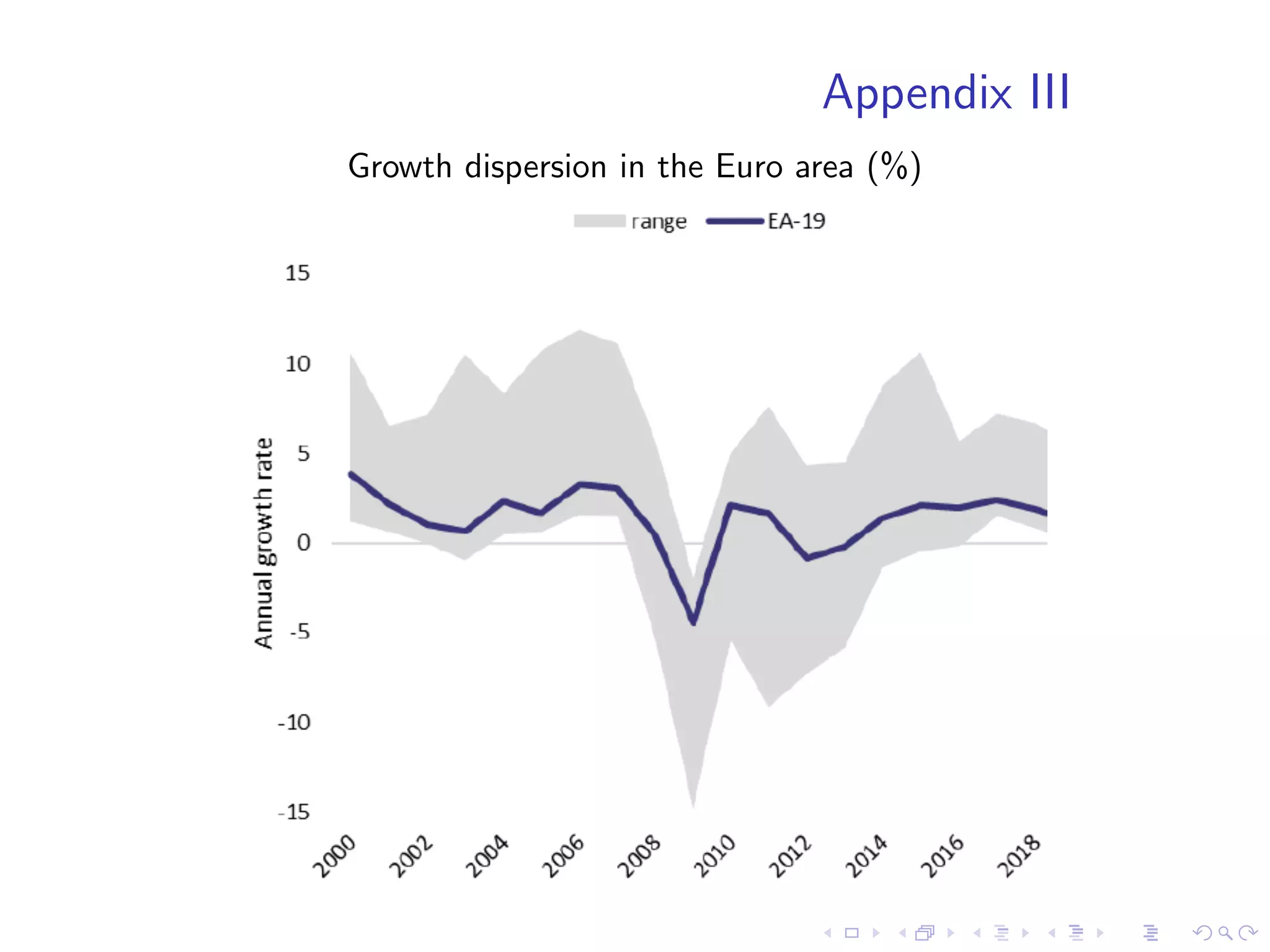

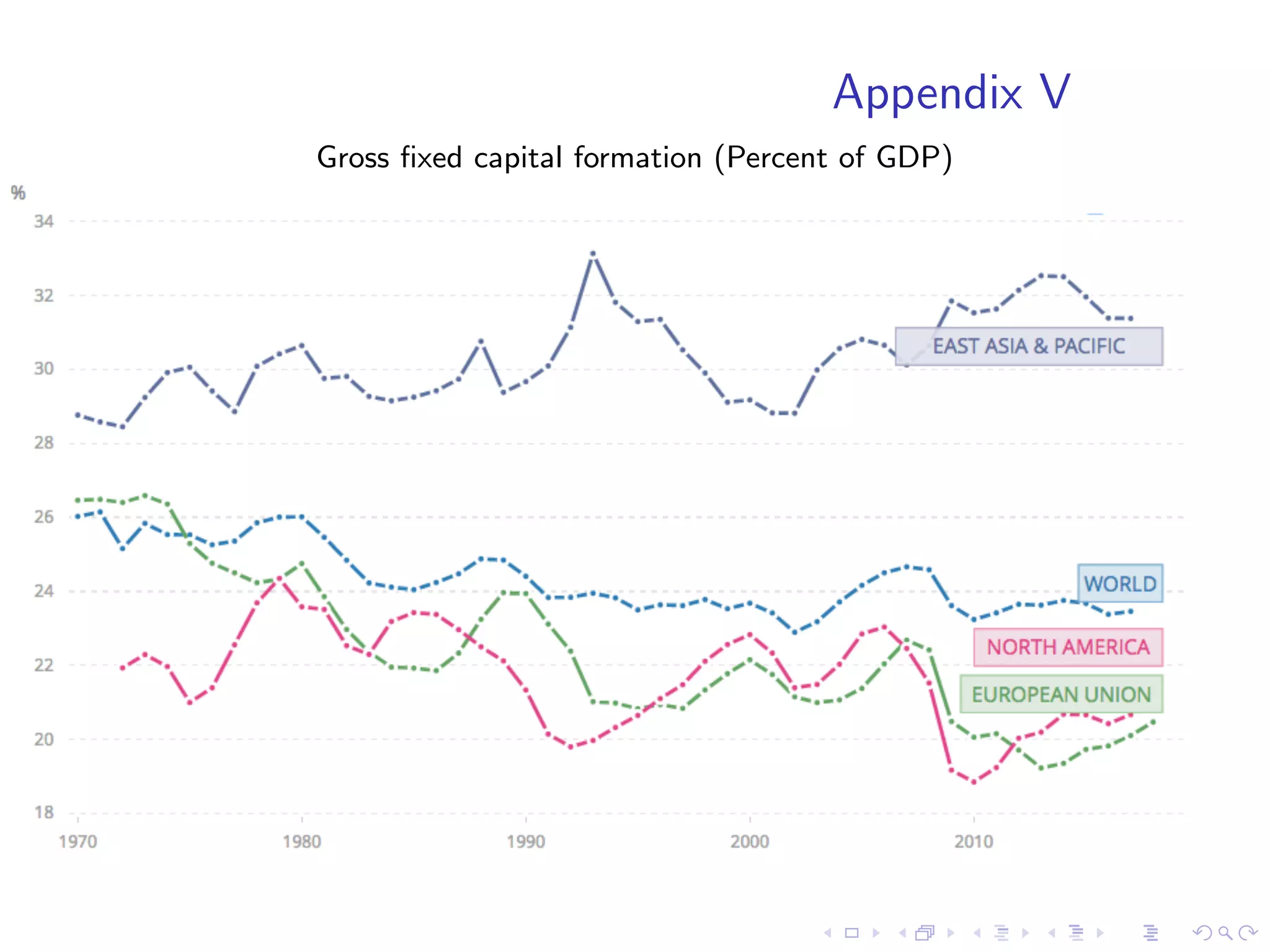

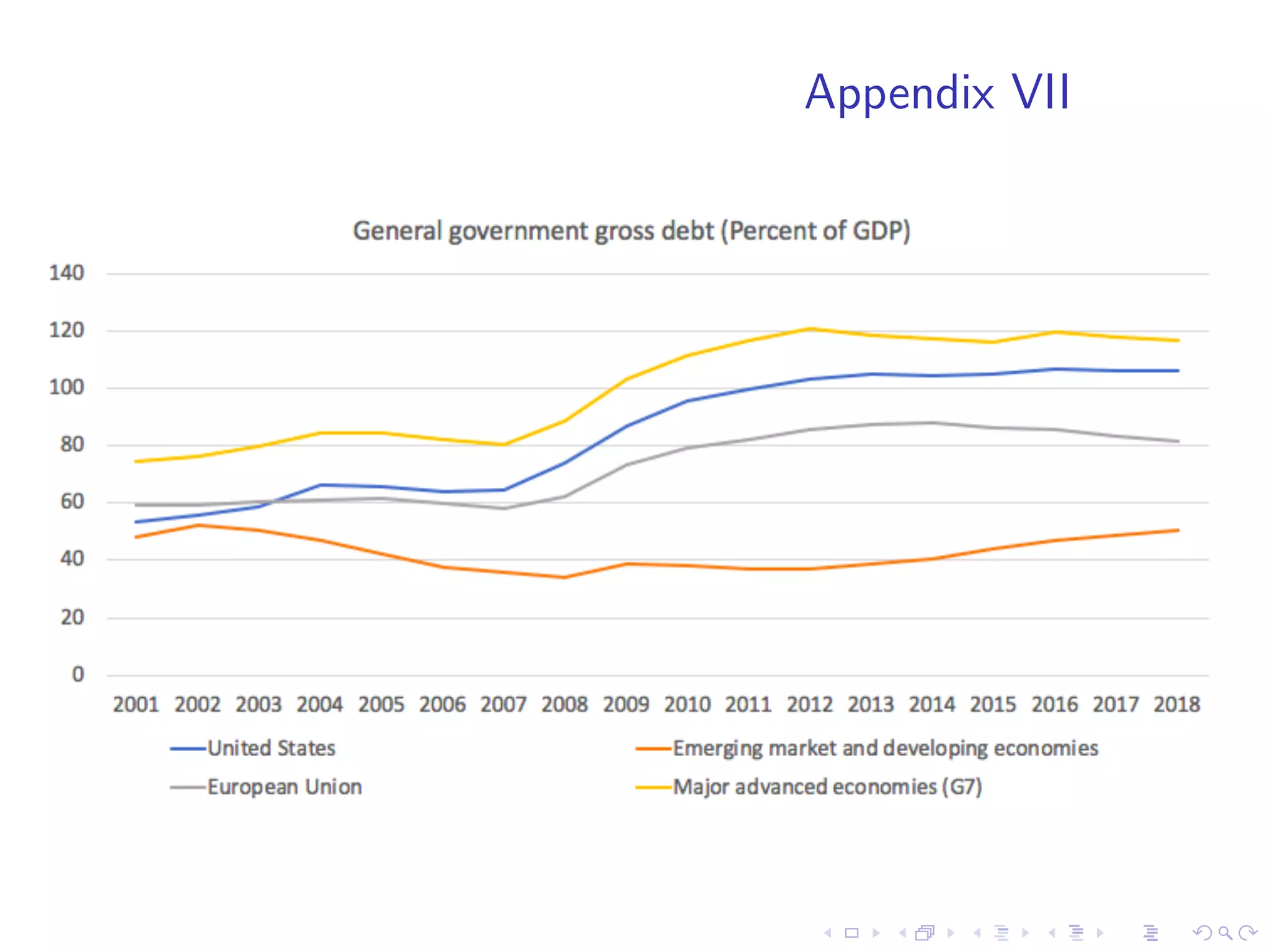

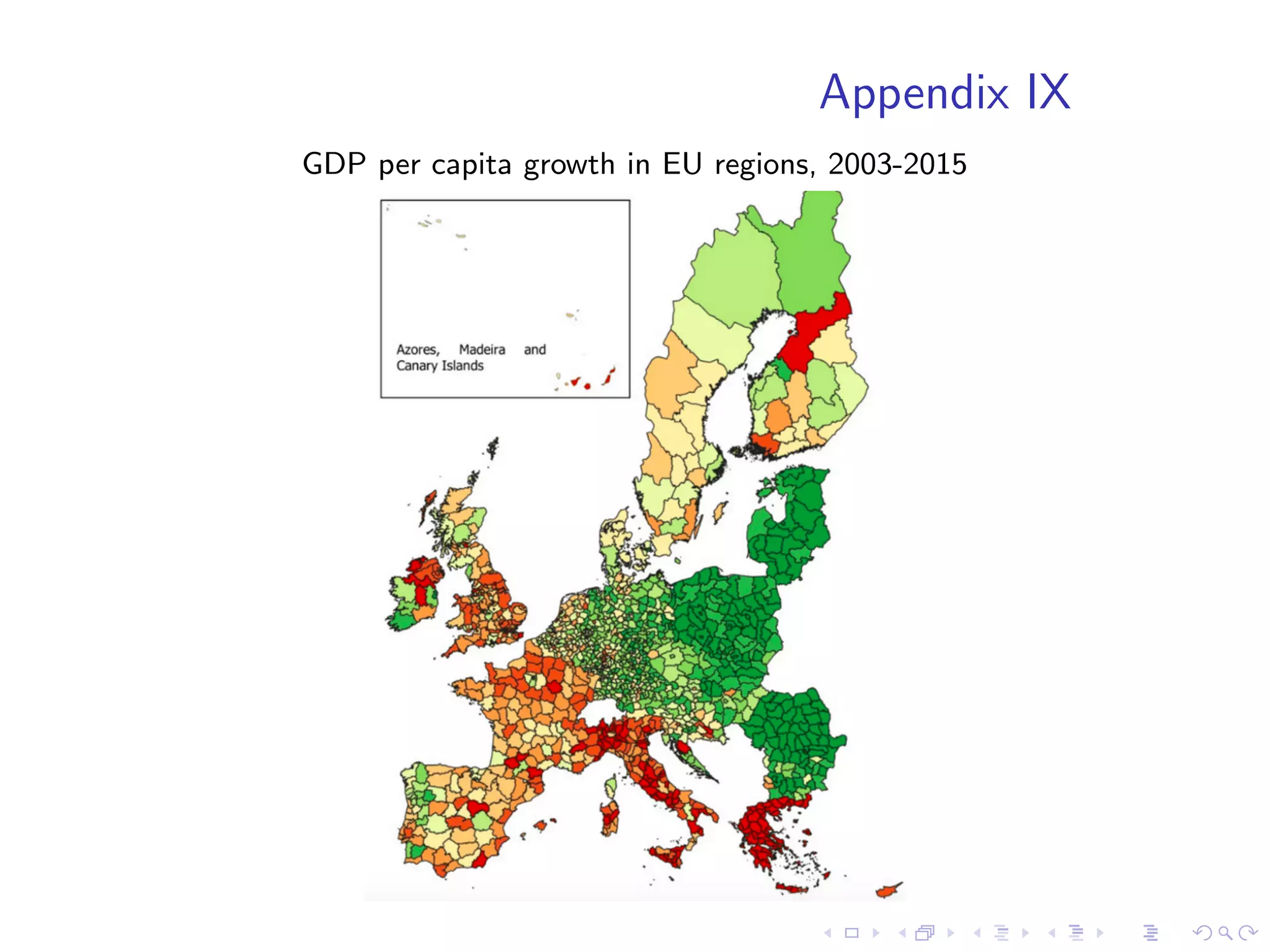

The document discusses the interplay between economic cohesion, fiscal austerity, and growth within the EU, highlighting the mechanisms of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) and its implications for member states. It outlines the history and rules governing EU fiscal policy, particularly around maintaining budget deficits below 3% of GDP, and examines the effects of fiscal policy on economic output and growth. The author argues that economic policy mistakes can lead to long-lasting consequences, emphasizing the need for clarity regarding economic cohesion and policy objectives.