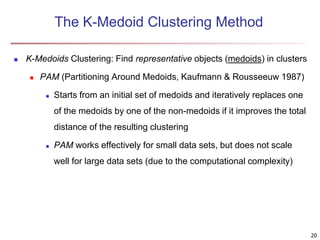

Cluster analysis is an unsupervised machine learning technique used to group unlabeled data points into clusters based on similarities. It involves finding groups of objects such that objects within a cluster are more similar to each other than objects in different clusters. The key goals of cluster analysis are to maximize intra-cluster similarity while minimizing inter-cluster similarity. Common applications of cluster analysis include market segmentation, document classification, and identifying homogeneous groups in biological data.