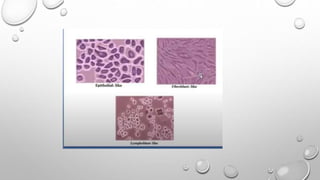

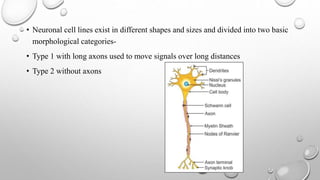

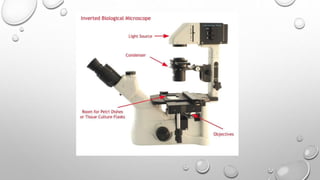

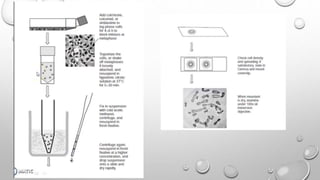

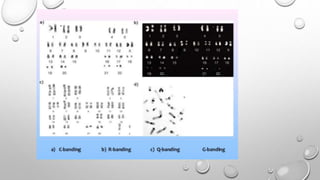

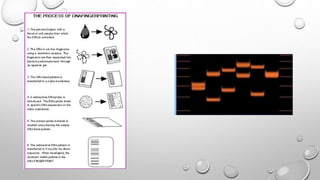

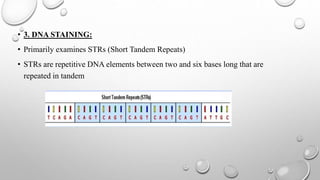

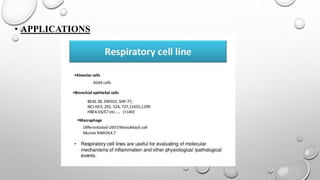

The document discusses the characterization of cell lines, detailing their definition, importance, and methods of authentication including DNA profiling and various analysis techniques. It highlights applications in scientific research such as vaccine production and drug testing, and outlines specific methods for characterization like microscopy, karyotyping, and DNA analysis. Ultimately, it emphasizes the significance of accurately identifying and maintaining the integrity of cell lines in research.