Chapter 3 discusses standardized tests used for infants and young children, their design, and selection criteria. It explores types of tests, such as ability, achievement, and aptitude tests, highlighting specific examples like the Bayley Scales and the Apgar Scale, as well as issues related to test validity and reliability. The chapter also emphasizes the importance of accurate assessment tools for evaluating development and diagnosing potential delays in early childhood.

![3.2 Steps in Standardized Test Design

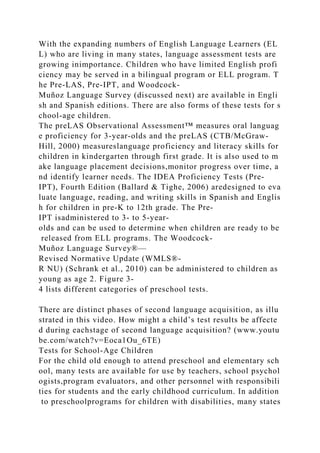

Test designers follow a series of steps when constructing a new

test. These steps ensure that the test achieves its goals and purp

oses. Inplanning a test, the developers first specify the purpose

of the test. Next, they determine the test format. As actual test d

esign begins, theyformulate objectives; write, try out, and analy

ze test items; and assemble the final test form. After the final te

st form is administered, thedevelopers establish norms and deter

mine the validity and reliability of the test. As a final step, they

develop a test manual containingprocedures for administering t

he test and statistical information on standardization results.

Specifying the Purpose of the Test

Every standardized test should have a clearly defined purpose.

The description of the test’s purpose is the framework for the co

nstructionof the test. It also allows evaluation of the instrument

when design and construction steps are completed. The Standard

s for Educational andPsychological Testing (American Psycholo

gical Association [APA], 1999) has established guidelines for in

cluding the test’s purpose in thetest manual. In 2013 the standar

ds were under revision. The 1999 standards are as follows:

B2. The test manual should state explicitly the purpose and appl

ications for which the test is recommended.

B3. The test manual should describe clearly the psychological, e

ducational and other reasoning underlying the test and the natur

eof the characteristic it is intended to measure. (p. 15)

Test designers should be able to explain what construct or chara](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter3howstandardizedtestsareuseddesignedandselected-221025182001-b13de8a7/85/CHAPTER-3-How-Standardized-Tests-Are-Used-Designed-and-Selected-docx-17-320.jpg)