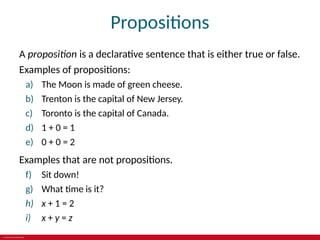

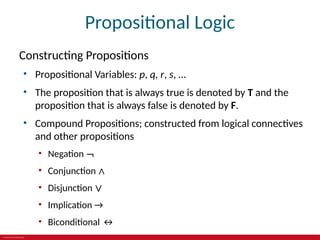

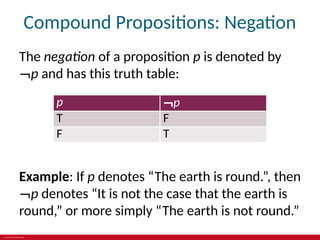

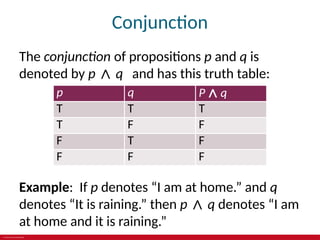

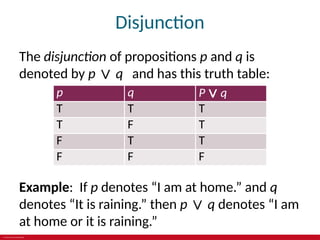

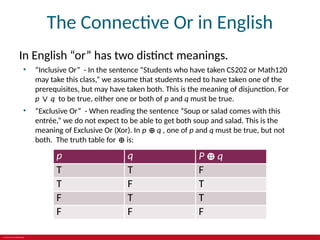

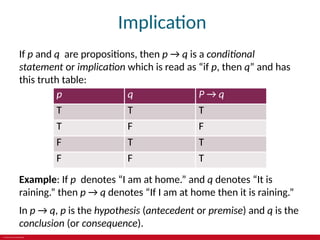

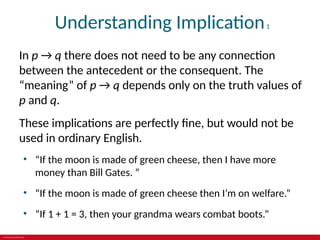

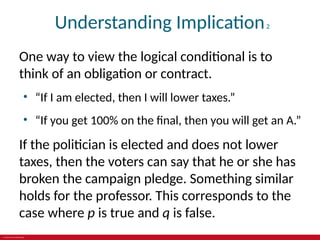

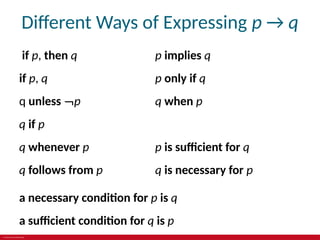

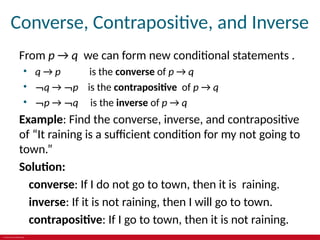

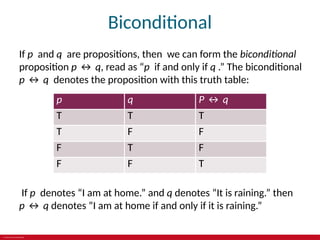

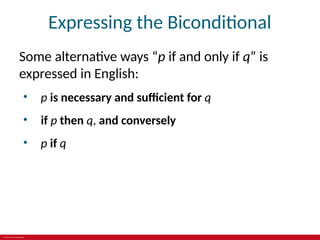

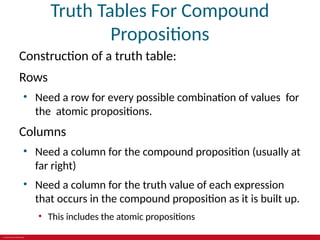

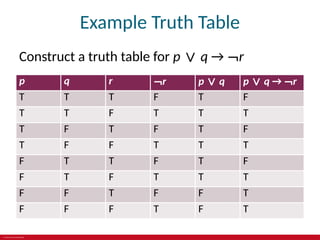

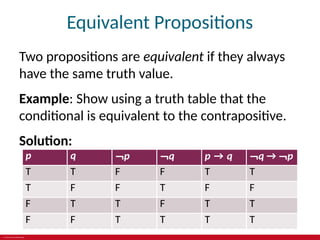

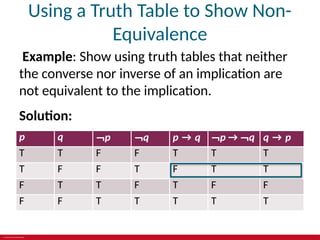

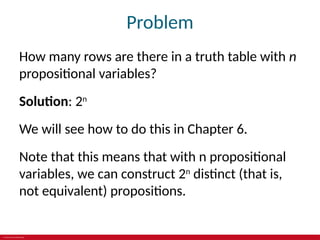

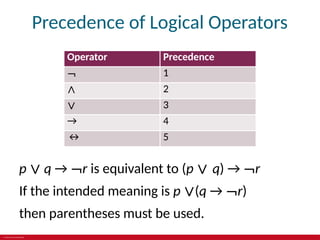

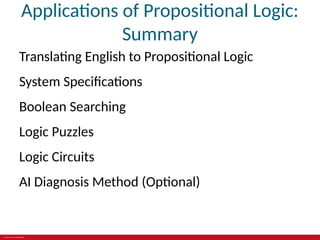

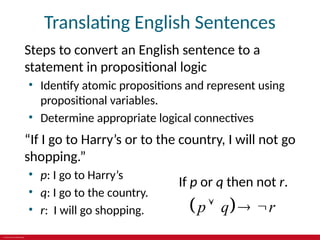

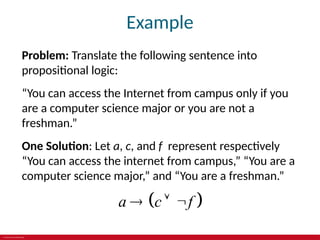

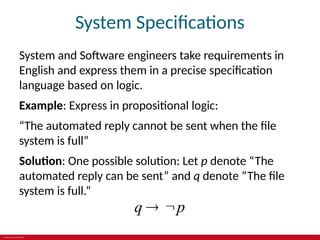

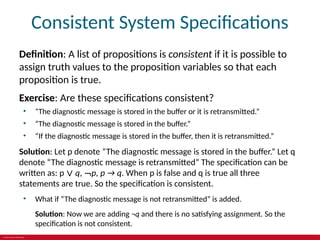

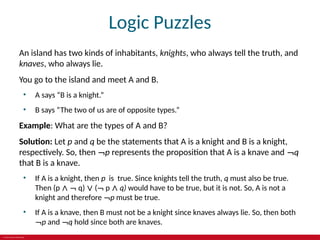

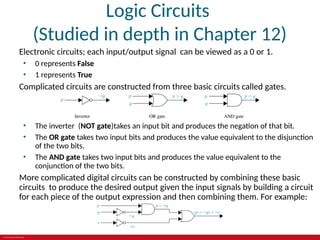

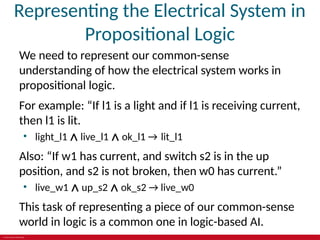

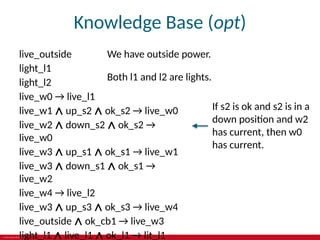

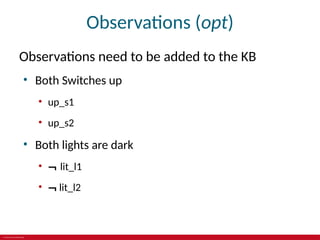

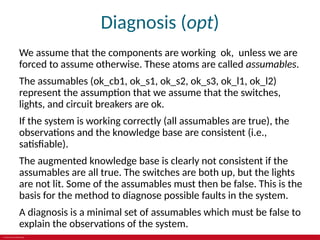

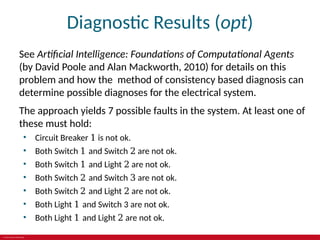

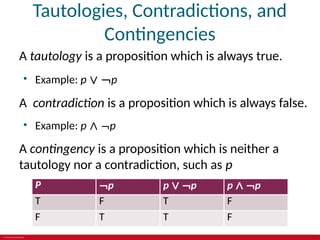

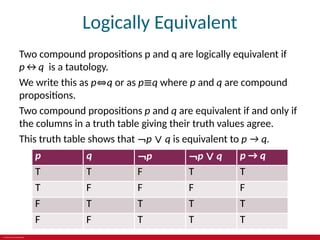

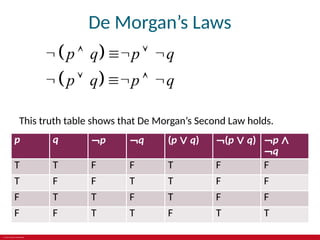

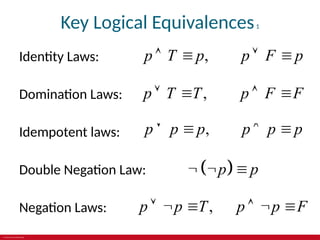

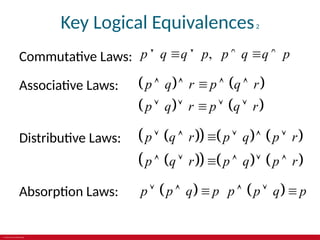

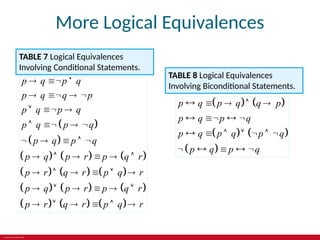

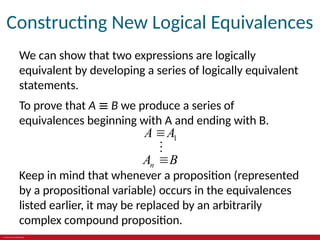

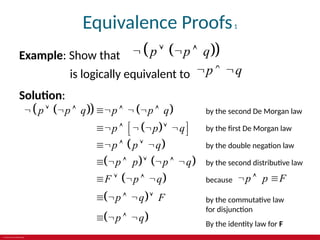

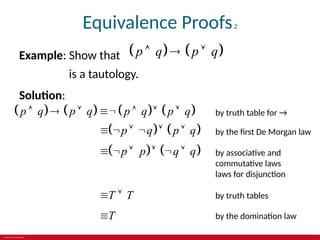

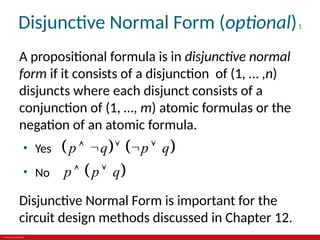

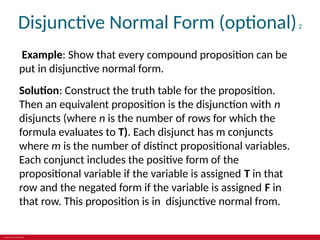

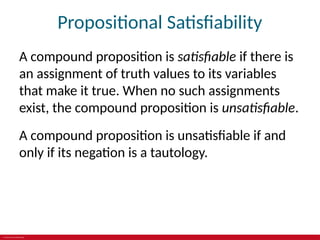

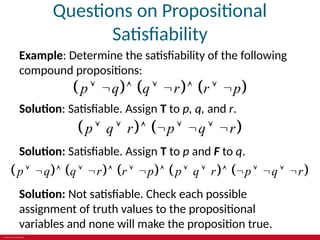

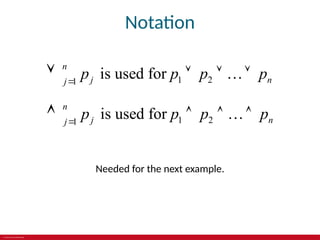

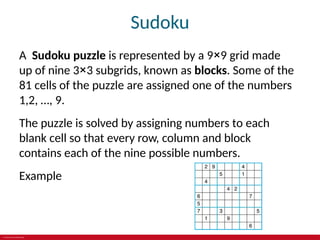

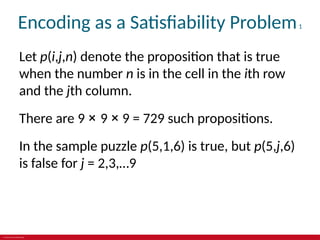

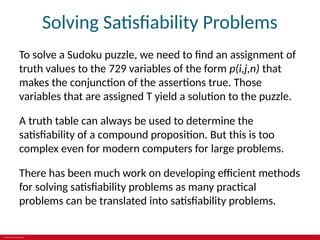

The document provides an overview of propositional logic, including definitions, truth tables, and logical connectives such as negation, conjunction, and disjunction. It explains applications of logic in translating English sentences, system specifications, logic puzzles, and electronic circuits. Additionally, it discusses the equivalence of propositions and the implications of logical statements.